Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage

Plans through your employer

Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

Learn

Looking for Medicare coverage?

Adult Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

General Information About Adult Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL)

The non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) are a heterogeneous group of lymphoproliferative malignancies with differing patterns of behavior and responses to treatment.[

Like Hodgkin lymphoma, NHL usually originates in lymphoid tissues and can spread to other organs. NHL, however, is much less predictable than Hodgkin lymphoma and has a far greater predilection to disseminate to extranodal sites. The prognosis depends on the histologic type, stage, and treatment.

Incidence and Mortality

Estimated new cases and deaths from NHL in the United States in 2022:[

- New cases: 80,470.

- Deaths: 20,250.

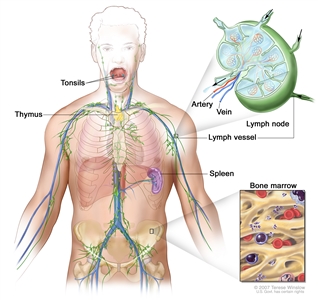

Anatomy

NHL usually originates in lymphoid tissues.

Anatomy of the lymph system.

Prognosis and Survival

NHL can be divided into two prognostic groups: the indolent lymphomas and the aggressive lymphomas.

Indolent NHL types have a relatively good prognosis with a median survival as long as 20 years, but they usually are not curable in advanced clinical stages.[

The aggressive type of NHL has a shorter natural history, but a significant number of these patients can be cured with intensive combination chemotherapy regimens.

In general, with modern treatment of patients with NHL, the overall survival rate at 5 years is over 60%. Of patients with aggressive NHL, more than 50% can be cured. Most relapses occur in the first 2 years after therapy. The risk of late relapse is higher in patients who manifest both indolent and aggressive histologies.[

While indolent NHL is responsive to immunotherapy, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, a continuous rate of relapse is usually seen in advanced stages. Patients, however, can often be re-treated with considerable success if the disease histology remains low grade. Patients who present with or convert to aggressive forms of NHL may have sustained complete remissions with combination chemotherapy regimens or aggressive consolidation with marrow or stem cell support.[

References:

- Shankland KR, Armitage JO, Hancock BW: Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Lancet 380 (9844): 848-57, 2012.

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2022. American Cancer Society, 2022. Available online. Last accessed May 25, 2022.

- Tan D, Horning SJ, Hoppe RT, et al.: Improvements in observed and relative survival in follicular grade 1-2 lymphoma during 4 decades: the Stanford University experience. Blood 122 (6): 981-7, 2013.

- Cabanillas F, Velasquez WS, Hagemeister FB, et al.: Clinical, biologic, and histologic features of late relapses in diffuse large cell lymphoma. Blood 79 (4): 1024-8, 1992.

- Bastion Y, Sebban C, Berger F, et al.: Incidence, predictive factors, and outcome of lymphoma transformation in follicular lymphoma patients. J Clin Oncol 15 (4): 1587-94, 1997.

- Yuen AR, Kamel OW, Halpern J, et al.: Long-term survival after histologic transformation of low-grade follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 13 (7): 1726-33, 1995.

Late Effects of Treatment of Adult NHL

Late effects of treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) have been observed. Impaired fertility may occur after exposure to alkylating agents.[

- Lung cancer.

- Brain cancer.

- Kidney cancer.

- Bladder cancer.

- Melanoma.

- Hodgkin lymphoma.

- Acute nonlymphocytic leukemia.

Left ventricular dysfunction was a significant late effect in long-term survivors of high-grade NHL who received more than 200 mg/m² of doxorubicin.[

Myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myelogenous leukemia are late complications of myeloablative therapy with autologous bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell support, as well as conventional chemotherapy-containing alkylating agents.[

Successful pregnancies with children born free of congenital abnormalities have been reported in young women after autologous BMT.[

Long-term impaired immune health was evaluated in a retrospective cohort study of 21,690 survivors of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma from the California Cancer Registry. Elevated incidence rate ratios were found up to 10 years later for pneumonia (10.8-fold), meningitis (5.3-fold), immunoglobulin deficiency (17.6-fold), and autoimmune cytopenias (12-fold).[

Some patients have osteopenia or osteoporosis at the start of therapy; bone density may worsen after therapy for lymphoma.[

References:

- Haddy TB, Adde MA, McCalla J, et al.: Late effects in long-term survivors of high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. J Clin Oncol 16 (6): 2070-9, 1998.

- Travis LB, Curtis RE, Glimelius B, et al.: Second cancers among long-term survivors of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 85 (23): 1932-7, 1993.

- Mudie NY, Swerdlow AJ, Higgins CD, et al.: Risk of second malignancy after non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a British Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol 24 (10): 1568-74, 2006.

- Hemminki K, Lenner P, Sundquist J, et al.: Risk of subsequent solid tumors after non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: effect of diagnostic age and time since diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 26 (11): 1850-7, 2008.

- Major A, Smith DE, Ghosh D, et al.: Risk and subtypes of secondary primary malignancies in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma survivors change over time based on stage at diagnosis. Cancer 126 (1): 189-201, 2020.

- Moser EC, Noordijk EM, van Leeuwen FE, et al.: Long-term risk of cardiovascular disease after treatment for aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 107 (7): 2912-9, 2006.

- Darrington DL, Vose JM, Anderson JR, et al.: Incidence and characterization of secondary myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myelogenous leukemia following high-dose chemoradiotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation for lymphoid malignancies. J Clin Oncol 12 (12): 2527-34, 1994.

- Stone RM, Neuberg D, Soiffer R, et al.: Myelodysplastic syndrome as a late complication following autologous bone marrow transplantation for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 12 (12): 2535-42, 1994.

- Armitage JO, Carbone PP, Connors JM, et al.: Treatment-related myelodysplasia and acute leukemia in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma patients. J Clin Oncol 21 (5): 897-906, 2003.

- André M, Mounier N, Leleu X, et al.: Second cancers and late toxicities after treatment of aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma with the ACVBP regimen: a GELA cohort study on 2837 patients. Blood 103 (4): 1222-8, 2004.

- Oddou S, Vey N, Viens P, et al.: Second neoplasms following high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation for malignant lymphomas: a report of six cases in a cohort of 171 patients from a single institution. Leuk Lymphoma 31 (1-2): 187-94, 1998.

- Lenz G, Dreyling M, Schiegnitz E, et al.: Moderate increase of secondary hematologic malignancies after myeloablative radiochemotherapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with indolent lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol 22 (24): 4926-33, 2004.

- McLaughlin P, Estey E, Glassman A, et al.: Myelodysplasia and acute myeloid leukemia following therapy for indolent lymphoma with fludarabine, mitoxantrone, and dexamethasone (FND) plus rituximab and interferon alpha. Blood 105 (12): 4573-5, 2005.

- Morton LM, Curtis RE, Linet MS, et al.: Second malignancy risks after non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia: differences by lymphoma subtype. J Clin Oncol 28 (33): 4935-44, 2010.

- Mach-Pascual S, Legare RD, Lu D, et al.: Predictive value of clonality assays in patients with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma undergoing autologous bone marrow transplant: a single institution study. Blood 91 (12): 4496-503, 1998.

- Lillington DM, Micallef IN, Carpenter E, et al.: Detection of chromosome abnormalities pre-high-dose treatment in patients developing therapy-related myelodysplasia and secondary acute myelogenous leukemia after treatment for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 19 (9): 2472-81, 2001.

- Brown JR, Yeckes H, Friedberg JW, et al.: Increasing incidence of late second malignancies after conditioning with cyclophosphamide and total-body irradiation and autologous bone marrow transplantation for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 23 (10): 2208-14, 2005.

- Jackson GH, Wood A, Taylor PR, et al.: Early high dose chemotherapy intensification with autologous bone marrow transplantation in lymphoma associated with retention of fertility and normal pregnancies in females. Scotland and Newcastle Lymphoma Group, UK. Leuk Lymphoma 28 (1-2): 127-32, 1997.

- Gangaraju R, Chen Y, Hageman L, et al.: Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma surviving blood or marrow transplantation. Cancer 125 (24): 4498-4508, 2019.

- Shree T, Li Q, Glaser SL, et al.: Impaired Immune Health in Survivors of Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 38 (15): 1664-1675, 2020.

- Ghione P, Gu JJ, Attwood K, et al.: Impaired humoral responses to COVID-19 vaccination in patients with lymphoma receiving B-cell-directed therapies. Blood 138 (9): 811-814, 2021.

- Terpos E, Trougakos IP, Gavriatopoulou M, et al.: Low neutralizing antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2 in older patients with myeloma after the first BNT162b2 vaccine dose. Blood 137 (26): 3674-3676, 2021.

- Westin JR, Thompson MA, Cataldo VD, et al.: Zoledronic acid for prevention of bone loss in patients receiving primary therapy for lymphomas: a prospective, randomized controlled phase III trial. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 13 (2): 99-105, 2013.

Cellular Classification of Adult NHL

A pathologist should be considered for consultation before a biopsy because some studies require special preparation of tissue (e.g., frozen tissue). Knowledge of cell surface markers and immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene rearrangements may help with diagnostic and therapeutic decisions. The clonal excess of light-chain immunoglobulin may differentiate malignant from reactive cells. Since the prognosis and the approach to treatment are influenced by histopathology, outside biopsy specimens should be carefully reviewed by a hematopathologist who is experienced in diagnosing lymphomas. Although lymph node biopsies are recommended whenever possible, sometimes immunophenotypic data are sufficient to allow diagnosis of lymphoma when fine-needle aspiration cytology is preferred.[

Historical Classification Systems

Historically, uniform treatment of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) has been hampered by the lack of a uniform classification system. In 1982, results of a consensus study were published as the Working Formulation.[

| Working Formulation[ |

Rappaport Classification |

|---|---|

| Low grade | |

| A. Small lymphocytic, consistent with chronic lymphocytic leukemia | Diffuse lymphocytic, well-differentiated |

| B. Follicular, predominantly small-cleaved cell | Nodular lymphocytic, poorly differentiated |

| C. Follicular, mixed small-cleaved, and large cell | Nodular mixed, lymphocytic, and histiocytic |

| Intermediate grade | |

| D. Follicular, predominantly large cell | Nodular histiocytic |

| E. Diffuse, small-cleaved cell | Diffuse lymphocytic, poorly differentiated |

| F. Diffuse mixed, small and large cell | Diffuse mixed, lymphocytic, and histiocytic |

| G. Diffuse, large cell, cleaved, or noncleaved cell | Diffuse histiocytic |

| High grade | |

| H. Immunoblastic, large cell | Diffuse histiocytic |

| I. Lymphoblastic, convoluted, or nonconvoluted cell | Diffuse lymphoblastic |

| J. Small noncleaved-cell, Burkitt, or non-Burkitt | Diffuse undifferentiated Burkitt or non-Burkitt |

Current Classification Systems

As the understanding of NHL has improved and as the histopathologic diagnosis of NHL has become more sophisticated with the use of immunologic and genetic techniques, a number of new pathologic entities have been described.[

The WHO modification of the REAL classification recognizes three major categories of lymphoid malignancies based on morphology and cell lineage: B-cell neoplasms, T-cell/natural killer (NK)-cell neoplasms, and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). Both lymphomas and lymphoid leukemias are included in this classification because both solid and circulating phases are present in many lymphoid neoplasms and distinction between them is artificial. For example, B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and B-cell small lymphocytic lymphoma are simply different manifestations of the same neoplasm, as are lymphoblastic lymphomas and acute lymphocytic leukemias. Within the B-cell and T-cell categories, two subdivisions are recognized: precursor neoplasms, which correspond to the earliest stages of differentiation, and more mature differentiated neoplasms.[

Updated REAL/WHO classification

B-cell neoplasms

- Precursor B-cell neoplasm: precursor B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL).

- Peripheral B-cell neoplasms.

- B-cell CLL/small lymphocytic lymphoma.

- B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia.

- Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma/immunocytoma.

- Mantle cell lymphoma.

- Follicular lymphoma.

- Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue (MALT) type.

- Nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (± monocytoid B-cells).

- Splenic marginal zone lymphoma (± villous lymphocytes).

- Hairy cell leukemia.

- Plasmacytoma/plasma cell myeloma.

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

- Burkitt lymphoma.

T-cell and putative NK-cell neoplasms

- Precursor T-cell neoplasm: precursor T-acute lymphoblastic leukemia/LBL.

- Peripheral T-cell and NK-cell neoplasms.

- T-cell CLL/prolymphocytic leukemia.

- T-cell granular lymphocytic leukemia.

- Mycosis fungoides (including Sézary syndrome).

- Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise characterized.

- Hepatosplenic gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma.

- Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma.

- Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma.

- Extranodal T-/NK-cell lymphoma, nasal type.

- Enteropathy-type intestinal T-cell lymphoma.

- Adult T-cell lymphoma/leukemia (human T-lymphotrophic virus [HTLV] 1+).

- Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, primary systemic type.

- Anaplastic large cell lymphoma, primary cutaneous type.

- Aggressive NK-cell leukemia.

HL

- Nodular lymphocyte-predominant HL.

- Classical HL.

- Nodular sclerosis HL.

- Lymphocyte-rich classical HL.

- Mixed-cellularity HL.

- Lymphocyte-depleted HL.

The REAL classification encompasses all the lymphoproliferative neoplasms. For more information, see the following PDQ summaries:

- Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment

- Adult Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment

- AIDS-Related Lymphoma Treatment

- Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Treatment

- Hairy Cell Leukemia Treatment

- Mycosis Fungoides (Including Sézary Syndrome) Treatment

- Plasma Cell Neoplasms (Including Multiple Myeloma) Treatment

- Primary CNS Lymphoma Treatment

PDQ modification of REAL classification of lymphoproliferative diseases

- Plasma cell disorders. For more information, see Plasma Cell Neoplasms (Including Multiple Myeloma) Treatment.

- Bone.

- Extramedullary.

- Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance.

- Plasmacytoma.

- Multiple myeloma.

- Amyloidosis.

- HL. For more information, see Adult Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment.

- Nodular sclerosis HL.

- Lymphocyte-rich classical HL.

- Mixed-cellularity HL.

- Lymphocyte-depleted HL.

- Indolent lymphoma/leukemia.

- Follicular lymphoma (follicular small-cleaved cell [grade 1], follicular mixed small-cleaved, and large cell [grade 2], and diffuse, small-cleaved cell).

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma. For more information, see Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Treatment.

- Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (Waldenström macroglobulinemia).

- Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (MALT lymphoma).

- Nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (monocytoid B-cell lymphoma).

- Splenic marginal zone lymphoma (splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes).

- Hairy cell leukemia. For more information, see Hairy Cell Leukemia Treatment.

- Mycosis fungoides (including Sézary syndrome). For more information, see Mycosis Fungoides (Including Sézary Syndrome) Treatment.

- T-cell granular lymphocytic leukemia. For more information, see Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Treatment.

- Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma/lymphomatoid papulosis (CD30-positive).

- Nodular lymphocyte–predominant Hodgkin lymphoma. For more information, see Adult Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment.

- Aggressive lymphoma/leukemia.

- Diffuse large cell lymphoma (includes diffuse mixed-cell, diffuse large cell, immunoblastic, and T-cell rich large B-cell lymphoma).

Distinguish:

- Mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma.

- Follicular large cell lymphoma (grade 3).

- Anaplastic large cell lymphoma (CD30-positive).

- Extranodal NK-/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type/aggressive NK-cell leukemia/blastic NK-cell lymphoma.

- Lymphomatoid granulomatosis (angiocentric pulmonary B-cell lymphoma).

- Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma.

- Peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified.

- Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma.

- Hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma.

- Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma.

- Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma.

- Burkitt lymphoma/Burkitt cell leukemia/Burkitt-like lymphoma.

- Precursor B-cell or T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia. For more information, see Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Treatment.

- Primary central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma. For more information, see Primary CNS Lymphoma Treatment.

- Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (HTLV 1+).

- Mantle cell lymphoma.

- Posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder.

- AIDS-related lymphoma. For more information, see AIDS-Related Lymphoma Treatment.

- True histiocytic lymphoma.

- Primary effusion lymphoma.

- B-cell or T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. For more information, see Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Treatment.

- Plasmablastic lymphoma.

- Diffuse large cell lymphoma (includes diffuse mixed-cell, diffuse large cell, immunoblastic, and T-cell rich large B-cell lymphoma).

References:

- Zeppa P, Marino G, Troncone G, et al.: Fine-needle cytology and flow cytometry immunophenotyping and subclassification of non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a critical review of 307 cases with technical suggestions. Cancer 102 (1): 55-65, 2004.

- Young NA, Al-Saleem T: Diagnosis of lymphoma by fine-needle aspiration cytology using the revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Cancer 87 (6): 325-45, 1999.

- National Cancer Institute sponsored study of classifications of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: summary and description of a working formulation for clinical usage. The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Pathologic Classification Project. Cancer 49 (10): 2112-35, 1982.

- Pugh WC: Is the working formulation adequate for the classification of the low grade lymphomas? Leuk Lymphoma 10 (Suppl 1): 1-8, 1993.

- Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, et al.: A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood 84 (5): 1361-92, 1994.

- Pittaluga S, Bijnens L, Teodorovic I, et al.: Clinical analysis of 670 cases in two trials of the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Lymphoma Cooperative Group subtyped according to the Revised European-American Classification of Lymphoid Neoplasms: a comparison with the Working Formulation. Blood 87 (10): 4358-67, 1996.

- Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD: New approach to classifying non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: clinical features of the major histologic subtypes. Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project. J Clin Oncol 16 (8): 2780-95, 1998.

- A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project. Blood 89 (11): 3909-18, 1997.

- Pileri SA, Milani M, Fraternali-Orcioni G, et al.: From the R.E.A.L. Classification to the upcoming WHO scheme: a step toward universal categorization of lymphoma entities? Ann Oncol 9 (6): 607-12, 1998.

- Society for Hematopathology Program: Society for Hematopathology Program. Am J Surg Pathol 21 (1): 114-121, 1997.

Indolent NHL

Indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) includes the following subtypes:

- Follicular lymphoma.

- Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (Waldenström macroglobulinemia).

- Marginal zone lymphoma.

- Splenic marginal zone lymphoma.

- Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

Follicular Lymphoma

Follicular lymphoma comprises 20% of all NHL and as many as 70% of the indolent lymphomas reported in American and European clinical trials.[

Prognosis

Despite the advanced stage, the median survival ranges from 8 to 15 years, leading to the designation of being indolent.[

- Age (≤60 years vs. >60 years).

- Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (normal vs. elevated).

- Stage (stage I or stage II vs. stage III or stage IV).

- Hemoglobin level (≥120 g/L vs. <120 g/L).

- Number of nodal areas (≤4 vs. >4).

Patients with one risk factor or none have an 85% 10-year survival rate, and three or more risk factors confer a 40% 10-year survival rate.[

Two retrospective analyses identified a high-risk group that had a 50% OS rate at 5 years when relapse occurred after induction chemoimmunotherapy at 24 or 30 months; this has not been validated in prospective studies or an independent cohort.[

Follicular, small-cleaved cell lymphoma and follicular mixed small-cleaved and large cell lymphoma do not have reproducibly different disease-free survival or OS.

Therapeutic approaches

Because of the often-indolent clinical course and the lack of symptoms in some patients with follicular lymphoma, watchful waiting remains a standard of care during the initial encounter and for patients with slow asymptomatic relapsing disease. When therapy is required, numerous therapeutic options may be employed in varying sequences with an OS equivalence at 5 to 10 years.[

Follicular lymphoma in situ and primary follicular lymphoma of the duodenum are particularly indolent variants that rarely progress and rarely require therapy.[

Patients with indolent lymphoma may experience a relapse with a more aggressive histology. If the clinical pattern of relapse suggests that the disease is behaving in a more aggressive manner, a biopsy can be performed, if feasible.[

In a prospective nonrandomized study, at a median follow-up of 6.8 years, 379 (14%) of 2,652 patients subsequently transformed to a more aggressive histology after an initial diagnosis of follicular lymphoma.[

Lymphoplasmacytic Lymphoma (Waldenström Macroglobulinemia)

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma is usually associated with a monoclonal serum paraprotein of immunoglobulin M (IgM) type (Waldenström macroglobulinemia).[

Asymptomatic patients can be monitored for evidence of disease progression without immediate need for chemotherapy.[

Prognostic factors associated with symptoms requiring therapy include the following:

- Age 70 years or older.

- Beta-2-microglobulin of 3 mg/dL or more.

- Increased serum LDH.[

40 ]

Therapeutic approaches

The management of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma is similar to that of other low-grade lymphomas, especially diffuse, small lymphocytic lymphoma/chronic lymphocytic leukemia.[

First-line regimens include rituximab and ibrutinib (a Bruton tyrosine kinase [BTK] inhibitor), rituximab alone, the nucleoside analogs, and alkylating agents, either as single agents or as part of combination chemotherapy.[

Previously untreated patients who received rituximab had response rates of 60% to 80%, but close monitoring of the serum IgM is required because of a sudden rise in this paraprotein at the start of therapy.[

Myeloablative therapy with autologous or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell support is under clinical evaluation.[

Marginal Zone Lymphoma

Marginal zone lymphomas were previously included among the diffuse, small lymphocytic lymphomas. When marginal zone lymphomas involve the nodes, they are called monocytoid B-cell lymphomas or nodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas, and when they involve extranodal sites (e.g., gastrointestinal tract, thyroid, lung, breast, orbit, and skin), they are called mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue (MALT) lymphomas.[

Gastric MALT

Many patients have a history of autoimmune disease, such as Hashimoto thyroiditis or Sjögren syndrome, or of Helicobacter gastritis. Most patients present with stage I or stage II extranodal disease, which is most often in the stomach. Treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection may resolve most cases of localized gastric involvement.[

Extragastric MALT

Localized involvement of other sites can be treated with radiation or surgery.[

Nodal marginal zone lymphoma

Patients with nodal marginal zone lymphoma (monocytoid B-cell lymphoma) are treated with the same paradigm of watchful waiting or therapies as described for follicular lymphoma.[

Mediterranean abdominal lymphoma

The disease variously known as Mediterranean abdominal lymphoma, heavy–chain disease, or immunoproliferative small intestinal disease (IPSID), which occurs in young adults in eastern Mediterranean countries, is another version of MALT lymphoma, which responds to antibiotics in its early stages.[

Splenic marginal zone lymphoma

Splenic marginal zone lymphoma is an indolent lymphoma that is marked by massive splenomegaly and peripheral blood and bone marrow involvement, usually without adenopathy.[

Management is similar to that of other low-grade lymphomas and usually involves rituximab alone or rituximab in combination with purine analogs or alkylating agent chemotherapy.[

Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma presents in the skin only with no pre-existing lymphoproliferative disease and no extracutaneous sites of involvement.[

Patients with localized disease usually undergo radiation therapy. With more disseminated involvement, watchful waiting or doxorubicin-based combination chemotherapy is applied.[

For more information, see Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Treatment, Mycosis Fungoides (Including Sézary Syndrome) Treatment, Hairy Cell Leukemia Treatment, and Adult Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment.

References:

- Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD: New approach to classifying non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: clinical features of the major histologic subtypes. Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project. J Clin Oncol 16 (8): 2780-95, 1998.

- A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. The Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Classification Project. Blood 89 (11): 3909-18, 1997.

- Society for Hematopathology Program: Society for Hematopathology Program. Am J Surg Pathol 21 (1): 114-121, 1997.

- López-Guillermo A, Cabanillas F, McDonnell TI, et al.: Correlation of bcl-2 rearrangement with clinical characteristics and outcome in indolent follicular lymphoma. Blood 93 (9): 3081-7, 1999.

- Peterson BA, Petroni GR, Frizzera G, et al.: Prolonged single-agent versus combination chemotherapy in indolent follicular lymphomas: a study of the cancer and leukemia group B. J Clin Oncol 21 (1): 5-15, 2003.

- Swenson WT, Wooldridge JE, Lynch CF, et al.: Improved survival of follicular lymphoma patients in the United States. J Clin Oncol 23 (22): 5019-26, 2005.

- Liu Q, Fayad L, Cabanillas F, et al.: Improvement of overall and failure-free survival in stage IV follicular lymphoma: 25 years of treatment experience at The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center. J Clin Oncol 24 (10): 1582-9, 2006.

- Kahl BS, Yang DT: Follicular lymphoma: evolving therapeutic strategies. Blood 127 (17): 2055-63, 2016.

- Ardeshna KM, Smith P, Norton A, et al.: Long-term effect of a watch and wait policy versus immediate systemic treatment for asymptomatic advanced-stage non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 362 (9383): 516-22, 2003.

- Armitage JO, Longo DL: Is watch and wait still acceptable for patients with low-grade follicular lymphoma? Blood 127 (23): 2804-8, 2016.

- Solal-Céligny P, Roy P, Colombat P, et al.: Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood 104 (5): 1258-65, 2004.

- Perea G, Altés A, Montoto S, et al.: Prognostic indexes in follicular lymphoma: a comparison of different prognostic systems. Ann Oncol 16 (9): 1508-13, 2005.

- Buske C, Hoster E, Dreyling M, et al.: The Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) separates high-risk from intermediate- or low-risk patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma treated front-line with rituximab and the combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) with respect to treatment outcome. Blood 108 (5): 1504-8, 2006.

- Federico M, Bellei M, Marcheselli L, et al.: Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index 2: a new prognostic index for follicular lymphoma developed by the international follicular lymphoma prognostic factor project. J Clin Oncol 27 (27): 4555-62, 2009.

- Bachy E, Maurer MJ, Habermann TM, et al.: A simplified scoring system in de novo follicular lymphoma treated initially with immunochemotherapy. Blood 132 (1): 49-58, 2018.

- Casulo C, Byrtek M, Dawson KL, et al.: Early Relapse of Follicular Lymphoma After Rituximab Plus Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisone Defines Patients at High Risk for Death: An Analysis From the National LymphoCare Study. J Clin Oncol 33 (23): 2516-22, 2015.

- Shi Q, Flowers CR, Hiddemann W, et al.: Thirty-Month Complete Response as a Surrogate End Point in First-Line Follicular Lymphoma Therapy: An Individual Patient-Level Analysis of Multiple Randomized Trials. J Clin Oncol 35 (5): 552-560, 2017.

- Freeman CL, Kridel R, Moccia AA, et al.: Early progression after bendamustine-rituximab is associated with high risk of transformation in advanced stage follicular lymphoma. Blood 134 (9): 761-764, 2019.

- Brice P, Bastion Y, Lepage E, et al.: Comparison in low-tumor-burden follicular lymphomas between an initial no-treatment policy, prednimustine, or interferon alfa: a randomized study from the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires. Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. J Clin Oncol 15 (3): 1110-7, 1997.

- Young RC, Longo DL, Glatstein E, et al.: The treatment of indolent lymphomas: watchful waiting v aggressive combined modality treatment. Semin Hematol 25 (2 Suppl 2): 11-6, 1988.

- Luminari S, Ferrari A, Manni M, et al.: Long-Term Results of the FOLL05 Trial Comparing R-CVP Versus R-CHOP Versus R-FM for the Initial Treatment of Patients With Advanced-Stage Symptomatic Follicular Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 36 (7): 689-696, 2018.

- Lockmer S, Østenstad B, Hagberg H, et al.: Chemotherapy-Free Initial Treatment of Advanced Indolent Lymphoma Has Durable Effect With Low Toxicity: Results From Two Nordic Lymphoma Group Trials With More Than 10 Years of Follow-Up. J Clin Oncol : JCO1800262, 2018.

- Morschhauser F, Fowler NH, Feugier P, et al.: Rituximab plus Lenalidomide in Advanced Untreated Follicular Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 379 (10): 934-947, 2018.

- Leonard JP, Trnený M, Izutsu K, et al.: Augment: a phase III randomized study of lenalidomide Plus rituximab (R2) vs rituximab/placebo in patients with relapsed/refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma. [Abstract] Blood 132 (Suppl 1): A-445, 2018.

- Zucca E, Rondeau S, Vanazzi A, et al.: Short regimen of rituximab plus lenalidomide in follicular lymphoma patients in need of first-line therapy. Blood 134 (4): 353-362, 2019.

- Marcus R, Davies A, Ando K, et al.: Obinutuzumab for the First-Line Treatment of Follicular Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 377 (14): 1331-1344, 2017.

- Dreyling M, Santoro A, Mollica L, et al.: Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Inhibition by Copanlisib in Relapsed or Refractory Indolent Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 35 (35): 3898-3905, 2017.

- Schaaf M, Reiser M, Borchmann P, et al.: High-dose therapy with autologous stem cell transplantation versus chemotherapy or immuno-chemotherapy for follicular lymphoma in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1: CD007678, 2012.

- Schmatz AI, Streubel B, Kretschmer-Chott E, et al.: Primary follicular lymphoma of the duodenum is a distinct mucosal/submucosal variant of follicular lymphoma: a retrospective study of 63 cases. J Clin Oncol 29 (11): 1445-51, 2011.

- Jegalian AG, Eberle FC, Pack SD, et al.: Follicular lymphoma in situ: clinical implications and comparisons with partial involvement by follicular lymphoma. Blood 118 (11): 2976-84, 2011.

- Louissaint A, Ackerman AM, Dias-Santagata D, et al.: Pediatric-type nodal follicular lymphoma: an indolent clonal proliferation in children and adults with high proliferation index and no BCL2 rearrangement. Blood 120 (12): 2395-404, 2012.

- Sarkozy C, Trneny M, Xerri L, et al.: Risk Factors and Outcomes for Patients With Follicular Lymphoma Who Had Histologic Transformation After Response to First-Line Immunochemotherapy in the PRIMA Trial. J Clin Oncol 34 (22): 2575-82, 2016.

- Tsimberidou AM, O'Brien S, Khouri I, et al.: Clinical outcomes and prognostic factors in patients with Richter's syndrome treated with chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy with or without stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol 24 (15): 2343-51, 2006.

- Montoto S, Davies AJ, Matthews J, et al.: Risk and clinical implications of transformation of follicular lymphoma to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 25 (17): 2426-33, 2007.

- Villa D, Crump M, Panzarella T, et al.: Autologous and allogeneic stem-cell transplantation for transformed follicular lymphoma: a report of the Canadian blood and marrow transplant group. J Clin Oncol 31 (9): 1164-71, 2013.

- Williams CD, Harrison CN, Lister TA, et al.: High-dose therapy and autologous stem-cell support for chemosensitive transformed low-grade follicular non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a case-matched study from the European Bone Marrow Transplant Registry. J Clin Oncol 19 (3): 727-35, 2001.

- Wagner-Johnston ND, Link BK, Byrtek M, et al.: Outcomes of transformed follicular lymphoma in the modern era: a report from the National LymphoCare Study (NLCS). Blood 126 (7): 851-7, 2015.

- Leblond V, Kastritis E, Advani R, et al.: Treatment recommendations from the Eighth International Workshop on Waldenström's Macroglobulinemia. Blood 128 (10): 1321-8, 2016.

- Treon SP, Xu L, Yang G, et al.: MYD88 L265P somatic mutation in Waldenström's macroglobulinemia. N Engl J Med 367 (9): 826-33, 2012.

- Dhodapkar MV, Hoering A, Gertz MA, et al.: Long-term survival in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: 10-year follow-up of Southwest Oncology Group-directed intergroup trial S9003. Blood 113 (4): 793-6, 2009.

- Ansell SM, Kyle RA, Reeder CB, et al.: Diagnosis and management of Waldenström macroglobulinemia: Mayo stratification of macroglobulinemia and risk-adapted therapy (mSMART) guidelines. Mayo Clin Proc 85 (9): 824-33, 2010.

- Kapoor P, Ansell SM, Fonseca R, et al.: Diagnosis and Management of Waldenström Macroglobulinemia: Mayo Stratification of Macroglobulinemia and Risk-Adapted Therapy (mSMART) Guidelines 2016. JAMA Oncol 3 (9): 1257-1265, 2017.

- Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E: How I treat Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Blood 134 (23): 2022-2035, 2019.

- Gertz MA, Anagnostopoulos A, Anderson K, et al.: Treatment recommendations in Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia: consensus panel recommendations from the Second International Workshop on Waldenstrom's Macroglobulinemia. Semin Oncol 30 (2): 121-6, 2003.

- Dimopoulos MA, Anagnostopoulos A, Kyrtsonis MC, et al.: Primary treatment of Waldenström macroglobulinemia with dexamethasone, rituximab, and cyclophosphamide. J Clin Oncol 25 (22): 3344-9, 2007.

- Treon SP, Branagan AR, Ioakimidis L, et al.: Long-term outcomes to fludarabine and rituximab in Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Blood 113 (16): 3673-8, 2009.

- Leblond V, Johnson S, Chevret S, et al.: Results of a randomized trial of chlorambucil versus fludarabine for patients with untreated Waldenström macroglobulinemia, marginal zone lymphoma, or lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 31 (3): 301-7, 2013.

- Buske C, Tedeschi A, Trotman J, et al.: Ibrutinib Plus Rituximab Versus Placebo Plus Rituximab for Waldenström's Macroglobulinemia: Final Analysis From the Randomized Phase III iNNOVATE Study. J Clin Oncol 40 (1): 52-62, 2022.

- Tam CS, Opat S, D'Sa S, et al.: A randomized phase 3 trial of zanubrutinib vs ibrutinib in symptomatic Waldenström macroglobulinemia: the ASPEN study. Blood 136 (18): 2038-2050, 2020.

- Jalink M, Berentsen S, Castillo JJ, et al.: Effect of ibrutinib treatment on hemolytic anemia and acrocyanosis in cold agglutinin disease/cold agglutinin syndrome. Blood 138 (20): 2002-2005, 2021.

- Dimopoulos MA, Zervas C, Zomas A, et al.: Treatment of Waldenström's macroglobulinemia with rituximab. J Clin Oncol 20 (9): 2327-33, 2002.

- Treon SP, Branagan AR, Hunter Z, et al.: Paradoxical increases in serum IgM and viscosity levels following rituximab in Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia. Ann Oncol 15 (10): 1481-3, 2004.

- Dimopoulos MA, Chen C, Kastritis E, et al.: Bortezomib as a treatment option in patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 10 (2): 110-7, 2010.

- Gavriatopoulou M, García-Sanz R, Kastritis E, et al.: BDR in newly diagnosed patients with WM: final analysis of a phase 2 study after a minimum follow-up of 6 years. Blood 129 (4): 456-459, 2017.

- Kersten MJ, Amaador K, Minnema MC, et al.: Combining Ixazomib With Subcutaneous Rituximab and Dexamethasone in Relapsed or Refractory Waldenström's Macroglobulinemia: Final Analysis of the Phase I/II HOVON124/ECWM-R2 Study. J Clin Oncol 40 (1): 40-51, 2022.

- Treon SP, Ioakimidis L, Soumerai JD, et al.: Primary therapy of Waldenström macroglobulinemia with bortezomib, dexamethasone, and rituximab: WMCTG clinical trial 05-180. J Clin Oncol 27 (23): 3830-5, 2009.

- Dimopoulos MA, García-Sanz R, Gavriatopoulou M, et al.: Primary therapy of Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia (WM) with weekly bortezomib, low-dose dexamethasone, and rituximab (BDR): long-term results of a phase 2 study of the European Myeloma Network (EMN). Blood 122 (19): 3276-82, 2013.

- Treon SP, Tripsas CK, Meid K, et al.: Carfilzomib, rituximab, and dexamethasone (CaRD) treatment offers a neuropathy-sparing approach for treating Waldenström's macroglobulinemia. Blood 124 (4): 503-10, 2014.

- Dimopoulos MA, Alexanian R: Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia. Blood 83 (6): 1452-9, 1994.

- Laszlo D, Andreola G, Rigacci L, et al.: Rituximab and subcutaneous 2-chloro-2'-deoxyadenosine combination treatment for patients with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia: clinical and biologic results of a phase II multicenter study. J Clin Oncol 28 (13): 2233-8, 2010.

- García-Sanz R, Montoto S, Torrequebrada A, et al.: Waldenström macroglobulinaemia: presenting features and outcome in a series with 217 cases. Br J Haematol 115 (3): 575-82, 2001.

- Buske C, Hoster E, Dreyling M, et al.: The addition of rituximab to front-line therapy with CHOP (R-CHOP) results in a higher response rate and longer time to treatment failure in patients with lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma: results of a randomized trial of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). Leukemia 23 (1): 153-61, 2009.

- Ghobrial IM, Hong F, Padmanabhan S, et al.: Phase II trial of weekly bortezomib in combination with rituximab in relapsed or relapsed and refractory Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. J Clin Oncol 28 (8): 1422-8, 2010.

- Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al.: Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 381 (9873): 1203-10, 2013.

- Castillo JJ, Allan JN, Siddiqi T, et al.: Venetoclax in Previously Treated Waldenström Macroglobulinemia. J Clin Oncol 40 (1): 63-71, 2022.

- Castillo JJ, Itchaki G, Paludo J, et al.: Ibrutinib for the treatment of Bing-Neel syndrome: a multicenter study. Blood 133 (4): 299-305, 2019.

- Dreger P, Glass B, Kuse R, et al.: Myeloablative radiochemotherapy followed by reinfusion of purged autologous stem cells for Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia. Br J Haematol 106 (1): 115-8, 1999.

- Desikan R, Dhodapkar M, Siegel D, et al.: High-dose therapy with autologous haemopoietic stem cell support for Waldenström's macroglobulinaemia. Br J Haematol 105 (4): 993-6, 1999.

- Martin P, Chadburn A, Christos P, et al.: Intensive treatment strategies may not provide superior outcomes in mantle cell lymphoma: overall survival exceeding 7 years with standard therapies. Ann Oncol 19 (7): 1327-30, 2008.

- Kyriakou C, Canals C, Cornelissen JJ, et al.: Allogeneic stem-cell transplantation in patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia: report from the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. J Clin Oncol 28 (33): 4926-34, 2010.

- Leleu X, Soumerai J, Roccaro A, et al.: Increased incidence of transformation and myelodysplasia/acute leukemia in patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia treated with nucleoside analogs. J Clin Oncol 27 (2): 250-5, 2009.

- Leblond V, Lévy V, Maloisel F, et al.: Multicenter, randomized comparative trial of fludarabine and the combination of cyclophosphamide-doxorubicin-prednisone in 92 patients with Waldenström macroglobulinemia in first relapse or with primary refractory disease. Blood 98 (9): 2640-4, 2001.

- Bertoni F, Zucca E: State-of-the-art therapeutics: marginal-zone lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 23 (26): 6415-20, 2005.

- Zucca E, Bertoni F: The spectrum of MALT lymphoma at different sites: biological and therapeutic relevance. Blood 127 (17): 2082-92, 2016.

- Thieblemont C, Cascione L, Conconi A, et al.: A MALT lymphoma prognostic index. Blood 130 (12): 1409-1417, 2017.

- Alderuccio JP, Zhao W, Desai A, et al.: Risk Factors for Transformation to Higher-Grade Lymphoma and Its Impact on Survival in a Large Cohort of Patients With Marginal Zone Lymphoma From a Single Institution. J Clin Oncol : JCO1800138, 2018.

- Zullo A, Hassan C, Andriani A, et al.: Eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori in patients with gastric MALT lymphoma: a pooled data analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 104 (8): 1932-7; quiz 1938, 2009.

- Nakamura S, Sugiyama T, Matsumoto T, et al.: Long-term clinical outcome of gastric MALT lymphoma after eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a multicentre cohort follow-up study of 420 patients in Japan. Gut 61 (4): 507-13, 2012.

- Wündisch T, Thiede C, Morgner A, et al.: Long-term follow-up of gastric MALT lymphoma after Helicobacter pylori eradication. J Clin Oncol 23 (31): 8018-24, 2005.

- Ye H, Liu H, Raderer M, et al.: High incidence of t(11;18)(q21;q21) in Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric MALT lymphoma. Blood 101 (7): 2547-50, 2003.

- Lévy M, Copie-Bergman C, Gameiro C, et al.: Prognostic value of translocation t(11;18) in tumoral response of low-grade gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type to oral chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 23 (22): 5061-6, 2005.

- Nakamura S, Ye H, Bacon CM, et al.: Clinical impact of genetic aberrations in gastric MALT lymphoma: a comprehensive analysis using interphase fluorescence in situ hybridisation. Gut 56 (10): 1358-63, 2007.

- Schechter NR, Yahalom J: Low-grade MALT lymphoma of the stomach: a review of treatment options. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 46 (5): 1093-103, 2000.

- Tsang RW, Gospodarowicz MK, Pintilie M, et al.: Stage I and II MALT lymphoma: results of treatment with radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 50 (5): 1258-64, 2001.

- Tsang RW, Gospodarowicz MK, Pintilie M, et al.: Localized mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma treated with radiation therapy has excellent clinical outcome. J Clin Oncol 21 (22): 4157-64, 2003.

- Tsai HK, Li S, Ng AK, et al.: Role of radiation therapy in the treatment of stage I/II mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Ann Oncol 18 (4): 672-8, 2007.

- Martinelli G, Laszlo D, Ferreri AJ, et al.: Clinical activity of rituximab in gastric marginal zone non-Hodgkin's lymphoma resistant to or not eligible for anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy. J Clin Oncol 23 (9): 1979-83, 2005.

- Cogliatti SB, Schmid U, Schumacher U, et al.: Primary B-cell gastric lymphoma: a clinicopathological study of 145 patients. Gastroenterology 101 (5): 1159-70, 1991.

- Zinzani PL, Magagnoli M, Galieni P, et al.: Nongastrointestinal low-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: analysis of 75 patients. J Clin Oncol 17 (4): 1254, 1999.

- Thieblemont C, Bastion Y, Berger F, et al.: Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue gastrointestinal and nongastrointestinal lymphoma behavior: analysis of 108 patients. J Clin Oncol 15 (4): 1624-30, 1997.

- Pavlick AC, Gerdes H, Portlock CS: Endoscopic ultrasound in the evaluation of gastric small lymphocytic mucosa-associated lymphoid tumors. J Clin Oncol 15 (5): 1761-6, 1997.

- Morgner A, Miehlke S, Fischbach W, et al.: Complete remission of primary high-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Clin Oncol 19 (7): 2041-8, 2001.

- Chen LT, Lin JT, Shyu RY, et al.: Prospective study of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in stage I(E) high-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the stomach. J Clin Oncol 19 (22): 4245-51, 2001.

- Chen LT, Lin JT, Tai JJ, et al.: Long-term results of anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy in early-stage gastric high-grade transformed MALT lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 97 (18): 1345-53, 2005.

- Kuo SH, Yeh KH, Wu MS, et al.: Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy is effective in the treatment of early-stage H pylori-positive gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Blood 119 (21): 4838-44; quiz 5057, 2012.

- Uno T, Isobe K, Shikama N, et al.: Radiotherapy for extranodal, marginal zone, B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue originating in the ocular adnexa: a multiinstitutional, retrospective review of 50 patients. Cancer 98 (4): 865-71, 2003.

- Bayraktar S, Bayraktar UD, Stefanovic A, et al.: Primary ocular adnexal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALT): single institution experience in a large cohort of patients. Br J Haematol 152 (1): 72-80, 2011.

- Stefanovic A, Lossos IS: Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of the ocular adnexa. Blood 114 (3): 501-10, 2009.

- Vazquez A, Khan MN, Sanghvi S, et al.: Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue of the salivary glands: a population-based study from 1994 to 2009. Head Neck 37 (1): 18-22, 2015.

- Raderer M, Streubel B, Woehrer S, et al.: High relapse rate in patients with MALT lymphoma warrants lifelong follow-up. Clin Cancer Res 11 (9): 3349-52, 2005.

- Sretenovic M, Colovic M, Jankovic G, et al.: More than a third of non-gastric malt lymphomas are disseminated at diagnosis: a single center survey. Eur J Haematol 82 (5): 373-80, 2009.

- Nathwani BN, Drachenberg MR, Hernandez AM, et al.: Nodal monocytoid B-cell lymphoma (nodal marginal-zone B-cell lymphoma). Semin Hematol 36 (2): 128-38, 1999.

- Raderer M, Wöhrer S, Streubel B, et al.: Assessment of disease dissemination in gastric compared with extragastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma using extensive staging: a single-center experience. J Clin Oncol 24 (19): 3136-41, 2006.

- Zucca E, Conconi A, Martinelli G, et al.: Final Results of the IELSG-19 Randomized Trial of Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma: Improved Event-Free and Progression-Free Survival With Rituximab Plus Chlorambucil Versus Either Chlorambucil or Rituximab Monotherapy. J Clin Oncol 35 (17): 1905-1912, 2017.

- Kiesewetter B, Raderer M: Antibiotic therapy in nongastrointestinal MALT lymphoma: a review of the literature. Blood 122 (8): 1350-7, 2013.

- Grünberger B, Hauff W, Lukas J, et al.: 'Blind' antibiotic treatment targeting Chlamydia is not effective in patients with MALT lymphoma of the ocular adnexa. Ann Oncol 17 (3): 484-7, 2006.

- Kuo SH, Chen LT, Yeh KH, et al.: Nuclear expression of BCL10 or nuclear factor kappa B predicts Helicobacter pylori-independent status of early-stage, high-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas. J Clin Oncol 22 (17): 3491-7, 2004.

- Desai A, Joag MG, Lekakis L, et al.: Long-term course of patients with primary ocular adnexal MALT lymphoma: a large single-institution cohort study. Blood 129 (3): 324-332, 2017.

- Thieblemont C, Molina T, Davi F: Optimizing therapy for nodal marginal zone lymphoma. Blood 127 (17): 2064-71, 2016.

- Luminari S, Merli M, Rattotti S, et al.: Early progression as a predictor of survival in marginal zone lymphomas: an analysis from the FIL-NF10 study. Blood 134 (10): 798-801, 2019.

- Vallisa D, Bernuzzi P, Arcaini L, et al.: Role of anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment in HCV-related, low-grade, B-cell, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: a multicenter Italian experience. J Clin Oncol 23 (3): 468-73, 2005.

- Isaacson PG: Gastrointestinal lymphoma. Hum Pathol 25 (10): 1020-9, 1994.

- Lecuit M, Abachin E, Martin A, et al.: Immunoproliferative small intestinal disease associated with Campylobacter jejuni. N Engl J Med 350 (3): 239-48, 2004.

- Arcaini L, Paulli M, Boveri E, et al.: Splenic and nodal marginal zone lymphomas are indolent disorders at high hepatitis C virus seroprevalence with distinct presenting features but similar morphologic and phenotypic profiles. Cancer 100 (1): 107-15, 2004.

- Arcaini L, Rossi D, Paulli M: Splenic marginal zone lymphoma: from genetics to management. Blood 127 (17): 2072-81, 2016.

- Parry-Jones N, Matutes E, Gruszka-Westwood AM, et al.: Prognostic features of splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes: a report on 129 patients. Br J Haematol 120 (5): 759-64, 2003.

- Arcaini L, Lazzarino M, Colombo N, et al.: Splenic marginal zone lymphoma: a prognostic model for clinical use. Blood 107 (12): 4643-9, 2006.

- Iannitto E, Ambrosetti A, Ammatuna E, et al.: Splenic marginal zone lymphoma with or without villous lymphocytes. Hematologic findings and outcomes in a series of 57 patients. Cancer 101 (9): 2050-7, 2004.

- Hermine O, Lefrère F, Bronowicki JP, et al.: Regression of splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes after treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 347 (2): 89-94, 2002.

- Kelaidi C, Rollot F, Park S, et al.: Response to antiviral treatment in hepatitis C virus-associated marginal zone lymphomas. Leukemia 18 (10): 1711-6, 2004.

- de Bruin PC, Beljaards RC, van Heerde P, et al.: Differences in clinical behaviour and immunophenotype between primary cutaneous and primary nodal anaplastic large cell lymphoma of T-cell or null cell phenotype. Histopathology 23 (2): 127-35, 1993.

- Willemze R, Beljaards RC: Spectrum of primary cutaneous CD30 (Ki-1)-positive lymphoproliferative disorders. A proposal for classification and guidelines for management and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol 28 (6): 973-80, 1993.

- Kempf W, Pfaltz K, Vermeer MH, et al.: EORTC, ISCL, and USCLC consensus recommendations for the treatment of primary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: lymphomatoid papulosis and primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma. Blood 118 (15): 4024-35, 2011.

Aggressive NHL

Aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) includes the following subtypes:

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

- Mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma).

- Follicular large cell lymphoma.

- Anaplastic large cell lymphoma.

- Extranodal NK–/T-cell lymphoma.

- Lymphomatoid granulomatosis.

- Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma.

- Peripheral T-cell lymphoma.

- Enteropathy-type intestinal T-cell lymphoma.

- Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (intravascular lymphomatosis).

- Burkitt lymphoma/diffuse small noncleaved-cell lymphoma.

- Lymphoblastic lymphoma.

- Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma.

- Mantle cell lymphoma.

- Polymorphic posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder.

- True histiocytic lymphoma.

- Primary effusion lymphoma.

- Plasmablastic lymphoma.

Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of NHL and comprises 30% of newly diagnosed cases.[

Some cases of large B-cell lymphoma have a prominent background of reactive T cells and often of histiocytes, so-called T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma. This subtype of large cell lymphoma has frequent liver, spleen, and bone marrow involvement; however, the outcome is equivalent to that of similarly staged patients with DLBCL.[

Prognosis

Most patients with localized disease are curable with combined-modality therapy or combination chemotherapy alone.[

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network International Prognostic Index (IPI) for aggressive NHL (diffuse large cell lymphoma) identifies the following five significant risk factors prognostic of OS and their associated risk scores:[

- Age.

- <40 years: 0.

- 41–60 years: 1.

- 61–75 years: 2.

- >75 years: 3.

- Stage III/IV: 1.

- Performance status 2/3/4: 1.

- Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

- Normalized: 0.

- >1x–3x: 1.

- >3x: 2.

- Number of extranodal sites ≥2: 1.

Risk scores:

- Low (0 or 1): 5-year OS rate, 96%; progression-free survival (PFS) rate, 91%.

- Low intermediate (2 or 3): 5-year OS rate, 82%; PFS rate, 74%.

- High intermediate (4 or 5): 5-year OS rate, 64%; PFS rate, 51%.

- High (>6): 5-year OS rate, 33%; PFS rate, 30%.

Age-adjusted and stage-adjusted modifications of this IPI are used for younger patients with localized disease.[

The BCL2 gene and rearrangement of the MYC gene or dual overexpression of the MYC gene, or both, confer a particularly poor prognosis.[

In a retrospective review of 117 patients with relapsed or refractory DLBCL who underwent autologous SCT, the 4-year OS rate was 25% for double-hit lymphomas (rearrangement of BCL2 and MYC), 61% for double-expressor lymphomas (no rearrangement, but increased expression of BCL2 and MYC), and 70% for patients without these features.[

Molecular profiles of gene expression using DNA microarrays may help to stratify patients in the future for therapies directed at specific targets and to better predict survival after standard chemotherapy.[

Central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis

The CNS-IPI tool predicts which patients have a CNS relapse risk exceeding 10%. It was developed by the German Lymphoma Study Group and validated by the British Columbia Cancer Agency database. The presence of four to six of the CNS-IPI risk factors (age >60 years, performance status ≥2, elevated LDH, stage III or IV disease, >1 extranodal site, or involvement of the kidneys or adrenal glands) was used to define a high-risk group for CNS recurrence (a 12% risk of CNS involvement by 2 years).[

CNS prophylaxis (usually with four to six doses of intrathecal methotrexate) is often recommended for patients with testicular involvement.[

The addition of rituximab to cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone (CHOP)-based regimens has significantly reduced the risk of CNS relapse in retrospective analyses.[

Primary Mediastinal Large B-cell Lymphoma

Primary mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) is a subset of DLBCL with molecular characteristics that are most similar to nodular-sclerosing Hodgkin lymphoma (HL). Mediastinal lymphomas with features intermediate between primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and nodular-sclerosing HL are called mediastinal gray-zone lymphomas.[

Prognosis and therapy are the same as for other comparably staged patients with DLBCL. Uncontrolled, phase II studies employing dose-adjusted R-EPOCH (etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin plus rituximab) or R-CHOP show high cure rates while avoiding any mediastinal radiation.[

A retrospective review of 109 patients with PMBCL showed that 63% had a negative end-of-treatment PET-CT (EOT-PET-CT) (Deauville score 1–3).[

In situations where mediastinal radiation therapy would encompass the left side of the heart or would increase breast cancer risk in young female patients, proton therapy may be considered to reduce radiation dose to organs at risk.[

Because PMBCL is characterized by high expression of programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and variable expression of CD30, a phase II study evaluated nivolumab plus brentuximab vedotin in 30 patients with relapsed disease. With a median follow-up of 11.1 months, the objective response rate (ORR) was 73% (95% CI, 54%−88%).[

Follicular Large Cell Lymphoma

Prognosis

The natural history of follicular large cell lymphoma remains controversial.[

Therapeutic approaches

Treatment of follicular large cell lymphoma is more similar to treatment of aggressive NHL than it is to the treatment of indolent NHL. In support of this approach, treatment with high-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic peripheral SCT shows the same curative potential in patients with follicular large cell lymphoma who relapse as it does in patients with diffuse large cell lymphoma who relapse.[

Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

Anaplastic large cell lymphomas (ALCL) may be confused with carcinomas and are associated with the Ki-1 (CD30) antigen. These lymphomas are usually of T-cell origin, often present with extranodal disease, and are found especially in the skin.[

The translocation of chromosomes 2 and 5 creates a unique fusion protein with a nucleophosmin-anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK).[

Patients whose lymphomas express ALK (immunohistochemistry) are usually younger and may have systemic symptoms, extranodal disease, and advanced-stage disease; however, they have a more favorable survival rate than that of ALK-negative patients.[

In a prospective randomized trial of 452 patients with CD30-positive T-cell lymphoma, 70% of whom had ALCL (22% ALK-positive and 48% ALK-negative patients), the previously used standard regimen, CHOP, was compared with brentuximab vedotin (an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody conjugated to a cytotoxic agent) combined with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone.[

ALCL in children is usually characterized by systemic and cutaneous disease and has high response rates and good OS with doxorubicin-based combination chemotherapy.[

Extranodal Natural Killer (NK)-/T-cell Lymphoma

Extranodal natural killer (NK)-/T-cell lymphoma (nasal type) is an aggressive lymphoma marked by extensive necrosis and angioinvasion, most often presenting in extranodal sites, in particular the nasal or paranasal sinus region.[

The increased risk of CNS involvement and of local recurrence has led to recommendations for radiation therapy locally, concurrently, before the start of chemotherapy or between cycle two and three of chemotherapy, and for intrathecal prophylaxis and/or prophylactic cranial radiation therapy.[

A retrospective review of 1,273 early-stage patients stratified them into a low-risk group and high-risk group using stage, age, LDH, performance status, and primary tumor invasion. Low-risk patients fared best with radiation therapy alone,[

In a retrospective review of 303 previously untreated patients from an international consortium who received nonanthracycline chemotherapy, the OS rates were identical for early-stage patients (72%−74% at 5 years) who received either concurrent chemotherapy and radiation therapy or chemotherapy followed by radiation therapy.[

Higher doses of radiation therapy administered at more than 50 Gy are associated with improved outcomes according to anecdotal reports.[

Lymphomatoid Granulomatosis

Lymphomatoid granulomatosis is an EBV-positive large B-cell lymphoma with a predominant T-cell background.[

Patients are managed like others with diffuse large cell lymphoma and require doxorubicin-based combination chemotherapy.

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell Lymphoma

Angioimmunoblastic T-cell lymphoma (AITL or ATCL) was formerly called angioimmunoblastic lymphadenopathy with dysproteinemia. Characterized by clonal T-cell receptor gene rearrangement, this entity is managed like diffuse large cell lymphoma.[

Doxorubicin-based combination chemotherapy, such as the CHOP regimen, is recommended as it is for other aggressive lymphomas.[

Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma

Patients with peripheral T-cell lymphoma have diffuse large cell or diffuse mixed lymphoma that expresses a cell surface phenotype of a postthymic (or peripheral) T-cell expressing CD4 or CD8 but not both together.[

Prognosis

Most investigators report worse response and survival rates for patients with peripheral T-cell lymphomas than for patients with comparably staged B-cell aggressive lymphomas.[

Therapeutic approaches

Therapy involves doxorubicin-based combination chemotherapy (such as CHOP or CHOPE [CHOP plus etoposide]), which is also used for DLBCL.[

A randomized prospective trial included 104 patients younger than 61 years with stage II, III, or IV peripheral T-cell lymphoma (excluding ALK-positive ALCL). Patients received either autologous SCT or allogeneic SCT as consolidation therapy after induction with CHOEP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, etoposide, and prednisone) followed by DHAP (dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin).[

In a prospective trial of 109 evaluable patients with relapsing disease, treatment with pralatrexate resulted in a 30% response rate and a median 10-month duration of response.[

An unusual type of peripheral T-cell lymphoma occurring mostly in young men, hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma, appears to be localized to the hepatic and splenic sinusoids, with cell surface expression of the T-cell receptor gamma/delta.[

Enteropathy-type Intestinal T-cell Lymphoma

Enteropathy-type intestinal T-cell lymphoma involves the small bowel of patients with gluten-sensitive enteropathy (celiac sprue).[

Therapy is with doxorubicin-based combination chemotherapy, but relapse rates appear higher than for comparably staged diffuse large cell lymphoma.[

Intravascular Large B-cell Lymphoma (Intravascular Lymphomatosis)

Intravascular lymphomatosis is characterized by large cell lymphoma confined to the intravascular lumen. The brain, kidneys, lungs, and skin are the organs most likely affected by intravascular lymphomatosis.

With the use of aggressive R-CHOP–based combination chemotherapy, as is used in DLBCL, the prognosis is similar to that of conventional stage IV DLBCL.[

Burkitt Lymphoma/Diffuse Small Noncleaved-cell Lymphoma

Burkitt lymphoma/diffuse small noncleaved-cell lymphoma typically involves younger patients and represents the most common type of pediatric NHL.[

In some patients with larger B cells, there is morphologic overlap with DLBCL. These Burkitt-like large cell lymphomas show MYC deregulation, extremely high proliferation rates, and a gene-expression profile as expected for classic Burkitt lymphoma.[

Therapeutic approaches

Treatment of Burkitt lymphoma/diffuse small noncleaved-cell lymphoma involves aggressive multidrug regimens in combination with rituximab, similar to those used for the advanced-stage aggressive lymphomas (diffuse large cell).[

Lymphoblastic Lymphoma

Lymphoblastic lymphoma (precursor T-cell) is a very aggressive form of NHL. It often, but not exclusively, occurs in young patients.[

Treatment is usually patterned after that for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Intensive combination chemotherapy with or without bone marrow transplantation is the standard treatment for this aggressive histologic type of NHL.[

Adult T-cell Leukemia/Lymphoma

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) is caused by infection with the retrovirus human T-lymphotrophic virus 1 and is frequently associated with lymphadenopathy, hypercalcemia, circulating leukemic cells, bone and skin involvement, hepatosplenomegaly, a rapidly progressive course, and poor response to combination chemotherapy.[

- Acute (aggressive course with leukemia, with or without extranodal or nodal involvement).

- Lymphoma (aggressive course with lymphadenopathy and no leukemia).

- Chronic (indolent course with leukemia and lymphadenopathy).

- Smoldering (indolent course with only leukemia).

The acute and lymphoma types of ATL have done poorly with strategies of combination chemotherapy and allogeneic SCT with a median OS under 1 year.[

The combination of zidovudine and interferon-alpha has activity against ATL, even for patients who failed previous cytotoxic therapy. Durable remissions are seen in the majority of presenting patients with this combination but are not seen in patients with the lymphoma subtype of ATL.[

Mantle Cell Lymphoma

Mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is found in lymph nodes, the spleen, bone marrow, blood, and sometimes the gastrointestinal system (lymphomatous polyposis).[

Like the low-grade lymphomas, MCL appears incurable with anthracycline-based chemotherapy and occurs in older patients with generally asymptomatic advanced-stage disease. The median survival, however, is significantly shorter (5–7 years) than that of other lymphomas, and this histology is now considered to be an aggressive lymphoma.[

Therapeutic approaches

Asymptomatic patients with low-risk scores on the IPI may do well when initial therapy is deferred.[

It is unclear which therapeutic approach offers the best long-term survival in this clinicopathologic entity.

Previously treated patients who received the B-cell receptor-inhibitor, ibrutinib, had a response rate of 86% (21% CR rate) and a median PFS of 14 months.[

A prospective randomized trial included 523 patients aged 65 years and older with MCL. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either ibrutinib, bendamustine, and rituximab or bendamustine and rituximab alone.[

In a prospective randomized trial, 560 patients older than 60 years and not eligible for SCT were given either R-CHOP or R-FC (rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide) for six to eight cycles, followed by maintenance therapy in responders randomly assigned to rituximab or interferon-alpha maintenance therapy.[

A prospective randomized trial of 497 patients younger than 65 years compared six cycles of R-CHOP with six cycles of alternating R-CHOP and R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, cytarabine, and cisplatin), with both groups then receiving autologous SCT.[

Randomized trials have not confirmed OS benefits in patients who receive consolidation therapy with autologous or allogeneic SCT.[

In a prospective trial (NCT00921414) of 299 patients who were previously untreated for MCL, 257 responders received four courses of R-DHAP and autologous SCT. The patients were randomly assigned to receive rituximab maintenance therapy for 3 years versus no maintenance therapy. After randomization, a median follow-up at 50.2 months showed the rate of PFS at 4-years favored the rituximab-maintenance arm at 83% (95% CI, 73%–88%) versus the no-maintenance arm at 64% (95% CI, 55%–73%; P < .001). The 4-year OS rate also favored the rituximab-maintenance arm at 89% (95% CI, 81%–94%) versus the no-maintenance arm at 80% (95% CI, 72%–88%; P = .04).[

Lenalidomide with or without rituximab also shows response rates of around 50% in relapsed patients, with even higher response rates for previously untreated patients.[

Acalabrutinib (another B-cell receptor inhibitor via the Bruton tyrosine kinase pathway) was studied in 124 patients with relapsed/refractory MCL.[

Patients with relapsed or refractory MCL whose disease did not respond to ibrutinib or acalabrutinib were enrolled in a phase II trial using brexucabtagene autoleucel, an anti-CD19 chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.[

Routine administration of CNS prophylaxis in high-risk MCL has never been studied in a prospective randomized trial. The use of intrathecal or high-dose methotrexate or the use of systemic therapies with CNS penetration like ibrutinib, high-dose cytarabine, or venetoclax, have not been studied and proven efficacious in this situation.[

Posttransplantation Lymphoproliferative Disorder

Patients who undergo transplantation of the heart, lung, liver, kidney, or pancreas usually require lifelong immunosuppression. This may result in posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) in 1% to 3% of recipients, which appears as an aggressive lymphoma.[

Prognosis

Poor performance status, grafted organ involvement, high IPI, elevated LDH, and multiple sites of disease are poor prognostic factors for PTLD.[

Therapeutic options

In some cases, withdrawal of immunosuppression results in eradication of the lymphoma.[

True Histiocytic Lymphoma

True histiocytic lymphomas are very rare tumors that show histiocytic differentiation and express histiocytic markers in the absence of B-cell or T-cell lineage-specific immunologic markers.[

Therapeutic options

Therapy is modeled after the treatment of comparably staged diffuse large cell lymphomas, but the optimal approach remains to be defined.

Primary Effusion Lymphoma

Primary effusion lymphoma presents exclusively or mainly in the pleural, pericardial, or abdominal cavities in the absence of an identifiable tumor mass.[

Prognosis

The prognosis of primary effusion lymphoma is extremely poor.

Therapeutic approaches

Therapy is usually modeled after the treatment of comparably staged diffuse large cell lymphomas.

Plasmablastic Lymphoma

Plasmablastic lymphoma is most often seen in patients with HIV infection and is characterized by CD20-negative large B cells with plasmacytic features. This type of lymphoma has a very aggressive clinical course, including poor responses and short remissions with standard chemotherapy.[

References:

- Sehn LH, Salles G: Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N Engl J Med 384 (9): 842-858, 2021.

- Delabie J, Vandenberghe E, Kennes C, et al.: Histiocyte-rich B-cell lymphoma. A distinct clinicopathologic entity possibly related to lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin's disease, paragranuloma subtype. Am J Surg Pathol 16 (1): 37-48, 1992.

- Achten R, Verhoef G, Vanuytsel L, et al.: T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphoma: a distinct clinicopathologic entity. J Clin Oncol 20 (5): 1269-77, 2002.

- Bouabdallah R, Mounier N, Guettier C, et al.: T-cell/histiocyte-rich large B-cell lymphomas and classical diffuse large B-cell lymphomas have similar outcome after chemotherapy: a matched-control analysis. J Clin Oncol 21 (7): 1271-7, 2003.

- Ghesquières H, Berger F, Felman P, et al.: Clinicopathologic characteristics and outcome of diffuse large B-cell lymphomas presenting with an associated low-grade component at diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 24 (33): 5234-41, 2006.

- Miller TP, Dahlberg S, Cassady JR, et al.: Chemotherapy alone compared with chemotherapy plus radiotherapy for localized intermediate- and high-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med 339 (1): 21-6, 1998.

- Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, et al.: CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 346 (4): 235-42, 2002.

- Coiffier B: State-of-the-art therapeutics: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 23 (26): 6387-93, 2005.

- Habermann TM, Weller EA, Morrison VA, et al.: Rituximab-CHOP versus CHOP alone or with maintenance rituximab in older patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 24 (19): 3121-7, 2006.

- Zhou Z, Sehn LH, Rademaker AW, et al.: An enhanced International Prognostic Index (NCCN-IPI) for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era. Blood 123 (6): 837-42, 2014.

- Møller MB, Christensen BE, Pedersen NT: Prognosis of localized diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in younger patients. Cancer 98 (3): 516-21, 2003.

- Maurer MJ, Ghesquières H, Link BK, et al.: Diagnosis-to-Treatment Interval Is an Important Clinical Factor in Newly Diagnosed Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma and Has Implication for Bias in Clinical Trials. J Clin Oncol 36 (16): 1603-1610, 2018.

- Scott DW, King RL, Staiger AM, et al.: High-grade B-cell lymphoma with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma morphology. Blood 131 (18): 2060-2064, 2018.

- Horn H, Ziepert M, Becher C, et al.: MYC status in concert with BCL2 and BCL6 expression predicts outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 121 (12): 2253-63, 2013.

- Staiger AM, Ziepert M, Horn H, et al.: Clinical Impact of the Cell-of-Origin Classification and the MYC/ BCL2 Dual Expresser Status in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Treated Within Prospective Clinical Trials of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol 35 (22): 2515-2526, 2017.

- Howlett C, Snedecor SJ, Landsburg DJ, et al.: Front-line, dose-escalated immunochemotherapy is associated with a significant progression-free survival advantage in patients with double-hit lymphomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Haematol 170 (4): 504-14, 2015.

- Sesques P, Johnson NA: Approach to the diagnosis and treatment of high-grade B-cell lymphomas with MYC and BCL2 and/or BCL6 rearrangements. Blood 129 (3): 280-288, 2017.

- Landsburg DJ, Falkiewicz MK, Maly J, et al.: Outcomes of Patients With Double-Hit Lymphoma Who Achieve First Complete Remission. J Clin Oncol 35 (20): 2260-2267, 2017.

- Herrera AF, Mei M, Low L, et al.: Relapsed or Refractory Double-Expressor and Double-Hit Lymphomas Have Inferior Progression-Free Survival After Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation. J Clin Oncol 35 (1): 24-31, 2017.

- Canellos GP: CHOP may have been part of the beginning but certainly not the end: issues in risk-related therapy of large-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 15 (5): 1713-6, 1997.

- Sha C, Barrans S, Cucco F, et al.: Molecular High-Grade B-Cell Lymphoma: Defining a Poor-Risk Group That Requires Different Approaches to Therapy. J Clin Oncol 37 (3): 202-212, 2019.

- Hu S, Xu-Monette ZY, Balasubramanyam A, et al.: CD30 expression defines a novel subgroup of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with favorable prognosis and distinct gene expression signature: a report from the International DLBCL Rituximab-CHOP Consortium Program Study. Blood 121 (14): 2715-24, 2013.

- Maurer MJ, Ghesquières H, Jais JP, et al.: Event-free survival at 24 months is a robust end point for disease-related outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with immunochemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 32 (10): 1066-73, 2014.

- Schmitz N, Zeynalova S, Nickelsen M, et al.: CNS International Prognostic Index: A Risk Model for CNS Relapse in Patients With Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma Treated With R-CHOP. J Clin Oncol 34 (26): 3150-6, 2016.

- Zucca E, Conconi A, Mughal TI, et al.: Patterns of outcome and prognostic factors in primary large-cell lymphoma of the testis in a survey by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol 21 (1): 20-7, 2003.

- Vitolo U, Chiappella A, Ferreri AJ, et al.: First-line treatment for primary testicular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with rituximab-CHOP, CNS prophylaxis, and contralateral testis irradiation: final results of an international phase II trial. J Clin Oncol 29 (20): 2766-72, 2011.

- Cheah CY, Wirth A, Seymour JF: Primary testicular lymphoma. Blood 123 (4): 486-93, 2014.

- Boehme V, Schmitz N, Zeynalova S, et al.: CNS events in elderly patients with aggressive lymphoma treated with modern chemotherapy (CHOP-14) with or without rituximab: an analysis of patients treated in the RICOVER-60 trial of the German High-Grade Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (DSHNHL). Blood 113 (17): 3896-902, 2009.

- Glantz MJ, Cole BF, Recht L, et al.: High-dose intravenous methotrexate for patients with nonleukemic leptomeningeal cancer: is intrathecal chemotherapy necessary? J Clin Oncol 16 (4): 1561-7, 1998.

- Puckrin R, El Darsa H, Ghosh S, et al.: Ineffectiveness of high-dose methotrexate for prevention of CNS relapse in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol 96 (7): 764-771, 2021.

- Jeong H, Cho H, Kim H, et al.: Efficacy and safety of prophylactic high-dose MTX in high-risk DLBCL: a treatment intent-based analysis. Blood Adv 5 (8): 2142-2152, 2021.

- Villa D, Connors JM, Shenkier TN, et al.: Incidence and risk factors for central nervous system relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: the impact of the addition of rituximab to CHOP chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 21 (5): 1046-52, 2010.

- Ferreri AJ, Donadoni G, Cabras MG, et al.: High Doses of Antimetabolites Followed by High-Dose Sequential Chemoimmunotherapy and Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation in Patients With Systemic B-Cell Lymphoma and Secondary CNS Involvement: Final Results of a Multicenter Phase II Trial. J Clin Oncol 33 (33): 3903-10, 2015.

- Schmitz N, Wu HS: Advances in the Treatment of Secondary CNS Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 33 (33): 3851-3, 2015.

- van Besien K, Kelta M, Bahaguna P: Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma: a review of pathology and management. J Clin Oncol 19 (6): 1855-64, 2001.

- Dunleavy K, Wilson WH: Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma and mediastinal gray zone lymphoma: do they require a unique therapeutic approach? Blood 125 (1): 33-9, 2015.

- Dunleavy K, Pittaluga S, Maeda LS, et al.: Dose-adjusted EPOCH-rituximab therapy in primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 368 (15): 1408-16, 2013.