Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage

Plans through your employer

Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

Learn

Living or working abroad?

Cannabis and Cannabinoids (PDQ®): Integrative, alternative, and complementary therapies - Health Professional Information [NCI]

Overview

This cancer information summary provides an overview of the use of Cannabis and its components as a treatment for people with cancer-related symptoms caused by the disease itself or its treatment.

This summary contains the following key information:

- Cannabis has been used for medicinal purposes for thousands of years.

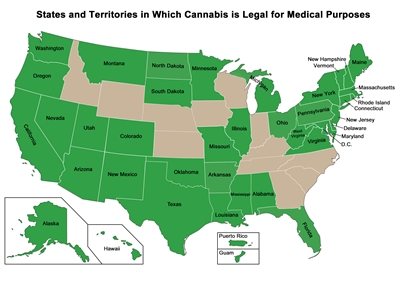

- By federal law, the possession of Cannabis is illegal in the United States, except within approved research settings; however, a growing number of states, territories, and the District of Columbia have enacted laws to legalize its medical and/or recreational use.

- The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has not approved Cannabis as a treatment for cancer or any other medical condition.

- Chemical components of Cannabis, called cannabinoids, activate specific receptors throughout the body to produce pharmacological effects, particularly in the central nervous system and the immune system.

- Commercially available cannabinoids, such as dronabinol and nabilone, are approved drugs for the treatment of cancer-related side effects.

- Cannabinoids may have benefits in the treatment of cancer-related side effects.

Many of the medical and scientific terms used in this summary are hypertext linked (at first use in each section) to the

Reference citations in some PDQ cancer information summaries may include links to external websites that are operated by individuals or organizations for the purpose of marketing or advocating the use of specific treatments or products. These reference citations are included for informational purposes only. Their inclusion should not be viewed as an endorsement of the content of the websites, or of any treatment or product, by the PDQ Integrative, Alternative, and Complementary Therapies Editorial Board or the National Cancer Institute.

General Information

Cannabis, also known as marijuana, originated in Central Asia but is grown worldwide today. In the United States, it is a controlled substance and is classified as a Schedule I agent (a drug with a high potential for abuse, and no currently accepted medical use). The Cannabis plant produces a resin containing 21-carbon terpenophenolic compounds called cannabinoids, in addition to other compounds found in plants, such as terpenes and flavonoids. The highest concentration of cannabinoids is found in the female flowers of the plant.[

Clinical trials conducted on medicinal Cannabis are limited. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has not approved the use of Cannabis as a treatment for any medical condition, although both isolated THC and CBD pharmaceuticals are licensed and approved. To conduct clinical drug research with botanical Cannabis in the United States, researchers must file an Investigational New Drug (IND) application with the FDA, obtain a Schedule I license from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, and obtain approval from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

In the 2018 United States Farm Bill, the term hemp is used to describe cultivars of the Cannabis species that contain less than 0.3% THC. Hemp oil or CBD oil are products manufactured from extracts of industrial hemp (i.e., low-THC cannabis cultivars), whereas hemp seed oil is an edible fatty oil that is essentially cannabinoid-free (see

| Name/Material | Constituents/Composition | |

|---|---|---|

| CBD = cannabidiol; THC = tetrahydrocannabinol. | ||

| Cannabis species, includingC. sativa | Cannabinoids; also terpenoids and flavonoids | |

| • Hemp (aka industrial hemp) | Low Δ9 -THC (<0.3%); high CBD | |

| • Marijuana/marihuana | High Δ9 -THC (>0.3%); low CBD | |

| Nabiximols (trade name: Sativex) | Mixture of ethanol extracts ofCannabis species; contains Δ9 -THC and CBD in a 1:1 ratio | |

| Hemp oil/CBD oil | Solution of asolventextract fromCannabis flowers and/or leaves dissolved in an edible oil; typically contains 1%–5% CBD | |

| Hemp seed oil | Edible, fatty oil produced fromCannabis seeds; contains no or only traces of cannabinoids | |

| Dronabinol(trade names: Marinol and Syndros) | SyntheticΔ9 -THC | |

| Nabilone(trade names:Cesametand Canemes) | Synthetic THCanalogue | |

| Cannabidiol (trade name: Epidiolex) | Highly purified (>98%), plant-derived CBD | |

The potential benefits of medicinal Cannabis for people living with cancer include the following:[

- Antiemetic effects.

- Appetite stimulation.

- Pain relief.

- Improved sleep.

In a survey of 934 adult patients with cancer at a National Cancer Institute (NCI)-designated comprehensive cancer center, the top five reasons for Cannabis use included sleep (57%), stress (56%), pain (51%), appetite (49%), and nausea (38%).[

This summary will review the role of Cannabis and the cannabinoids in the treatment of people with cancer and disease-related or treatment-related side effects. The NCI hosted a virtual meeting, the NCI Cannabis, Cannabinoids, and Cancer Research Symposium, on December 15–18, 2020. The seven sessions are summarized in the

References:

- Adams IB, Martin BR: Cannabis: pharmacology and toxicology in animals and humans. Addiction 91 (11): 1585-614, 1996.

- Abrams DI: Integrating cannabis into clinical cancer care. Curr Oncol 23 (2): S8-S14, 2016.

- Brasky TM, Newton AM, Conroy S, et al.: Marijuana and Cannabidiol Use Prevalence and Symptom Management Among Patients with Cancer. Cancer Res Commun 3 (9): 1917-1926, 2023.

- Doblin RE, Kleiman MA: Marijuana as antiemetic medicine: a survey of oncologists' experiences and attitudes. J Clin Oncol 9 (7): 1314-9, 1991.

- Ellison GL, Alejandro Salicrup L, Freedman AN, et al.: The National Cancer Institute and Cannabis and Cannabinoids Research. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2021 (58): 35-38, 2021.

- Sexton M, Garcia JM, Jatoi A, et al.: The Management of Cancer Symptoms and Treatment-Induced Side Effects With Cannabis or Cannabinoids. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2021 (58): 86-98, 2021.

- Cooper ZD, Abrams DI, Gust S, et al.: Challenges for Clinical Cannabis and Cannabinoid Research in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2021 (58): 114-122, 2021.

- Braun IM, Abrams DI, Blansky SE, et al.: Cannabis and the Cancer Patient. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2021 (58): 68-77, 2021.

- Ward SJ, Lichtman AH, Piomelli D, et al.: Cannabinoids and Cancer Chemotherapy-Associated Adverse Effects. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2021 (58): 78-85, 2021.

- McAllister SD, Abood ME, Califano J, et al.: Cannabinoid Cancer Biology and Prevention. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2021 (58): 99-106, 2021.

- Abrams DI, Velasco G, Twelves C, et al.: Cancer Treatment: Preclinical & Clinical. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2021 (58): 107-113, 2021.

History

Cannabis use for medicinal purposes dates back at least 3,000 years.[

In 1937, the U.S. Treasury Department introduced the Marihuana Tax Act. This Act imposed a levy of $1 per ounce for medicinal use of Cannabis and $100 per ounce for nonmedical use. Physicians in the United States were the principal opponents of the Act. The American Medical Association (AMA) opposed the Act because physicians were required to pay a special tax for prescribing Cannabis, use special order forms to procure it, and keep special records concerning its professional use. In addition, the AMA believed that objective evidence that Cannabis was harmful was lacking and that passage of the Act would impede further research into its medicinal worth.[

In 1951, Congress passed the Boggs Act, which for the first time included Cannabis with narcotic drugs. In 1970, with the passage of the Controlled Substances Act, marijuana was classified by Congress as a Schedule I drug. Drugs in Schedule I are distinguished as having no currently accepted medicinal use in the United States. Other Schedule I substances include heroin, LSD, mescaline, and methaqualone.

Despite its designation as having no medicinal use, Cannabis was distributed by the U.S. government to patients on a case-by-case basis under the Compassionate Use Investigational New Drug program established in 1978. Distribution of Cannabis through this program was closed to new patients in 1992.[

Figure 1. A map showing the U.S. states and territories that have approved the medical use of Cannabis. Last reviewed: 10/22/2024

The main psychoactive constituent of Cannabis was identified as delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). In 1986, an isomer of synthetic delta-9-THC in sesame oil was licensed and approved for the treatment of chemotherapy -associated nausea and vomiting under the generic name dronabinol. Clinical trials determined that dronabinol was as effective as or better than other antiemetic agents available at the time.[

In recent decades, the neurobiology of cannabinoids has been analyzed.[

Nabiximols (Sativex), a Cannabisextract with a 1:1 ratio of THC:CBD, is approved in Canada (under the Notice of Compliance with Conditions) for symptomatic relief of pain in advanced cancer and multiple sclerosis.[

References:

- Abel EL: Marihuana, The First Twelve Thousand Years. Plenum Press, 1980.

Also available online . Last accessed June 2, 2021. - Joy JE, Watson SJ, Benson JA, eds.: Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing the Science Base. National Academy Press, 1999.

Also available online . Last accessed June 2, 2021. - Mack A, Joy J: Marijuana As Medicine? The Science Beyond the Controversy. National Academy Press, 2001.

Also available online . Last accessed June 2, 2021. - Booth M: Cannabis: A History. St Martin's Press, 2003.

- Russo EB, Jiang HE, Li X, et al.: Phytochemical and genetic analyses of ancient cannabis from Central Asia. J Exp Bot 59 (15): 4171-82, 2008.

- Schaffer Library of Drug Policy: The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937: Taxation of Marihuana. Washington, DC: House of Representatives, Committee on Ways and Means, 1937.

Available online . Last accessed June 2, 2021. - Sarma ND, Waye A, ElSohly MA, et al.: Cannabis Inflorescence for Medical Purposes: USP Considerations for Quality Attributes. J Nat Prod 83 (4): 1334-1351, 2020.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. The National Academies Press, 2017.

- Sallan SE, Zinberg NE, Frei E: Antiemetic effect of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 293 (16): 795-7, 1975.

- Gorter R, Seefried M, Volberding P: Dronabinol effects on weight in patients with HIV infection. AIDS 6 (1): 127, 1992.

- Beal JE, Olson R, Laubenstein L, et al.: Dronabinol as a treatment for anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manage 10 (2): 89-97, 1995.

- Adams R, Hunt M, Clark JH: Structure of cannabidiol: a product isolated from the marihuana extract of Minnesota wild hemp. J Am Chem Soc 62 (1): 196-200, 1940.

Also available online . Last accessed June 2, 2021. - Devane WA, Dysarz FA, Johnson MR, et al.: Determination and characterization of a cannabinoid receptor in rat brain. Mol Pharmacol 34 (5): 605-13, 1988.

- Devane WA, Hanus L, Breuer A, et al.: Isolation and structure of a brain constituent that binds to the cannabinoid receptor. Science 258 (5090): 1946-9, 1992.

- Pertwee RG, Howlett AC, Abood ME, et al.: International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: beyond CB₁ and CB₂. Pharmacol Rev 62 (4): 588-631, 2010.

- Felder CC, Glass M: Cannabinoid receptors and their endogenous agonists. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 38: 179-200, 1998.

- Pacher P, Bátkai S, Kunos G: The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev 58 (3): 389-462, 2006.

- Howard P, Twycross R, Shuster J, et al.: Cannabinoids. J Pain Symptom Manage 46 (1): 142-9, 2013.

- Nabiximols. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information, 2009.

Available online . Last accessed June 2, 2021.

Laboratory / Animal / Preclinical Studies

Cannabinoids are a group of 21-carbon–containing terpenophenolic compounds produced uniquely by Cannabis species (e.g., Cannabis sativa L.).[

Antitumor Effects

One study in mice and rats suggested that cannabinoids may have a protective effect against the development of certain types of tumors.[

Cannabinoids may cause antitumor effects by various mechanisms, including induction of cell death, inhibition of cell growth, and inhibition of tumor angiogenesis invasion and metastasis.[

The effects of delta-9-THC and a synthetic agonist of the CB2 receptor were investigated in HCC.[

An in vitro study of the effect of CBD on programmed cell death in breast cancer cell lines found that CBD induced programmed cell death, independent of the CB1, CB2, or vanilloid receptors. CBD inhibited the survival of both estrogen receptor–positive and estrogen receptor–negative breast cancer cell lines, inducing apoptosis in a concentration-dependent manner while having little effect on nontumorigenic mammary cells.[

CBD has also been demonstrated to exert a chemopreventive effect in a mouse model of colon cancer.[

Another investigation into the antitumor effects of CBD examined the role of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1).[

In an in vivo model using severe combined immunodeficient mice, subcutaneous tumors were generated by inoculating the animals with cells from human non-small cell lung carcinoma cell lines.[

In addition, both plant-derived and endogenous cannabinoids have been studied for anti-inflammatory effects. A mouse study demonstrated that endogenous cannabinoid system signaling is likely to provide intrinsic protection against colonic inflammation.[

CBD may also enhance uptake of cytotoxic drugs into malignant cells. Activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid type 2 (TRPV2) has been shown to inhibit proliferation of human glioblastoma multiforme cells and overcome resistance to the chemotherapy agent carmustine. [

Antiemetic Effects

Preclinical research suggests that emetic circuitry is tonically controlled by endocannabinoids. The antiemetic action of cannabinoids is believed to be mediated via interaction with the 5-hydroxytryptamine 3 (5-HT3) receptor. CB1 receptors and 5-HT3 receptors are colocalized on gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic neurons, where they have opposite effects on GABA release.[

Appetite Stimulation

Many animal studies have previously demonstrated that delta-9-THC and other cannabinoids have a stimulatory effect on appetite and increase food intake. It is believed that the endogenous cannabinoid system may serve as a regulator of feeding behavior. The endogenous cannabinoid anandamide potently enhances appetite in mice.[

Analgesia

Understanding the mechanism of cannabinoid-induced analgesia has been increased through the study of cannabinoid receptors, endocannabinoids, and synthetic agonists and antagonists. Cannabinoids produce analgesia through supraspinal, spinal, and peripheral modes of action, acting on both ascending and descending pain pathways.[

Cannabinoids may also contribute to pain modulation through an anti-inflammatory mechanism; a CB2 effect with cannabinoids acting on mast cell receptors to attenuate the release of inflammatory agents, such as histamine and serotonin, and on keratinocytes to enhance the release of analgesic opioids has been described.[

Cannabinoids have been shown to prevent chemotherapy-induced neuropathy in animal models exposed to paclitaxel, vincristine, or cisplatin.[

Anxiety and Sleep

The endocannabinoid system is believed to be centrally involved in the regulation of mood and the extinction of aversive memories. Animal studies have shown CBD to have anxiolytic properties. It was shown in rats that these anxiolytic properties are mediated through unknown mechanisms.[

The endocannabinoid system has also been shown to play a key role in the modulation of the sleep-waking cycle in rats.[

References:

- Adams IB, Martin BR: Cannabis: pharmacology and toxicology in animals and humans. Addiction 91 (11): 1585-614, 1996.

- Grotenhermen F, Russo E, eds.: Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Therapeutic Potential. The Haworth Press, 2002.

- National Toxicology Program: NTP toxicology and carcinogenesis studies of 1-trans-delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol (CAS No. 1972-08-3) in F344 rats and B6C3F1 mice (gavage studies). Natl Toxicol Program Tech Rep Ser 446: 1-317, 1996.

- Bifulco M, Laezza C, Pisanti S, et al.: Cannabinoids and cancer: pros and cons of an antitumour strategy. Br J Pharmacol 148 (2): 123-35, 2006.

- Sánchez C, de Ceballos ML, Gomez del Pulgar T, et al.: Inhibition of glioma growth in vivo by selective activation of the CB(2) cannabinoid receptor. Cancer Res 61 (15): 5784-9, 2001.

- McKallip RJ, Lombard C, Fisher M, et al.: Targeting CB2 cannabinoid receptors as a novel therapy to treat malignant lymphoblastic disease. Blood 100 (2): 627-34, 2002.

- Casanova ML, Blázquez C, Martínez-Palacio J, et al.: Inhibition of skin tumor growth and angiogenesis in vivo by activation of cannabinoid receptors. J Clin Invest 111 (1): 43-50, 2003.

- Blázquez C, González-Feria L, Alvarez L, et al.: Cannabinoids inhibit the vascular endothelial growth factor pathway in gliomas. Cancer Res 64 (16): 5617-23, 2004.

- Guzmán M: Cannabinoids: potential anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer 3 (10): 745-55, 2003.

- Blázquez C, Casanova ML, Planas A, et al.: Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis by cannabinoids. FASEB J 17 (3): 529-31, 2003.

- Vaccani A, Massi P, Colombo A, et al.: Cannabidiol inhibits human glioma cell migration through a cannabinoid receptor-independent mechanism. Br J Pharmacol 144 (8): 1032-6, 2005.

- Ramer R, Bublitz K, Freimuth N, et al.: Cannabidiol inhibits lung cancer cell invasion and metastasis via intercellular adhesion molecule-1. FASEB J 26 (4): 1535-48, 2012.

- Velasco G, Sánchez C, Guzmán M: Towards the use of cannabinoids as antitumour agents. Nat Rev Cancer 12 (6): 436-44, 2012.

- Cridge BJ, Rosengren RJ: Critical appraisal of the potential use of cannabinoids in cancer management. Cancer Manag Res 5: 301-13, 2013.

- Vara D, Salazar M, Olea-Herrero N, et al.: Anti-tumoral action of cannabinoids on hepatocellular carcinoma: role of AMPK-dependent activation of autophagy. Cell Death Differ 18 (7): 1099-111, 2011.

- Preet A, Qamri Z, Nasser MW, et al.: Cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2, as novel targets for inhibition of non-small cell lung cancer growth and metastasis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 4 (1): 65-75, 2011.

- Nasser MW, Qamri Z, Deol YS, et al.: Crosstalk between chemokine receptor CXCR4 and cannabinoid receptor CB2 in modulating breast cancer growth and invasion. PLoS One 6 (9): e23901, 2011.

- Shrivastava A, Kuzontkoski PM, Groopman JE, et al.: Cannabidiol induces programmed cell death in breast cancer cells by coordinating the cross-talk between apoptosis and autophagy. Mol Cancer Ther 10 (7): 1161-72, 2011.

- Caffarel MM, Andradas C, Mira E, et al.: Cannabinoids reduce ErbB2-driven breast cancer progression through Akt inhibition. Mol Cancer 9: 196, 2010.

- McAllister SD, Murase R, Christian RT, et al.: Pathways mediating the effects of cannabidiol on the reduction of breast cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 129 (1): 37-47, 2011.

- Aviello G, Romano B, Borrelli F, et al.: Chemopreventive effect of the non-psychotropic phytocannabinoid cannabidiol on experimental colon cancer. J Mol Med (Berl) 90 (8): 925-34, 2012.

- Romano B, Borrelli F, Pagano E, et al.: Inhibition of colon carcinogenesis by a standardized Cannabis sativa extract with high content of cannabidiol. Phytomedicine 21 (5): 631-9, 2014.

- Preet A, Ganju RK, Groopman JE: Delta9-Tetrahydrocannabinol inhibits epithelial growth factor-induced lung cancer cell migration in vitro as well as its growth and metastasis in vivo. Oncogene 27 (3): 339-46, 2008.

- Zhu LX, Sharma S, Stolina M, et al.: Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol inhibits antitumor immunity by a CB2 receptor-mediated, cytokine-dependent pathway. J Immunol 165 (1): 373-80, 2000.

- McKallip RJ, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti PS: Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol enhances breast cancer growth and metastasis by suppression of the antitumor immune response. J Immunol 174 (6): 3281-9, 2005.

- Massa F, Marsicano G, Hermann H, et al.: The endogenous cannabinoid system protects against colonic inflammation. J Clin Invest 113 (8): 1202-9, 2004.

- Patsos HA, Hicks DJ, Greenhough A, et al.: Cannabinoids and cancer: potential for colorectal cancer therapy. Biochem Soc Trans 33 (Pt 4): 712-4, 2005.

- Liu WM, Fowler DW, Dalgleish AG: Cannabis-derived substances in cancer therapy--an emerging anti-inflammatory role for the cannabinoids. Curr Clin Pharmacol 5 (4): 281-7, 2010.

- Malfitano AM, Ciaglia E, Gangemi G, et al.: Update on the endocannabinoid system as an anticancer target. Expert Opin Ther Targets 15 (3): 297-308, 2011.

- Sarfaraz S, Adhami VM, Syed DN, et al.: Cannabinoids for cancer treatment: progress and promise. Cancer Res 68 (2): 339-42, 2008.

- Nabissi M, Morelli MB, Santoni M, et al.: Triggering of the TRPV2 channel by cannabidiol sensitizes glioblastoma cells to cytotoxic chemotherapeutic agents. Carcinogenesis 34 (1): 48-57, 2013.

- Marcu JP, Christian RT, Lau D, et al.: Cannabidiol enhances the inhibitory effects of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol on human glioblastoma cell proliferation and survival. Mol Cancer Ther 9 (1): 180-9, 2010.

- Torres S, Lorente M, Rodríguez-Fornés F, et al.: A combined preclinical therapy of cannabinoids and temozolomide against glioma. Mol Cancer Ther 10 (1): 90-103, 2011.

- Rocha FC, Dos Santos Júnior JG, Stefano SC, et al.: Systematic review of the literature on clinical and experimental trials on the antitumor effects of cannabinoids in gliomas. J Neurooncol 116 (1): 11-24, 2014.

- Pacher P, Bátkai S, Kunos G: The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev 58 (3): 389-462, 2006.

- Darmani NA: Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol and synthetic cannabinoids prevent emesis produced by the cannabinoid CB(1) receptor antagonist/inverse agonist SR 141716A. Neuropsychopharmacology 24 (2): 198-203, 2001.

- Darmani NA: Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol differentially suppresses cisplatin-induced emesis and indices of motor function via cannabinoid CB(1) receptors in the least shrew. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 69 (1-2): 239-49, 2001 May-Jun.

- Parker LA, Kwiatkowska M, Burton P, et al.: Effect of cannabinoids on lithium-induced vomiting in the Suncus murinus (house musk shrew). Psychopharmacology (Berl) 171 (2): 156-61, 2004.

- Mechoulam R, Berry EM, Avraham Y, et al.: Endocannabinoids, feeding and suckling--from our perspective. Int J Obes (Lond) 30 (Suppl 1): S24-8, 2006.

- Fride E, Bregman T, Kirkham TC: Endocannabinoids and food intake: newborn suckling and appetite regulation in adulthood. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 230 (4): 225-34, 2005.

- Baker D, Pryce G, Giovannoni G, et al.: The therapeutic potential of cannabis. Lancet Neurol 2 (5): 291-8, 2003.

- Walker JM, Hohmann AG, Martin WJ, et al.: The neurobiology of cannabinoid analgesia. Life Sci 65 (6-7): 665-73, 1999.

- Meng ID, Manning BH, Martin WJ, et al.: An analgesia circuit activated by cannabinoids. Nature 395 (6700): 381-3, 1998.

- Walker JM, Huang SM, Strangman NM, et al.: Pain modulation by release of the endogenous cannabinoid anandamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96 (21): 12198-203, 1999.

- Facci L, Dal Toso R, Romanello S, et al.: Mast cells express a peripheral cannabinoid receptor with differential sensitivity to anandamide and palmitoylethanolamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92 (8): 3376-80, 1995.

- Ibrahim MM, Porreca F, Lai J, et al.: CB2 cannabinoid receptor activation produces antinociception by stimulating peripheral release of endogenous opioids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102 (8): 3093-8, 2005.

- Richardson JD, Kilo S, Hargreaves KM: Cannabinoids reduce hyperalgesia and inflammation via interaction with peripheral CB1 receptors. Pain 75 (1): 111-9, 1998.

- Khasabova IA, Gielissen J, Chandiramani A, et al.: CB1 and CB2 receptor agonists promote analgesia through synergy in a murine model of tumor pain. Behav Pharmacol 22 (5-6): 607-16, 2011.

- Ward SJ, McAllister SD, Kawamura R, et al.: Cannabidiol inhibits paclitaxel-induced neuropathic pain through 5-HT(1A) receptors without diminishing nervous system function or chemotherapy efficacy. Br J Pharmacol 171 (3): 636-45, 2014.

- Rahn EJ, Makriyannis A, Hohmann AG: Activation of cannabinoid CB1 and CB2 receptors suppresses neuropathic nociception evoked by the chemotherapeutic agent vincristine in rats. Br J Pharmacol 152 (5): 765-77, 2007.

- Khasabova IA, Khasabov S, Paz J, et al.: Cannabinoid type-1 receptor reduces pain and neurotoxicity produced by chemotherapy. J Neurosci 32 (20): 7091-101, 2012.

- Campos AC, Guimarães FS: Involvement of 5HT1A receptors in the anxiolytic-like effects of cannabidiol injected into the dorsolateral periaqueductal gray of rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 199 (2): 223-30, 2008.

- Crippa JA, Zuardi AW, Hallak JE: [Therapeutical use of the cannabinoids in psychiatry]. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 32 (Suppl 1): S56-66, 2010.

- Guimarães FS, Chiaretti TM, Graeff FG, et al.: Antianxiety effect of cannabidiol in the elevated plus-maze. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 100 (4): 558-9, 1990.

- Méndez-Díaz M, Caynas-Rojas S, Arteaga Santacruz V, et al.: Entopeduncular nucleus endocannabinoid system modulates sleep-waking cycle and mood in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 107: 29-35, 2013.

- Pava MJ, den Hartog CR, Blanco-Centurion C, et al.: Endocannabinoid modulation of cortical up-states and NREM sleep. PLoS One 9 (2): e88672, 2014.

Human / Clinical Studies

CannabisPharmacology

When oral Cannabis is ingested, there is a low (6%–20%) and variable oral bioavailability.[

Cannabinoids are known to interact with the hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme system.[

Highly concentrated THC or cannabidiol (CBD) oil extracts are illegally promoted as potential cancer cures.[

Additionally, multiple reliability and quality concerns have been raised about Cannabis analytical labs, alleging the inflation of cannabinoids content in different Cannabis products. One study showed major inconsistencies in reported THC content because of an insufficient stabilization of sample preparation and testing methods.[

Cancer Risk

A number of studies have yielded conflicting evidence regarding the risks of various cancers associated with Cannabis smoking.

A pooled analysis of three case-cohort studies of men in northwestern Africa (430 cases and 778 controls) showed a significantly increased risk of lung cancer among tobacco smokers who also inhaled Cannabis.[

A large, retrospective cohort study of 64,855 men aged 15 to 49 years from the United States found that Cannabis use was not associated with tobacco-related cancers and a number of other common malignancies. However, the study did find that, among nonsmokers of tobacco, ever having used Cannabis was associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer.[

A population-based case-control study of 611 patients with lung cancer revealed that chronic low Cannabis exposure was not associated with an increased risk of lung cancer or other upper aerodigestive tract cancers. The study also found no positive associations with any cancer type (oral, pharyngeal, laryngeal, lung, or esophageal) when adjusting for several confounders, including cigarette smoking.[

A systematic review of 19 studies evaluating premalignant or malignant lung lesions in people 18 years or older who inhaled Cannabis concluded that observational studies failed to demonstrate a statistically significant association between Cannabis inhalation and lung cancer after adjusting for tobacco use.[

Epidemiological studies examining one association of Cannabis use with head and neck squamous cell carcinomas have also been inconsistent in their findings. A pooled analysis of nine case-control studies from the U.S./Latin American International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology (INHANCE) Consortium included information from 1,921 oropharyngeal cancer cases, 356 tongue cancer cases, and 7,639 controls. The study found that Cannabis smokers had an elevated risk of oropharyngeal cancers and a reduced risk of tongue cancer compared with those who never smoked Cannabis. These study results both reflect the inconsistent effects of cannabinoids on cancer incidence noted in previous studies and suggest that more research is needed to understand the potential role of human papillomavirus infection.[

Stimulated by the hypothesis that chronic marijuana use produces adverse effects on the human endocrine and reproductive systems, the association between Cannabis use and incidence of testicular germ cell tumors (TGCTs) has been examined.[

An analysis of 84,170 participants in the California Men's Health Study was performed to investigate the association between Cannabis use and the incidence of bladder cancer. During 16 years of follow-up, 89 Cannabis users (0.3%) developed bladder cancer compared with 190 (0.4%) of the men who did not report Cannabis use (P < .001). After adjusting for age, race, ethnicity, and body mass index, Cannabis use was associated with a 45% reduction in bladder cancer incidence (hazard ratio, 0.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.33–1.00).[

A comprehensive Health Canada monograph on marijuana concluded that while there are many cellular and molecular studies that provide strong evidence that inhaled marijuana is carcinogenic, the epidemiological evidence of a link between marijuana use and cancer is still inconclusive.[

Patterns ofCannabisUse Among Cancer Patients

A cross-sectional survey of patients with cancer seen at the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance was conducted over a 6-week period between 2015 and 2016.[

Data from 2,970 Israeli patients with cancer who used government-issued Cannabis were collected over a 6-month period to assess for improvement in baseline symptoms.[

- Nausea and vomiting (91.0%).

- Sleep disorders (87.5%).

- Restlessness (87.5%).

- Anxiety and depression (84.2%).

- Pruritus (82.1%).

- Headaches (81.4%).

Before treatment initiation, 52.9% of patients reported pain scores in the 8 to 10 range, while only 4.6% of patients reported this intensity at the 6-month assessment time point. It is difficult to assess from the observational data if the improvements were caused by the Cannabis or the cancer treatment.[

Forty-two percent of women (257 of 612) with a diagnosis of breast cancer within the past 5 years who participated in an anonymous online survey reported using Cannabis for the relief of symptoms, particularly pain (78%), insomnia (70%), anxiety (57%), stress (51%), and nausea and vomiting (46%).[

Patients with cancer turn to medical Cannabis use even in states where it has not been legalized. Researchers from the Medical University of South Carolina conducted a survey study that explored the prevalence, patterns, and motivations behind Cannabis use among patients with cancer and survivors in a state without legal access to Cannabis as of 2023.[

Cancer Treatment

No ongoing clinical trials of Cannabis as a treatment for cancer in humans were identified in a PubMed search. The first published trial of any cannabinoid in patients with cancer was a small pilot study of intratumoral injection of delta-9-THC in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme, which demonstrated no significant clinical benefit.[

In a 2016 consecutive case series study, nine patients with varying stages of brain tumors, including six with glioblastoma multiforme, received CBD 200 mg twice daily in addition to surgical excision and chemoradiation.[

Another Israeli group postulated that the anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of CBD might make it a valuable adjunct in the treatment of acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in patients who have undergone allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant. The authors investigated CBD 300 mg/d in addition to standard GVHD prophylaxis in 48 adult patients who had undergone a transplant, predominantly for acute leukemia or myelodysplastic syndrome (NCT01385124 and NCT01596075).[

Clinical data regarding Cannabis as an anticancer agent in pediatric use are limited to a few case reports.[

A review of medical literature shows evidence of a growing interest in research of the use of Cannabis in cancer management.[

Antiemetic Effect

Cannabinoids

Despite advances in pharmacological and nonpharmacological management, nausea and vomiting (N/V) remain distressing side effects for patients with cancer and their families. Dronabinol, a synthetically produced delta-9-THC, was approved in the United States in 1986 as an antiemetic to be used in cancer chemotherapy. Nabilone, a synthetic derivative of delta-9-THC, was first approved in Canada in 1982 and is now also available in the United States.[

One systematic review studied 30 randomized comparisons of delta-9-THC preparations with placebo or other antiemetics from which data on efficacy and harm were available.[

Another analysis of 15 controlled studies compared nabilone with placebo or available antiemetic drugs.[

A Cochrane meta-analysis of 23 RCTs reviewed studies conducted between 1975 and 1991 that investigated dronabinol or nabilone, either as monotherapy or as an adjunct to the conventional dopamine antagonists that were the standard antiemetics at that time.[

At least 50% of patients who receive moderately emetogenic chemotherapy may experience delayed chemotherapy-induced N/V. Although selective neurokinin 1 antagonists that inhibit substance P have been approved for delayed N/V, a study was conducted before their availability to assess dronabinol, ondansetron, or their combination in preventing delayed-onset chemotherapy-induced N/V.[

For more information, see the

Cannabis

Three trials have evaluated the efficacy of inhaled Cannabis in chemotherapy-induced N/V.[

Newer antiemetics (e.g., 5-HT3 receptor antagonists) have not been directly compared with Cannabis or cannabinoids in patients with cancer. However, the Cannabis-extract oromucosal spray, nabiximols, formulated with 1:1 THC:CBD was shown in a small pilot randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded clinical trial in Spain to treat chemotherapy-related N/V.[

A phase II/III Australian/New Zealand trial included patients with a solid tumor or hematological malignancy of any stage (n = 147). Patients received a THC:CBD capsule or placebo on days -1 to 5 for the secondary prevention of refractory chemotherapy-induced N/V in combination with guideline recommended antiemetics for chemotherapy of moderate or high emetogenic risk.[

ASCO antiemetic guidelines updated in 2020 state that evidence remains insufficient to recommend medical marijuana for either the prevention or treatment of N/V in patients with cancer who receive chemotherapy or radiation therapy.[

Appetite Stimulation

Patients with cancer may experience anorexia, early satiety, weight loss, and cachexia. Such patients face not only the disfigurement associated with wasting but also cannot engage in the social interaction of meals.

Cannabinoids

Four controlled trials have assessed the effect of oral THC on measures of appetite, food appreciation, calorie intake, and weight loss in patients with advanced malignancies. Three relatively small, placebo-controlled trials (N = 52; N = 46; N = 65) each found that oral THC produced improvements in one or more of these outcomes.[

Cannabis

In trials conducted in the 1980s that involved healthy control subjects, inhaling Cannabis led to an increase in caloric intake, mainly in the form of between-meal snacks, with increased intakes of fatty and sweet foods.[

Despite patients' great interest in oral preparations of Cannabis to improve appetite, there is only one trial of Cannabis extract used for appetite stimulation. In an RCT, researchers compared the safety and effectiveness of orally administered Cannabis extract (2.5 mg THC and 1 mg CBD), THC (2.5 mg), or placebo for the treatment of cancer-related anorexia-cachexia. A total of 243 patients with advanced cancer received treatment twice daily for 6 weeks. While all extracts were well tolerated, no differences were observed in patients' appetite or quality of life among the three groups at this dose level and duration of intervention.[

No published studies have explored the effect of inhaled Cannabis on appetite in patients with cancer.

Analgesia

Cannabinoids

Pain management improves a patient's quality of life throughout all stages of cancer. Through the study of cannabinoid receptors, endocannabinoids, and synthetic agonists and antagonists, the mechanisms of cannabinoid-induced analgesia have been analyzed.[

Cancer pain results from inflammation, invasion of bone or other pain-sensitive structures, or nerve injury. When cancer pain is severe and persistent, it is often resistant to treatment with opioids.

Two studies examined the effects of oral delta-9-THC on cancer pain. The first, a double-blind, placebo-controlled study involving ten patients, measured both pain intensity and pain relief.[

In a follow-up, single-dose study involving 36 patients, 10 mg of delta-9-THC produced analgesic effects during a 7-hour observation period that were comparable to 60 mg doses of codeine, and 20 mg doses of delta-9-THC induced effects equivalent to 120 mg doses of codeine.[

Another study examined the effects of a plant extract with controlled cannabinoid content in an oromucosal spray. In a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, the THC:CBD nabiximols extract and THC extract alone were compared in the analgesic management of patients with advanced cancer and with moderate-to-severe cancer-related pain. Patients were assigned to one of three treatment groups: THC:CBD extract, THC extract, or placebo. The researchers concluded that the THC:CBD extract was efficacious for pain relief in patients with advanced cancer whose pain was not fully relieved by strong opioids.[

An observational study assessed the effectiveness of nabilone in patients with advanced cancer who were experiencing pain and other symptoms (anorexia, depression, and anxiety). The researchers reported that patients who used nabilone experienced improved management of pain, nausea, anxiety, and distress when compared with untreated patients. Nabilone was also associated with a decreased use of opioids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin, dexamethasone, metoclopramide, and ondansetron.[

Cannabis

Animal studies have suggested a synergistic analgesic effect when cannabinoids are combined with opioids. The results from one pharmacokinetic interaction study have been reported. In this study, 21 patients with chronic pain were administered vaporized Cannabis along with sustained-release morphine or oxycodone for 5 days.[

Patients with cancer may experience neuropathic pain, especially if treated with platinum-based chemotherapy or taxanes. Two RCTs of inhaled Cannabis in patients with peripheral neuropathy or neuropathic pain of various etiologies found that pain was reduced in patients who received inhaled Cannabis, compared with those who received placebo.[

A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover, pilot study of nabiximols in 16 patients with chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain showed no significant difference between the treatment and placebo groups. A responder analysis, however, demonstrated that five patients reported a reduction in their pain of at least 2 points on an 11-point scale, suggesting that a larger follow-up study may be warranted.[

One real-world randomized controlled trial explored Cannabis use in patients with advanced cancer who received care in a community oncology practice setting (148 screened; 30 randomly assigned; 18 analyzed).[

Anxiety and Sleep

Cannabinoids

In a small pilot study of analgesia involving ten patients with cancer pain, secondary measures showed that 15 mg and 20 mg doses of the cannabinoid delta-9-THC were associated with anxiolytic effects.[

A small placebo-controlled study of dronabinol in patients with cancer with altered chemosensory perception also noted increased quality of sleep and relaxation in THC-treated patients.[

Cannabis

Patients often experience mood elevation after exposure to Cannabis, depending on their previous experience. In a five-patient case series of inhaled Cannabis that examined analgesic effects in chronic pain, it was reported that patients who self-administered Cannabis had improved mood, improved sense of well-being, and less anxiety.[

Another common effect of Cannabis is sleepiness. A small placebo-controlled study of dronabinol in patients with cancer with altered chemosensory perception also noted increased quality of sleep and relaxation in THC-treated patients.[

Seventy-four patients with newly diagnosed head and neck cancer self-described as current Cannabis users were matched to 74 nonusers in a Canadian study investigating quality of life using the EuroQol-5D and Edmonton Symptom Assessment System instruments.[

A single center, phase II, double-blind study of two ratios (1:1 [THC:CBD] and 4:1 [THC:CBD]) of an oral medical Cannabis oil enrolled patients with recurrent or inoperable high-grade glioma. Investigators assessed the side effects and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Brain (FACT-Br) at baseline and 12 weeks as a primary outcome.[

Symptom Management With Cannabidiol

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (n = 144) assessed the impact of oral cannabidiol oil (50–200 mg three times a day) on the total symptom distress score (TSDS), a measure of overall cancer symptom burden.[

Pediatric Population and Cannabis and Cannabinoid Medicinal Use

A growing number of pediatric patients are seeking symptom relief with Cannabis or cannabinoid treatment, although studies are limited.[

A retrospective study from Israel of 50 pediatric oncology patients who were prescribed medicinal Cannabis over an 8-year period reported that the most common indications included the following:[

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Depressed mood.

- Sleep disturbances.

- Poor appetite and weight loss.

- Pain.

Most of the patients (n = 30) received Cannabis in the form of oral oil drops, with some of the older children inhaling vaporized Cannabis or combining inhalation with oral oils. Structured interviews with the parents, and their child when appropriate, revealed that 40 participants (80%) reported a high level of general satisfaction with the use of Cannabis with infrequent short-term side effects.[

Clinical Studies ofCannabisand Cannabinoids

| Reference | Trial Design | Condition or Cancer Type | Treatment Groups (Enrolled; Treated; Placebo or No Treatment Control)b | Resultsc | Concurrent TherapyUsedd | Level of Evidence Scoree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT3 = 5-hydroxytryptamine 3; CINV = chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting; N/V = nausea and vomiting; RCT = randomized controlled trial. | ||||||

| a For additional information and definition of terms, see text and the |

||||||

| b Number of patients treated plus number of patient controls may not equal number of patients enrolled; number of patients enrolled equals number of patients initially recruited/considered by the researchers who conducted a study; number of patients treated equals number of enrolled patients who were given the treatment being studied AND for whom results were reported. | ||||||

| c Strongest evidence reported that the treatment under study has activity or otherwise improves the well-being of patients with cancer. | ||||||

| d Concurrent therapy for symptoms treated (not cancer). | ||||||

| e For information aboutlevels of evidenceanalysis and scores, see |

||||||

| [ |

RCT | High-grade gliomas | 88; 45 (1:1), 43 (4:1); None | No difference in the primary end point | Dexamethasone, temozolomide,bevacizumab,lomustine | 1iC |

| [ |

RCT | CINV | 8; 8; None | No antiemetic effect reported | No | 1iC |

| [ |

RCT | CINV | 15; 15; None | Decreased N/V | No | 1iiC |

| [ |

Pilot RCT | CINV | 16; 7; 9 | Decreased delayed N/V | 5-HT3 receptor antagonists | 1iC |

| [ |

Nonrandomized trial | Chronic pain | 21;10 (morphine), 11 (oxycodone); None | Decreased pain | Yes, morphine, oxycodone | 2C |

| [ |

Prospective cohort study | Anxiety, pain, depression, loss of appetite | 148; 74; 74 | Decreased pain, anxiety, depression, increased appetite | Unknown | 2C |

| Reference | Trial Design | Condition or Cancer Type | Treatment Groups (Enrolled; Treated; Placebo or No Treatment Control)b | Resultsc | Concurrent Therapy Usedd | Level of Evidence Scoree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBD = cannabidiol; No. = number; NSAIDs = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; QoL = quality of life; RCT = randomized controlled trial; THC = delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. | ||||||

| a For additional information and definition of terms, see text and the |

||||||

| b Number of patients treated plus number of patient controls may not equal number of patients enrolled; number of patients enrolled equals number of patients initially recruited/considered by the researchers who conducted a study; number of patients treated equals number of enrolled patients who were given the treatment being studied AND for whom results were reported. | ||||||

| c Strongest evidence reported that the treatment under study has activity or otherwise improves the well-being of patients with cancer. | ||||||

| d Concurrent therapy for symptoms treated (not cancer). | ||||||

| e For information about levels of evidence analysis and scores, see |

||||||

| [ |

RCT | Cancer-associated anorexia | 469; dronabinol 152, megestrol acetate 159, or both 158; None | Megestrol acetate provided increased appetite and weight gain, among patients with advanced cancer compared with dronabinol alone | No | 1iC |

| [ |

Pilot RCT | Appetite | 21; 11; 10 | THC, compared with placebo, improved and enhanced taste and smell | No | 1iC |

| [ |

RCT | Cancer-related anorexia-cachexia syndrome | 243;Cannabisextract 95, THC 100; 48 | No differences in patients' appetite or QoL were found | No | 1iC |

| [ |

RCT | Appetite | 139; 72; 67 | Increase in appetite | No | 1iC |

| [ |

RCT | Anorexia | 47; 22; 25 | Increased calorie intake | No | 1iC |

| [ |

RCT | Pain | 10; 10; None | Pain relief | No | 1iC |

| [ |

RCT | Pain | 177; 60 (THC:CBD), 58 (THC); 59 | THC:CBD extract group had reduced pain | Yes, opioids | 1iC |

| [ |

RCT | Pain | 360; 269; 91 | Decreased pain in low-dose group | Yes, opioids | 1iC |

| [ |

Open-label extension | Pain | 43; 39 (THC:CBD), 4 (THC), None | Decreased pain | Yes, opioids | 2C |

| [ |

Observational study | Pain | 112; 47; 65 | Decreased pain | Yes, opioids,NSAIDs, gabapentin | 2C |

Current Clinical Trials

Use our

References:

- Adams IB, Martin BR: Cannabis: pharmacology and toxicology in animals and humans. Addiction 91 (11): 1585-614, 1996.

- Agurell S, Halldin M, Lindgren JE, et al.: Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of delta 1-tetrahydrocannabinol and other cannabinoids with emphasis on man. Pharmacol Rev 38 (1): 21-43, 1986.

- Yamamoto I, Watanabe K, Narimatsu S, et al.: Recent advances in the metabolism of cannabinoids. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 27 (8): 741-6, 1995.

- Engels FK, de Jong FA, Sparreboom A, et al.: Medicinal cannabis does not influence the clinical pharmacokinetics of irinotecan and docetaxel. Oncologist 12 (3): 291-300, 2007.

- FDA Warns Companies Marketing Unproven Products, Derived From Marijuana, That Claim to Treat or Cure Cancer [News Release]. Silver Spring, Md: Food and Drug Administration, 2017.

Available online . Last accessed January 4, 2019. - Yamaori S, Okamoto Y, Yamamoto I, et al.: Cannabidiol, a major phytocannabinoid, as a potent atypical inhibitor for CYP2D6. Drug Metab Dispos 39 (11): 2049-56, 2011.

- Jiang R, Yamaori S, Okamoto Y, et al.: Cannabidiol is a potent inhibitor of the catalytic activity of cytochrome P450 2C19. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 28 (4): 332-8, 2013.

- Azwell T, Ciotti C, Adams A: Variation among hemp (Cannabis sativus L.) analytical testing laboratories evinces regulatory and quality control issues for the industry. J Appl Res Med Aromat Plants 31: 100434, 2022.

Available online. Last accessed October 17, 2024. - Berthiller J, Straif K, Boniol M, et al.: Cannabis smoking and risk of lung cancer in men: a pooled analysis of three studies in Maghreb. J Thorac Oncol 3 (12): 1398-403, 2008.

- Sidney S, Quesenberry CP, Friedman GD, et al.: Marijuana use and cancer incidence (California, United States). Cancer Causes Control 8 (5): 722-8, 1997.

- Hashibe M, Morgenstern H, Cui Y, et al.: Marijuana use and the risk of lung and upper aerodigestive tract cancers: results of a population-based case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15 (10): 1829-34, 2006.

- Mehra R, Moore BA, Crothers K, et al.: The association between marijuana smoking and lung cancer: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 166 (13): 1359-67, 2006.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: The Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids: The Current State of Evidence and Recommendations for Research. The National Academies Press, 2017.

- Marks MA, Chaturvedi AK, Kelsey K, et al.: Association of marijuana smoking with oropharyngeal and oral tongue cancers: pooled analysis from the INHANCE consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 23 (1): 160-71, 2014.

- de Carvalho MF, Dourado MR, Fernandes IB, et al.: Head and neck cancer among marijuana users: a meta-analysis of matched case-control studies. Arch Oral Biol 60 (12): 1750-5, 2015.

- Daling JR, Doody DR, Sun X, et al.: Association of marijuana use and the incidence of testicular germ cell tumors. Cancer 115 (6): 1215-23, 2009.

- Trabert B, Sigurdson AJ, Sweeney AM, et al.: Marijuana use and testicular germ cell tumors. Cancer 117 (4): 848-53, 2011.

- Lacson JC, Carroll JD, Tuazon E, et al.: Population-based case-control study of recreational drug use and testis cancer risk confirms an association between marijuana use and nonseminoma risk. Cancer 118 (21): 5374-83, 2012.

- Callaghan RC, Allebeck P, Akre O, et al.: Cannabis Use and Incidence of Testicular Cancer: A 42-Year Follow-up of Swedish Men between 1970 and 2011. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 26 (11): 1644-1652, 2017.

- Thomas AA, Wallner LP, Quinn VP, et al.: Association between cannabis use and the risk of bladder cancer: results from the California Men's Health Study. Urology 85 (2): 388-92, 2015.

- Health Canada: Marihuana (Marijuana, Cannabis): Dried Plant for Administration by Ingestion or Other Means. Ottawa, Canada: Health Canada, 2010.

Available online . Last accessed October 18, 2017. - Pergam SA, Woodfield MC, Lee CM, et al.: Cannabis use among patients at a comprehensive cancer center in a state with legalized medicinal and recreational use. Cancer 123 (22): 4488-4497, 2017.

- Bar-Lev Schleider L, Mechoulam R, Lederman V, et al.: Prospective analysis of safety and efficacy of medical cannabis in large unselected population of patients with cancer. Eur J Intern Med 49: 37-43, 2018.

- Anderson SP, Zylla DM, McGriff DM, et al.: Impact of Medical Cannabis on Patient-Reported Symptoms for Patients With Cancer Enrolled in Minnesota's Medical Cannabis Program. J Oncol Pract 15 (4): e338-e345, 2019.

- Weiss MC, Hibbs JE, Buckley ME, et al.: A Coala-T-Cannabis Survey Study of breast cancer patients' use of cannabis before, during, and after treatment. Cancer 128 (1): 160-168, 2022.

- McClure EA, Walters KJ, Tomko RL, et al.: Cannabis use prevalence, patterns, and reasons for use among patients with cancer and survivors in a state without legal cannabis access. Support Care Cancer 31 (7): 429, 2023.

- Guzmán M, Duarte MJ, Blázquez C, et al.: A pilot clinical study of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol in patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. Br J Cancer 95 (2): 197-203, 2006.

- Velasco G, Sánchez C, Guzmán M: Towards the use of cannabinoids as antitumour agents. Nat Rev Cancer 12 (6): 436-44, 2012.

- Twelves C, Sabel M, Checketts D, et al.: A phase 1b randomised, placebo-controlled trial of nabiximols cannabinoid oromucosal spray with temozolomide in patients with recurrent glioblastoma. Br J Cancer 124 (8): 1379-1387, 2021.

- Likar R, Koestenberger M, Stultschnig M, et al.: Concomitant Treatment of Malignant Brain Tumours With CBD - A Case Series and Review of the Literature. Anticancer Res 39 (10): 5797-5801, 2019.

- Yeshurun M, Shpilberg O, Herscovici C, et al.: Cannabidiol for the Prevention of Graft-versus-Host-Disease after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: Results of a Phase II Study. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21 (10): 1770-5, 2015.

- Singh Y, Bali C: Cannabis extract treatment for terminal acute lymphoblastic leukemia with a Philadelphia chromosome mutation. Case Rep Oncol 6 (3): 585-92, 2013.

- Foroughi M, Hendson G, Sargent MA, et al.: Spontaneous regression of septum pellucidum/forniceal pilocytic astrocytomas--possible role of Cannabis inhalation. Childs Nerv Syst 27 (4): 671-9, 2011.

- Goyal S, Kubendran S, Kogan M, et al.: High expectations: The landscape of clinical trials of medical marijuana in oncology. Complement Ther Med 49: 102336, 2020.

- Sutton IR, Daeninck P: Cannabinoids in the management of intractable chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and cancer-related pain. J Support Oncol 4 (10): 531-5, 2006 Nov-Dec.

- Ahmedzai S, Carlyle DL, Calder IT, et al.: Anti-emetic efficacy and toxicity of nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, in lung cancer chemotherapy. Br J Cancer 48 (5): 657-63, 1983.

- Chan HS, Correia JA, MacLeod SM: Nabilone versus prochlorperazine for control of cancer chemotherapy-induced emesis in children: a double-blind, crossover trial. Pediatrics 79 (6): 946-52, 1987.

- Johansson R, Kilkku P, Groenroos M: A double-blind, controlled trial of nabilone vs. prochlorperazine for refractory emesis induced by cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Treat Rev 9 (Suppl B): 25-33, 1982.

- Niiranen A, Mattson K: A cross-over comparison of nabilone and prochlorperazine for emesis induced by cancer chemotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol 8 (4): 336-40, 1985.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Antiemesis. Version 1.2021. Plymouth Meeting, Pa: National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2021.

Available online with free registration . Last accessed August 26, 2021.. - Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Basch E, et al.: Antiemetics: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 38 (24): 2782-2797, 2020.

- Tramèr MR, Carroll D, Campbell FA, et al.: Cannabinoids for control of chemotherapy induced nausea and vomiting: quantitative systematic review. BMJ 323 (7303): 16-21, 2001.

- Ben Amar M: Cannabinoids in medicine: A review of their therapeutic potential. J Ethnopharmacol 105 (1-2): 1-25, 2006.

- Smith LA, Azariah F, Lavender VT, et al.: Cannabinoids for nausea and vomiting in adults with cancer receiving chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (11): CD009464, 2015.

- Meiri E, Jhangiani H, Vredenburgh JJ, et al.: Efficacy of dronabinol alone and in combination with ondansetron versus ondansetron alone for delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Curr Med Res Opin 23 (3): 533-43, 2007.

- Chang AE, Shiling DJ, Stillman RC, et al.: A prospective evaluation of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol as an antiemetic in patients receiving adriamycin and cytoxan chemotherapy. Cancer 47 (7): 1746-51, 1981.

- Chang AE, Shiling DJ, Stillman RC, et al.: Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol as an antiemetic in cancer patients receiving high-dose methotrexate. A prospective, randomized evaluation. Ann Intern Med 91 (6): 819-24, 1979.

- Levitt M, Faiman C, Hawks R, et al.: Randomized double blind comparison of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and marijuana as chemotherapy antiemetics. [Abstract] Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 3: A-C354, 91, 1984.

- Musty RE, Rossi R: Effects of smoked cannabis and oral delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol on nausea and emesis after cancer chemotherapy: a review of state clinical trials. Journal of Cannabis Therapeutics 1 (1): 29-56, 2001.

Also available online . Last accessed October 18, 2017. - Duran M, Pérez E, Abanades S, et al.: Preliminary efficacy and safety of an oromucosal standardized cannabis extract in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Br J Clin Pharmacol 70 (5): 656-63, 2010.

- Grimison P, Mersiades A, Kirby A, et al.: Oral Cannabis Extract for Secondary Prevention of Chemotherapy-Induced Nausea and Vomiting: Final Results of a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Phase II/III Trial. J Clin Oncol 42 (34): 4040-4050, 2024.

- Regelson W, Butler JR, Schulz J, et al.: Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol as an effective antidepressant and appetite-stimulating agent in advanced cancer patients. In: Braude MC, Szara S: The Pharmacology of Marihuana. Raven Press, 1976, pp 763-76.

- Brisbois TD, de Kock IH, Watanabe SM, et al.: Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol may palliate altered chemosensory perception in cancer patients: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Ann Oncol 22 (9): 2086-93, 2011.

- Turcott JG, Del Rocío Guillen Núñez M, Flores-Estrada D, et al.: The effect of nabilone on appetite, nutritional status, and quality of life in lung cancer patients: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Support Care Cancer 26 (9): 3029-3038, 2018.

- Jatoi A, Windschitl HE, Loprinzi CL, et al.: Dronabinol versus megestrol acetate versus combination therapy for cancer-associated anorexia: a North Central Cancer Treatment Group study. J Clin Oncol 20 (2): 567-73, 2002.

- Foltin RW, Brady JV, Fischman MW: Behavioral analysis of marijuana effects on food intake in humans. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 25 (3): 577-82, 1986.

- Foltin RW, Fischman MW, Byrne MF: Effects of smoked marijuana on food intake and body weight of humans living in a residential laboratory. Appetite 11 (1): 1-14, 1988.

- Strasser F, Luftner D, Possinger K, et al.: Comparison of orally administered cannabis extract and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in treating patients with cancer-related anorexia-cachexia syndrome: a multicenter, phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial from the Cannabis-In-Cachexia-Study-Group. J Clin Oncol 24 (21): 3394-400, 2006.

- Aggarwal SK: Cannabinergic pain medicine: a concise clinical primer and survey of randomized-controlled trial results. Clin J Pain 29 (2): 162-71, 2013.

- Walker JM, Hohmann AG, Martin WJ, et al.: The neurobiology of cannabinoid analgesia. Life Sci 65 (6-7): 665-73, 1999.

- Calignano A, La Rana G, Giuffrida A, et al.: Control of pain initiation by endogenous cannabinoids. Nature 394 (6690): 277-81, 1998.

- Fields HL, Meng ID: Watching the pot boil. Nat Med 4 (9): 1008-9, 1998.

- Noyes R, Brunk SF, Baram DA, et al.: Analgesic effect of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol. J Clin Pharmacol 15 (2-3): 139-43, 1975 Feb-Mar.

- Noyes R, Brunk SF, Avery DA, et al.: The analgesic properties of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and codeine. Clin Pharmacol Ther 18 (1): 84-9, 1975.

- Johnson JR, Burnell-Nugent M, Lossignol D, et al.: Multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of THC:CBD extract and THC extract in patients with intractable cancer-related pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 39 (2): 167-79, 2010.

- Portenoy RK, Ganae-Motan ED, Allende S, et al.: Nabiximols for opioid-treated cancer patients with poorly-controlled chronic pain: a randomized, placebo-controlled, graded-dose trial. J Pain 13 (5): 438-49, 2012.

- Johnson JR, Lossignol D, Burnell-Nugent M, et al.: An open-label extension study to investigate the long-term safety and tolerability of THC/CBD oromucosal spray and oromucosal THC spray in patients with terminal cancer-related pain refractory to strong opioid analgesics. J Pain Symptom Manage 46 (2): 207-18, 2013.

- Maida V, Ennis M, Irani S, et al.: Adjunctive nabilone in cancer pain and symptom management: a prospective observational study using propensity scoring. J Support Oncol 6 (3): 119-24, 2008.

- Abrams DI, Couey P, Shade SB, et al.: Cannabinoid-opioid interaction in chronic pain. Clin Pharmacol Ther 90 (6): 844-51, 2011.

- Wilsey B, Marcotte T, Deutsch R, et al.: Low-dose vaporized cannabis significantly improves neuropathic pain. J Pain 14 (2): 136-48, 2013.

- Wilsey B, Marcotte T, Tsodikov A, et al.: A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of cannabis cigarettes in neuropathic pain. J Pain 9 (6): 506-21, 2008.

- Waissengrin B, Mirelman D, Pelles S, et al.: Effect of cannabis on oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy among oncology patients: a retrospective analysis. Ther Adv Med Oncol 13: 1758835921990203, 2021.

- Lynch ME, Cesar-Rittenberg P, Hohmann AG: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover pilot trial with extension using an oral mucosal cannabinoid extract for treatment of chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 47 (1): 166-73, 2014.

- Zylla DM, Eklund J, Gilmore G, et al.: A randomized trial of medical cannabis in patients with stage IV cancers to assess feasibility, dose requirements, impact on pain and opioid use, safety, and overall patient satisfaction. Support Care Cancer 29 (12): 7471-7478, 2021.

- Noyes R, Baram DA: Cannabis analgesia. Compr Psychiatry 15 (6): 531-5, 1974 Nov-Dec.

- Zhang H, Xie M, Archibald SD, et al.: Association of Marijuana Use With Psychosocial and Quality of Life Outcomes Among Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 144 (11): 1017-1022, 2018.

- Schloss J, Lacey J, Sinclair J, et al.: A Phase 2 Randomised Clinical Trial Assessing the Tolerability of Two Different Ratios of Medicinal Cannabis in Patients With High Grade Gliomas. Front Oncol 11: 649555, 2021.

- Hardy J, Greer R, Huggett G, et al.: Phase IIb Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Dose-Escalating, Double-Blind Study of Cannabidiol Oil for the Relief of Symptoms in Advanced Cancer (MedCan1-CBD). J Clin Oncol 41 (7): 1444-1452, 2023.

- Chhabra M, Ben-Eltriki M, Paul A, et al.: Cannabinoids for symptom management in children with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer 129 (22): 3656-3670, 2023.

- Ofir R, Bar-Sela G, Weyl Ben-Arush M, et al.: Medical marijuana use for pediatric oncology patients: single institution experience. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 36 (5): 255-266, 2019.

- Oberoi S, Protudjer JLP, Rapoport A, et al.: Perspectives of pediatric oncologists and palliative care physicians on the therapeutic use of cannabis in children with cancer. Cancer Rep (Hoboken) 5 (9): e1551, 2022.

- Ananth P, Ma C, Al-Sayegh H, et al.: Provider Perspectives on Use of Medical Marijuana in Children With Cancer. Pediatrics 141 (1): , 2018.

- Beal JE, Olson R, Laubenstein L, et al.: Dronabinol as a treatment for anorexia associated with weight loss in patients with AIDS. J Pain Symptom Manage 10 (2): 89-97, 1995.

Adverse Effects

Cannabisand Cannabinoids

Because cannabinoid receptors, unlike opioid receptors, are not located in the brainstem areas controlling respiration, lethal overdoses from Cannabis and cannabinoids do not occur.[

- Tachycardia.

- Hypotension.

- Conjunctival injection.

- Bronchodilation.

- Muscle relaxation.

- Decreased gastrointestinal motility.

Although cannabinoids are considered by some to be addictive drugs, their addictive potential is considerably lower than that of other prescribed agents or substances of abuse.[

Withdrawal symptoms such as irritability, insomnia with sleep electroencephalogram disturbance, restlessness, hot flashes, and, rarely, nausea and cramping have been observed. However, these symptoms appear to be mild compared with withdrawal symptoms associated with opiates or benzodiazepines, and the symptoms usually dissipate after a few days.

Unlike other commonly used drugs, cannabinoids are stored in adipose tissue and excreted at a low rate (half-life 1–3 days), so even abrupt cessation of cannabinoid intake is not associated with rapid declines in plasma concentrations that would precipitate severe or abrupt withdrawal symptoms or drug cravings.

Cannabidiol (CBD) is an inhibitor of cytochrome P450 isoforms in vitro. Because many anticancer therapies are metabolized by these enzymes, highly concentrated CBD oils used concurrently could potentially increase the toxicity or decrease the effectiveness of these therapies.[

Since Cannabis smoke contains many of the same components as tobacco smoke, there are valid concerns about the adverse pulmonary effects of inhaled Cannabis. A longitudinal study in a noncancer population evaluated repeated measurements of pulmonary function over 20 years in 5,115 men and women whose smoking histories were known.[

Interactions With Conventional Cancer Therapies

The potential for cytochrome P450 interactions with highly concentrated oil preparations of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and/or cannabidiol is a concern.[

An Israeli retrospective observational study assessed the impact of Cannabis use during nivolumab immunotherapy.[

References:

- Adams IB, Martin BR: Cannabis: pharmacology and toxicology in animals and humans. Addiction 91 (11): 1585-614, 1996.

- Grotenhermen F, Russo E, eds.: Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Pharmacology, Toxicology, and Therapeutic Potential. The Haworth Press, 2002.

- Sutton IR, Daeninck P: Cannabinoids in the management of intractable chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and cancer-related pain. J Support Oncol 4 (10): 531-5, 2006 Nov-Dec.

- Guzmán M: Cannabinoids: potential anticancer agents. Nat Rev Cancer 3 (10): 745-55, 2003.

- Yamaori S, Okamoto Y, Yamamoto I, et al.: Cannabidiol, a major phytocannabinoid, as a potent atypical inhibitor for CYP2D6. Drug Metab Dispos 39 (11): 2049-56, 2011.

- Jiang R, Yamaori S, Okamoto Y, et al.: Cannabidiol is a potent inhibitor of the catalytic activity of cytochrome P450 2C19. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 28 (4): 332-8, 2013.

- Guedon M, Le Bozec A, Brugel M, et al.: Cannabidiol-drug interaction in cancer patients: A retrospective study in a real-life setting. Br J Clin Pharmacol 89 (7): 2322-2328, 2023.

- Pletcher MJ, Vittinghoff E, Kalhan R, et al.: Association between marijuana exposure and pulmonary function over 20 years. JAMA 307 (2): 173-81, 2012.

- Kocis PT, Vrana KE: Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol drug-drug interactions. Med Cannabis Cannabinoids 3 (1): 61-73, 2020.

- Taha T, Meiri D, Talhamy S, et al.: Cannabis Impacts Tumor Response Rate to Nivolumab in Patients with Advanced Malignancies. Oncologist 24 (4): 549-554, 2019.

- Bar-Sela G, Cohen I, Campisi-Pinto S, et al.: Cannabis Consumption Used by Cancer Patients during Immunotherapy Correlates with Poor Clinical Outcome. Cancers (Basel) 12 (9): , 2020.

Summary of the Evidence for Cannabis and Cannabinoids

To assist readers in evaluating the results of human studies of integrative, alternative, and complementary therapies for people with cancer, the strength of the evidence (i.e., the levels of evidence) associated with each type of treatment is provided whenever possible. To qualify for a level of evidence analysis, a study must:

- Be published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

- Report on therapeutic outcome or outcomes, such as tumor response, improvement in survival, or measured improvement in quality of life.

- Describe clinical findings in sufficient detail for a meaningful evaluation to be made.

Separate levels of evidence scores are assigned to qualifying human studies on the basis of statistical strength of the study design and scientific strength of the treatment outcomes (i.e., end points) measured. The resulting two scores are then combined to produce an overall score. For an explanation of possible scores and additional information about levels of evidence analysis of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) treatments for people with cancer, see

Cannabinoids

| Several controlled clinical trials have been performed, and meta-analyses of these support a beneficial effect of cannabinoids (dronabinol and nabilone) on chemotherapy -induced nausea and vomiting (N/V) compared with placebo. Both dronabinol and nabilone are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the prevention or treatment of chemotherapy-induced N/V in patients with cancer but not for other symptom management. |

Cannabis

- There have been ten clinical trials on the use of inhaled Cannabis in cancer patients that can be divided into two groups. In one group, four small studies assessed antiemetic activity, but each explored a different patient population and chemotherapy regimen. One study demonstrated no effect, the second study showed a positive effect versus placebo, and the report of the third study did not provide enough information to characterize the overall outcome as positive or neutral. Consequently, there are insufficient data to provide an overall level of evidence assessment for the use of Cannabis for chemotherapy-induced N/V. Apparently, there are no published controlled clinical trials on the use of inhaled Cannabis for other cancer-related or cancer treatment–related symptoms.

- An increasing number of trials are evaluating the oromucosal administration of Cannabis plant extract with fixed concentrations of cannabinoid components, with national drug regulatory agencies in Canada and in some European countries that issue approval for cancer pain.

- At present, there is insufficient evidence to recommend inhaling Cannabis as a treatment for cancer-related symptoms or cancer treatment–related symptoms or cancer treatment-related side effects; however, additional research is needed.

Latest Updates to This Summary (02 / 21 / 2025)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Added

Revised

This summary is written and maintained by the

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the use of Cannabis and cannabinoids in the treatment of people with cancer. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Integrative, Alternative, and Complementary Therapies Editorial Board uses a

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Integrative, Alternative, and Complementary Therapies Editorial Board. PDQ Cannabis and Cannabinoids. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at:

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our

Last Revised: 2025-02-21

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the

Healthwise, Healthwise for every health decision, and the Healthwise logo are trademarks of Ignite Healthwise, LLC.

Page Footer

I want to...

Audiences

Secure Member Sites

The Cigna Group Information

Disclaimer

Individual and family medical and dental insurance plans are insured by Cigna Health and Life Insurance Company (CHLIC), Cigna HealthCare of Arizona, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Illinois, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Georgia, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of North Carolina, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of South Carolina, Inc., and Cigna HealthCare of Texas, Inc. Group health insurance and health benefit plans are insured or administered by CHLIC, Connecticut General Life Insurance Company (CGLIC), or their affiliates (see

All insurance policies and group benefit plans contain exclusions and limitations. For availability, costs and complete details of coverage, contact a licensed agent or Cigna sales representative. This website is not intended for residents of New Mexico.