Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage

Plans through your employer

Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

Learn

Living or working abroad?

Childhood Liver Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

General Information About Childhood Liver Cancer

Liver cancer is a rare malignancy in children and adolescents and is divided into the following two major histological subgroups:

-

Hepatoblastoma .Well-differentiated fetal (pure fetal) histology .- Mixed epithelial and fetal histology.

Small cell undifferentiated histology hepatoblastoma and rhabdoid tumors of the liver .- Small cell undifferentiated hepatoblastoma (SMARCB1 positive).

- Rhabdoid tumor of liver (SMARCB1 negative).

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma .

Other less common histologies include the following:

-

Fibrolamellar carcinoma . -

Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver . -

Infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver . -

Vascular liver tumors . - Biliary rhabdomyosarcoma. For more information, see

Childhood Rhabdomyosarcoma Treatment .

Harmonization of Childhood Liver Cancer Data and Definitions

Historically, four major study groups have performed prospective clinical trials in children with liver tumors: The International Childhood Liver Tumors Strategy Group (previously known as Société Internationale d'Oncologie Pédiatrique–Epithelial Liver Tumor Study Group [SIOPEL]), the Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Onkologie und Hämatologie (Society for Paediatric Oncology and Haematology [GPOH]), the Japanese Study Group for Pediatric Liver Tumors (JPLT), and the Children's Oncology Group (COG), including its predecessor groups the Children's Cancer Group (CCG) and Pediatric Oncology Group (POG). These groups historically had disparate risk stratification categories, data elements that were monitored, and pathological and radiological definitions, making it difficult to compare outcomes across continents.

A collaborative effort among all four study groups collated their disparate data into a unified database called the Children's Hepatic Tumor International Collaboration (CHIC). The CHIC group analyzed clinical features and outcomes in a database that included 1,605 patients with hepatoblastoma treated in eight separate multicenter clinical trials, with central review of all tumor imaging and histological details.[

References:

- Czauderna P, Haeberle B, Hiyama E, et al.: The Children's Hepatic tumors International Collaboration (CHIC): Novel global rare tumor database yields new prognostic factors in hepatoblastoma and becomes a research model. Eur J Cancer 52: 92-101, 2016.

- Otte JB, Pritchard J, Aronson DC, et al.: Liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma: results from the International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) study SIOPEL-1 and review of the world experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer 42 (1): 74-83, 2004.

Cellular Classification of Childhood Liver Cancer

Liver tumors are rare in children. A definitive pathological diagnosis may be challenging because of the rarity of the tumor and the lack of a universal classification system before the Children's Hepatic Tumor International Collaboration (CHIC) harmonization efforts. Systematic central histopathological review of these tumors, performed as part of pediatric collaborative therapeutic protocols, has allowed the identification of histological subtypes with distinct clinical associations.

The Children's Oncology Group (COG) Liver Tumor Committee sponsored an International Pathology Symposium in 2011 to discuss the histopathology and classification of pediatric liver tumors (hepatoblastoma, in particular) and develop an International Pediatric Liver Tumors Consensus Classification that would be required for international collaborative projects. The results were published in 2014.[

For information about the histology of each childhood liver cancer subtype, see the following sections:

-

Hepatoblastoma . -

Hepatocellular carcinoma . -

Fibrolamellar carcinoma . -

Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver . -

Infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver . -

Vascular liver tumors .

References:

- López-Terrada D, Alaggio R, de Dávila MT, et al.: Towards an international pediatric liver tumor consensus classification: proceedings of the Los Angeles COG liver tumors symposium. Mod Pathol 27 (3): 472-91, 2014.

- Cho SJ, Ranganathan S, Alaggio R, et al.: Consensus classification of pediatric hepatocellular tumors: A report from the Children's Hepatic tumors International Collaboration (CHIC). Pediatr Blood Cancer : e30505, 2023.

Tumor Stratification by Imaging

A main treatment goal for children and adolescents with liver cancer is surgical extirpation of the primary tumor. Risk grouping depends heavily on factors determined by imaging that are related to safe surgical resection of the tumor, as well as the PRETEXT grouping. These imaging findings include the section or sections of the liver that are involved with the tumor and additional findings, called annotation factors, that impact surgical decision making and prognosis.

Risk stratification of children and adolescents with liver cancer involves the use of high-quality, cross-sectional imaging. Three-phase computed tomography scanning (noncontrast, arterial, and venous) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast agents are used. MRI with gadoxetate disodium, a gadolinium-based agent that is preferentially taken up and excreted by hepatocytes, is being used with increased frequency and may improve detection of multifocal disease.[

PRETEXT and POSTTEXT Group Definitions

The imaging grouping systems used to radiologically define the extent of liver involvement by the tumor are designated as the following:

- PRETEXT (PRE-Treatment EXTent of disease): The extent of liver involvement is defined before therapy.

- POSTTEXT (POST-Treatment EXTent of disease): The extent of liver involvement is defined in response to therapy.

PRETEXT

Major multicenter trial groups use PRETEXT as a central component of risk stratification schemes that guide treatment of hepatoblastoma. PRETEXT is based on the Couinaud eight-segment anatomical structure of the liver using cross-sectional imaging.

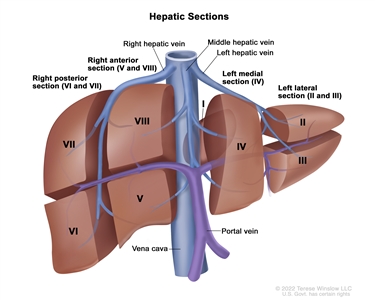

The PRETEXT system divides the liver into four parts, called sections. The left lobe of the liver consists of a lateral section (Couinaud segments I, II, and III) and a medial section (segment IV), whereas the right lobe consists of an anterior section (segments V and VIII) and a posterior section (segments VI and VII) (see

Figure 1. The liver is divided into four sections: the right posterior section, the right anterior section, the left medial section, and the left lateral section. Each section of the liver is further divided into segments: segments VI and VII make up the right posterior section, segments V and VIII make up the right anterior section, segment IV makes up the left medial section, and segments II and III make up the left lateral section. Segment I is found deep in the left side of the liver, in front of the inferior vena cava and behind the right, middle, and left hepatic veins.

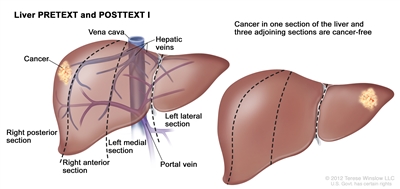

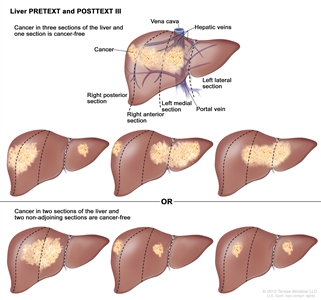

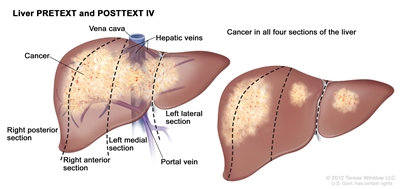

PRETEXT group assignment I, II, III, or IV is determined by the number of uninvolved sections of the liver. PRETEXT is further described by annotation factors. Annotation factors include findings that are important for surgical management and evidence of tumor extension beyond the hepatic parenchyma of the major sections, including metastatic disease. For detailed descriptions of the PRETEXT groups, see

Annotation factors identify the extent of tumor involvement of the major vessels and its effect on venous inflow and outflow. These factors provide critical knowledge for the surgeon and can affect surgical outcomes. At one time, definitions of gross vascular involvement used by the Children's Oncology Group (COG) and major liver surgery centers in the United States differed from those used by SIOPEL and in Europe. These differences have been resolved, and the new definitions are being used in an international trial.[

Although PRETEXT can be used to predict tumor resectability, it has limitations. It can be difficult to distinguish real invasion beyond the anatomical border of a given hepatic section from compression and displacement by the tumor, especially at diagnosis. Additionally, it can be difficult to distinguish between vessel encroachment and involvement, particularly if imaging is inadequate. The PRETEXT group assignment has a moderate degree of interobserver variability. In a report using data from the SIOPEL-1 study, the preoperative PRETEXT group aligned with postoperative pathological findings only 51% of the time, with overstaging in 37% of patients and understaging in 12% of patients.[

Because distinguishing PRETEXT group assignment is difficult, central review of imaging is critical and is generally performed in all major clinical trials. For patients not enrolled in clinical trials, expert radiological review should be considered in questionable cases in which the PRETEXT group assignment affects choice of treatment.

| PRETEXT and POSTTEXT Groups | Definition | Image | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a Adapted from Roebuck et al.[ |

|||

| I | One section involved; three adjoining sections are tumor free. |  |

|

| II | One or two sections involved; two adjoining sections are tumor free. |  |

|

| III | Two or three sections involved; one adjoining section is tumor free. |  |

|

| IV | Four sections involved. |  |

|

| Annotation Factors | Definition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| CT = computed tomography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; HU = Hounsfield unit. | |||

| a Adapted from Roebuck et al.[ |

|||

| b Additional details describing the annotation factors have been published.[ |

|||

| Vb | Venous involvement: Vascular involvement of the retrohepatic vena cava or involvement ofall three major hepatic veins (right, middle, and left). | ||

| V0 | Tumor within 1 cm. | ||

| V1 | Tumor abutting. | ||

| V2 | Tumor compressing or distorting. | ||

| V3 | Tumor ingrowth, encasement, or thrombus. | ||

| Pb | Portal involvement: Vascular involvement of the main portal vein and/orboth right and left portal veins. | ||

| P0 | Tumor within 1 cm. | ||

| P1 | Tumor abutting the main portal vein, the right and left portal veins, or the portal vein bifurcation. | ||

| P2 | Tumor compressing the main portal vein, the right and left portal veins, or the portal vein bifurcation. | ||

| P3 | Tumor ingrowth, encasement (>50% or >180 degrees), or intravascular thrombus within the main portal vein, the right and left portal veins, or the portal vein bifurcation. | ||

| Eb | Extrahepatic spread of disease. Any one of the following criteria is met: | ||

| E1 | Tumor crosses boundaries/tissue planes. | ||

| E2 | Tumor is surrounded by normal tissue more than 180 degrees. | ||

| E3 | Peritoneal nodules (not lymph nodes) are present so that there is at least one nodule measuring ≥10 mm or at least two nodules measuring ≥5 mm. | ||

| Mb | Distant metastases. Any one of the following criteria is met: | ||

| M1 | One noncalcified pulmonary nodule ≥5 mm in diameter. | ||

| M2 | Two or more noncalcified pulmonary nodules, each ≥3 mm in diameter. | ||

| M3 | Pathologically proven metastatic disease. | ||

| C | Tumor involving the caudate. | ||

| F | Multifocality. Two or more discrete hepatic tumors with normal intervening liver tissue. | ||

| Nb | Lymph node metastases. Any one of the following criteria is met: | ||

| N1 | Lymph node with short-axis diameter of >1 cm. | ||

| N2 | Portocaval lymph node with short-axis diameter >1.5 cm. | ||

| N3 | Spherical lymph node shape with loss of fatty hilum. | ||

| Rb | Tumor rupture. Free fluid in the abdomen or pelvis with one or more of the following findings of hemorrhage: | ||

| R1 | Internal complexity/septations within fluid. | ||

| R2 | High-density fluid on CT (>25 HU). | ||

| R3 | Imaging characteristics of blood or blood degradation products on MRI. | ||

| R4 | Heterogeneous fluid on ultrasound with echogenic debris. | ||

| R5 | Visible defect in tumor capsuleOR tumor cells are present within the peritoneal fluidOR rupture diagnosed pathologically in patients who have received an upfront resection. | ||

POSTTEXT

The POSTTEXT group is determined after patients receive chemotherapy. The greatest chemotherapy response, measured as decreases in tumor size and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level, occurs after the first two cycles of chemotherapy.[

Evans Surgical Staging for Childhood Liver Cancer

The COG/Evans staging system, based on operative findings and surgical resectability, was used for many years in the United States to group and determine treatment for children with liver cancer (see

| Evans Surgical Stage | Definition |

|---|---|

| Stage I | The tumor is completely resected. |

| Stage II | Microscopic residual tumor remains after resection. |

| Stage III | There are no distant metastases and at least one of the following is true: (1) the tumor is either unresectable or the tumor is resected with gross residual tumor; (2) there are positive extrahepatic lymph nodes. |

| Stage IV | There is distant metastasis, regardless of the extent of liver involvement. |

References:

- Meyers AB, Towbin AJ, Geller JI, et al.: Hepatoblastoma imaging with gadoxetate disodium-enhanced MRI--typical, atypical, pre- and post-treatment evaluation. Pediatr Radiol 42 (7): 859-66, 2012.

- Brown J, Perilongo G, Shafford E, et al.: Pretreatment prognostic factors for children with hepatoblastoma-- results from the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) study SIOPEL 1. Eur J Cancer 36 (11): 1418-25, 2000.

- Roebuck DJ, Aronson D, Clapuyt P, et al.: 2005 PRETEXT: a revised staging system for primary malignant liver tumours of childhood developed by the SIOPEL group. Pediatr Radiol 37 (2): 123-32; quiz 249-50, 2007.

- Towbin AJ, Meyers RL, Woodley H, et al.: 2017 PRETEXT: radiologic staging system for primary hepatic malignancies of childhood revised for the Paediatric Hepatic International Tumour Trial (PHITT). Pediatr Radiol 48 (4): 536-554, 2018.

- Aronson DC, Schnater JM, Staalman CR, et al.: Predictive value of the pretreatment extent of disease system in hepatoblastoma: results from the International Society of Pediatric Oncology Liver Tumor Study Group SIOPEL-1 study. J Clin Oncol 23 (6): 1245-52, 2005.

- Lovvorn HN, Ayers D, Zhao Z, et al.: Defining hepatoblastoma responsiveness to induction therapy as measured by tumor volume and serum alpha-fetoprotein kinetics. J Pediatr Surg 45 (1): 121-8; discussion 129, 2010.

- Venkatramani R, Stein JE, Sapra A, et al.: Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on resectability of stage III and IV hepatoblastoma. Br J Surg 102 (1): 108-13, 2015.

- Ortega JA, Krailo MD, Haas JE, et al.: Effective treatment of unresectable or metastatic hepatoblastoma with cisplatin and continuous infusion doxorubicin chemotherapy: a report from the Childrens Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol 9 (12): 2167-76, 1991.

- Douglass EC, Reynolds M, Finegold M, et al.: Cisplatin, vincristine, and fluorouracil therapy for hepatoblastoma: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 11 (1): 96-9, 1993.

- Ortega JA, Douglass EC, Feusner JH, et al.: Randomized comparison of cisplatin/vincristine/fluorouracil and cisplatin/continuous infusion doxorubicin for treatment of pediatric hepatoblastoma: A report from the Children's Cancer Group and the Pediatric Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 18 (14): 2665-75, 2000.

Treatment Option Overview for Childhood Liver Cancer

Many of the improvements in survival in childhood cancer have been made using new therapies that have attempted to improve on the best available, accepted therapy. Clinical trials in pediatrics are designed to compare potentially better therapy with therapy that is currently accepted as standard. This comparison may be done in a randomized study of two treatment arms or by evaluating a single new treatment and comparing the results with those previously obtained with standard therapy.

Because of the relative rarity of cancer in children, all children with liver cancer should be considered for a clinical trial if available. Treatment planning by a multidisciplinary team of cancer specialists with experience treating tumors of childhood is required to determine and implement optimal treatment.[

Surgery

Historically, complete surgical resection of the primary tumor has been essential for cure of malignant liver tumors in children.[

The three surgical options to treat primary pediatric liver cancer include the following:

- Initial surgical resection (alone or with adjuvant chemotherapy).

- Delayed surgical resection (with neoadjuvant chemotherapy).

- Orthotopic liver (cadaveric and living donor) transplant (most often with neoadjuvant chemotherapy).

The decision on which surgical approach to use (e.g., partial hepatectomy, extended resection, or transplant) depends on many factors, including the following:

- PRE-Treatment EXTent of disease (PRETEXT) group and POST-Treatment EXTent of disease (POSTTEXT) group.

- Size of the primary tumor.

- Presence of multifocal hepatic disease.

- Gross vascular involvement.

- Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels.

- Whether preoperative chemotherapy is likely to convert an unresectable tumor into a resectable tumor.

- Whether hepatic disease meets surgical and histopathological criteria for orthotopic liver transplant.

Timing of the surgical approach is critical. Surgeons who have experience performing pediatric liver resections and transplants are involved early in the decision-making process to determine optimal timing and extent of resection.

Early involvement, preferably at diagnosis, with an experienced pediatric liver surgeon is especially important in patients with PRETEXT group III or IV or involvement of major liver vessels (positive annotation factors V [venous] or P [portal]).[

Intraoperative ultrasonography may result in further delineation of tumor extent and location and can affect intraoperative management.[

If the tumor is determined to be unresectable, measures to reduce the tumor size to make a complete surgical resection possible need to be considered. These measures include preoperative intravenous chemotherapy, transarterial chemotherapy, or transarterial radioactive therapy. These efforts must be carefully coordinated with the surgical team to facilitate planning of resection. Prolonged chemotherapy can lead to unnecessary delays and, in rare cases, tumor progression. If the tumor can be completely excised by an experienced surgical team, less postoperative chemotherapy may be needed. Incomplete resection must be avoided because patients who undergo rescue transplants of incompletely resected tumors have an inferior outcome, compared with patients who undergo transplant as the primary surgical therapy.[

The approach taken by the Children's Oncology Group (COG) in North American clinical trials is to perform surgery initially when a complete resection can be done with a simple, negative-margin hemihepatectomy. The COG AHEP0731 (NCT00980460) trial studied the use of PRETEXT and POSTTEXT to determine the optimal approach and timing of surgery. POSTTEXT imaging grouping was performed after two and four cycles of chemotherapy to determine the optimal time for definitive surgery.[

Orthotopic liver transplant

Liver transplants have been associated with significant success in the treatment of children with unresectable hepatic tumors.[

Evidence (orthotopic liver transplant):

- The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database was queried for all patients younger than 18 years with a primary malignant liver tumor who underwent an orthotopic liver transplant between 1987 and 2012 (N = 544). The patients were diagnosed with hepatoblastoma (n = 376, 70%), hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 84, 15%), and other tumors (n = 84, 15%). Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma were older, more often hospitalized at the time of transplant, and more likely to receive a cadaveric organ than were patients with hepatoblastoma.[

27 ]- The 5-year patient survival rate was 73%, and the graft survival rate was 74% for the entire cohort, with most deaths resulting from malignancy. On multivariate analysis, independent predictors of 5-year patient and graft survival included the following:

- Diagnosis.

- For the study period of 1987 to 2012, the 5-year survival rate was 76% and the graft survival rate was 77% for patients with hepatoblastoma. The survival and graft survival rates were 63% for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

- For the study period of 2009 to 2012, the 3-year survival and graft survival rates were 84% for patients with hepatoblastoma. The survival and graft survival rates were 85% for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Transplant era.

- The death rate by hazard ratio was 1.0 for the period before 2002, 0.72 for the period of 2002 to 2009, and 0.54 for the period of 2009 to 2012.

- Medical condition at transplant.

- For hepatoblastoma patients, the survival rate by hazard ratio was 1.0 for hospitalized patients versus 1.81 for nonhospitalized patients at the time of transplant.

- For hepatocellular carcinoma patients, the survival rate by hazard ratio was 1.0 for hospitalized patients versus 1.92 for nonhospitalized patients.

- Patients hospitalized in the intensive care unit did not fare worse than patients not in the intensive care unit.

- Diagnosis.

- The 5-year patient survival rate was 73%, and the graft survival rate was 74% for the entire cohort, with most deaths resulting from malignancy. On multivariate analysis, independent predictors of 5-year patient and graft survival included the following:

- A report of 149 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma younger than 21 years who underwent transplants between 1987 and 2015 used detailed data collected at all U.S. pediatric transplant centers.[

19 ]- The 1-year graft survival rate of about 85% did not differ from the survival rate for patients with hepatoblastoma or biliary atresia. Survival rates continued to decline over time, from 85% at 1 year to 52% at 5 years and 43% at 10 years, a more dramatic decline than that seen for hepatoblastoma or biliary atresia.

- The survival after transplant did not differ from that of adults who underwent transplant for hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Of the patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, 22 received a diagnosis after transplant for medical cirrhotic disease such as tyrosinemia. They had a superior outcome, but it was not statistically significant compared with the rest of the patients.

- A review of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database and many single-institution series have reported results similar to the UNOS database study described above.[

11 ,20 ,21 ,22 ,28 ]; [25 ][Level of evidence C1] - In a three-institution study of children with hepatocellular carcinoma, the overall 5-year disease-free survival rate was approximately 60%.[

29 ] - In a study that used the Society of Pediatric Liver Transplantation (SPLIT) database to identify patients who underwent liver transplant between 2011 and 2019, the following was reported:[

30 ][Level of evidence C2]- The 3-year event-free survival (EFS) rate was 81% for patients with hepatoblastoma who received a transplant (n = 157).

- The 3-year EFS rate was 62% for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who received a transplant (n = 18).

- Of the patients who received a transplant to treat hepatoblastoma, 6.9% had PRETEXT II disease and 15.3% had POSTTEXT I/II disease.

- Tumor extent did not impact survival (P = NS).

- Patients who received transplants for salvage (n = 13) and patients who received transplants for primary hepatoblastoma had similar 3-year EFS rates (62% vs. 78%; P = NS).

- Among patients who received transplants for hepatocellular carcinoma, the 3-year EFS rate was poorer in older patients (38% for patients aged ≥8 years vs. 86% for patients aged <8 years; P < .001).

Application of the Milan criteria for UNOS selection of recipients of deceased donor livers is controversial.[

Cirrhosis is an underlying risk factor for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in children who suffer from certain diseases or conditions. These diseases include perinatally acquired hepatitis B, hepatorenal tyrosinemia, progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis, glycogen storage disease, Alagille syndrome, and other conditions. Improvements in screening methodology have allowed for earlier identification and treatment of some of these conditions, as well as monitoring for development of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nevertheless, because of the poor prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, liver transplant should be considered for diseases or conditions that have resulted in early findings of cirrhosis, before the development of liver failure or malignancy.[

Living-donor liver transplant for hepatic malignancy is more common in children than adults, and the outcome is similar to those undergoing cadaveric liver transplant.[

Surgical resection for metastatic disease

Surgical resection of metastatic disease is often recommended, but the rate of cure in children with hepatoblastoma has not been fully determined. Resection of metastases may be done for areas of locally invasive disease (e.g., diaphragm) and isolated brain metastases. Resection of pulmonary metastases should be considered if the number of metastases is limited.[

Radiofrequency ablation has also been used to treat oligometastatic hepatoblastoma when patients prefer to avoid surgical metastasectomy.[

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy regimens used in the treatment of hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma are described in their respective sections. Chemotherapy has been much more successful in the treatment of hepatoblastoma than in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma.[

The standard of care in the United States is preoperative chemotherapy when the tumor is unresectable and postoperative chemotherapy after complete resection, even if preoperative chemotherapy has already been given.[

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy, even in combination with chemotherapy, has not cured children with unresectable hepatic tumors. A study of 154 patients with hepatoblastoma showed that radiation therapy and/or second resection of positive margins may not be necessary in some patients with incompletely resected hepatoblastoma and microscopic residual tumor.[

Other Treatment Approaches

Other treatment approaches include the following:

- Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE): TACE is an image-guided, minimally invasive, nonsurgical procedure that is used to treat malignant lesions in the liver. The procedure uses a catheter to deliver both chemotherapy medication and embolization materials into the blood vessels that lead to the tumor. The arterial catheter route is image guided, most often via the hepatic artery, and perfusion of the tumor by the targeted artery may be confirmed by imaging before therapeutic injection. This procedure allows for the treatment of tumors that are not accessible with conventional surgery or radiation treatments. TACE has been used for patients with inoperable hepatoblastoma.[

47 ,48 ,49 ] This procedure has also been used in a few children to successfully shrink tumors to permit resections.[48 ] - Transarterial radioembolization (TARE): TARE is an image-guided, minimally invasive, nonsurgical procedure that delivers radiation therapy to treat tumors in the liver. This procedure delivers radioactive beads and blocks arterial flow within the tumor to keep the radiation inside the tumor. Glass or resin microspheres, coated most commonly with yttrium Y 90 (90Y), are delivered to the tumor via catheters placed in arteries that supply the tumor. Usually, the hepatic artery or its branches are used, but tumors may be partially supplied by parasitized surrounding vessels. Because of the risk of radiation delivery to the nearby lung, technetium Tc 99m microaggregated albumin imaging is performed with delivery via the catheter that is in place before the administration of radioactive beads to carefully measure radiation exposure to the lung. If calculations determine that lung exposure is unsafe, TARE is not pursued. TARE with 90Y has been used in children with hepatoblastoma (n = 2) and hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 2) who have unresectable tumors. After treatment with 90Y TARE, all tumors were completely resected.[

50 ][Level of evidence C3]; [51 ][Level of evidence C2] This approach has also been used for palliation in children with hepatocellular carcinoma.[52 ] For more information, seePrimary Liver Cancer Treatment . - High-intensity focused ultrasonography (HIFU): HIFU is a noninvasive treatment for a wide range of tumors and diseases. HIFU uses an ultrasound transducer, similar to the ones used for diagnostic imaging, but with much higher energy. The transducer focuses sound waves to generate heat at a single point in the body and destroy the target tissue. The tissue can get as hot as 66°C in only 20 seconds. This process is repeated as many times as necessary until the target tissue is destroyed. Magnetic resonance imaging is used to plan the treatment and monitor the amount of heat in real time. A combination of chemotherapy followed by TACE and HIFU showed promising results in China for children with PRETEXT III and PRETEXT IV malignant liver tumors, some of whom had resectable tumors but did not undergo surgery because of parent refusal.[

53 ]

References:

- Tiao GM, Bobey N, Allen S, et al.: The current management of hepatoblastoma: a combination of chemotherapy, conventional resection, and liver transplantation. J Pediatr 146 (2): 204-11, 2005.

- Czauderna P, Otte JB, Aronson DC, et al.: Guidelines for surgical treatment of hepatoblastoma in the modern era--recommendations from the Childhood Liver Tumour Strategy Group of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOPEL). Eur J Cancer 41 (7): 1031-6, 2005.

- Czauderna P, Mackinlay G, Perilongo G, et al.: Hepatocellular carcinoma in children: results of the first prospective study of the International Society of Pediatric Oncology group. J Clin Oncol 20 (12): 2798-804, 2002.

- Meyers RL, Czauderna P, Otte JB: Surgical treatment of hepatoblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 59 (5): 800-8, 2012.

- Aronson DC, Meyers RL: Malignant tumors of the liver in children. Semin Pediatr Surg 25 (5): 265-275, 2016.

- Murawski M, Weeda VB, Maibach R, et al.: Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Children: Does Modified Platinum- and Doxorubicin-Based Chemotherapy Increase Tumor Resectability and Change Outcome? Lessons Learned From the SIOPEL 2 and 3 Studies. J Clin Oncol 34 (10): 1050-6, 2016.

- Allan BJ, Wang B, Davis JS, et al.: A review of 218 pediatric cases of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Pediatr Surg 49 (1): 166-71; discussion 171, 2014.

- Becker K, Furch C, Schmid I, et al.: Impact of postoperative complications on overall survival of patients with hepatoblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62 (1): 24-8, 2015.

- D'Antiga L, Vallortigara F, Cillo U, et al.: Features predicting unresectability in hepatoblastoma. Cancer 110 (5): 1050-8, 2007.

- Lautz TB, Ben-Ami T, Tantemsapya N, et al.: Successful nontransplant resection of POST-TEXT III and IV hepatoblastoma. Cancer 117 (9): 1976-83, 2011.

- Fonseca A, Gupta A, Shaikh F, et al.: Extreme hepatic resections for the treatment of advanced hepatoblastoma: Are planned close margins an acceptable approach? Pediatr Blood Cancer 65 (2): , 2018.

- Fuchs J, Cavdar S, Blumenstock G, et al.: POST-TEXT III and IV Hepatoblastoma: Extended Hepatic Resection Avoids Liver Transplantation in Selected Cases. Ann Surg 266 (2): 318-323, 2017.

- Baertschiger RM, Ozsahin H, Rougemont AL, et al.: Cure of multifocal panhepatic hepatoblastoma: is liver transplantation always necessary? J Pediatr Surg 45 (5): 1030-6, 2010.

- Felsted AE, Shi Y, Masand PM, et al.: Intraoperative ultrasound for liver tumor resection in children. J Surg Res 198 (2): 418-23, 2015.

- Rossi G, Tarasconi A, Baiocchi G, et al.: Fluorescence guided surgery in liver tumors: applications and advantages. Acta Biomed 89 (9-S): 135-140, 2018.

- Shen Q, Liu X, Pan S, et al.: Effectiveness of indocyanine green fluorescence imaging in resection of hepatoblastoma. Pediatr Surg Int 39 (1): 181, 2023.

- Otte JB, Pritchard J, Aronson DC, et al.: Liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma: results from the International Society of Pediatric Oncology (SIOP) study SIOPEL-1 and review of the world experience. Pediatr Blood Cancer 42 (1): 74-83, 2004.

- Venkatramani R, Stein JE, Sapra A, et al.: Effect of neoadjuvant chemotherapy on resectability of stage III and IV hepatoblastoma. Br J Surg 102 (1): 108-13, 2015.

- Vinayak R, Cruz RJ, Ranganathan S, et al.: Pediatric liver transplantation for hepatocellular cancer and rare liver malignancies: US multicenter and single-center experience (1981-2015). Liver Transpl 23 (12): 1577-1588, 2017.

- Guiteau JJ, Cotton RT, Karpen SJ, et al.: Pediatric liver transplantation for primary malignant liver tumors with a focus on hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma: the UNOS experience. Pediatr Transplant 14 (3): 326-31, 2010.

- Malek MM, Shah SR, Atri P, et al.: Review of outcomes of primary liver cancers in children: our institutional experience with resection and transplantation. Surgery 148 (4): 778-82; discussion 782-4, 2010.

- Héry G, Franchi-Abella S, Habes D, et al.: Initial liver transplantation for unresectable hepatoblastoma after chemotherapy. Pediatr Blood Cancer 57 (7): 1270-5, 2011.

- Suh MY, Wang K, Gutweiler JR, et al.: Safety of minimal immunosuppression in liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma. J Pediatr Surg 43 (6): 1148-52, 2008.

- Zsíros J, Maibach R, Shafford E, et al.: Successful treatment of childhood high-risk hepatoblastoma with dose-intensive multiagent chemotherapy and surgery: final results of the SIOPEL-3HR study. J Clin Oncol 28 (15): 2584-90, 2010.

- Khan AS, Brecklin B, Vachharajani N, et al.: Liver Transplantation for Malignant Primary Pediatric Hepatic Tumors. J Am Coll Surg 225 (1): 103-113, 2017.

- Browne M, Sher D, Grant D, et al.: Survival after liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma: a 2-center experience. J Pediatr Surg 43 (11): 1973-81, 2008.

- Hamilton EC, Balogh J, Nguyen DT, et al.: Liver transplantation for primary hepatic malignancies of childhood: The UNOS experience. J Pediatr Surg : , 2017.

- McAteer JP, Goldin AB, Healey PJ, et al.: Surgical treatment of primary liver tumors in children: outcomes analysis of resection and transplantation in the SEER database. Pediatr Transplant 17 (8): 744-50, 2013.

- Reyes JD, Carr B, Dvorchik I, et al.: Liver transplantation and chemotherapy for hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular cancer in childhood and adolescence. J Pediatr 136 (6): 795-804, 2000.

- Boster JM, Superina R, Mazariegos GV, et al.: Predictors of survival following liver transplantation for pediatric hepatoblastoma and hepatocellular carcinoma: Experience from the Society of Pediatric Liver Transplantation (SPLIT). Am J Transplant 22 (5): 1396-1408, 2022.

- Otte JB: Should the selection of children with hepatocellular carcinoma be based on Milan criteria? Pediatr Transplant 12 (1): 1-3, 2008.

- de Ville de Goyet J, Meyers RL, Tiao GM, et al.: Beyond the Milan criteria for liver transplantation in children with hepatic tumours. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2 (6): 456-462, 2017.

- Khanna R, Verma SK: Pediatric hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 24 (35): 3980-3999, 2018.

- Sevmis S, Karakayali H, Ozçay F, et al.: Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma in children. Pediatr Transplant 12 (1): 52-6, 2008.

- Faraj W, Dar F, Marangoni G, et al.: Liver transplantation for hepatoblastoma. Liver Transpl 14 (11): 1614-9, 2008.

- Pire A, Tambucci R, De Magnée C, et al.: Living donor liver transplantation for hepatic malignancies in children. Pediatr Transplant 25 (7): e14047, 2021.

- Feusner JH, Krailo MD, Haas JE, et al.: Treatment of pulmonary metastases of initial stage I hepatoblastoma in childhood. Report from the Childrens Cancer Group. Cancer 71 (3): 859-64, 1993.

- Zsiros J, Brugieres L, Brock P, et al.: Dose-dense cisplatin-based chemotherapy and surgery for children with high-risk hepatoblastoma (SIOPEL-4): a prospective, single-arm, feasibility study. Lancet Oncol 14 (9): 834-42, 2013.

- Meyers RL, Katzenstein HM, Krailo M, et al.: Surgical resection of pulmonary metastatic lesions in children with hepatoblastoma. J Pediatr Surg 42 (12): 2050-6, 2007.

- O'Neill AF, Towbin AJ, Krailo MD, et al.: Characterization of Pulmonary Metastases in Children With Hepatoblastoma Treated on Children's Oncology Group Protocol AHEP0731 (The Treatment of Children With All Stages of Hepatoblastoma): A Report From the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 35 (30): 3465-3473, 2017.

- Yevich S, Calandri M, Gravel G, et al.: Reiterative Radiofrequency Ablation in the Management of Pediatric Patients with Hepatoblastoma Metastases to the Lung, Liver, or Bone. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 42 (1): 41-47, 2019.

- Weeda VB, Murawski M, McCabe AJ, et al.: Fibrolamellar variant of hepatocellular carcinoma does not have a better survival than conventional hepatocellular carcinoma--results and treatment recommendations from the Childhood Liver Tumour Strategy Group (SIOPEL) experience. Eur J Cancer 49 (12): 2698-704, 2013.

- Czauderna P, Lopez-Terrada D, Hiyama E, et al.: Hepatoblastoma state of the art: pathology, genetics, risk stratification, and chemotherapy. Curr Opin Pediatr 26 (1): 19-28, 2014.

- Schnater JM, Aronson DC, Plaschkes J, et al.: Surgical view of the treatment of patients with hepatoblastoma: results from the first prospective trial of the International Society of Pediatric Oncology Liver Tumor Study Group. Cancer 94 (4): 1111-20, 2002.

- Habrand JL, Nehme D, Kalifa C, et al.: Is there a place for radiation therapy in the management of hepatoblastomas and hepatocellular carcinomas in children? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 23 (3): 525-31, 1992.

- Wang PM, Chung NN, Hsu WC, et al.: Stereotactic body radiation therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: Optimal treatment strategies based on liver segmentation and functional hepatic reserve. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother 20 (6): 417-24, 2015 Nov-Dec.

- Xianliang H, Jianhong L, Xuewu J, et al.: Cure of hepatoblastoma with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 26 (1): 60-3, 2004.

- Malogolowkin MH, Stanley P, Steele DA, et al.: Feasibility and toxicity of chemoembolization for children with liver tumors. J Clin Oncol 18 (6): 1279-84, 2000.

- Hirakawa M, Nishie A, Asayama Y, et al.: Efficacy of preoperative transcatheter arterial chemoembolization combined with systemic chemotherapy for treatment of unresectable hepatoblastoma in children. Jpn J Radiol 32 (9): 529-36, 2014.

- Aguado A, Dunn SP, Averill LW, et al.: Successful use of transarterial radioembolization with yttrium-90 (TARE-Y90) in two children with hepatoblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 67 (9): e28421, 2020.

- Whitlock RS, Loo C, Patel K, et al.: Transarterial Radioembolization Treatment as a Bridge to Surgical Resection in Pediatric Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 43 (8): e1181-e1185, 2021.

- Hawkins CM, Kukreja K, Geller JI, et al.: Radioembolisation for treatment of pediatric hepatocellular carcinoma. Pediatr Radiol 43 (7): 876-81, 2013.

- Wang S, Yang C, Zhang J, et al.: First experience of high-intensity focused ultrasound combined with transcatheter arterial embolization as local control for hepatoblastoma. Hepatology 59 (1): 170-7, 2014.

Special Considerations for the Treatment of Children With Cancer

Cancer in children and adolescents is rare, although the overall incidence has slowly increased since 1975.[

- Primary care physicians.

- Pediatric surgeons.

- Transplant surgeons.

- Pathologists.

- Pediatric radiation oncologists.

- Pediatric medical oncologists and hematologists.

- Ophthalmologists.

- Rehabilitation specialists.

- Pediatric oncology nurses.

- Social workers.

- Child-life professionals.

- Psychologists.

- Nutritionists.

For specific information about supportive care for children and adolescents with cancer, see the summaries on

The American Academy of Pediatrics has outlined guidelines for pediatric cancer centers and their role in the treatment of children and adolescents with cancer.[

Dramatic improvements in survival have been achieved for children and adolescents with cancer. Between 1975 and 2020, childhood cancer mortality decreased by more than 50%.[

References:

- Smith MA, Seibel NL, Altekruse SF, et al.: Outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer: challenges for the twenty-first century. J Clin Oncol 28 (15): 2625-34, 2010.

- American Academy of Pediatrics: Standards for pediatric cancer centers. Pediatrics 134 (2): 410-4, 2014.

Also available online . Last accessed February 25, 2025. - Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC, et al.: Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer 120 (16): 2497-506, 2014.

- National Cancer Institute: NCCR*Explorer: An interactive website for NCCR cancer statistics. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Available online . Last accessed February 25, 2025. - Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute: SEER*Explorer: An interactive website for SEER cancer statistics. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Available online . Last accessed December 30, 2024.

Hepatoblastoma

Incidence

The annual incidence of hepatoblastoma in the United States has increased (more than doubled), from 0.8 (1975–1983) to 2.3 (2020) cases per 1 million children aged 19 years and younger.[

The age of onset of liver cancer in children is related to tumor histology. Hepatoblastomas usually occur before the age of 3 years, and approximately 90% of malignant liver tumors in children aged 4 years and younger are hepatoblastomas.[

Risk Factors

Conditions associated with an increased risk of hepatoblastoma are described in

| Associated Disorder | Clinical Findings |

|---|---|

| Aicardi syndrome[ |

For more information, see the |

| Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome[ |

For more information, see the |

| Familial adenomatous polyposis[ |

For more information, see the |

| Glycogen storage diseases I–IV[ |

Symptoms vary by individual disorder. |

| Low-birth-weight infants[ |

Preterm and small-for-gestation-age neonates. |

| Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome[ |

Macroglossia, macrosomia, renal and skeletal abnormalities, and increased risk of Wilms tumor. |

| Trisomy 18, other trisomies[ |

Trisomy 18: Microcephaly and micrognathia, clenched fists with overlapping fingers, and failure to thrive. Most patients (>90%) die in the first year of life. |

Aicardi syndrome

Aicardi syndrome is presumed to be an X-linked condition reported exclusively in females, leading to the hypothesis that an altered gene on the X chromosome causes lethality in males. The syndrome is classically defined as agenesis of the corpus callosum, chorioretinal lacunae, and infantile spasms, with a characteristic facies. Additional brain, eye, and costovertebral defects are often found.[

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and hemihyperplasia

The incidence of hepatoblastoma increases 1,000-fold to 10,000-fold in infants and children with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome.[

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome is most commonly caused by epigenetic changes and is sporadic. The syndrome may also be caused by genetic variants and be familial. Either mechanism can be associated with an increased incidence of embryonal tumors, including Wilms tumor and hepatoblastoma.[

To detect abdominal malignancies at an early stage, all children with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome or isolated hemihyperplasia undergo regular screening for multiple tumor types by abdominal ultrasonography.[

Familial adenomatous polyposis

Hepatoblastoma is associated with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Children in families that carry the APC gene have an 800-fold increased risk of hepatoblastoma. Screening for hepatoblastoma in members of families with FAP using ultrasonography and AFP levels is controversial because hepatoblastoma has been reported to occur in less than 1% of this group.[

Current evidence cannot rule out the possibility that predisposition to hepatoblastoma may be limited to a specific subset of APC variants. Another study of children with hepatoblastoma found a predominance of the variant in the 5' region of the gene, but some patients had variants closer to the 3' region.[

In the absence of APC germline variants, childhood hepatoblastomas do not have somatic variants in the APC gene. However, hepatoblastomas frequently have variants in the CTNNB1 gene, whose function is closely related to APC.[

Screening children predisposed to hepatoblastoma

An American Association for Cancer Research publication suggested that all children with genetic syndromes that lead to a risk of 1% or greater for developing hepatoblastoma undergo screening. This group includes patients with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, hemihyperplasia, Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome, and trisomy 18 syndrome. Screening is by abdominal ultrasonography and AFP determination every 3 months from birth (or diagnosis) through the fourth birthday, which will identify 90% to 95% of hepatoblastomas that develop in these children.[

Genomics of Hepatoblastoma

Molecular features of hepatoblastoma

Genomic findings related to hepatoblastoma include the following:

- The frequency of variants in hepatoblastoma, as determined by three groups using whole-exome sequencing, was very low (approximately three variants per tumor) in children younger than 5 years.[

31 ,32 ,33 ,34 ] A pediatric pan-cancer genomics study found that hepatoblastoma had the lowest gene variant rate among all childhood cancers studied.[35 ] - Hepatoblastoma is primarily a disease of WNT pathway activation. The primary mechanism for WNT pathway activation is CTNNB1 activating variants/deletions involving exon 3. CTNNB1 variants have been reported in more than 80% of cases.[

31 ,33 ,34 ,36 ,37 ] A less common cause of WNT pathway activation in hepatoblastoma is variants in APC associated with familial adenomatosis polyposis coli.[36 ] - NFE2L2 variants were identified in 10 of 174 (6%), 4 of 88 (5%), and 5 of 112 (4%) cases of hepatoblastoma in three studies.[

33 ,34 ,37 ] The presence of NFE2L2 variants was associated with a lower survival rate.[37 ] - Similar NFE2L2 variants have been found in many types of cancer, including hepatocellular carcinoma. These variants render NFE2L2 insensitive to KEAP1-mediated degradation, leading to activation of the NFE2L2-KEAP1 pathway, which activates resistance to oxidative stress and is believed to confer resistance to chemotherapy.

- TERT and TP53 variants, which are common in adults with hepatocellular carcinoma,[

38 ] are uncommon in children with hepatoblastoma.[31 ,33 ,34 ,36 ] Pediatric patients with TERT variants present with hepatoblastoma at a significantly older age, compared with patients without TERT variants (median age at diagnosis, approximately 10 years vs. 1.4 years).[37 ] - Uniparental disomy at 11p15.5 with loss of the maternal allele was reported in 6 of 15 cases of hepatoblastoma.[

39 ] This finding has been confirmed in genomic characterization studies, in which 30% to 40% of cases showed allelic imbalance at the 11p15 locus.[34 ,36 ,37 ]

Gene expression and epigenetic profiling have been used to identify biological subtypes of hepatoblastoma and to evaluate the prognostic significance of these subtypes.[

- A 16-gene expression signature divided hepatoblastoma cases into two subsets,[

37 ,40 ] C1 and C2. The C1 subtype included most of the well-differentiated fetal (pure fetal) histology cases. The C2 subtype showed a more immature pattern and was associated with higher rates of metastatic disease at diagnosis. In a study of 174 patients with hepatoblastoma, the C2 subtype was a significant predictor of poor outcome in multivariable analysis.[37 ] - A second research group also found that gene expression profiling could be used to identify subsets of hepatoblastoma with favorable versus unfavorable prognosis.[

33 ] The unfavorable prognosis group of patients showed elevated expression of genes associated with embryonic stem cell and progenitor cells (e.g., LIN28B, SALL4, and HMGA2). The favorable prognosis group of patients showed elevated expression of genes associated with liver differentiation (e.g., HNF1A). - A gene expression signature at chromosome 14q32 (e.g., DLK1) was identified, with a stronger expression signal being associated with higher risk of treatment failure.[

34 ] A strong 14q32 expression signature was also observed in fetal liver tissue, further supporting the concept that patients with hepatoblastoma who have tumors with biological characteristics that are similar to those of hepatic precursor cells have an inferior prognosis. - Epigenetic profiling of hepatoblastoma has been used to identify molecularly defined hepatoblastoma subtypes. Tumors from 113 patients with hepatoblastoma were evaluated using DNA methylation arrays. Two distinctive subtypes were identified, epigenetic cluster A and B (Epi-CA and Epi-CB).[

34 ] The methylation profile of Epi-CB resembled that of early embryonal/fetal phases of liver development. The methylation profile of Epi-CA was similar to that of late fetal or postnatal liver phases. Event-free survival was significantly lower for patients with the Epi-CB subtype than for those with the Epi-CA subtype.[34 ]

Delineating the clinical applications of these genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic profiling methods for the risk classification of patients with hepatoblastoma will require independent validation, which is one of the objectives of the Paediatric Hepatic International Tumour Trial (PHITT [NCT03017326]).

Diagnosis

Biopsy

A biopsy is always indicated to confirm the diagnosis of a pediatric liver tumor, except in the following circumstances:

- Infantile hepatic hemangioma. Biopsy is not indicated for patients with infantile hemangioma of the liver with classic findings on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). If the diagnosis is in doubt after high-quality imaging, a confirmatory biopsy is done.

- Focal nodular hyperplasia. Biopsy may not be indicated or may be delayed for patients with focal nodular hyperplasia with classic features on MRI using hepatocyte-specific contrast agent. If the diagnosis is in doubt, a confirmatory biopsy is done.

- Children's Oncology Group (COG) surgical guidelines (AHEP0731 [NCT00980460] appendix) recommend tumor resection at diagnosis without preoperative chemotherapy in children with PRE-Treatment EXTent of disease (PRETEXT) group I tumors and PRETEXT group II tumors with greater than 1 cm radiographic margin on the vena cava and middle hepatic and portal veins. Therefore, biopsy is not usually recommended in this circumstance.

- Infantile hepatic choriocarcinoma. In patients with infantile hepatic choriocarcinoma, which can be diagnosed by imaging and markedly elevated beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG), chemotherapy without biopsy is often indicated.[

41 ]

Tumor markers

The AFP and beta-hCG tumor markers are helpful in the diagnosis and management of liver tumors. Although AFP is elevated in most children with hepatic malignancies, it is not pathognomonic for a malignant liver tumor.[

Prognosis and Prognostic Factors

Prognosis

The 5-year overall survival (OS) rate for children with hepatoblastoma is 70%.[

Survival rates at 5 years, unrelated to annotation factors, were found to be the following:

- 90% for patients with PRETEXT I group tumors.

- 83% for patients with PRETEXT II group tumors.

- 73% for patients with PRETEXT III group tumors.

- 52% for patients with PRETEXT IV group tumors.

When each annotation factor was examined separately, regardless of the PRETEXT group or other annotation factors, the 5-year OS rates were found to be the following:

- 51% for patients with positive V (involvement of all three hepatic veins and/or inferior vena cava).

- 49% for patients with positive P (involvement of both right and left portal veins).

- 53% for patients with positive E (contiguous extrahepatic tumor).

- 52% for patients with positive F (multifocal).

- 51% for patients with positive R (tumor rupture).

- 41% for patients with positive M (distant metastasis).

For more information about PRETEXT grouping and annotation factors, see the

Hepatoblastoma prognosis by Evans surgical stage. Current study protocols use the PRETEXT staging for prognosis. The prognosis, based on Evans stage, is listed below. For more information, see the

- Stages I and II.

Approximately 20% to 30% of children with hepatoblastoma have stage I or II disease. Prognosis varies depending on the subtype of hepatoblastoma:

- Patients with well-differentiated fetal (previously termed pure fetal) histology tumors (4% of hepatoblastomas) have a 3- to 5-year OS rate of 100% with minimal or no chemotherapy, whether PRETEXT I, II, or III.[

50 ,51 ,52 ] - Patients with non–well-differentiated fetal histology, non–small cell undifferentiated stage I and II hepatoblastomas have a 3- to 4-year OS rate of 90% to 100% with adjuvant chemotherapy.[

50 ,51 ] - If any small cell undifferentiated elements are present in patients with stage I or II hepatoblastoma, the 3-year survival rate is 40% to 70%.[

50 ,53 ]

- Patients with well-differentiated fetal (previously termed pure fetal) histology tumors (4% of hepatoblastomas) have a 3- to 5-year OS rate of 100% with minimal or no chemotherapy, whether PRETEXT I, II, or III.[

- Stage III.

Approximately 50% to 70% of children with hepatoblastoma have stage III disease. The 3- to 5-year OS rate for these children is less than 70%.[

50 ,51 ] - Stage IV.

Approximately 10% to 20% of children with hepatoblastoma have stage IV disease. The 3- to 5-year OS rate for these children varies widely, from 20% to approximately 60%, based on published reports.[

50 ,51 ,54 ,55 ,56 ,57 ] Postsurgical stage IV is equivalent to any PRETEXT group with annotation factor M.[58 ,59 ,60 ]

Prognostic factors

Individual childhood cancer study groups have attempted to define the relative importance of a variety of prognostic factors present at diagnosis and in response to therapy.[

- Higher PRETEXT group.[

58 ] - Positive PRETEXT annotation factors:[

58 ]- V: Involvement of all three hepatic veins and/or intrahepatic inferior vena cava.

- P: Involvement of both left and right portal veins.

- E: Contiguous extrahepatic tumor extensions (e.g., diaphragm, adjacent organs).

- F: Multifocal tumors.

- R: Tumor rupture.

- M: Distant metastases, usually lung.

- Low AFP level (<100 ng/mL or 100–1,000 ng/mL to account for infants with elevated AFP levels).[

63 ] - Older age. Patients aged 3 to 7 years have a worse outcome in the PRETEXT IV group.[

58 ] Patients aged 8 years and older have a worse outcome than younger patients in all PRETEXT groups. In a subsequent report from the CHIC group, risk of an event increased with advancing age throughout all age cohorts.[64 ][Level of evidence C1] Increasing age attenuated the effect of other risk factors, including metastasis, AFP level less than 100 ng/mL, tumor rupture, and the presence of one annotation factor.In contrast, in the SIOPEL-2 and -3 studies, infants younger than 6 months had PRETEXT group, annotation factors, and outcomes similar to those of older children undergoing the same treatment.[

65 ][Level of evidence C1]

In the CHIC study, sex, prematurity, birth weight, and Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome had no effect on EFS.[

A multivariate analysis of these prognostic factors was published to help develop a new risk group classification for hepatoblastoma.[

Other studies observed the following factors that affected prognosis:

- PRETEXT group: In SIOPEL studies, having a low PRETEXT group at diagnosis (PRETEXT I, II, and III tumors) is a good prognostic factor, whereas PRETEXT IV is a poor prognostic factor.[

58 ] For more information, see theTumor Stratification by Imaging section. - Tumor stage: In COG studies, patients with classical hepatoblastoma histology and stage I tumors that were resected at diagnosis have a favorable outcome when treated with limited chemotherapy. Patients with tumors that have well-differentiated fetal histology have an excellent prognosis. These tumors are not generally treated with chemotherapy. Patients with tumors of other stages and histologies are treated more aggressively.[

58 ] - Treatment-related factors:

Chemotherapy: Chemotherapy often decreases the size and extent of hepatoblastoma tumors, allowing complete resection.[

51 ,54 ,66 ,67 ,68 ] Favorable response of the primary tumor to chemotherapy predicts its resectability, with favorable response defined as either a 30% decrease in tumor size by Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) or 90% or greater decrease in AFP levels. In turn, this favorable response predicted OS among all CHIC risk groups treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in the JPLT-2 Japanese national clinical trial.[69 ][Level of evidence B4]Surgery: Cure of hepatoblastoma requires gross tumor resection. Hepatoblastoma is most often unifocal, so resection may be possible. Most patients survive if a hepatoblastoma is completely removed. However, because of vascular or other involvement, less than one-third of patients have lesions that are amenable to complete resection at diagnosis.[

58 ] It is critically important that a child with probable hepatoblastoma be evaluated by a pediatric surgeon who is experienced in the techniques of extreme liver resection with vascular reconstruction. The child should also have access to a liver transplant program. In advanced tumors, surgical treatment of hepatoblastoma is a demanding procedure. Postoperative complications in high-risk patients decrease the OS rate.[70 ]Orthotopic liver transplant: Orthotopic liver transplant is an additional treatment option for patients whose tumor remains unresectable after preoperative chemotherapy.[

71 ,72 ] However, the presence of microscopic residual tumor at the surgical margin does not preclude a favorable outcome.[73 ,74 ] This outcome may result from additional courses of chemotherapy administered before or after resection.[66 ,67 ,73 ]For more information about the outcomes associated with specific chemotherapy regimens, see

Table 6 . - Tumor marker–related factors:

Ninety percent of children with hepatoblastoma and two-thirds of children with hepatocellular carcinoma exhibit elevated levels of the serum tumor marker AFP, which parallels disease activity. The level of AFP at diagnosis and rate of decrease in AFP levels during treatment are compared with the age-adjusted reference range. Lack of a significant decrease in AFP levels with treatment may predict a poor response to therapy.[

75 ] In an exploratory study of 34 children with hepatoblastoma, the rate of decrease in AFP and tumor volume, but not in RECIST I measurements, following two courses of treatment after diagnosis was predictive of EFS and OS.[76 ]Absence of elevated AFP levels at diagnosis (AFP <100 ng/mL) occurs in a small percentage of children with hepatoblastoma and appears to be associated with very poor prognosis, as well as with the small cell undifferentiated variant of hepatoblastoma.[

58 ] Some of these variants do not express SMARCB1 and may be considered rhabdoid tumors of the liver, which require alternative therapy. All small cell undifferentiated hepatoblastomas are tested for loss of SMARCB1 expression by immunohistochemistry to determine those that should be treated as a hepatoblastoma versus those that should be treated as rhabdoid tumors of the liver.[50 ,53 ,56 ,57 ,77 ,78 ]Beta-hCG levels may also be elevated in children with hepatoblastoma or hepatocellular carcinoma, which may result in isosexual precocity in boys.[

45 ,46 ] - Tumor histology:

For more information, see the

Histology section in the Hepatoblastoma section.

Other variables have been proposed to be poor prognostic factors, but their significance has been difficult to define. In the SIOPEL-1 study, a multivariate analysis of prognosis after positive response to chemotherapy showed that only one variable, PRETEXT group, predicted OS, while metastasis and PRETEXT group predicted EFS.[

Histology

Hepatoblastoma arises from precursors of hepatocytes and can have several morphologies, including the following:[

- Small cells that reflect neither epithelial nor stromal differentiation. It is critical to discriminate between small cell undifferentiated hepatoblastoma expressing SMARCB1 and rhabdoid tumor of the liver, which lacks the SMARCB1 gene and SMARCB1 expression. Both diseases may share similar histology. Optimal treatment of rhabdoid tumor of the liver and small cell undifferentiated hepatoblastoma may require different approaches and different chemotherapy. For a more extensive discussion on the differences of these two diseases, see the

Small cell undifferentiated histology hepatoblastoma and rhabdoid tumors of the liver section. - Embryonal epithelial cells resembling the liver epithelium at 6 to 8 weeks of gestation.

- Well-differentiated fetal hepatocytes morphologically indistinguishable from normal fetal liver cells.

Most often the tumor consists of a mixture of epithelial hepatocyte precursors. About 20% of tumors have stromal derivatives such as osteoid, chondroid, and rhabdoid elements. Occasionally, neuronal, melanocytic, squamous, and enteroendocrine elements are found. The following histological subtypes have clinical relevance:

-

Well-differentiated fetal (pure fetal) histology hepatoblastoma . - Mixed fetal and embryonal epithelial cells.

-

Small cell undifferentiated histology hepatoblastoma and rhabdoid tumors of the liver .- Small cell undifferentiated hepatoblastoma (SMARCB1 positive).

- Rhabdoid tumor of liver (SMARCB1 negative).

Well-differentiated fetal (pure fetal) histology hepatoblastoma

An analysis of patients with initially resected hepatoblastoma tumors (before receiving chemotherapy) has suggested that patients with well-differentiated fetal (previously termed pure fetal) histology tumors have a better prognosis than patients with an admixture of more primitive and rapidly dividing embryonal components or other undifferentiated tissues. Studies have reported the following:

- A study of patients with hepatoblastoma and well-differentiated fetal histology tumors observed the following:[

51 ]- The survival rate was 100% for patients who received four doses of single-agent doxorubicin. This finding suggested that patients with well-differentiated fetal histology tumors might not need chemotherapy after complete resection.[

81 ,82 ]

- The survival rate was 100% for patients who received four doses of single-agent doxorubicin. This finding suggested that patients with well-differentiated fetal histology tumors might not need chemotherapy after complete resection.[

- In a COG study (COG-P9645), 16 patients with well-differentiated fetal histology hepatoblastoma with two or fewer mitoses per 10 high-power fields were not treated with chemotherapy. Retrospectively, their PRETEXT groups were group I (n = 4), group II (n = 6), and group III (n = 2).[

52 ]- The survival rate was 100%.

- All 16 patients were alive with no evidence of disease at a median follow-up of 4.9 years (range, 9 months to 9.2 years).

Thus, complete resection of a well-differentiated fetal hepatoblastoma may preclude the need for chemotherapy.

Small cell undifferentiated histology hepatoblastoma and rhabdoid tumors of the liver

Small cell undifferentiated hepatoblastoma (SMARCB1 retained) is an uncommon hepatoblastoma variant. Histologically, small cell undifferentiated hepatoblastoma is typified by a diffuse population of small cells with scant cytoplasm resembling neuroblasts.[

Small cell undifferentiated histology hepatoblastoma and rhabdoid tumors of the livers can be distinguished by the following characteristic abnormalities:

- Chromosomal abnormalities. These abnormalities in rhabdoid tumors include translocations involving a breakpoint on chromosome 22q11 and homozygous deletion at the chromosome 22q12 region that harbors the SMARCB1 gene.[

84 ,85 ] - Lack of SMARCB1 expression. Lack of detection of SMARCB1 by immunohistochemistry is characteristic of malignant rhabdoid tumors.[

84 ]

Historically, small cell undifferentiated hepatoblastoma was reported to occur at a younger age (6–10 months) than other cases of hepatoblastoma [

The Paediatric Hepatic International Tumour Trial (PHITT) designates any childhood liver tumor as rhabdoid tumor of the liver if it contains cells that lack SMARCB1 expression. Patients with SMARCB1-negative tumors, which are presumed to be related to rhabdoid tumors, may not be enrolled in the international trial, which addresses treatment of hepatoblastoma that includes small cell undifferentiated histology, hepatocellular carcinoma, and hepatic malignancy of childhood, not otherwise specified (NOS), but not rhabdoid tumor of the liver. In this trial, all patients with histology consistent with pure small cell undifferentiated hepatoblastoma, as assessed by the institutional pathologist, are required to have testing for SMARCB1 by immunohistochemistry according to the practices at the institution. In addition, presence of a blastemal component indicates conventional hepatoblastoma.[

A characteristic shared by both small cell undifferentiated hepatoblastoma and malignant rhabdoid tumor is the poor prognosis associated with each.[

- In 2009, the results of a study of 11 young children with low AFP levels and small cell morphology were reported. Ten children died of disease progression, and one child died of complications. Six of six children tested were SMARCB1 negative, but only one child had any rhabdoid morphology. This finding suggests that many or all liver tumors with small cell morphology and very low AFP levels in young children may be rhabdoid tumors of the liver. These tumors have a poor prognosis that is associated with the driver variant.[

84 ] - A single-institution study of seven children with small cell morphology liver tumors found that all retained expression of SMARCB1. Six children survived, and one child died of complications from liver transplant.[

88 ] - A study of 23 liver tumors from the Kiel tumor bank found 12 tumors with small cell morphology. Nine tumors had malignant rhabdoid tumor classic histology, and two tumors had mixed small cell and rhabdoid histologies. Outcomes were not provided, but it was noted that rhabdoid brain tumors had small cell, not classic, rhabdoid histology.[

89 ] - In a single-institution study of six children with SMARCB1-negative liver tumors, two children with small cell morphology died. The remaining four children with classic rhabdoid histology were not treated with cisplatin-based therapy; three children survived, and one child died of complications from transplant.[

90 ] - A report from the COG AHEP0731 (NCT00980460) trial identified 35 of 177 evaluable patients (19%) with small cell undifferentiated hepatoblastoma confirmed by central review.[

86 ] SMARCB1 nuclear expression was retained in 33 of 35 patients. Unlike previous reports, the presence of small cell undifferentiated histology did not correlate with age, sex, or AFP levels at diagnosis. The 5-year EFS rates for patients with low-, intermediate-, and high-risk small cell undifferentiated hepatoblastoma were 86% (95% confidence interval [CI], 33%–98%), 81% (95% CI, 51%–92%), and 29% (95% CI, 4%–81%), respectively. The 5-year EFS rates for patients with low-, intermediate-, and high-risk hepatoblastoma without small cell undifferentiated histology were 87% (95% CI, 72%–95%), 88% (95% CI, 79%–95%), and 55% (95% CI, 33%–74%); P = .17), respectively. In this trial, concordance between local and central review was poor, and they agreed in only 9 of 35 cases (26%). All tumors were tested for SMARCB1 expression by immunohistochemistry. In this study, hepatoblastoma that would otherwise be considered very low risk or low risk was upgraded to intermediate risk if any small cell undifferentiated elements were found. For more information, seeTable 5 .

The outcomes of the CHIC trial of childhood liver tumors may clarify some of the questions regarding these different histological and genetic findings.

Risk Stratification

There are significant differences among childhood cancer study groups in risk stratification used to determine treatment, making it difficult to compare results of the different treatments.

| | COG (AHEP-0731) | SIOPEL (SIOPEL-3, -3HR, -4, -6) | GPOH | JPLT (JPLT-2 and -3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFP = alpha-fetoprotein; COG = Children's Oncology Group; GPOH = Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Onkologie und Hämatologie (Society for Paediatric Oncology and Haematology); JPLT = Japanese Study Group for Pediatric Liver Tumor; PRETEXT = PRE-Treatment EXTent of disease; SIOPEL = International Childhood Liver Tumors Strategy Group. | ||||

| a Adapted from Czauderna et al.[ |

||||

| b For more information about the annotations used in PRETEXT, see |

||||

| c The COG and PRETEXT definitions of vascular involvement differ. | ||||

| Very low risk | PRETEXT I or II; well-differentiated fetal histology; primary resection at diagnosis | |||

| Low risk/standard risk | PRETEXT I or II of any histology with primary resection at diagnosis | PRETEXT I, II, or III | PRETEXT I, II, or III | PRETEXT I, II, or III |

| Intermediate riskb | PRETEXT II, III, or IV unresectable at diagnosis; or V+c, P+, E+ | PRETEXT IV or any PRETEXT with rupture; or N1, P2, P2a, V3, V3a; or multifocal | ||

| High riskb | Any PRETEXT with M+; AFP level <100 ng/mL | Any PRETEXT; V+, P+, E+, M+; AFP level <100 ng/mL; tumor rupture | Any PRETEXT with V+, E+, P+, M+ or multifocal | Any PRETEXT with M1 or N2; or AFP level <100 ng/mL |

International risk classification model

The CHIC group developed a novel risk stratification system for use in international clinical trials on the basis of prognostic features present at diagnosis. CHIC unified the disparate definitions and staging systems used by pediatric cooperative multicenter trial groups, enabling the comparison of studies conducted by heterogeneous groups in different countries.[

Based on the initial univariate analysis of the data combined with historical clinical treatment patterns and data from previous large clinical trials, five backbone groups were selected, which allowed for further risk stratification. Subsequent multivariate analysis on the basis of these backbone groups defined the following clinical prognostic factors: PRETEXT group (I, II, III, or IV), presence of metastasis (yes or no), and AFP (≤100 ng/mL). The backbone groups are as follows:[

- Backbone 1: PRETEXT I/II, not metastatic, AFP greater than 100 ng/mL.

- Backbone 2: PRETEXT III, not metastatic, AFP greater than 100 ng/mL.

- Backbone 3: PRETEXT IV, not metastatic, AFP greater than 100 ng/mL.

- Backbone 4: Any PRETEXT group, metastatic disease at diagnosis, AFP greater than 100 ng/mL.

- Backbone 5: Any PRETEXT group, metastatic or not, AFP less than or equal to 100 ng/mL at diagnosis.

Other diagnostic factors (e.g., age) were queried for each of the backbone categories, including the presence of at least one of the following PRETEXT annotations (defined as VPEFR+, see

- V: Involvement of vena cava or all three hepatic veins, or both.

- P: Involvement of portal bifurcation or both right and left portal veins, or both.

- E: Extrahepatic contiguous tumor extension.

- F: Multifocal liver tumor.

- R: Tumor rupture at diagnosis.

An assessment of surgical resectability at diagnosis was added for PRETEXT I and II patients. Patients in each of the five backbone categories were stratified on the basis of backwards stepwise elimination multivariable analysis of additional patient characteristics, including age and presence or absence of PRETEXT annotation factors (V, P, E, F, and R). Each of these subcategories received one of four risk designations (very low, low, intermediate, or high). The result of the multivariate analysis was used to assign patients to very low-, low-, intermediate-, and high-risk categories, as shown in

Figure 2. Risk stratification trees for the Children's Hepatic tumors International Collaboration—Hepatoblastoma Stratification (CHIC-HS). Very low-risk group and low-risk group are separated only by their resectability at diagnosis, which has been defined by international consensus as part of the surgical guidelines for the collaborative trial, Paediatric Hepatic International Tumour Trial (PHITT). Separate risk stratification trees are used for each of the four PRETEXT groups. AFP = alpha-fetoprotein. M = metastatic disease. PRETEXT = PRETreatment EXTent of disease. Reprinted from The Lancet Oncology, Volume 18, Meyers RL, Maibach R, Hiyama E, Häberle B, Krailo M, Rangaswami A, Aronson DC, Malogolowkin MH, Perilongo G, von Schweinitz D, Ansari M, Lopez-Terrada D, Tanaka Y, Alaggio R, Leuschner I, Hishiki T, Schmid I, Watanabe K, Yoshimura K, Feng Y, Rinaldi E, Saraceno D, Derosa M, Czauderna P, Risk-stratified staging in paediatric hepatoblastoma: a unified analysis from the Children's Hepatic tumors International Collaboration, Pages 122–131, Copyright (2017), with permission from Elsevier.

Treatment of Hepatoblastoma

Treatment options for newly diagnosed hepatoblastoma depend on the following:

- Whether the cancer is resectable at diagnosis.

- The tumor histology.

- How the cancer responds to chemotherapy.

- Whether the cancer has metastasized.

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy has resulted in a survival rate of more than 90% for children with PRETEXT and POST-Treatment EXTent (POSTTEXT) group I and II resectable disease before or after chemotherapy.[

Chemotherapy regimens used in the treatment of hepatoblastoma and their respective outcomes are described in

| Study | Chemotherapy Regimen | Number of Patients | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AFP = alpha-fetoprotein; C5V = cisplatin, fluorouracil (5-FU), and vincristine; CARBO = carboplatin; CCG = Children's Cancer Group; CDDP = cisplatin; CITA = pirarubicin-cisplatin; COG = Children's Oncology Group; DOXO = doxorubicin; EFS = event-free survival; GPOH = Gesellschaft für Pädiatrische Onkologie und Hämatologie (Society for Paediatric Oncology and Haematology); H+ = rupture or intraperitoneal hemorrhage; HR = high risk; IFOS = ifosfamide; IPA = ifosfamide, cisplatin, and doxorubicin; ITEC = ifosfamide, pirarubicin, etoposide, and carboplatin; JPLT = Japanese Study Group for Pediatric Liver Tumor; LR = low risk; NR = not reported; OS = overall survival; PLADO = cisplatin and doxorubicin; POG = Pediatric Oncology Group; PRETEXT = PRE-Treatment EXTent of disease; SIOPEL = International Childhood Liver Tumors Strategy Group; SR = standard risk; SUPERPLADO = cisplatin, doxorubicin, and carboplatin; THP = tetrahydropyranyl-adriamycin (pirarubicin); VP = vinorelbine and cisplatin; VPE+ = venous, portal, and extrahepatic involvement; VP16 = etoposide. | |||

| a Adapted from Czauderna et al.,[ |

|||

| b Study closed early because of inferior results in the CDDP/CARBO arm. | |||

| INT0098 (CCG/POG) 1989–1992 | C5V vs. CDDP/DOXO | Stage I/II: 50 | 4-Year EFS/OS: |

| I/II = 88%/100% vs. 96%/96% | |||

| Stage III: 83 | III = 60%/68% vs. 68%/71% | ||

| Stage IV: 40 | IV = 14%/33% vs. 37%/42% | ||

| P9645 (COG) b 1999–2002 | C5V vs. CDDP/CARBO | Stage III: 38 | 3-year EFS/OS: |

| III/IV: C5V = 60%/74%; CDDP/CARBO = 38%/54% | |||

| Stage IV: 50 | |||

| AHEP0731 (COG) 2010–2014[ |

LR: C5V (2 cycles) | LR (stage I/II): 49 | 5-year EFS: 88%;5-year OS: 91% |

| HB 94 (GPOH) 1994–1997 | I/II: IFOS/CDDP/DOXO | Stage I: 27 | 4-Year EFS/OS: |

| I = 89%/96% | |||

| Stage II: 3 | II = 100%/100% | ||

| III/IV: IFOS/CDDP/DOXO + VP/CARBO | Stage III: 25 | III = 68%/76% | |

| Stage IV: 14 | IV = 21%/36% | ||

| HB 99 (GPOH) 1999–2004 | SR: IPA | SR: 58 | 3-Year EFS/OS: |

| SR = 90%/88% | |||

| HR: CARBO/VP16 | HR: 42 | HR = 52%/55% | |

| SIOPEL-2 1994–1998 | SR: PLADO | PRETEXT I: 6 | 3-Year EFS/OS: |

| SR: 73%/91% | |||

| PRETEXT II: 36 | |||

| PRETEXT III: 25 | |||

| HR: CDDP/CARBO/DOXO | PRETEXT IV: 21 | HR: IV = 48%/61% | |

| Metastases: 25 | HR: metastases = 36%/44% | ||

| SIOPEL-3 1998–2006 | SR: CDDP vs. PLADO | SR: PRETEXT I: 18 | 3-Year EFS/OS: |

| SR: CDDP = 83%/95%; PLADO = 85%/93% | |||

| PRETEXT II: 133 | |||

| PRETEXT III: 104 | |||

| HR: SUPERPLADO | HR: PRETEXT IV: 74 | HR: Overall = 65%/69% | |

| VPE+: 70 | |||

| Metastases: 70 | Metastases = 57%/63% | ||

| AFP <100 ng/mL: 12 | |||

| SIOPEL-4 2005–2009 | HR: Block A: Weekly; CDDP/3 weekly DOXO; Block B: CARBO/DOXO | PRETEXT I: 2 | 3-Year EFS/OS: |

| All HR = 76%/83% | |||