Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage

Plans through your employer

Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

Learn

Living or working abroad?

Cervical Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

General Information About Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is relatively rare but is diagnosed most frequently in women aged 35 to 44 years.[

Incidence and Mortality

Estimated new cases and deaths from cervical (uterine cervix) cancer in the United States in 2025:[

- New cases: 13,360.

- Deaths: 4,320.

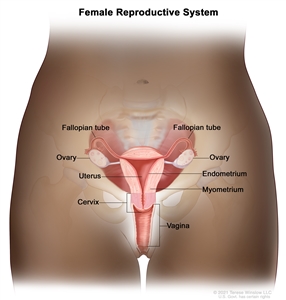

Anatomy

The uterine cervix is contiguous with the uterine body, and it acts as the opening to the body of the uterus. The uterine cervix is a cylindrical, fibrous organ that is an average of 3 to 4 cm in length. The portio of the cervix is visible on vaginal inspection. The opening of the cervix is termed the external os. The os is the beginning of the endocervical canal, which forms the inner aspect of the cervix. At the upper aspect of the endocervical canal is the internal os, a narrowing of the endocervical canal. The narrowing marks the transition from the cervix to the uterine body. The endocervical canal beyond the internal os is termed the endometrial canal.

The cervix is lined by two types of epithelial cells: squamous cells at the outer aspect and columnar, glandular cells along the inner canal. The transition between squamous cells and columnar cells is an area termed the squamocolumnar junction. Most precancerous and cancerous changes arise in this zone.

Pathogenesis

Cervical carcinoma begins at the squamocolumnar junction. It can involve the outer squamous cells, inner glandular cells, or both. The precursor lesion is dysplasia: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or adenocarcinoma in situ, which can subsequently become invasive cancer. This process can be quite slow. Longitudinal studies have shown that in patients with untreated in situ cervical cancer, 30% to 70% will develop invasive carcinoma over a period of 10 to 12 years. However, in about 10% of patients, lesions can progress from in situ to invasive in less than 1 year. As it becomes invasive, the tumor breaks through the basement membrane and invades the cervical stroma. Extension of the tumor in the cervix may ultimately manifest as ulceration, exophytic tumor, or extensive infiltration of underlying tissue, including the bladder or rectum.

Risk Factors

Increasing age is the most important risk factor for most cancers. The primary risk factor for cervical cancer is human papillomavirus (HPV) infection.[

Other risk factors for cervical cancer include the following:

- High parity and HPV infection.[

8 ] - Smoking cigarettes and HPV infection.[

9 ] - Long-term use of oral contraceptives and HPV infection.[

10 ,11 ] - Immunosuppression.[

12 ,13 ] - Having first sexual encounter at a young age.[

14 ] - High number of sexual partners.[

14 ] - Exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES) in utero.[

15 ]

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection

HPV infection is a necessary step in the development of virtually all precancerous and cancerous lesions. Epidemiological studies convincingly demonstrate that the major risk factor for development of preinvasive or invasive carcinoma of the cervix is HPV infection, far outweighing other known risk factors.

More than 6 million women in the United States are estimated to be infected with HPV. Transient HPV infection is common, particularly in young women,[

The strain of HPV infection is also important in conferring risk. Multiple subtypes of HPV infect humans; subtypes 16 and 18 have been most closely associated with high-grade dysplasia and cancer. Studies suggest that acute infection with HPV types 16 and 18 conferred an 11-fold to 16.9-fold risk of rapid development of high-grade CIN.[

There are two commercially available vaccines that target anogenital-related strains of HPV. The vaccines are directed toward HPV-naïve adolescents and young adults. Although penetration of the vaccine has been moderate, significant decreases in HPV-related diseases have been documented.[

Clinical Features

Early cervical cancer may not cause noticeable signs or symptoms.

Possible signs and symptoms of cervical cancer include:

- Vaginal bleeding.

- Unusual vaginal discharge.

- Pelvic pain.

- Dyspareunia.

- Postcoital bleeding.

Diagnosis

The following procedures may be used to diagnose cervical cancer:

- History and physical examination.

- Pelvic examination.

- Cervical cytology (Pap smear).

- HPV test.

- Endocervical curettage.

- Colposcopy.

- Biopsy.

HPV testing

Cervical cytology (Pap smear) has been the mainstay of cervical cancer screening since its introduction. However, molecular techniques for the identification of HPV DNA are highly sensitive and specific. Current screening options include:

- Cytology alone.

- Cytology and HPV testing.

HPV testing is suggested when it is likely to successfully triage patients into low- and high-risk groups for a high-grade dysplasia or greater lesion.

HPV DNA tests are unlikely to separate patients with low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions into those who do and those who do not need further evaluation. A study of 642 women found that 83% had one or more tumorigenic HPV types when cervical cytological specimens were assayed by a sensitive (hybrid capture) technique.[

HPV DNA testing has proven useful in triaging patients with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance to colposcopy and has been integrated into current screening guidelines.[

Other studies show that patients with low-risk cytology and high-risk HPV infection with types 16, 18, and 31 are more likely to have CIN or microinvasive histopathology on biopsy.[

For women older than 30 years who are more likely to have persistent HPV infection, HPV typing can successfully triage women into high- and low-risk groups for CIN 3 or worse disease. In this age group, HPV DNA testing is more effective than cytology alone in predicting the risk of developing CIN 3 or worse.[

Prognostic Factors

The prognosis for patients with cervical cancer is markedly affected by the extent of disease at the time of diagnosis. More than 90% of cervical cancer cases can be detected early by using the Pap test and HPV testing.[

Clinical stage

Clinical stage as a prognostic factor is supplemented by several gross and microscopic pathological findings in surgically treated patients.

Evidence (clinical stage and other findings):

In a large, surgicopathological staging study of patients with clinical stage IB disease reported by the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) GOG-49, the factors that most prominently predicted lymph node metastases and a decrease in disease-free survival were capillary-lymphatic space involvement by tumor, increasing tumor size, and increasing depth of stromal invasion, with the latter being the most important and reproducible.[

In a study of 1,028 patients treated with radical surgery, survival rates correlated more consistently with tumor volume (as determined by precise volumetry of the tumor) than with clinical or histological stage.[

A multivariate analysis of prognostic variables in 626 patients with locally advanced disease (primarily stages II, III, and IV) studied by the GOG identified the following variables that were significant for progression-free interval and survival:[

- Periaortic and pelvic lymph node status.

- Tumor size.

- Patient age.

- Performance status.

- Bilateral disease.

- Clinical stage.

The study confirmed the overriding importance of positive periaortic nodes and suggested further evaluation of these nodes in locally advanced cervical cancer. The status of the pelvic nodes was important only if the periaortic nodes were negative. This was also true for tumor size.

It is controversial whether adenocarcinoma of the cervix carries a significantly worse prognosis than squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix.[

In a large series of cervical cancer patients treated by radiation therapy, the incidence of distant metastases (most frequently to the lung, abdominal cavity, liver, and gastrointestinal tract) was shown to increase as the stage of disease increased, from 3% in stage IA to 75% in stage IVA.[

GOG studies have indicated that prognostic factors vary depending on whether clinical or surgical staging is used and with different treatments. Delay in radiation delivery completion is associated with poorer progression-free survival when clinical staging is used. Stage, tumor grade, race, and age are uncertain prognostic factors in studies using chemoradiation.[

Other prognostic factors

Other prognostic factors that may affect outcome include:

- HIV status: Women with HIV have more aggressive and advanced disease and a poorer prognosis.[

51 ] - MYC overexpression: A study of patients with known invasive squamous carcinoma of the cervix found that overexpression of the MYC oncogene was associated with a poorer prognosis.[

52 ] - Number of cells in S phase: The number of cells in S phase may also have prognostic significance in early cervical carcinoma.[

53 ] - HPV-18 DNA: HPV-18 DNA is an independent adverse molecular prognostic factor. Two studies have shown a worse outcome when HPV-18 was identified in cervical cancers of patients undergoing radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy.[

54 ,55 ] - A polymorphism in the Gamma-glutamyl hydrolase enzyme, which is related to folate metabolism, has been shown to decrease response to cisplatin, and as a result is associated with poorer outcomes.[

56 ]

Follow-Up After Treatment

High-quality studies are lacking, and the optimal follow-up for patients after treatment for cervical cancer is unknown. Retrospective studies have shown that cancer recurrence is most likely within the first 2 years.[

Follow-up should be centered around a thorough history and physical examination with a careful review of symptoms. Imaging should be reserved for evaluation of a positive finding. Patients should be asked about possible warning signs, including:

- Abdominal pain.

- Back pain.

- Painful or swollen leg.

- Problems with urination.

- Cough.

- Fatigue.

The follow-up examination should also screen for possible complications of previous treatment because of the multiple modalities (surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation) that patients often undergo during their treatment.

References:

- National Cancer Institute: SEER Cancer Stat Facts: Cervical Cancer. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute.

Available online . Last accessed February 28, 2025. - Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al.: Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 74 (3): 229-263, 2024.

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. American Cancer Society, 2025.

Available online . Last accessed January 16, 2025. - IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Human papillomaviruses. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 100 (Pt B), 255-296, 2012.

Available online . Last accessed January 31, 2025. - Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, et al.: Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet 370 (9590): 890-907, 2007.

- Trottier H, Franco EL: The epidemiology of genital human papillomavirus infection. Vaccine 24 (Suppl 1): S1-15, 2006.

- Ault KA: Epidemiology and natural history of human papillomavirus infections in the female genital tract. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2006 (Suppl): 40470, 2006.

- Muñoz N, Franceschi S, Bosetti C, et al.: Role of parity and human papillomavirus in cervical cancer: the IARC multicentric case-control study. Lancet 359 (9312): 1093-101, 2002.

- Plummer M, Herrero R, Franceschi S, et al.: Smoking and cervical cancer: pooled analysis of the IARC multi-centric case--control study. Cancer Causes Control 14 (9): 805-14, 2003.

- Moreno V, Bosch FX, Muñoz N, et al.: Effect of oral contraceptives on risk of cervical cancer in women with human papillomavirus infection: the IARC multicentric case-control study. Lancet 359 (9312): 1085-92, 2002.

- Appleby P, Beral V, Berrington de González A, et al.: Cervical cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data for 16,573 women with cervical cancer and 35,509 women without cervical cancer from 24 epidemiological studies. Lancet 370 (9599): 1609-21, 2007.

- Abraham AG, D'Souza G, Jing Y, et al.: Invasive cervical cancer risk among HIV-infected women: a North American multicohort collaboration prospective study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 62 (4): 405-13, 2013.

- Grulich AE, van Leeuwen MT, Falster MO, et al.: Incidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: a meta-analysis. Lancet 370 (9581): 59-67, 2007.

- International Collaboration of Epidemiological Studies of Cervical Cancer: Cervical carcinoma and reproductive factors: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 16,563 women with cervical carcinoma and 33,542 women without cervical carcinoma from 25 epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer 119 (5): 1108-24, 2006.

- Hoover RN, Hyer M, Pfeiffer RM, et al.: Adverse health outcomes in women exposed in utero to diethylstilbestrol. N Engl J Med 365 (14): 1304-14, 2011.

- Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, et al.: Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA 297 (8): 813-9, 2007.

- Rodríguez AC, Schiffman M, Herrero R, et al.: Rapid clearance of human papillomavirus and implications for clinical focus on persistent infections. J Natl Cancer Inst 100 (7): 513-7, 2008.

- Jaisamrarn U, Castellsagué X, Garland SM, et al.: Natural history of progression of HPV infection to cervical lesion or clearance: analysis of the control arm of the large, randomised PATRICIA study. PLoS One 8 (11): e79260, 2013.

- Brisson J, Morin C, Fortier M, et al.: Risk factors for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: differences between low- and high-grade lesions. Am J Epidemiol 140 (8): 700-10, 1994.

- Koutsky LA, Holmes KK, Critchlow CW, et al.: A cohort study of the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 in relation to papillomavirus infection. N Engl J Med 327 (18): 1272-8, 1992.

- Schiffman MH, Bauer HM, Hoover RN, et al.: Epidemiologic evidence showing that human papillomavirus infection causes most cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst 85 (12): 958-64, 1993.

- Castle PE, Glass AG, Rush BB, et al.: Clinical human papillomavirus detection forecasts cervical cancer risk in women over 18 years of follow-up. J Clin Oncol 30 (25): 3044-50, 2012.

- Khan MJ, Castle PE, Lorincz AT, et al.: The elevated 10-year risk of cervical precancer and cancer in women with human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 or 18 and the possible utility of type-specific HPV testing in clinical practice. J Natl Cancer Inst 97 (14): 1072-9, 2005.

- Schlecht NF, Kulaga S, Robitaille J, et al.: Persistent human papillomavirus infection as a predictor of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. JAMA 286 (24): 3106-14, 2001.

- Muñoz N, Kjaer SK, Sigurdsson K, et al.: Impact of human papillomavirus (HPV)-6/11/16/18 vaccine on all HPV-associated genital diseases in young women. J Natl Cancer Inst 102 (5): 325-39, 2010.

- Human papillomavirus testing for triage of women with cytologic evidence of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions: baseline data from a randomized trial. The Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance/Low-Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesions Triage Study (ALTS) Group. J Natl Cancer Inst 92 (5): 397-402, 2000.

- Wright TC, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, et al.: 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol 197 (4): 346-55, 2007.

- Wright TC, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, et al.: 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ. Am J Obstet Gynecol 197 (4): 340-5, 2007.

- Tabbara S, Saleh AD, Andersen WA, et al.: The Bethesda classification for squamous intraepithelial lesions: histologic, cytologic, and viral correlates. Obstet Gynecol 79 (3): 338-46, 1992.

- Cuzick J, Terry G, Ho L, et al.: Human papillomavirus type 16 in cervical smears as predictor of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [corrected] Lancet 339 (8799): 959-60, 1992.

- Richart RM, Wright TC: Controversies in the management of low-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Cancer 71 (4 Suppl): 1413-21, 1993.

- Klaes R, Woerner SM, Ridder R, et al.: Detection of high-risk cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer by amplification of transcripts derived from integrated papillomavirus oncogenes. Cancer Res 59 (24): 6132-6, 1999.

- Katki HA, Kinney WK, Fetterman B, et al.: Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol 12 (7): 663-72, 2011.

- Naucler P, Ryd W, Törnberg S, et al.: Efficacy of HPV DNA testing with cytology triage and/or repeat HPV DNA testing in primary cervical cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst 101 (2): 88-99, 2009.

- Castle PE, Stoler MH, Wright TC, et al.: Performance of carcinogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) testing and HPV16 or HPV18 genotyping for cervical cancer screening of women aged 25 years and older: a subanalysis of the ATHENA study. Lancet Oncol 12 (9): 880-90, 2011.

- The 1988 Bethesda System for reporting cervical/vaginal cytological diagnoses. National Cancer Institute Workshop. JAMA 262 (7): 931-4, 1989.

- Delgado G, Bundy B, Zaino R, et al.: Prospective surgical-pathological study of disease-free interval in patients with stage IB squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 38 (3): 352-7, 1990.

- Zaino RJ, Ward S, Delgado G, et al.: Histopathologic predictors of the behavior of surgically treated stage IB squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer 69 (7): 1750-8, 1992.

- Burghardt E, Baltzer J, Tulusan AH, et al.: Results of surgical treatment of 1028 cervical cancers studied with volumetry. Cancer 70 (3): 648-55, 1992.

- Stehman FB, Bundy BN, DiSaia PJ, et al.: Carcinoma of the cervix treated with radiation therapy. I. A multi-variate analysis of prognostic variables in the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Cancer 67 (11): 2776-85, 1991.

- Steren A, Nguyen HN, Averette HE, et al.: Radical hysterectomy for stage IB adenocarcinoma of the cervix: the University of Miami experience. Gynecol Oncol 48 (3): 355-9, 1993.

- Park JY, Kim DY, Kim JH, et al.: Outcomes after radical hysterectomy in patients with early-stage adenocarcinoma of uterine cervix. Br J Cancer 102 (12): 1692-8, 2010.

- Eifel PJ, Burke TW, Morris M, et al.: Adenocarcinoma as an independent risk factor for disease recurrence in patients with stage IB cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 59 (1): 38-44, 1995.

- Lee YY, Choi CH, Kim TJ, et al.: A comparison of pure adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix after radical hysterectomy in stage IB-IIA. Gynecol Oncol 120 (3): 439-43, 2011.

- Galic V, Herzog TJ, Lewin SN, et al.: Prognostic significance of adenocarcinoma histology in women with cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 125 (2): 287-91, 2012.

- Gallup DG, Harper RH, Stock RJ: Poor prognosis in patients with adenosquamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. Obstet Gynecol 65 (3): 416-22, 1985.

- Yazigi R, Sandstad J, Munoz AK, et al.: Adenosquamous carcinoma of the cervix: prognosis in stage IB. Obstet Gynecol 75 (6): 1012-5, 1990.

- Bethwaite P, Yeong ML, Holloway L, et al.: The prognosis of adenosquamous carcinomas of the uterine cervix. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 99 (9): 745-50, 1992.

- Fagundes H, Perez CA, Grigsby PW, et al.: Distant metastases after irradiation alone in carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 24 (2): 197-204, 1992.

- Monk BJ, Tian C, Rose PG, et al.: Which clinical/pathologic factors matter in the era of chemoradiation as treatment for locally advanced cervical carcinoma? Analysis of two Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) trials. Gynecol Oncol 105 (2): 427-33, 2007.

- Maiman M, Fruchter RG, Guy L, et al.: Human immunodeficiency virus infection and invasive cervical carcinoma. Cancer 71 (2): 402-6, 1993.

- Bourhis J, Le MG, Barrois M, et al.: Prognostic value of c-myc proto-oncogene overexpression in early invasive carcinoma of the cervix. J Clin Oncol 8 (11): 1789-96, 1990.

- Strang P, Eklund G, Stendahl U, et al.: S-phase rate as a predictor of early recurrences in carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Anticancer Res 7 (4B): 807-10, 1987 Jul-Aug.

- Burger RA, Monk BJ, Kurosaki T, et al.: Human papillomavirus type 18: association with poor prognosis in early stage cervical cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 88 (19): 1361-8, 1996.

- Lai CH, Chang CJ, Huang HJ, et al.: Role of human papillomavirus genotype in prognosis of early-stage cervical cancer undergoing primary surgery. J Clin Oncol 25 (24): 3628-34, 2007.

- Silva IH, Nogueira-Silva C, Figueiredo T, et al.: The impact of GGH -401C>T polymorphism on cisplatin-based chemoradiotherapy response and survival in cervical cancer. Gene 512 (2): 247-50, 2013.

- Ansink A, de Barros Lopes A, Naik R, et al.: Recurrent stage IB cervical carcinoma: evaluation of the effectiveness of routine follow up surveillance. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 103 (11): 1156-8, 1996.

- Duyn A, Van Eijkeren M, Kenter G, et al.: Recurrent cervical cancer: detection and prognosis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 81 (4): 351-5, 2002.

- Morice P, Deyrolle C, Rey A, et al.: Value of routine follow-up procedures for patients with stage I/II cervical cancer treated with combined surgery-radiation therapy. Ann Oncol 15 (2): 218-23, 2004.

Cellular Classification of Cervical Cancer

Squamous cell (epidermoid) carcinoma makes up approximately 90% of cervical cancers, and adenocarcinoma makes up approximately 10% of cervical cancers. Adenosquamous and small cell carcinomas are relatively rare. Primary sarcomas of the cervix and primary and secondary malignant lymphomas of the cervix have also been reported.

Stage Information for Cervical Cancer

Carcinoma of the cervix can spread via local invasion, the regional lymphatics, or bloodstream. Tumor dissemination is generally a function of the extent and invasiveness of the local lesion. While cancer of the cervix generally progresses in an orderly manner, occasionally a small tumor with distant metastasis is seen. For this reason, patients must be carefully evaluated for metastatic disease.

Pretreatment surgical staging is the most accurate method to determine the extent of disease,[

Tests and procedures to evaluate the extent of the disease include:

- CT scan.

- Positron emission tomography scan.

- Cystoscopy.

- Laparoscopy.

- Chest x-ray.

- Ultrasonography.[

2 ] - Magnetic resonance imaging.[

2 ]

FIGO Stage Groupings and Definitions

The Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique (FIGO) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer have designated staging to define cervical cancer; the FIGO system is most commonly used.[

| Stage | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[ |

||

| b Imaging and pathology can be used, when available, to supplement clinical findings with respect to tumor size and extent, in all stages. Pathological findings supersede imaging and clinical findings. | ||

| c The involvement of vascular/lymphatic spaces should not change the staging. The lateral extent of the lesion is no longer considered. | ||

| I | The carcinoma is strictly confined to the cervix (extension to the corpus should be disregarded). | |

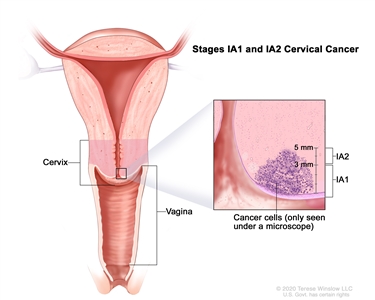

| IA | Invasive carcinoma that can be diagnosed only by microscopy, with maximum depth of invasion ≤5 mm.b |  |

| –IA1 | –Measured stromal invasion ≤3 mm in depth. | |

| –IA2 | –Measured stromal invasion >3 mm and ≤5 mm in depth. | |

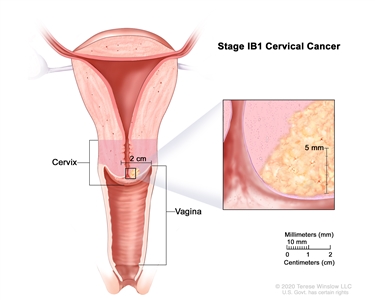

| IB | Invasive carcinoma with measured deepest invasion >5 mm (greater than stage IA); lesion limited to the cervix uteri with size measured by maximum tumor diameter.c | |

| –IB1 | –Invasive carcinoma >5 mm depth of stromal invasion and ≤2 cm in greatest dimension. |  |

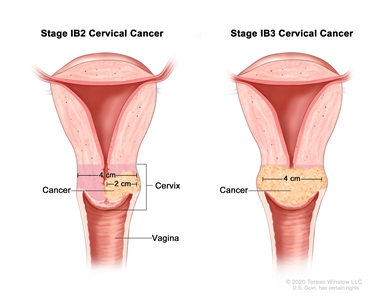

| –IB2 | –Invasive carcinoma >2 cm and ≤4 cm in greatest dimension. |  |

| –IB3 | –Invasive carcinoma >4 cm in greatest dimension. | |

| Stage | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[ |

||

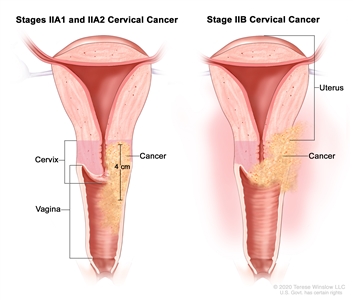

| II | The cervical carcinoma invades beyond the uterus but has not extended onto the lower third of the vagina or to the pelvic wall. |  |

| IIA | Involvement limited to the upper two-thirds of the vagina without parametrial involvement. | |

| –IIA1 | –Invasive carcinoma ≤4 cm in greatest dimension. | |

| –IIA2 | –Invasive carcinoma >4 cm in greatest dimension. | |

| IIB | With parametrial involvement but not up to the pelvic wall. | |

| Stage | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[ |

||

| b Isolated tumor cells do not change the stage, but their presence should be recorded. | ||

| c Adding notation of r (imaging) and p (pathology) to indicate the findings that are used to allocate the case to stage IIIC. For example, if imaging indicates pelvic lymph node metastasis, the stage allocation would be stage IIIC1r; if confirmed by pathological findings, it would be stage IIIC1p. The type of imaging modality or pathology technique used should always be documented. When in doubt, the lower staging should be assigned. | ||

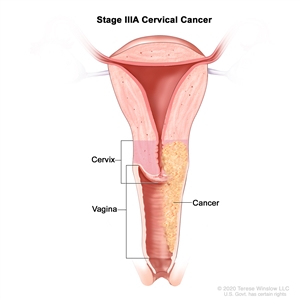

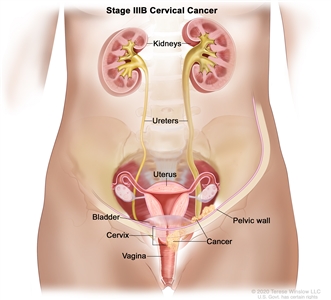

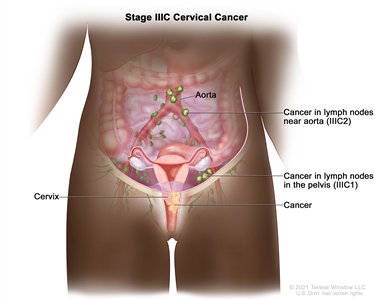

| III | The carcinoma involves the lower third of the vagina and/or extends to the pelvic wall and/or causes hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney and/or involves pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes. | |

| IIIA | Carcinoma involves the lower third of the vagina, with no extension to the pelvic wall. |  |

| IIIB | Extension to the pelvic wall and/or hydronephrosis or nonfunctioning kidney (unless known to be due to another cause). |  |

| IIIC | Involvement of pelvic and/or para-aortic lymph nodes (including micrometastases)b, irrespective of tumor size and extent (with r and p notations).c |  |

| –IIIC1 | –Pelvic lymph node metastasis only. | |

| –IIIC2 | –Para-aortic lymph node metastasis. | |

| Stage | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | ||

| a Adapted from FIGO Committee for Gynecologic Oncology.[ |

||

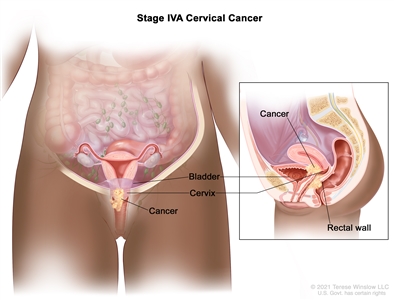

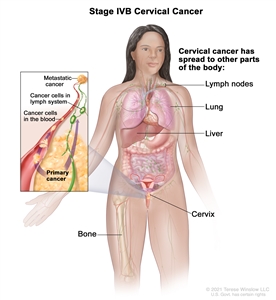

| IV | The carcinoma has extended beyond the true pelvis or has involved (biopsy proven) the mucosa of the bladder or rectum. A bullous edema, as such, does not permit a case to be allotted to stage IV. | |

| IVA | Spread of the growth to adjacent pelvic organs. |  |

| IVB | Spread to distant organs. |  |

References:

- Gold MA, Tian C, Whitney CW, et al.: Surgical versus radiographic determination of para-aortic lymph node metastases before chemoradiation for locally advanced cervical carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Cancer 112 (9): 1954-63, 2008.

- Epstein E, Testa A, Gaurilcikas A, et al.: Early-stage cervical cancer: tumor delineation by magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound - a European multicenter trial. Gynecol Oncol 128 (3): 449-53, 2013.

- Bhatla N, Aoki D, Sharma DN, et al.: Cancer of the cervix uteri: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 155 (Suppl 1): 28-44, 2021.

- Olawaiye AB, Mutch DG, Bhosale P, et al.: Cervix uteri. In: Goodman KA, Gollub M, Eng C, et al.: AJCC Cancer Staging System. Version 9. American Joint Committee on Cancer; American College of Surgeons, 2020.

Treatment Option Overview for Cervical Cancer

Patterns-of-care studies clearly demonstrate the negative prognostic effect of increasing tumor volume and spread pattern.[

| Stage ( |

Treatment Options |

|---|---|

| FIGO = Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique. | |

| In situ carcinoma of the cervix (this stage is not recognized by FIGO) | |

| |

|

| |

|

| Stage IA cervical cancer | |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| Stages IB, IIA cervical cancer | |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| Stages IIB, III, and IVA cervical cancer | |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| Stage IVB and recurrent cervical cancer | |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| Phase I and phase II clinical trials of new anticancer drugs | |

Chemoradiation Therapy

Five randomized phase III trials have shown an overall survival advantage for cisplatin-based therapy given concurrently with radiation therapy,[

- Although the positive trials vary in terms of the stage of disease, dose of radiation, and schedule of cisplatin and radiation, the trials demonstrate significant survival benefit for this combined approach. The risk of death from cervical cancer was decreased by 30% to 50% with the use of concurrent chemoradiation therapy.

- Based on these results, strong consideration should be given to the incorporation of concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy with radiation therapy in women who require radiation therapy for treatment of cervical cancer.[

2 ,3 ,4 ,5 ,6 ]

Other studies have validated these results.[

Fluorouracil dosing

The DPYD gene encodes an enzyme that catabolizes pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines, like capecitabine and fluorouracil. An estimated 1% to 2% of the population has germline pathogenic variants in DPYD, which lead to reduced DPD protein function and an accumulation of pyrimidines and fluoropyrimidines in the body.[

Surgery and Radiation Therapy

Surgery and radiation therapy are equally effective for early stage, small-volume disease.[

Therapy for patients with cancer of the cervical stump is effective and yields results that are comparable with those seen in patients with an intact uterus.[

References:

- Lanciano RM, Won M, Hanks GE: A reappraisal of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system for cervical cancer. A study of patterns of care. Cancer 69 (2): 482-7, 1992.

- Whitney CW, Sause W, Bundy BN, et al.: Randomized comparison of fluorouracil plus cisplatin versus hydroxyurea as an adjunct to radiation therapy in stage IIB-IVA carcinoma of the cervix with negative para-aortic lymph nodes: a Gynecologic Oncology Group and Southwest Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 17 (5): 1339-48, 1999.

- Morris M, Eifel PJ, Lu J, et al.: Pelvic radiation with concurrent chemotherapy compared with pelvic and para-aortic radiation for high-risk cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 340 (15): 1137-43, 1999.

- Rose PG, Bundy BN, Watkins EB, et al.: Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 340 (15): 1144-53, 1999.

- Keys HM, Bundy BN, Stehman FB, et al.: Cisplatin, radiation, and adjuvant hysterectomy compared with radiation and adjuvant hysterectomy for bulky stage IB cervical carcinoma. N Engl J Med 340 (15): 1154-61, 1999.

- Peters WA, Liu PY, Barrett RJ, et al.: Concurrent chemotherapy and pelvic radiation therapy compared with pelvic radiation therapy alone as adjuvant therapy after radical surgery in high-risk early-stage cancer of the cervix. J Clin Oncol 18 (8): 1606-13, 2000.

- Pearcey R, Brundage M, Drouin P, et al.: Phase III trial comparing radical radiotherapy with and without cisplatin chemotherapy in patients with advanced squamous cell cancer of the cervix. J Clin Oncol 20 (4): 966-72, 2002.

- Thomas GM: Improved treatment for cervical cancer--concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy. N Engl J Med 340 (15): 1198-200, 1999.

- Rose PG, Bundy BN: Chemoradiation for locally advanced cervical cancer: does it help? J Clin Oncol 20 (4): 891-3, 2002.

- Chemoradiotherapy for Cervical Cancer Meta-Analysis Collaboration: Reducing uncertainties about the effects of chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 18 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol 26 (35): 5802-12, 2008.

- Sharma BB, Rai K, Blunt H, et al.: Pathogenic DPYD Variants and Treatment-Related Mortality in Patients Receiving Fluoropyrimidine Chemotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oncologist 26 (12): 1008-1016, 2021.

- Lam SW, Guchelaar HJ, Boven E: The role of pharmacogenetics in capecitabine efficacy and toxicity. Cancer Treat Rev 50: 9-22, 2016.

- Shakeel F, Fang F, Kwon JW, et al.: Patients carrying DPYD variant alleles have increased risk of severe toxicity and related treatment modifications during fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy. Pharmacogenomics 22 (3): 145-155, 2021.

- Amstutz U, Henricks LM, Offer SM, et al.: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) Guideline for Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase Genotype and Fluoropyrimidine Dosing: 2017 Update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 103 (2): 210-216, 2018.

- Henricks LM, Lunenburg CATC, de Man FM, et al.: DPYD genotype-guided dose individualisation of fluoropyrimidine therapy in patients with cancer: a prospective safety analysis. Lancet Oncol 19 (11): 1459-1467, 2018.

- Lau-Min KS, Varughese LA, Nelson MN, et al.: Preemptive pharmacogenetic testing to guide chemotherapy dosing in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies: a qualitative study of barriers to implementation. BMC Cancer 22 (1): 47, 2022.

- Brooks GA, Tapp S, Daly AT, et al.: Cost-effectiveness of DPYD Genotyping Prior to Fluoropyrimidine-based Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Colon Cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 21 (3): e189-e195, 2022.

- Baker SD, Bates SE, Brooks GA, et al.: DPYD Testing: Time to Put Patient Safety First. J Clin Oncol 41 (15): 2701-2705, 2023.

- Eifel PJ, Burke TW, Delclos L, et al.: Early stage I adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix: treatment results in patients with tumors less than or equal to 4 cm in diameter. Gynecol Oncol 41 (3): 199-205, 1991.

- Kovalic JJ, Grigsby PW, Perez CA, et al.: Cervical stump carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 20 (5): 933-8, 1991.

Treatment of In Situ Cervical Cancer

Consensus guidelines have been issued for managing women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ.[

The choice of treatment depends on the extent of disease and several patient factors, including age, cell type, desire to preserve fertility, and medical condition.

Treatment Options forIn Situ Cervical Cancer

Treatment options for in situ cervical cancer include:

-

Conization .- Cold-knife conization (scalpel).

- Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP).[

3 ,4 ] - Laser therapy.[

5 ]

-

Hysterectomy for postreproductive patients . -

Internal radiation therapy for medically inoperable patients.

Hysterectomy is the standard treatment for patients with adenocarcinoma in situ. The disease, which originates in the endocervical canal, may be more difficult to completely excise with a conization procedure. Conization may be offered to select patients with adenocarcinoma in situ who desire future fertility.

Conization

When the endocervical canal is involved, laser or cold-knife conization may be used for selected patients to preserve the uterus, avoid radiation therapy, and more extensive surgery.[

In selected cases, the outpatient LEEP may be an acceptable alternative to cold-knife conization. This procedure requires only local anesthesia and obviates the risks associated with general anesthesia for cold-knife conization.[

Evidence (conization using LEEP):

- A trial comparing LEEP with cold-knife cone biopsy showed no difference in the likelihood of complete excision of dysplasia.[

6 ] - Two case reports suggested that the use of LEEP in patients with occult invasive cancer led to an inability to accurately determine depth of invasion when a focus of the cancer was transected.[

11 ]

Hysterectomy for postreproductive patients

Hysterectomy is standard therapy for women with cervical adenocarcinoma in situ because of the location of the disease in the endocervical canal and the possibility of skip lesions in this region, making margin status a less reliable prognostic factor. However, the effect of hysterectomy compared with conservative surgical measures on mortality has not been studied. Hysterectomy may be performed for squamous cell carcinoma in situ if conization is not possible because of previous surgery, or if positive margins are noted after conization therapy. Hysterectomy is not an acceptable front-line therapy for squamous carcinoma in situ.[

Internal radiation therapy for medically inoperable patients

For medically inoperable patients, a single intracavitary insertion with tandem and ovoids for 5,000 mg hours (80 Gy vaginal surface dose) may be used.[

Current Clinical Trials

Use our

References:

- Wright TC, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, et al.: 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or adenocarcinoma in situ. Am J Obstet Gynecol 197 (4): 340-5, 2007.

- Shumsky AG, Stuart GC, Nation J: Carcinoma of the cervix following conservative management of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol 53 (1): 50-4, 1994.

- Wright VC, Chapman W: Intraepithelial neoplasia of the lower female genital tract: etiology, investigation, and management. Semin Surg Oncol 8 (4): 180-90, 1992 Jul-Aug.

- Bloss JD: The use of electrosurgical techniques in the management of premalignant diseases of the vulva, vagina, and cervix: an excisional rather than an ablative approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol 169 (5): 1081-5, 1993.

- Tsukamoto N: Treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia with the carbon dioxide laser. Gynecol Oncol 21 (3): 331-6, 1985.

- Girardi F, Heydarfadai M, Koroschetz F, et al.: Cold-knife conization versus loop excision: histopathologic and clinical results of a randomized trial. Gynecol Oncol 55 (3 Pt 1): 368-70, 1994.

- Wright TC, Gagnon S, Richart RM, et al.: Treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia using the loop electrosurgical excision procedure. Obstet Gynecol 79 (2): 173-8, 1992.

- Naumann RW, Bell MC, Alvarez RD, et al.: LLETZ is an acceptable alternative to diagnostic cold-knife conization. Gynecol Oncol 55 (2): 224-8, 1994.

- Duesing N, Schwarz J, Choschzick M, et al.: Assessment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) with colposcopic biopsy and efficacy of loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP). Arch Gynecol Obstet 286 (6): 1549-54, 2012.

- Widrich T, Kennedy AW, Myers TM, et al.: Adenocarcinoma in situ of the uterine cervix: management and outcome. Gynecol Oncol 61 (3): 304-8, 1996.

- Eddy GL, Spiegel GW, Creasman WT: Adverse effect of electrosurgical loop excision on assignment of FIGO stage in cervical cancer: report of two cases. Gynecol Oncol 55 (2): 313-7, 1994.

- Massad LS: New guidelines on cervical cancer screening: more than just the end of annual Pap testing. J Low Genit Tract Dis 16 (3): 172-4, 2012.

- Grigsby PW, Perez CA: Radiotherapy alone for medically inoperable carcinoma of the cervix: stage IA and carcinoma in situ. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 21 (2): 375-8, 1991.

Treatment of Stage IA Cervical Cancer

Treatment Options for Stage IA1 Cervical Cancer

Treatment options for

-

Conization . -

Total hysterectomy .

Conization

If the depth of invasion is less than 3 mm, no vascular or lymphatic channel invasion is noted, and the margins of the cone are negative, conization alone may be appropriate in patients who wish to preserve fertility.[

Total hysterectomy

If the depth of invasion is less than 3 mm, which is proven by cone biopsy with clear margins,[

Treatment Options for Stage IA2 Cervical Cancer

Treatment options for

-

Modified radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy. -

Radical trachelectomy. -

Intracavitary radiation therapy.

Modified radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy

For patients with tumor invasion between 3 mm and 5 mm, modified radical hysterectomy with pelvic-node dissection has been recommended because of a reported risk of lymph-node metastasis of as much as 10%.[

Evidence (open abdominal surgery [open] versus minimally invasive surgery [MIS]):

- A multicenter, international, randomized trial, the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC [NCT00614211]) trial explored the efficacy of radical hysterectomy and staging via open abdominal surgery versus MIS for patients with early-stage cervical cancer.[

3 ] Patients with stages IA1 (with lymphovascular space invasion), IA2, and IB1 disease and histological subtypes of squamous cell, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous carcinoma were eligible for inclusion. The primary end point was noninferiority of MIS compared with open surgery. The metric used was the percent of disease-free patients at 4.5 years postsurgery. The secondary end points were a comparison of the recurrence and survival rates between the two groups.Of the planned 740 patients, 632 were accrued when the study was stopped early because of an imbalance in deaths between the two groups. Of 631 eligible patients, 319 were assigned to MIS and 312 to open surgery.

- The disease-free survival (DFS) rate at 4.5 years was 86% for the MIS group and 96.5% for the open-surgery group (95% confidence interval [CI], -16.4 to -4.7). At 3 years, the MIS group had a DFS rate of 91.2% versus 97.1% for the open-surgery group (hazard ratio [HR] for disease recurrence or death, 3.74; 95% CI, 1.63–8.58).

- The MIS group also had a lower 3-year overall survival (OS) rate (93.8% vs. 99.0% for the open-surgery group; HR for death from any cause, 6.0; 95% CI, 1.77–20.30).[

3 ][Level of evidence A1]

The study concluded that MIS was inferior to an open abdominal approach and should not replace open surgery as the standard for patients with cervical cancer.

- An epidemiological study used two large U.S. databases, the National Cancer Database (NCDB) and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Database, and confirmed a reduction in OS in patients undergoing MIS radical hysterectomy for stage IA2 and stage IB1 cervical cancer from 2010 to 2013. Additionally, among women who underwent radical hysterectomy in the years 2000 to 2010, there was a decrease in OS after 2006, coincident with the widespread adoption of MIS for cervical cancer.[

4 ][Level of evidence C1]

Although questions remain regarding the use of MIS radical hysterectomy for some subpopulations of good-risk patients, the data from this trial suggest that open abdominal surgery should be considered the standard of care for patients with early-stage cervical cancer who are candidates for radical hysterectomy.

Radical trachelectomy

Patients with stages IA2 to IB disease who desire future fertility may be candidates for radical trachelectomy. In this procedure, the cervix and lateral parametrial tissues are removed, and the uterine body and ovaries are maintained. Most centers use the following criteria for patient selection:

- Desire for future pregnancy.

- Age younger than 40 years.

- Presumed stage IA2 to IB1 disease and a lesion size no greater than 2 cm.

- Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging that shows a margin from the most distal edge of the tumor to the lower uterine segment.

- Squamous, adenosquamous, or adenocarcinoma cell types.

Intraoperatively, the patient is assessed in a manner similar to a radical hysterectomy; the procedure is aborted if more advanced disease than expected is encountered. The margins of the specimen are also assessed at the time of surgery, and a radical hysterectomy is performed if inadequate margins are obtained.[

Intracavitary radiation therapy

Intracavitary radiation therapy is an option when palliative treatment is being considered for women who are not surgical candidates or who have other medical contraindications.

If the depth of invasion is less than 3 mm, no capillary lymphatic space invasion is noted, and the frequency of lymph-node involvement is sufficiently low, external-beam radiation therapy is not required. One or two insertions with tandem and ovoids for 6,500 mg to 8,000 mg hours (100–125 Gy vaginal surface dose) are recommended.[

Current Clinical Trials

Use our

References:

- Sevin BU, Nadji M, Averette HE, et al.: Microinvasive carcinoma of the cervix. Cancer 70 (8): 2121-8, 1992.

- Jones WB, Mercer GO, Lewis JL, et al.: Early invasive carcinoma of the cervix. Gynecol Oncol 51 (1): 26-32, 1993.

- Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al.: Minimally Invasive versus Abdominal Radical Hysterectomy for Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med 379 (20): 1895-1904, 2018.

- Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al.: Survival after Minimally Invasive Radical Hysterectomy for Early-Stage Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med 379 (20): 1905-1914, 2018.

- Covens A, Shaw P, Murphy J, et al.: Is radical trachelectomy a safe alternative to radical hysterectomy for patients with stage IA-B carcinoma of the cervix? Cancer 86 (11): 2273-9, 1999.

- Dargent D, Martin X, Sacchetoni A, et al.: Laparoscopic vaginal radical trachelectomy: a treatment to preserve the fertility of cervical carcinoma patients. Cancer 88 (8): 1877-82, 2000.

- Plante M, Renaud MC, Hoskins IA, et al.: Vaginal radical trachelectomy: a valuable fertility-preserving option in the management of early-stage cervical cancer. A series of 50 pregnancies and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 98 (1): 3-10, 2005.

- Shepherd JH, Spencer C, Herod J, et al.: Radical vaginal trachelectomy as a fertility-sparing procedure in women with early-stage cervical cancer-cumulative pregnancy rate in a series of 123 women. BJOG 113 (6): 719-24, 2006.

- Wethington SL, Cibula D, Duska LR, et al.: An international series on abdominal radical trachelectomy: 101 patients and 28 pregnancies. Int J Gynecol Cancer 22 (7): 1251-7, 2012.

- Grigsby PW, Perez CA: Radiotherapy alone for medically inoperable carcinoma of the cervix: stage IA and carcinoma in situ. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 21 (2): 375-8, 1991.

Treatment of Stages IB and IIA Cervical Cancer

Treatment Options for Stages IB and IIA Cervical Cancer

Treatment options for

-

Radiation therapy with concomitant chemotherapy . -

Radical hysterectomy and bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy with or without total pelvic radiation therapy plus chemotherapy . -

Radical trachelectomy . -

Radiation therapy alone . -

Immunotherapy . -

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (under clinical evaluation). -

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) (under clinical evaluation).

Tumor size is an important prognostic factor to carefully evaluate when choosing optimal therapy.[

Either radiation therapy or radical hysterectomy and bilateral lymph–node dissection results in cure rates of 85% to 90% for women with Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique (FIGO) stages IA2 and IB1 small-volume disease. The choice of either treatment depends on patient factors and available local expertise. A randomized trial reported identical 5-year overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) rates when comparing radiation therapy with radical hysterectomy.[

In patients with stage IB2 disease, for tumors that expand the cervix more than 4 cm, the primary treatment should be concomitant chemotherapy and radiation therapy.[

Radiation therapy with concomitant chemotherapy

Concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy with radiation therapy is the standard of care for women who require radiation therapy for treatment of cervical cancer.[

Evidence (radiation with concomitant chemotherapy):

- Three randomized phase III trials have shown an OS advantage for cisplatin-based therapy given concurrently with radiation therapy,[

4 ,5 ,6 ,7 ] while one trial that examined this regimen demonstrated no benefit.[8 ] The patient populations in these studies included women with FIGO stages IB2 to IVA cervical cancer treated with primary radiation therapy, and women with FIGO stages I to IIA disease who, at the time of primary surgery, were found to have poor prognostic factors, including metastatic disease in pelvic lymph nodes, parametrial disease, and positive surgical margins.- Although the positive trials vary somewhat in terms of the stage of disease, dose of radiation, and schedule of cisplatin and radiation, the trials demonstrate significant survival benefit for this combined approach.

- The risk of death from cervical cancer was decreased by 30% to 50% with the use of concurrent chemoradiation therapy.

- Other trials have confirmed these findings.[

9 ,10 ]

Brachytherapy

Standard radiation therapy for cervical cancer includes brachytherapy after external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT). Although low-dose rate (LDR) brachytherapy, typically with cesium Cs 137 (137Cs), has been the traditional approach, the use of high-dose rate (HDR) therapy, typically with iridium Ir 192, is rapidly increasing. HDR brachytherapy has the advantages of eliminating radiation exposure to medical personnel, a shorter treatment time, patient convenience, and improved outpatient management. The American Brachytherapy Society has published guidelines for the use of LDR and HDR brachytherapy as components of cervical cancer treatment.[

Evidence (brachytherapy):

- In three randomized trials, HDR brachytherapy was comparable with LDR brachytherapy in terms of local-regional control and complication rates.[

13 ,14 ,15 ][Level of evidence B1]Surgery after radiation therapy may be indicated for some patients with tumors confined to the cervix that respond incompletely to radiation therapy or for patients whose vaginal anatomy precludes optimal brachytherapy.[

16 ]

Pelvic node disease

The resection of macroscopically involved pelvic nodes may improve rates of local control with postoperative radiation therapy.[

Radical hysterectomy and bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy with or without total pelvic radiation therapy plus chemotherapy

Women with stages IB to IIA disease may consider radical hysterectomy and bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy.

Evidence (radical hysterectomy and bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy with or without total pelvic radiation therapy plus chemotherapy):

- An Italian group randomly assigned 343 women with stage IB and IIA cervical cancer to surgery or radiation therapy. The radiation therapy included EBRT and one 137Cs LDR insertion, with a total dose to point A from 70 to 90 Gy (median 76 Gy). Patients in the surgery arm underwent a class III radical hysterectomy, pelvic lymphadenectomy, and selective, para-aortic lymph–node dissection. Adjuvant radiation therapy was given to patients with high-risk pathological features in the uterine specimen or positive lymph nodes. Adjuvant radiation therapy was EBRT to a total dose of 50.4 Gy over 5 to 6 weeks.[

2 ][Level of evidence A1]- The primary outcome was 5-year OS, with secondary measures of rate of recurrence and complications. With a median follow-up of 87 months, the OS rate was the same in both groups at 83% (hazard ratio [HR], 1.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.7–2.3; P = .8).

- Complications were highest among the patients who received adjuvant radiation after surgery.

- In general, radical hysterectomy should be avoided in patients who are likely to require adjuvant therapy.

Evidence (open abdominal surgery [open] versus minimally invasive surgery [MIS]):

- A multicenter, international, randomized trial, the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC [NCT00614211]) trial, explored the efficacy of radical hysterectomy and staging via open abdominal surgery (open) versus MIS for patients with early-stage cervical cancer.[

22 ] Patients with stages IA1 (with lymphovascular space invasion), IA2, and IB1 disease and histological subtypes of squamous cell, adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma were eligible for inclusion. The primary end point was noninferiority of MIS compared with open surgery; the metric used was the percent of disease-free patients at 4.5 years postsurgery. The secondary end points were a comparison of the recurrence and survival rates between the two groups.Of the planned 740 patients, 632 were accrued when the study was stopped early because of an imbalance in deaths between the two groups. Of 631 eligible patients, 319 were assigned to MIS and 312 to open surgery.

- The DFS rate at 4.5 years was 86% for the MIS group and 96.5% for the open-surgery group (95% CI, -16.4 to -4.7). At 3 years, the MIS group had a DFS rate of 91.2% versus 97.1% for the open-surgery group (HR for disease recurrence or death, 3.74; 95% CI, 1.63–8.58).

- The MIS group also had a lower 3-year OS rate (93.8% vs. 99.0% for the open-surgery group; HR for death from any cause, 6.0; 95% CI, 1.77–20.30).[

22 ][Level of evidence A1]

The study concluded that MIS was inferior to an open abdominal approach and should not replace open surgery as the standard for cervical cancer patients.

- An epidemiological study using two large U.S. databases (National Cancer Database [NCDB] and Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results [SEER] Program database) confirmed a reduction in OS in patients undergoing MIS radical hysterectomy for stage IA2 and stage IB1 cervical cancer from 2010 to 2013. Additionally, among women who underwent radical hysterectomy in the years 2000 to 2010, there was a decrease in OS after 2006, coincident with the widespread adoption of MIS for cervical cancer.[

23 ][Level of evidence C1]

Although questions remain regarding the use of MIS radical hysterectomy for some subpopulations of good-risk patients, the data from this trial suggest that open abdominal surgery should be considered the standard of care for patients with early-stage cervical cancer who are candidates for radical hysterectomy.

Adjuvant radiation therapy postsurgery

Based on recurrence rates in clinical trials, two classes of recurrence risk have been defined. Patients with a combination of large tumor size, lymph vascular space invasion, and deep stromal invasion in the hysterectomy specimen are deemed to have intermediate-risk disease. These patients are candidates for adjuvant EBRT.[

Evidence (adjuvant radiation therapy postsurgery):

- The Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) compared adjuvant radiation therapy alone with radiation therapy plus cisplatin plus fluorouracil (5-FU) after radical hysterectomy for patients in the high-risk group. Postoperative patients were eligible if their pathology showed any one of the following: positive parametria, positive margins, or positive lymph nodes. Patients in both arms received 49 Gy to the pelvis. Patients in the experimental arm also received cisplatin (70 mg/m2) and a 96-hour infusion of 5-FU (1,000 mg/m2 /d every 3 weeks for four cycles); the first two cycles were concurrent with the radiation therapy.[

6 ][Level of evidence A1]- There were 268 patients evaluated with a primary end point of OS. The study results were reported early because of the positive results in other trials of concomitant cisplatin and radiation therapy.

- The estimated 4-year survival rate was 81% for chemotherapy plus radiation therapy and 71% for radiation therapy alone (HR, 1.96; P = .007).

- As expected, grade 4 toxicity was more common in the chemotherapy plus radiation therapy group, with hematologic toxicity predominating.

Radical surgery has been performed for small lesions, but the high incidence of pathological factors leading to postoperative radiation with or without chemotherapy make primary concomitant chemotherapy and radiation a more common approach in patients with larger tumors. Radiation in the range of 50 Gy administered for 5 weeks plus chemotherapy with cisplatin with or without 5-FU should be considered in patients with a high risk of recurrence.

Para-aortic nodal disease

After surgical staging, patients found to have small-volume para-aortic nodal disease and controllable pelvic disease may be cured with pelvic and para-aortic radiation therapy.[

Radical trachelectomy

Patients with presumed early-stage disease who desire future fertility may be candidates for radical trachelectomy. In this procedure, the cervix and lateral parametrial tissues are removed, and the uterine body and ovaries are maintained. The patient selection differs somewhat between groups; however, general criteria include:

- Desire for future pregnancy.

- Age younger than 40 years.

- Presumed stage IA2 to IB1 disease and a lesion size no greater than 2 cm.

- Preoperative magnetic resonance imaging that shows a margin from the most distal edge of the tumor to the lower uterine segment.

- Squamous, adenosquamous, or adenocarcinoma cell types.

Intraoperatively, the patient is assessed in a manner similar to a radical hysterectomy; the procedure is aborted if more advanced disease than expected is encountered. The margins of the specimen are also assessed at the time of surgery, and a radical hysterectomy is performed if inadequate margins are obtained.[

Radiation therapy alone

External-beam pelvic radiation therapy combined with two or more intracavitary brachytherapy applications is appropriate therapy for patients with stage IA2 and IB1 lesions. For patients with stage IB2 and larger lesions, radiosensitizing chemotherapy is indicated. The role of radiosensitizing chemotherapy in patients with stage IA2 and IB1 lesions is untested. However, it may prove beneficial in certain cases.

Immunotherapy

Evidence (immunotherapy):

- KEYNOTE-A18 (NCT04221945) was a multicenter, phase III, randomized trial that included 1,060 women with newly diagnosed squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous carcinoma of the cervix. Patients had stage IB2 or IIB node-positive disease or stage III to IVA disease and had received no prior treatment. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either chemoradiation therapy (with cisplatin) plus pembrolizumab (every 3 weeks for five cycles) or chemoradiation therapy plus placebo. All patients received maintenance therapy with pembrolizumab or placebo every 6 weeks for 15 cycles. All patients received brachytherapy, and 94% of patients had programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)–positive disease. The dual primary end points were progression-free survival (PFS) and OS. The median follow-up time was 17.9 months.[

33 ]- The 24-month OS rate was 87% in the pembrolizumab group and 81% in the placebo group (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.49–1.07).[

33 ][Level of evidence B1] - There was a statistically significant improvement in PFS (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.55–0.89). The 24-month PFS rate was 68% in the pembrolizumab group and 57% in the placebo group.

- Patients with stage III or IV disease had a greater improvement in PFS (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.42–0.80).

- The 24-month OS rate was 87% in the pembrolizumab group and 81% in the placebo group (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.49–1.07).[

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Several groups have investigated the role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to convert patients who are conventional candidates for chemoradiation into candidates for radical surgery.[

EORTC-55994 (NCT00039338) randomly assigned patients with stages IB2, IIA2, and IIB cervical cancer to standard chemoradiation or neoadjuvant chemotherapy (with a cisplatin backbone for three cycles) followed by evaluation for surgery. With OS as the primary end point, this trial may delineate whether there is a role for neoadjuvant chemotherapy for this patient population.

IMRT

IMRT is a radiation therapy technique that allows for conformal dosing of target anatomy while sparing neighboring tissue. Theoretically, this technique should decrease radiation therapy–related toxicity, but this could come at the cost of decreased efficacy if tissue is inappropriately excluded from the treatment field. Several institutions have reported their experience with IMRT for postoperative adjuvant therapy in patients with intermediate-risk and high-risk disease after radical surgery.[

Current Clinical Trials

Use our

References:

- Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Nene SM, et al.: Effect of tumor size on the prognosis of carcinoma of the uterine cervix treated with irradiation alone. Cancer 69 (11): 2796-806, 1992.

- Landoni F, Maneo A, Colombo A, et al.: Randomised study of radical surgery versus radiotherapy for stage Ib-IIa cervical cancer. Lancet 350 (9077): 535-40, 1997.

- Eifel PJ, Burke TW, Delclos L, et al.: Early stage I adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix: treatment results in patients with tumors less than or equal to 4 cm in diameter. Gynecol Oncol 41 (3): 199-205, 1991.

- Morris M, Eifel PJ, Lu J, et al.: Pelvic radiation with concurrent chemotherapy compared with pelvic and para-aortic radiation for high-risk cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 340 (15): 1137-43, 1999.

- Keys HM, Bundy BN, Stehman FB, et al.: Cisplatin, radiation, and adjuvant hysterectomy compared with radiation and adjuvant hysterectomy for bulky stage IB cervical carcinoma. N Engl J Med 340 (15): 1154-61, 1999.

- Peters WA, Liu PY, Barrett RJ, et al.: Concurrent chemotherapy and pelvic radiation therapy compared with pelvic radiation therapy alone as adjuvant therapy after radical surgery in high-risk early-stage cancer of the cervix. J Clin Oncol 18 (8): 1606-13, 2000.

- Thomas GM: Improved treatment for cervical cancer--concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy. N Engl J Med 340 (15): 1198-200, 1999.

- Pearcey R, Brundage M, Drouin P, et al.: Phase III trial comparing radical radiotherapy with and without cisplatin chemotherapy in patients with advanced squamous cell cancer of the cervix. J Clin Oncol 20 (4): 966-72, 2002.

- Rose PG, Bundy BN: Chemoradiation for locally advanced cervical cancer: does it help? J Clin Oncol 20 (4): 891-3, 2002.

- Chemoradiotherapy for Cervical Cancer Meta-Analysis Collaboration: Reducing uncertainties about the effects of chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 18 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol 26 (35): 5802-12, 2008.

- Nag S, Chao C, Erickson B, et al.: The American Brachytherapy Society recommendations for low-dose-rate brachytherapy for carcinoma of the cervix. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 52 (1): 33-48, 2002.

- Nag S, Erickson B, Thomadsen B, et al.: The American Brachytherapy Society recommendations for high-dose-rate brachytherapy for carcinoma of the cervix. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 48 (1): 201-11, 2000.

- Patel FD, Sharma SC, Negi PS, et al.: Low dose rate vs. high dose rate brachytherapy in the treatment of carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 28 (2): 335-41, 1994.

- Hareyama M, Sakata K, Oouchi A, et al.: High-dose-rate versus low-dose-rate intracavitary therapy for carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a randomized trial. Cancer 94 (1): 117-24, 2002.

- Lertsanguansinchai P, Lertbutsayanukul C, Shotelersuk K, et al.: Phase III randomized trial comparing LDR and HDR brachytherapy in treatment of cervical carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 59 (5): 1424-31, 2004.

- Thoms WW, Eifel PJ, Smith TL, et al.: Bulky endocervical carcinoma: a 23-year experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 23 (3): 491-9, 1992.

- Downey GO, Potish RA, Adcock LL, et al.: Pretreatment surgical staging in cervical carcinoma: therapeutic efficacy of pelvic lymph node resection. Am J Obstet Gynecol 160 (5 Pt 1): 1055-61, 1989.

- Vigliotti AP, Wen BC, Hussey DH, et al.: Extended field irradiation for carcinoma of the uterine cervix with positive periaortic nodes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 23 (3): 501-9, 1992.

- Weiser EB, Bundy BN, Hoskins WJ, et al.: Extraperitoneal versus transperitoneal selective paraaortic lymphadenectomy in the pretreatment surgical staging of advanced cervical carcinoma (a Gynecologic Oncology Group study). Gynecol Oncol 33 (3): 283-9, 1989.

- Fine BA, Hempling RE, Piver MS, et al.: Severe radiation morbidity in carcinoma of the cervix: impact of pretherapy surgical staging and previous surgery. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 31 (4): 717-23, 1995.

- Estape RE, Angioli R, Madrigal M, et al.: Close vaginal margins as a prognostic factor after radical hysterectomy. Gynecol Oncol 68 (3): 229-32, 1998.

- Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al.: Minimally Invasive versus Abdominal Radical Hysterectomy for Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med 379 (20): 1895-1904, 2018.

- Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al.: Survival after Minimally Invasive Radical Hysterectomy for Early-Stage Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med 379 (20): 1905-1914, 2018.

- Sedlis A, Bundy BN, Rotman MZ, et al.: A randomized trial of pelvic radiation therapy versus no further therapy in selected patients with stage IB carcinoma of the cervix after radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy: A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol 73 (2): 177-83, 1999.

- Cunningham MJ, Dunton CJ, Corn B, et al.: Extended-field radiation therapy in early-stage cervical carcinoma: survival and complications. Gynecol Oncol 43 (1): 51-4, 1991.

- Rotman M, Pajak TF, Choi K, et al.: Prophylactic extended-field irradiation of para-aortic lymph nodes in stages IIB and bulky IB and IIA cervical carcinomas. Ten-year treatment results of RTOG 79-20. JAMA 274 (5): 387-93, 1995.

- Poorvu PD, Sadow CA, Townamchai K, et al.: Duodenal and other gastrointestinal toxicity in cervical and endometrial cancer treated with extended-field intensity modulated radiation therapy to paraaortic lymph nodes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 85 (5): 1262-8, 2013.

- Covens A, Shaw P, Murphy J, et al.: Is radical trachelectomy a safe alternative to radical hysterectomy for patients with stage IA-B carcinoma of the cervix? Cancer 86 (11): 2273-9, 1999.

- Dargent D, Martin X, Sacchetoni A, et al.: Laparoscopic vaginal radical trachelectomy: a treatment to preserve the fertility of cervical carcinoma patients. Cancer 88 (8): 1877-82, 2000.

- Plante M, Renaud MC, Hoskins IA, et al.: Vaginal radical trachelectomy: a valuable fertility-preserving option in the management of early-stage cervical cancer. A series of 50 pregnancies and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol 98 (1): 3-10, 2005.

- Shepherd JH, Spencer C, Herod J, et al.: Radical vaginal trachelectomy as a fertility-sparing procedure in women with early-stage cervical cancer-cumulative pregnancy rate in a series of 123 women. BJOG 113 (6): 719-24, 2006.

- Wethington SL, Cibula D, Duska LR, et al.: An international series on abdominal radical trachelectomy: 101 patients and 28 pregnancies. Int J Gynecol Cancer 22 (7): 1251-7, 2012.

- Lorusso D, Xiang Y, Hasegawa K, et al.: Pembrolizumab or placebo with chemoradiotherapy followed by pembrolizumab or placebo for newly diagnosed, high-risk, locally advanced cervical cancer (ENGOT-cx11/GOG-3047/KEYNOTE-A18): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 clinical trial. Lancet 403 (10434): 1341-1350, 2024.

- Ferrandina G, Margariti PA, Smaniotto D, et al.: Long-term analysis of clinical outcome and complications in locally advanced cervical cancer patients administered concomitant chemoradiation followed by radical surgery. Gynecol Oncol 119 (3): 404-10, 2010.

- Ferrandina G, Distefano MG, De Vincenzo R, et al.: Paclitaxel, epirubicin, and cisplatin (TEP) regimen as neoadjuvant treatment in locally advanced cervical cancer: long-term results. Gynecol Oncol 128 (3): 518-23, 2013.

- Zanaboni F, Grijuela B, Giudici S, et al.: Weekly topotecan and cisplatin (TOPOCIS) as neo-adjuvant chemotherapy for locally-advanced squamous cervical carcinoma: Results of a phase II multicentric study. Eur J Cancer 49 (5): 1065-72, 2013.

- Manci N, Marchetti C, Di Tucci C, et al.: A prospective phase II study of topotecan (Hycamtin®) and cisplatin as neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 122 (2): 285-90, 2011.

- Gong L, Lou JY, Wang P, et al.: Clinical evaluation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by radical surgery in the management of stage IB2-IIB cervical cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 117 (1): 23-6, 2012.

- Benedetti-Panici P, Greggi S, Colombo A, et al.: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radical surgery versus exclusive radiotherapy in locally advanced squamous cell cervical cancer: results from the Italian multicenter randomized study. J Clin Oncol 20 (1): 179-88, 2002.

- Chen MF, Tseng CJ, Tseng CC, et al.: Adjuvant concurrent chemoradiotherapy with intensity-modulated pelvic radiotherapy after surgery for high-risk, early stage cervical cancer patients. Cancer J 14 (3): 200-6, 2008 May-Jun.

- Hasselle MD, Rose BS, Kochanski JD, et al.: Clinical outcomes of intensity-modulated pelvic radiation therapy for carcinoma of the cervix. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 80 (5): 1436-45, 2011.

- Folkert MR, Shih KK, Abu-Rustum NR, et al.: Postoperative pelvic intensity-modulated radiotherapy and concurrent chemotherapy in intermediate- and high-risk cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 128 (2): 288-93, 2013.

Treatment of Stages IIB, III, and IVA Cervical Cancer

Treatment Options for Stages IIB, III, and IVA Cervical Cancer

Primary tumor size is an important prognostic factor to carefully evaluate when choosing optimal therapy.[

Treatment options for

-

Radiation therapy with concomitant chemotherapy. [4 ] -

Interstitial brachytherapy . -

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy . -

Immunotherapy .

Radiation therapy with concomitant chemotherapy

Strong consideration should be given to the use of intracavitary radiation therapy and external-beam radiation therapy (EBRT) to the pelvis combined with cisplatin or cisplatin/fluorouracil (5-FU).[

Evidence (radiation therapy with concomitant chemotherapy):

- Five randomized phase III trials have shown an overall survival (OS) advantage for cisplatin-based therapy given concurrently with radiation therapy,[

5 ,6 ,7 ,8 ,9 ,10 ] but one trial that examined this regimen demonstrated no benefit.[13 ] The patient populations in these studies included women with Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d'Obstétrique (FIGO) stages IB2 to IVA cervical cancer treated with primary radiation therapy, and women with FIGO stages I to IIA disease who, at the time of primary surgery, were found to have poor prognostic factors, including metastatic disease in pelvic lymph nodes, parametrial disease, and positive surgical margins.- Although the positive trials vary somewhat in terms of the stage of disease, dose of radiation, and schedule of cisplatin and radiation, the trials demonstrate significant survival benefit for this combined approach.

- The risk of death from cervical cancer was decreased by 30% to 50% with the use of concurrent chemoradiation therapy.

Evidence (low-dose rate vs. high-dose rate intracavitary radiation therapy):

- Although low-dose rate (LDR) brachytherapy, typically with cesium Cs 137, has been the traditional approach, the use of high-dose rate (HDR) therapy, typically with iridium Ir 192, is rapidly increasing. HDR brachytherapy provides the advantage of eliminating radiation exposure to medical personnel, a shorter treatment time, patient convenience, and improved outpatient management. The American Brachytherapy Society has published guidelines for the use of LDR and HDR brachytherapy as a component of cervical cancer treatment.[

14 ,15 ] - In three randomized trials, HDR brachytherapy was comparable with LDR brachytherapy in terms of local-regional control and complication rates.[

16 ,17 ,18 ][Level of evidence B1] - In an attempt to improve upon standard chemoradiation, a phase III randomized trial compared concurrent gemcitabine plus cisplatin and radiation therapy followed by adjuvant gemcitabine and cisplatin (experimental arm) with concurrent cisplatin plus radiation (standard chemoradiation) in patients with stages IIB to IVA cervical cancer.[

19 ][Level of evidence A1] A total of 515 patients from nine countries were enrolled. The schedule for the experimental arm was cisplatin (40 mg/m2) and gemcitabine (125 mg/m2) weekly for 6 weeks, with concurrent EBRT (50.4 Gy in 28 fractions) followed by brachytherapy (30–35 Gy in 96 hours) and then two adjuvant 21-day cycles of cisplatin (50 mg/m2) on day 1 plus gemcitabine (1,000 mg/m2) on days 1 and 8. The standard arm was cisplatin (40 mg/m2) weekly for 6 weeks with concurrent EBRT and brachytherapy as described for the experimental arm.- The primary end point was progression-free survival (PFS) at 3 years; however, the study found improvement in the experimental arm for PFS at 3 years (74.4%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 68%–79.8% vs. 65.0%; 95% CI, 58.5%–70.7%); overall PFS (hazard ratio [HR], 0.68; 95% CI, 0.49–0.95); and OS (HR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.49–0.95). Patients in the experimental arm had increased hematologic and nonhematologic grade 3 or 4 toxic effects, and two deaths in the experimental arm were possibly related to treatment.

A subgroup analysis showed an increased benefit in patients with a higher stage of disease (stages III–IVA vs. stage IIB), which suggested that the increased toxic effects of the experimental protocol may be justified for these patients.[

20 ] Additional investigation is needed to determine which aspect of the experimental arm led to improved survival (i.e., the addition of the weekly gemcitabine, the adjuvant chemotherapy, or both) and to determine quality of life during and after treatment, a condition that was omitted from the protocol.

Interstitial brachytherapy

For patients who complete EBRT and have bulky cervical disease such that standard brachytherapy cannot be placed anatomically, interstitial brachytherapy has been used to deliver adequate tumoricidal doses with an acceptable toxicity profile.[

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Several groups have investigated the role of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to convert patients who are conventional candidates for chemoradiation into candidates for radical surgery.[

EORTC-55994 (NCT00039338) randomly assigned patients with stages IB2, IIA2, and IIB cervical cancer to standard chemoradiation or neoadjuvant chemotherapy (with a cisplatin backbone for three cycles) followed by evaluation for surgery. With OS as the primary end point, this trial may delineate whether there is a role for neoadjuvant chemotherapy for this patient population.

Immunotherapy

Evidence (immunotherapy):

- KEYNOTE-A18 (NCT04221945) was a multicenter, phase III, randomized trial that included 1,060 women with newly diagnosed squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, or adenosquamous carcinoma of the cervix. Patients had stage IB2 or IIB node-positive disease or stage III to IVA disease and had received no prior treatment. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either chemoradiation therapy (with cisplatin) plus pembrolizumab (every 3 weeks for five cycles) or chemoradiation therapy plus placebo. All patients received maintenance therapy with pembrolizumab or placebo every 6 weeks for 15 cycles. All patients received brachytherapy, and 94% of patients had programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)–positive disease. The dual primary end points were PFS and OS. The median follow-up time was 17.9 months.[

28 ]- The 24-month OS rate was 87% in the pembrolizumab group and 81% in the placebo group (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.49–1.07).[

28 ][Level of evidence B1] - There was a statistically significant improvement in PFS (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.55–0.89). The 24-month PFS rate was 68% in the pembrolizumab group and 57% in the placebo group.

- Patients with stage III or IV disease had a greater improvement in PFS (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.42–0.80).

- The 24-month OS rate was 87% in the pembrolizumab group and 81% in the placebo group (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.49–1.07).[

Lymph Node Management

Patients who are surgically staged as part of a clinical trial and are found to have small-volume para-aortic nodal disease and controllable pelvic disease may be cured with pelvic and para-aortic radiation therapy.[

If postoperative EBRT is planned following surgery, extraperitoneal lymph–node sampling is associated with fewer radiation-induced complications than a transperitoneal approach.[

The resection of macroscopically involved pelvic nodes may improve rates of local control with postoperative radiation therapy.[

Current Clinical Trials

Use our

References:

- Perez CA, Grigsby PW, Nene SM, et al.: Effect of tumor size on the prognosis of carcinoma of the uterine cervix treated with irradiation alone. Cancer 69 (11): 2796-806, 1992.

- Lanciano RM, Won M, Hanks GE: A reappraisal of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system for cervical cancer. A study of patterns of care. Cancer 69 (2): 482-7, 1992.

- Lanciano RM, Martz K, Coia LR, et al.: Tumor and treatment factors improving outcome in stage III-B cervix cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 20 (1): 95-100, 1991.

- Monk BJ, Tewari KS, Koh WJ: Multimodality therapy for locally advanced cervical carcinoma: state of the art and future directions. J Clin Oncol 25 (20): 2952-65, 2007.