Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage

Plans through your employer

Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

Learn

Living or working abroad?

Childhood Liver Cancer Treatment: Treatment - Patient Information [NCI]

Hepatoblastoma

Hepatoblastoma is a cancer that forms in the tissues of the liver. It is the most common type of childhood liver cancer and usually affects children younger than 3 years of age.

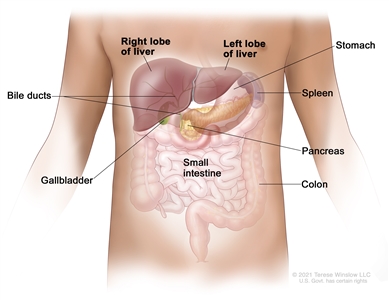

The liver is one of the largest organs in the body. It has two lobes and fills the upper right side of the abdomen inside the rib cage. Three of the many important functions of the liver are:

- to make bile to help digest fats from food

- to store glycogen (sugar), which the body uses for energy

- to filter harmful substances from the blood so they can be passed from the body in stools and urine

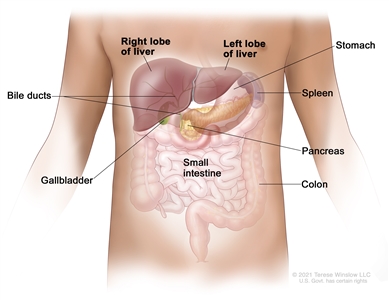

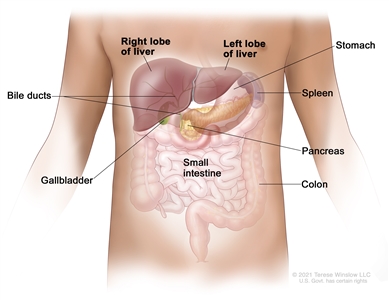

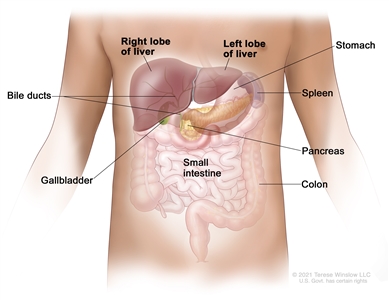

Anatomy of the liver. The liver is in the upper abdomen near the stomach, intestines, gallbladder, and pancreas. The liver has a right lobe and a left lobe. Each lobe is divided into two sections (not shown).

In hepatoblastoma, the histology (how the cancer cells look under a microscope) affects the way the cancer is treated. The histology for hepatoblastoma includes:

- well-differentiated fetal (pure fetal) histology

- small cell undifferentiated histology hepatoblastoma and rhabdoid tumors of the liver

- mixed epithelial and fetal histology (non–well-differentiated fetal histology, non-small cell undifferentiated histology)

Causes and risk factors for hepatoblastoma

Hepatoblastoma is caused by certain changes in the way the liver cells function, especially how they grow and divide into new cells. Often, the exact cause of these changes is unknown. Learn more about how cancer develops at

A risk factor is anything that increases the chance of getting a disease. Not every child with one or more of these risk factors will develop hepatoblastoma. And it will develop in some children who don't have a known risk factor.

The following syndromes or conditions are risk factors for hepatoblastoma:

- Aicardi syndrome

- Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome

- hemihyperplasia

- familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP)

- glycogen storage disease

- premature birth with a very low weight at birth

- Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome

- certain genetic changes, such as trisomy 18

Talk with your child's doctor if you think your child may be at risk.

Monitoring children at risk of hepatoblastoma

Children with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, hemihyperplasia, Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome, and trisomy 18 may have tests done to check for cancer before any symptoms appear. These tests may help find cancer early and improve your child's chance of survival.

Children at risk of developing hepatoblastoma have an abdominal ultrasound exam every 3 months from birth (or diagnosis of a risk factor) until they are 4 years old. They also have blood tests to check the level of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP).

Symptoms of hepatoblastoma

Children may not have symptoms of hepatoblastoma until the tumor has grown bigger. It's important to check with your child's doctor if your child has:

- a lump in the abdomen

- swelling in the abdomen

- pain in the abdomen

- weight loss for no known reason

- loss of appetite

- nausea and vomiting

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than hepatoblastoma. The only way to know is for your child to see a doctor.

Tests to diagnose hepatoblastoma

If your child has symptoms that suggest hepatoblastoma, the doctor will need to find out if these are due to cancer or another problem. The doctor will ask when the symptoms started and how often your child has been having them. They will also ask about your child's personal and family medical history and do a physical exam. Based on these results, the doctor may recommend other tests. If your child is diagnosed with hepatoblastoma, the results of these tests will also help you and your child's doctor plan treatment.

The tests used to diagnose hepatoblastoma may include:

Serum tumor marker test

Serum tumor marker tests measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by organs, tissues, or tumor cells in the body. Certain substances are linked to specific types of cancer when found in increased levels in the blood. These are called tumor markers. The blood of children who have liver cancer may have increased amounts of a hormone called beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) or a protein called AFP. Other cancers, benign liver tumors, and certain noncancer conditions, including cirrhosis and hepatitis, can also increase AFP levels.

SMARCB1gene testing

SMARCB1 gene testing is a laboratory test in which a sample of blood or tissue is tested for certain changes in the SMARCB1 gene.

Complete blood count (CBC)

A CBC checks a sample of blood for:

- the number of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets

- the amount of hemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen) in the red blood cells

- the portion of the blood sample made up of red blood cells

Liver function tests

Liver function tests measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by the liver. A higher-than-normal amount of a substance can be a sign of liver damage or cancer.

Blood chemistry studies

Blood chemistry studies measure the amounts of certain substances, such as bilirubin or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), released into the blood by organs and tissues in the body. An unusual amount of a substance can be a sign of disease.

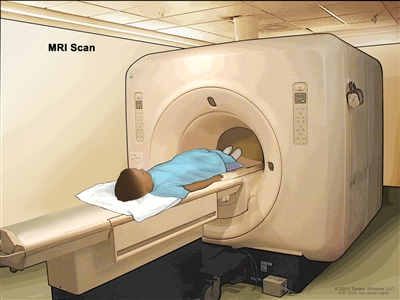

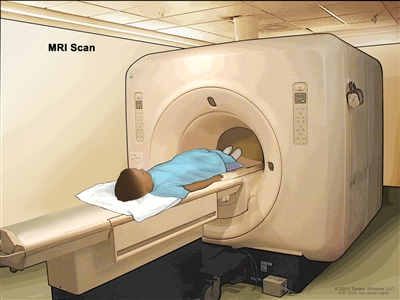

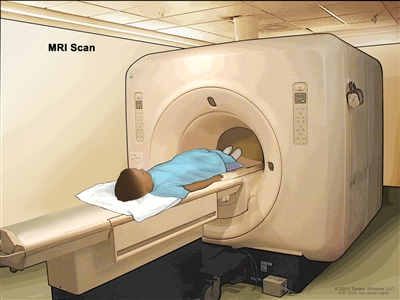

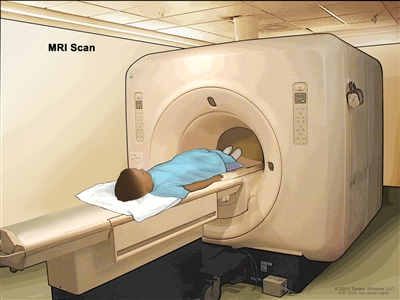

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium

MRI uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the liver. A substance called gadolinium is injected into a vein. The gadolinium collects around the cancer cells so they show up brighter in the picture. This procedure is also called nuclear MRI.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The child lies on a table that slides into the MRI machine, which takes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. The positioning of the child on the table depends on the part of the body being imaged.

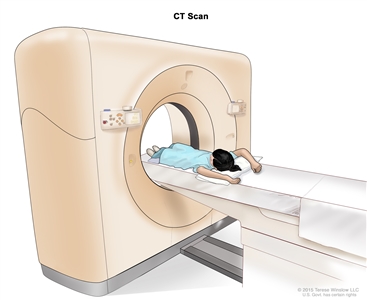

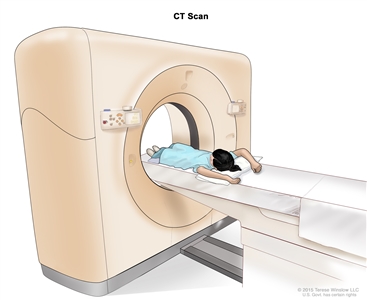

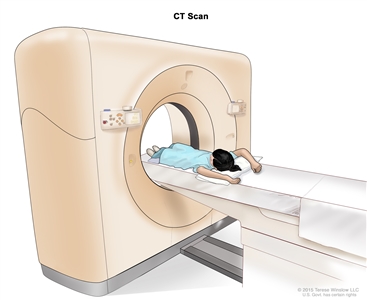

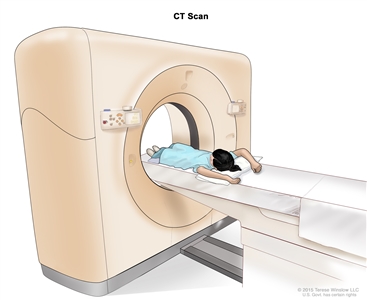

CT scan (CAT scan)

A CT scan uses a computer linked to an x-ray machine to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, taken from different angles. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

A CT scan of the chest and abdomen is usually done to help diagnose childhood liver cancer.

Learn more about

Computed tomography (CT) scan. The child lies on a table that slides through the CT scanner, which takes a series of detailed x-ray pictures of areas inside the body.

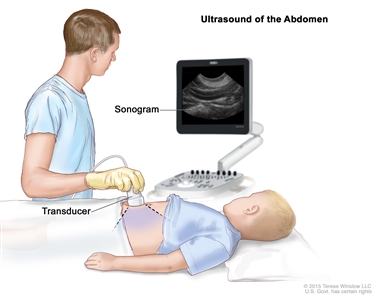

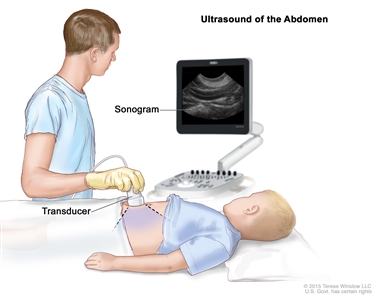

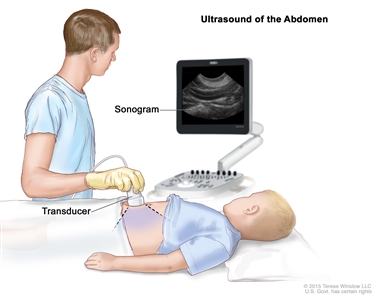

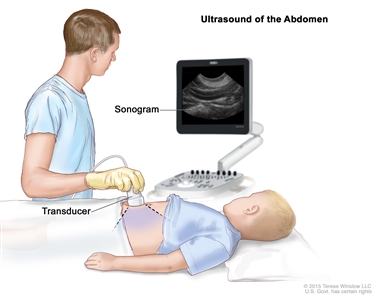

Ultrasound exam

An ultrasound exam is a procedure in which high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) are bounced off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. An ultrasound exam of the abdomen to check the large blood vessels is usually done to help diagnose childhood liver cancer.

Abdominal ultrasound. An ultrasound transducer connected to a computer is pressed against the skin of the abdomen. The transducer bounces sound waves off internal organs and tissues to make echoes that form a sonogram (computer picture).

Chest x-ray

An x-ray is a type of high-energy radiation that can go through the body and make pictures. A chest x-ray is one that makes pictures of the lungs.

Biopsy

Biopsy is a procedure in which a sample of tissue is removed from the tumor so that a pathologist can view it under a microscope to check for cancer. The doctor may remove as much tumor as safely possible during the same biopsy procedure.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry uses antibodies to check for certain antigens (markers) in a sample of a patient's tissue. The antibodies are usually linked to an enzyme or a fluorescent dye. After the antibodies bind to a specific antigen in the tissue sample, the enzyme or dye is activated, and the antigen can then be seen under a microscope. This type of test is used to check for a certain gene mutation, to help diagnose cancer, and to help tell one type of cancer from another type of cancer. This test may be used to look for changes in the INI1 gene.

Getting a second opinion

You may want to get a second opinion to confirm your child's diagnosis and treatment plan. If you seek a second opinion, you will need to get medical test results and reports from the first doctor to share with the second doctor. The second doctor will review the pathology report, slides, and scans before giving a recommendation. They may agree with the first doctor, suggest changes to the treatment plan, or provide more information about your child's cancer.

To learn more about choosing a doctor and getting a second opinion, visit

Prognostic factors for hepatoblastoma

If your child has been diagnosed with hepatoblastoma, you likely have questions about how serious the cancer is and your child's chances of survival. The likely outcome or course of a disease is called prognosis.

The prognosis for hepatoblastoma depends on:

- whether the cancer has spread throughout the liver

- the size of the tumor

- whether the type of hepatoblastoma is well-differentiated fetal (pure fetal) or small cell undifferentiated histology

- whether the cancer has spread to other places in the body, such as the diaphragm, lungs, or certain large blood vessels

- whether there is more than one tumor in the liver

- whether the outer covering around the tumor has broken open

- how the cancer responds to chemotherapy

- whether the cancer can be removed completely by surgery

- whether your child can have a liver transplant

- whether the AFP blood levels go down after treatment

- your child's age

- whether the cancer has just been diagnosed or has come back after treatment

For hepatoblastoma that comes back after initial treatment, the prognosis depends on:

- where in the body the tumor recurred

- the type of treatment used to treat the initial cancer

Hepatoblastoma may be cured if the tumor is small and can be completely removed by surgery.

No two people are alike, and responses to treatment can vary greatly. Your child's cancer care team is in the best position to talk with you about your child's prognosis.

Stages of hepatoblastoma

Cancer stage describes the extent of cancer in the body, especially whether the cancer has spread from where it first formed to other parts of the body.

In hepatoblastoma, the PRETEXT and POSTTEXT groups are used instead of stage to plan treatment. The results of the tests and procedures done to detect, diagnose, and find out whether the cancer has spread are used to determine the PRETEXT and POSTTEXT groups.

Two grouping systems are used for hepatoblastoma to decide whether the tumor can be removed by surgery:

- The PRETEXT group describes the tumor before the patient has any treatment.

- The POSTTEXT group describes the tumor after the patient has had treatment such as neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

The liver is divided into four sections for the two grouping systems. The PRETEXT and POSTTEXT groups depend on which sections of the liver have cancer. There are four PRETEXT and POSTTEXT groups.

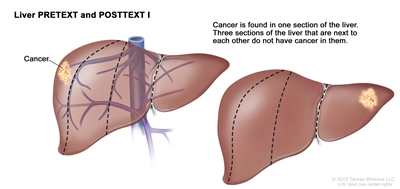

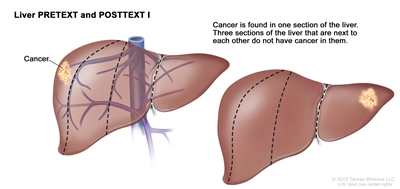

PRETEXT and POSTTEXT group I

Liver PRETEXT and POSTTEXT I. Cancer is found in one section of the liver. Three sections of the liver that are next to each other do not have cancer in them.

In group I, the cancer is found in one section of the liver. Three sections of the liver that are next to each other do not have cancer in them.

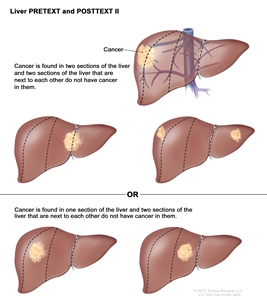

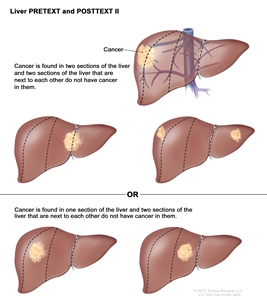

PRETEXT and POSTTEXT group II

Liver PRETEXT and POSTTEXT II. Cancer is found in one or two sections of the liver. Two sections of the liver that are next to each other do not have cancer in them.

In group II, cancer is found in one or two sections of the liver. Two sections of the liver that are next to each other do not have cancer in them.

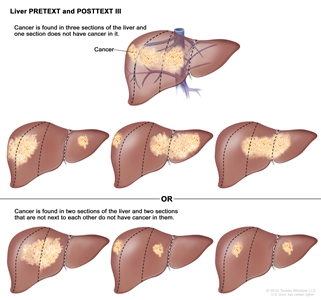

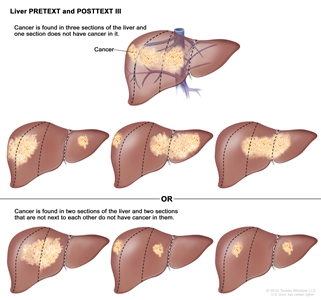

PRETEXT and POSTTEXT group III

Liver PRETEXT and POSTTEXT III. Cancer is found in three sections of the liver and one section does not have cancer in it, or cancer is found in two sections of the liver and two sections that are not next to each other do not have cancer in them.

In group III, one of the following is true:

- Cancer is found in three sections of the liver, and one section does not have cancer.

- Cancer is found in two sections of the liver, and two sections that are not next to each other do not have cancer in them.

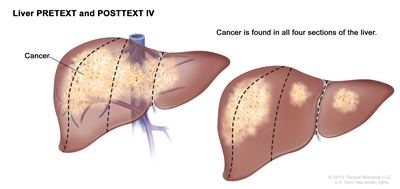

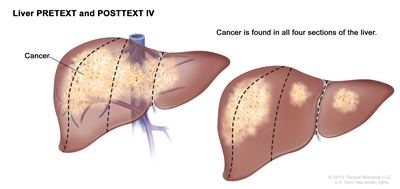

PRETEXT and POSTTEXT group IV

Liver PRETEXT and POSTTEXT IV. Cancer is found in all four sections of the liver.

In group IV, cancer is found in all four sections of the liver.

Progressive and recurrent hepatoblastoma

Hepatoblastoma can be a progressive or refractory disease. Progressive hepatoblastoma is cancer that continues to grow, spread, or worsen. Refractory hepatoblastoma is cancer that no longer responds to treatment.

Recurrent hepatoblastoma is cancer that has recurred (come back) after it has been treated. The cancer may come back in the liver or as metastatic tumors in other parts of the body. Tests will be done to help determine where the cancer has returned in the body, if it has spread, and how far. The type of treatment that your child will have for recurrent hepatoblastoma will depend on how far it has spread.

Learn more at

Types of treatment for hepatoblastoma

There are different types of treatment for children and adolescents with hepatoblastoma. You and your child's care team will work together to decide treatment. Many factors will be considered, such as your child's overall health and whether the cancer is newly diagnosed or has come back.

A pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer, oversees treatment of hepatoblastoma. The pediatric oncologist works with other health care providers who are experts in treating children with hepatoblastoma and who specialize in certain areas of medicine. It is especially important to have a pediatric surgeon with experience in liver surgery who can send patients to a liver transplant program if needed.

Other specialists may include:

- pediatrician

- radiation oncologist

- pathologist

- pediatric nurse specialist

- rehabilitation specialist

- psychologist

- social worker

- nutritionist

- child-life specialist

- fertility specialist

Your child's treatment plan will include information about the cancer, the goals of treatment, treatment options, and the possible side effects. It will be helpful to talk with your child's care team before treatment begins about what to expect. For help every step of the way, visit our booklet,

Surgery

When possible, the cancer is removed by surgery. The types of surgery that may be done are:

- Partial hepatectomy is surgery to remove the part of the liver where cancer is found. The part removed may be a wedge of tissue, an entire lobe, or a larger part of the liver, along with a small amount of normal tissue around it.

- Liver transplant is the removal of the entire liver by surgery, followed by a transplant of a healthy liver from a donor. A liver transplant may be possible when cancer has not spread beyond the liver, and a donated liver can be found. If the patient has to wait for a donated liver, other treatment is given as needed.

- Resection of metastases is surgery to remove cancer that has spread outside of the liver, such as to nearby tissues, the lungs, or the brain.

The type of surgery that can be done depends on:

- the PRETEXT group and POSTTEXT group

- the size of the primary tumor

- whether there is more than one tumor in the liver

- whether the cancer has spread to nearby large blood vessels

- the level of AFP in the blood

- whether the tumor can be shrunk by chemotherapy, so that it can be removed by surgery

- whether a liver transplant is needed

Chemotherapy is sometimes given before surgery to shrink the tumor and make it easier to remove. This is called neoadjuvant therapy.

After the doctor removes all the cancer that can be seen at the time of the surgery, some patients may be given chemotherapy or radiation therapy to kill any cancer cells that are left. Treatment given after the surgery to lower the risk that the cancer will come back is called adjuvant therapy.

Watchful waiting

Watchful waiting is closely monitoring a patient's condition without giving any treatment until signs or symptoms appear or change. In hepatoblastoma, this treatment is only used for small well-differentiated fetal (pure fetal) histology tumors that have been completely removed by surgery.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (also called chemo) uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells. Chemotherapy either kills the cancer cells or stops them from dividing. Chemotherapy may be given alone or with other types of treatment, such as radiation therapy.

There are two ways to give chemotherapy to treat hepatoblastoma:

- Systemic chemotherapy is chemotherapy that is injected into a vein. When given this way, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body.

- Regional chemotherapy is chemotherapy that is placed directly into the cerebrospinal fluid, an organ, or a body cavity such as the abdomen. When given this way, the drugs mainly affect cancer cells in those areas.

Chemoembolization of the hepatic artery (the main artery that supplies blood to the liver) is a type of regional chemotherapy used to treat hepatoblastoma that cannot be removed by surgery. The anticancer drug is injected into the hepatic artery through a catheter (thin tube). The drug is mixed with a substance that blocks the artery, cutting off blood flow to the tumor. Most of the anticancer drug is trapped near the tumor, and only a small amount of the drug reaches other parts of the body. The blockage may be temporary or permanent, depending on the substance used to block the artery. The tumor is prevented from getting the oxygen and nutrients it needs to grow. The liver continues to receive blood from the hepatic portal vein, which carries blood from the stomach and intestine to the liver. This procedure is also called transarterial chemoembolization, or TACE.

Chemotherapy drugs used alone or in combination to treat hepatoblastoma include:

- carboplatin

- cisplatin

- doxorubicin

- etoposide

- fluorouracil (5-FU)

- ifosfamide

- irinotecan

- vincristine

Other chemotherapy drugs not listed here may also be used.

Learn more about how chemotherapy works, how it is given, common side effects, and more at

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. The way the radiation therapy is given depends on the type of cancer being treated and the PRETEXT or POSTTEXT group.

Hepatoblastoma may be treated with external beam radiation therapy or internal radiation therapy:

- External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the area of the body with cancer. External radiation therapy is used to treat hepatoblastoma that cannot be removed by surgery or has spread to other parts of the body.

- Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer.

Radioembolization is a type of internal radiation therapy used to treat hepatoblastoma. A very small amount of a radioactive substance is attached to tiny beads that are injected into the hepatic artery (the main artery that supplies blood to the liver) through a thin tube called a catheter. The beads are mixed with a substance that blocks the artery, cutting off blood flow to the tumor. Most of the radiation is trapped near the tumor to kill the cancer cells. This is done to shrink the tumor or to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life for children with hepatoblastoma.

Learn more about radiation therapy and its side effects at

Radiofrequency ablation therapy

Radiofrequency ablation uses needles inserted directly through the skin or through an incision in the abdomen to reach the tumor. High-energy radio waves heat the needles and tumor, which kills cancer cells. Radiofrequency ablation is being used to treat recurrent hepatoblastoma.

Clinical trials

For some children, joining a clinical trial may be an option. There are different types of clinical trials for childhood cancer. For example, a treatment trial tests new treatments or new ways of using current treatments. Supportive care and palliative care trials look at ways to improve quality of life, especially for those who have side effects from cancer and its treatment.

You can use the

Learn more about clinical trials, including how to find and join one, at

Treatment of newly diagnosed hepatoblastoma

Treatment of newly diagnosed hepatoblastoma that can be removed by surgery at the time of diagnosis may include:

- surgery to remove the tumor, followed by combination chemotherapy, for hepatoblastoma that is mixed epithelial and fetal histology (not well-differentiated fetal histology) or aggressive chemotherapy for small cell undifferentiated histology

- surgery to remove the tumor, followed by watchful waiting or chemotherapy, for hepatoblastoma with well-differentiated fetal histology

Treatment of newly diagnosed hepatoblastoma that cannot be removed by surgery or is not removed at the time of diagnosis may include:

- combination chemotherapy to shrink the tumor, followed by surgery to remove the tumor

- combination chemotherapy, followed by a liver transplant

- chemoembolization or radioembolization of the hepatic artery to shrink the tumor, followed by surgery to remove the tumor

For newly diagnosed hepatoblastoma that has spread to other parts of the body at the time of diagnosis, combination chemotherapy is given to shrink the tumors in the liver and cancer that has spread to other parts of the body. After chemotherapy, imaging tests are done to check whether the tumors can be removed by surgery.

Treatment may include:

- if the tumors in the liver and other parts of the body (usually nodules in the lung) can be removed, surgery will be done to remove the tumors, followed by chemotherapy to kill any cancer cells that may remain

- if the tumor in other parts of the body cannot be removed, or a liver transplant is not possible, chemotherapy, chemoembolization or radioembolization of the hepatic artery, or radiation therapy may be given

- if the tumor in other parts of the body cannot be removed, or the patient does not want surgery, radiofrequency ablation may be given

Treatment of progressive or recurrent hepatoblastoma

Treatment of progressive or recurrent hepatoblastoma may include:

- surgery to remove isolated (single and separate) metastatic tumors with or without chemotherapy

- radiofrequency ablation

- combination chemotherapy

- liver transplant

Side effects and late effects of treatment

Cancer treatments can cause side effects. Which side effects your child might have depends on the type of treatment they receive, the dose, and how their body reacts. Talk with your child's treatment team about which side effects to look for and ways to manage them.

To learn more about side effects that begin during treatment for cancer, visit

Problems from cancer treatment that begin 6 months or later after treatment and continue for months or years are called late effects. Late effects of treatment may include:

- physical problems that affect liver function or hearing

- changes in mood, feelings, thinking, learning, or memory

- second cancers (new types of cancer)

Some late effects may be treated or controlled. It is important to talk with your child's doctors about the long-term effects cancer treatment can have on your child. Learn more about

Follow-up care

As your child goes through treatment, they will have follow-up tests or check-ups. Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the cancer or to find out the treatment group may be repeated to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Some of the tests will continue to be done from time to time after treatment has ended. The results of these tests can show if your child's condition has changed, or if the cancer has recurred (come back).

To learn more about follow-up tests, visit

Coping with your child's cancer

When a child has cancer, every member of the family needs support. Taking care of yourself during this difficult time is important. Reach out to your child's treatment team and to people in your family and community for support. To learn more, visit

Childhood Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Childhood hepatocellular carcinoma is a rare type of cancer that forms in liver cells called hepatocytes. Hepatocytes are the most common cells of the liver, and they carry out most of the functions of the liver.

The liver is one of the largest organs in the body. It has two lobes and fills the upper right side of the abdomen inside the rib cage. Three of the many important functions of the liver are:

- to make bile to help digest fats from food

- to store glycogen (sugar), which the body uses for energy

- to filter harmful substances from the blood so they can be passed from the body in stools and urine

Anatomy of the liver. The liver is in the upper abdomen near the stomach, intestines, gallbladder, and pancreas. The liver has a right lobe and a left lobe. Each lobe is divided into two sections (not shown).

Childhood hepatocellular carcinoma usually affects older children and adolescents. It is more common in areas of Asia that have higher rates of hepatitis B virus infection than in the United States.

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the most common type of liver cancer in adults. Risk factors, staging, and treatment for children are different than for adults. Learn more about hepatocellular carcinoma in adults at

Causes and risk factors for childhood hepatocellular carcinoma

Childhood hepatocellular carcinoma is caused by certain changes in the way liver cells function, especially how they grow and divide into new cells. Often, the exact cause of these cell changes is unknown. Learn more about how cancer develops at

A risk factor is anything that increases the chance of getting a disease. Not every child with one or more of these risk factors will develop hepatocellular carcinoma. And it will develop in some children who don't have a known risk factor.

The following syndromes or conditions are risk factors for childhood hepatocellular carcinoma:

- Alagille syndrome.

- Glycogen storage disease.

- Hepatitis B virus infection that was passed from mother to child at birth.

- Progressive familial intrahepatic disease.

- Tyrosinemia. Some patients with tyrosinemia are diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma after receiving a liver transplant, before there are signs or symptoms of cancer.

Hepatocellular carcinoma may develop in children with no underlying liver disease.

Talk with your child's doctor if you think your child may be at risk.

Symptoms of childhood hepatocellular carcinoma

Children may not have symptoms of hepatocellular carcinoma until the tumor has grown bigger. It's important to check with your child's doctor if your child has:

- a lump in the abdomen

- swelling in the abdomen

- abdominal pain

- weight loss for no known reason

- loss of appetite

- nausea and vomiting

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than hepatocellular carcinoma. The only way to know is to see your child's doctor.

Tests to diagnose childhood hepatocellular carcinoma

If your child has symptoms that suggest hepatocellular carcinoma, the doctor will need to find out if these are due to cancer or to another problem. The doctor will ask when the symptoms started and how often your child has been having them. They will also ask about your child's personal and family medical history and do a physical exam. Based on these results, the doctor may recommend other tests. If your child is diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma, the results of these tests will also help you and your child's doctor plan treatment.

The tests used to diagnose hepatocellular carcinoma in children may include:

Serum tumor marker test

Serum tumor marker tests measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by organs, tissues, or tumor cells in the body. Certain substances are linked to specific types of cancer when found in increased levels in the blood. These are called tumor markers. The blood of children who have liver cancer may have increased amounts of a hormone called beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) or a protein called alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). Other cancers, benign liver tumors, and certain noncancer conditions, including cirrhosis and hepatitis, can also increase AFP levels.

Complete blood count (CBC)

A CBC checks a sample of blood for:

- the number of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets

- the amount of hemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen) in the red blood cells

- the portion of the blood sample made up of red blood cells

Liver function tests

Liver function tests measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by the liver. A higher-than-normal amount of a substance can be a sign of liver damage or cancer.

Blood chemistry studies

Blood chemistry studies measure the amounts of certain substances, such as bilirubin or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), released into the blood by organs and tissues in the body. An unusual amount of a substance can be a sign of disease.

Hepatitis panel

A hepatitis panel checks for antigens or antibodies in the blood to see if there is or has been a hepatitis infection.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium

MRI uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the liver. A substance called gadolinium is injected into a vein. The gadolinium collects around the cancer cells, so they show up brighter in the picture. This procedure is also called nuclear MRI.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The child lies on a table that slides into the MRI machine, which takes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. The positioning of the child on the table depends on the part of the body being imaged.

CT scan (CAT scan)

A CT scan uses a computer linked to an x-ray machine to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, taken from different angles. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

A CT scan of the chest and abdomen is usually done to help diagnose childhood liver cancer.

Learn more about

Computed tomography (CT) scan. The child lies on a table that slides through the CT scanner, which takes a series of detailed x-ray pictures of areas inside the body.

Ultrasound exam

An ultrasound exam uses high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) that bounce off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. An ultrasound exam of the abdomen to check the large blood vessels is usually done to help diagnose childhood liver cancer.

Abdominal ultrasound. An ultrasound transducer connected to a computer is pressed against the skin of the abdomen. The transducer bounces sound waves off internal organs and tissues to make echoes that form a sonogram (computer picture).

Chest x-ray

An x-ray is a type of high-energy radiation that can go through the body onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body. A chest x-ray is one that makes pictures of the lungs.

Biopsy

Biopsy is a procedure in which a sample of tissue is removed from the tumor so that a pathologist can view it under a microscope to check for cancer. The doctor may remove as much tumor as safely possible during the same biopsy procedure.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry uses antibodies to check for certain antigens (markers) in a sample of a patient's tissue. The antibodies are usually linked to an enzyme or a fluorescent dye. After the antibodies bind to a specific antigen in the tissue sample, the enzyme or dye is activated, and the antigen can then be seen under a microscope. This type of test is used to help diagnose cancer and to help tell one type of cancer from another type.

Getting a second opinion

You may want to get a second opinion to confirm your child's diagnosis and treatment plan. If you seek a second opinion, you will need to get medical test results and reports from the first doctor to share with the second doctor. The second doctor will review the pathology report, slides, and scans before giving a recommendation. This doctor may agree with the first doctor, suggest changes to the treatment plan, or provide more information about your child's cancer.

To learn more about choosing a doctor and getting a second opinion, visit

Prognostic factors for childhood hepatocellular carcinoma

If your child has been diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma, you likely have questions about how serious the cancer is and your child's chances of survival. The likely outcome or course of a disease is called prognosis.

The prognosis for childhood hepatocellular carcinoma depends on:

- whether the cancer has spread throughout the liver

- whether the cancer can be removed completely by surgery

- whether the cancer has spread to other places in the body, such as the lungs

- how the cancer responds to chemotherapy

- whether your child has hepatitis B virus infection

- whether the cancer has just been diagnosed or has come back after treatment

For childhood hepatocellular carcinoma that recurs (comes back) after initial treatment, the prognosis depends on:

- where in the body the tumor recurred

- the type of treatment used to treat the initial cancer

No two people are alike, and responses to treatment can vary greatly. Your child's cancer care team is in the best position to talk with you about your child's prognosis.

Stages of childhood hepatocellular carcinoma

The cancer stage describes the extent of cancer in the body, especially whether the cancer has spread from where it first formed to other parts of the body.

In childhood hepatocellular carcinoma, the PRETEXT and POSTTEXT groups are used to plan treatment. The results of the tests and procedures done to detect, diagnose, and find out whether the cancer has spread are used to determine the PRETEXT and POSTTEXT groups.

Two grouping systems are used for childhood hepatocellular carcinoma to decide whether the tumor can be removed by surgery:

- The PRETEXT group describes the tumor before the patient has any treatment.

- The POSTTEXT group describes the tumor after the patient has had treatment such as neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

The liver is divided into four sections for the two grouping systems. The PRETEXT and POSTTEXT groups depend on which sections of the liver have cancer. There are four PRETEXT and POSTTEXT groups.

PRETEXT and POSTTEXT group I

Liver PRETEXT and POSTTEXT I. Cancer is found in one section of the liver. Three sections of the liver that are next to each other do not have cancer in them.

In group I, the cancer is found in one section of the liver. Three sections of the liver that are next to each other do not have cancer in them.

PRETEXT and POSTTEXT group II

Liver PRETEXT and POSTTEXT II. Cancer is found in one or two sections of the liver. Two sections of the liver that are next to each other do not have cancer in them.

In group II, cancer is found in one or two sections of the liver. Two sections of the liver that are next to each other do not have cancer in them.

PRETEXT and POSTTEXT group III

Liver PRETEXT and POSTTEXT III. Cancer is found in three sections of the liver and one section does not have cancer in it, or cancer is found in two sections of the liver and two sections that are not next to each other do not have cancer in them.

In group III, one of the following is true:

- Cancer is found in three sections of the liver, and one section does not have cancer.

- Cancer is found in two sections of the liver, and two sections that are not next to each other do not have cancer in them.

PRETEXT and POSTTEXT group IV

Liver PRETEXT and POSTTEXT IV. Cancer is found in all four sections of the liver.

In group IV, cancer is found in all four sections of the liver.

Progressive and recurrent childhood hepatocellular carcinoma

Childhood hepatocellular carcinoma can be a progressive disease or refractory disease. Progressive hepatocellular carcinoma is cancer that continues to grow, spread, or worsen. Refractory hepatocellular carcinoma is cancer that no longer responds to treatment.

Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma is cancer that has recurred (come back) after it has been treated. The cancer may come back in the liver or in other parts of the body. Tests will be done to help determine where the cancer has returned in the body, if it has spread, and how far. The type of treatment that your child will have for recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma will depend on how far it has spread.

Learn more at

Types of treatment for childhood hepatocellular carcinoma

There are different types of treatment for children and adolescents with hepatocellular carcinoma. You and your child's care team will work together to decide treatment. Many factors will be considered, such as your child's overall health and whether the cancer is newly diagnosed or has come back.

A pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer, will oversee treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. The pediatric oncologist works with other health care providers who are experts in treating children with hepatocellular carcinoma and who specialize in certain areas of medicine. It is especially important to have a pediatric surgeon with experience in liver surgery who can send patients to a liver transplant program if needed. Other specialists may include:

- pediatrician

- radiation oncologist

- pathologist

- pediatric nurse specialist

- rehabilitation specialist

- psychologist

- social worker

- nutritionist

- child-life specialist

- fertility specialist

Your child's treatment plan will include information about the cancer, the goals of treatment, treatment options, and the possible side effects. It will be helpful to talk with your child's care team before treatment begins about what to expect. For help every step of the way, visit our booklet,

Surgery

When possible, the cancer is removed by surgery. The types of surgery that may be done are:

- Partial hepatectomy is surgery to remove the part of the liver where cancer is found. The part removed may be a wedge of tissue, an entire lobe, or a larger part of the liver, along with a small amount of normal tissue around it.

- Liver transplant is the removal of the entire liver by surgery, followed by a transplant of a healthy liver from a donor. A liver transplant may be possible when cancer has not spread beyond the liver, and a donated liver can be found. If the patient has to wait for a donated liver, other treatment is given as needed.

- Resection of metastases is surgery to remove cancer that has spread outside of the liver, such as to nearby tissues, the lungs, or the brain.

The type of surgery that can be done depends on:

- the PRETEXT group and POSTTEXT group

- the size of the primary tumor

- whether there is more than one tumor in the liver

- whether the cancer has spread to nearby large blood vessels

- the level of AFP in the blood

- whether the tumor can be shrunk by chemotherapy so that it can be removed by surgery

- whether a liver transplant is needed

Chemotherapy is sometimes given before surgery to shrink the tumor and make it easier to remove. This is called neoadjuvant therapy.

After the doctor removes all the cancer that can be seen at the time of the surgery, some patients may be given chemotherapy or radiation therapy to kill any cancer cells that are left. Treatment given after the surgery to lower the risk that the cancer will come back is called adjuvant therapy.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (also called chemo) uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells. Chemotherapy either kills the cancer cells or stops them from dividing. Chemotherapy may be given alone or with other types of treatment, such as radiation therapy.

There are two main ways to give chemotherapy to treat childhood hepatocellular carcinoma:

- Systemic chemotherapy is chemotherapy that is injected into a vein or muscle. When given this way, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body.

- Regional chemotherapy is chemotherapy that is placed directly into the cerebrospinal fluid, an organ, or a body cavity such as the abdomen. When given this way, the drugs mainly affect cancer cells in those areas.

Chemoembolization of the hepatic artery (the main artery that supplies blood to the liver) is a type of regional chemotherapy used to treat childhood hepatocellular carcinoma that cannot be removed by surgery. The anticancer drug is injected into the hepatic artery through a catheter (thin tube). The drug is mixed with a substance that blocks the artery, cutting off blood flow to the tumor. Most of the anticancer drug is trapped near the tumor, and only a small amount of the drug reaches other parts of the body. The blockage may be temporary or permanent, depending on the substance used to block the artery. The tumor is prevented from getting the oxygen and nutrients it needs to grow. The liver continues to receive blood from the hepatic portal vein, which carries blood from the stomach and intestine to the liver. This procedure is also called transarterial chemoembolization, or TACE.

Chemotherapy drugs used alone or in combination to treat childhood hepatocellular carcinoma include:

- cisplatin

- doxorubicin

- fluorouracil (5-FU)

- vincristine

Other chemotherapy drugs not listed here may also be used.

Learn more about how chemotherapy works, how it is given, common side effects, and more at

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. Hepatocellular carcinoma in children may be treated with internal radiation therapy. Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer.

- Radioembolization is a type of internal radiation therapy used to treat childhood hepatocellular carcinoma. A very small amount of a radioactive substance is attached to tiny beads that are injected into the hepatic artery (the main artery that supplies blood to the liver) through a thin tube called a catheter. The beads are mixed with a substance that blocks the artery, cutting off blood flow to the tumor. Most of the radiation is trapped near the tumor to kill the cancer cells. This is done to shrink the tumor or to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life for children with hepatocellular carcinoma.

Learn more about radiation therapy and its side effects at

Antiviral treatment

Hepatocellular carcinoma that is linked to the hepatitis B virus may be treated with antiviral drugs.

Ablation therapy

Ablation therapy removes or destroys tissue. Radiofrequency ablation is a type of ablation therapy that may be used to treat hepatocellular carcinoma. During radiofrequency ablation, special needles are inserted directly through the skin or through an incision in the abdomen to reach the tumor. High-energy radio waves heat the needles and tumor which kills cancer cells.

Clinical trials

For some children, joining a clinical trial may be an option. There are different types of clinical trials for childhood cancer. For example, a treatment trial tests new treatments or new ways of using current treatments. Supportive care and palliative care trials look at ways to improve quality of life, especially for those who have side effects from cancer and its treatment.

You can use the

Learn more about clinical trials, including how to find and join one, at

Treatment of newly diagnosed childhood hepatocellular carcinoma

Treatment options for newly diagnosed hepatocellular carcinoma that can be removed by surgery at the time of diagnosis may include:

- surgery to remove the tumor, followed by chemotherapy

- combination chemotherapy, followed by surgery to remove the tumor

- surgery alone to remove the tumor

Treatment options for newly diagnosed hepatocellular carcinoma that cannot be removed by surgery and has not spread to other parts of the body at the time of diagnosis may include:

- chemotherapy to shrink the tumor, followed by surgery to completely remove the tumor

- chemotherapy to shrink the tumor

If surgery to completely remove the tumor is not possible, further treatment may include:

- liver transplant

- chemoembolization or radioembolization of the hepatic artery to shrink the tumor, followed by surgery to remove the tumor or liver transplant

- chemoembolization or radioembolization of the hepatic artery alone

- radioembolization of the hepatic artery as palliative therapy to relieve symptoms and improve the quality of life

Treatment for newly diagnosed hepatocellular carcinoma that has spread to other parts of the body at the time of diagnosis may include:

- Combination chemotherapy to shrink the tumor, followed by surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible from the liver and other places where cancer has spread. Studies have shown that this treatment may not work well, but some patients may benefit.

Treatment options for newly diagnosed hepatocellular carcinoma related to hepatitis B virus infection may include:

- surgery to remove the tumor, followed by antiviral drugs that treat infection caused by the hepatitis B virus

Treatment of progressive or recurrent childhood hepatocellular carcinoma

Treatment of progressive or recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma may include:

- chemoembolization of the hepatic artery to shrink the tumor before liver transplant

- radiofrequency ablation

- liver transplant

Side effects and late effects of treatment

Cancer treatments can cause side effects. Which side effects your child might have depends on the type of treatment they receive, the dose, and how their body reacts. Talk with your child's treatment team about which side effects to look for and ways to manage them.

For information about side effects that begin during treatment for cancer, visit

Problems from cancer treatment that begin 6 months or later after treatment and continue for months or years are called late effects. Late effects of cancer treatment may include:

- physical problems that affect liver function or hearing

- changes in mood, feelings, thinking, learning, or memory

- second cancers (new types of cancer)

Some late effects may be treated or controlled. It is important to talk with your child's doctors about the long-term effects cancer treatment can have on your child. Learn more about

Follow-up care

As your child goes through treatment, they will have follow-up tests or check-ups. Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the cancer or to find out the treatment group may be repeated to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Some of the tests will continue to be done from time to time after treatment has ended. The results of these tests can show if your child's condition has changed or if the cancer has recurred (come back). To learn more about follow-up tests, visit

Coping with your child's cancer

When your child has cancer, every member of the family needs support. Taking care of yourself during this difficult time is important. Reach out to your child's treatment team and to people in your family and community for support. To learn more, visit

Childhood Undifferentiated Embryonal Sarcoma of the Liver

Childhood undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver is a rare cancer that usually forms in the tissues of the right lobe of the liver. This type of liver cancer usually occurs in children between 5 and 10 years but can also occur in adolescence. It often spreads throughout the liver and/or to the lungs.

The liver is one of the largest organs in the body. It has two lobes and fills the upper right side of the abdomen inside the rib cage. Three of the many important functions of the liver include:

- to make bile to help digest fats from food

- to store glycogen (sugar), which the body uses for energy

- to filter harmful substances from the blood so they can be passed from the body in stools and urine

Anatomy of the liver. The liver is in the upper abdomen near the stomach, intestines, gallbladder, and pancreas. The liver has a right lobe and a left lobe. Each lobe is divided into two sections (not shown).

Symptoms of childhood undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver

Children may not have symptoms of undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver until the tumor has grown bigger. It's important to check with your child's doctor if your child has:

- a lump in the abdomen

- abdominal pain

- weight loss for no known reason

- loss of appetite

- fatigue or loss of energy

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver. The only way to know is to see your child's doctor.

Tests to diagnose childhood undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver

If your child has symptoms that suggest undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver, the doctor will need to find out if these are due to cancer or another problem. The doctor will ask when the symptoms started and how often your child has been having them. They will also ask about your child's personal and family medical history and do a physical exam. Based on these results, the doctor may recommend other tests. If your child is diagnosed with liver cancer, the results of these tests will help you and your child's doctor plan treatment.

The tests used to diagnose undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver may include:

Complete blood count (CBC)

A CBC checks a sample of blood for:

- the number of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets

- the amount of hemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen) in the red blood cells

- the portion of the blood sample made up of red blood cells

Liver function tests

Liver function tests measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by the liver. A higher-than-normal amount of a substance can be a sign of liver damage or cancer.

Blood chemistry studies

Blood chemistry studies measure the amounts of certain substances, such as bilirubin or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), released into the blood by organs and tissues in the body. An unusual amount of a substance can be a sign of disease.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium

MRI uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to take a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the liver. A substance called gadolinium is injected into a vein. The gadolinium collects around the cancer cells so they show up brighter in the picture. The procedure is also called nuclear MRI.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The child lies on a table that slides into the MRI machine, which takes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. The positioning of the child on the table depends on the part of the body being imaged.

CT scan (CAT scan)

A CT scan uses a computer linked to an x-ray machine to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, taken from different angles. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

A CT scan of the chest and abdomen is usually done to help diagnose childhood liver cancer.

Learn more about

Computed tomography (CT) scan. The child lies on a table that slides through the CT scanner, which takes a series of detailed x-ray pictures of areas inside the body.

Ultrasound exam

An ultrasound exam uses high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) that bounce off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. An ultrasound exam of the abdomen to check the large blood vessels is usually done to help diagnose childhood liver cancer.

Abdominal ultrasound. An ultrasound transducer connected to a computer is pressed against the skin of the abdomen. The transducer bounces sound waves off internal organs and tissues to make echoes that form a sonogram (computer picture).

Chest x-ray

An x-ray is a type of high-energy radiation that can go through the body onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body. A chest x-ray is one that makes pictures of the lungs.

Biopsy

Biopsy is a procedure in which a sample of tissue is removed from the tumor so that a pathologist can view it under a microscope to check for cancer. The doctor may remove as much tumor as safely possible during the same biopsy procedure.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry uses antibodies to check for certain antigens (markers) in a sample of a patient's tissue. The antibodies are usually linked to an enzyme or a fluorescent dye. After the antibodies bind to a specific antigen in the tissue sample, the enzyme or dye is activated, and the antigen can then be seen under a microscope. This type of test is used to help diagnose cancer and to help tell one type of cancer from another type.

Getting a second opinion

You may want to get a second opinion to confirm your child's diagnosis and treatment plan. If you seek a second opinion, you will need to get medical test results and reports from the first doctor to share with the second doctor. The second doctor will review the pathology report, slides, and scans. This doctor may agree with the first doctor, suggest changes to the treatment plan, or provide more information about your child's cancer.

To learn more about choosing a doctor and getting a second opinion, visit

Prognostic factors for childhood undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver

If your child has been diagnosed with undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver, you likely have questions about how serious the cancer is and your child's chances of survival. The likely outcome or course of a disease is called prognosis.

The prognosis for undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver depends on:

- the size of the tumor

- how the cancer responds to chemotherapy

- whether the cancer can be removed completely by surgery

- whether your child can have a liver transplant

- whether the cancer has spread to other places in the body, such as the lungs

- whether the cancer has just been diagnosed or has come back after treatment

For childhood undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver that comes back after initial treatment, the prognosis depends on:

- where in the body the tumor came back

- the type of treatment used to treat the initial cancer

No two people are alike, and responses to treatment can vary greatly. Your child's cancer care team is in the best position to talk with you about your child's prognosis.

Types of treatment for childhood undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver

There are different types of treatment for children and adolescents with undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver. You and your child's care team will work together to decide treatment. Many factors will be considered, such as your child's overall health and whether the cancer is newly diagnosed or has come back.

A pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer, will oversee treatment of undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver. The pediatric oncologist works with other health care providers who are experts in treating children with undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver and who specialize in certain areas of medicine. It is especially important to have a pediatric surgeon with experience in liver surgery who can send patients to a liver transplant program if needed. Other specialists may include:

- pediatrician

- radiation oncologist

- pathologist

- pediatric nurse specialist

- rehabilitation specialist

- psychologist

- social worker

- nutritionist

- child-life specialist

Your child's treatment plan will include information about the cancer, the goals of treatment, treatment options, and the possible side effects. It will be helpful to talk with your child's care team before treatment begins about what to expect. For help every step of the way, visit our booklet,

Surgery

When possible, the cancer is removed by surgery. The following types of surgery may be done:

- Partial hepatectomy is surgery to remove the part of the liver where cancer is found. The part removed may be a wedge of tissue, an entire lobe, or a larger part of the liver, along with some of the healthy tissue around it. The remaining liver tissue takes over the functions of the liver and may regrow.

- Liver transplant is the removal of the entire liver by surgery, followed by a transplant of a healthy liver from a donor. A liver transplant may be done when the cancer is in the liver only, and a donated liver can be found. If the patient has to wait for a donated liver, other treatment is given as needed.

Chemotherapy is sometimes given before surgery to shrink the tumor and make it easier to remove. This is called neoadjuvant therapy.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (also called chemo) uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells. Chemotherapy either kills the cancer cells or stops them from dividing.

For childhood undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver, the chemotherapy is injected into a vein. When given this way, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body.

Chemotherapy drugs used alone or in combination to treat undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver in children include:

- cisplatin

- cyclophosphamide

- dactinomycin

- doxorubicin

- etoposide

- ifosfamide

- vincristine

Other chemotherapy drugs not listed here may also be used.

Learn more about how chemotherapy works, how it is given, common side effects, and more at

Clinical trials

For some children, joining a clinical trial may be an option. There are different types of clinical trials for childhood cancer. For example, a treatment trial tests new treatments or new ways of using current treatments. Supportive care and palliative care trials look at ways to improve quality of life, especially for those who have side effects from cancer and its treatment.

You can use the

Learn more about clinical trials, including how to find and join one, at

Treatment of childhood undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver

Treatment of newly diagnosed childhood undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver may include:

- surgery to remove the tumor

- chemotherapy before surgery, after surgery, or both

- liver transplant if surgery to remove the tumor is not possible

If the first surgery is unable to remove the entire tumor, a second surgery may be done to remove the remaining tumor cells.

Sometimes childhood undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver continues to grow or recurs (comes back) after treatment. The cancer may come back in the liver or in other parts of the body. Your child's doctor will work with you to plan treatment if your child is diagnosed with recurrent undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver.

Side effects and late effects of treatment

Cancer treatments can cause side effects. Which side effects your child might have depends on the type of treatment they receive, the dose, and how their body reacts. Talk with your child's treatment team about which side effects to look for and ways to manage them.

To learn more about side effects that begin during treatment, visit

Problems from cancer treatment that begin 6 months or later after treatment and continue for months or years are called late effects. Late effects of cancer treatment may include:

- physical problems

- changes in mood, feelings, thinking, learning, or memory

- second cancers (new types of cancer)

Some late effects may be treated or controlled. It is important to talk with your child's doctors about the long-term effects cancer treatment can have on your child. Learn more about

Follow-up care

As your child goes through treatment, they will have follow-up tests or check-ups. Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the cancer or to find out the treatment group may be repeated to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Some of the tests will continue to be done from time to time after treatment has ended. The results of these tests can show if your child's condition has changed or if the cancer has come back. To learn more about follow-up tests, visit

Coping with your child's cancer

When your child has cancer, every member of the family needs support. Taking care of yourself during this difficult time is important. Reach out to your child's treatment team and to people in your family and community for support. To learn more, visit

Infantile Choriocarcinoma of the Liver

Infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver is a very rare type of cancer that starts in the placenta and spreads to the fetus. The tumor is usually found during the first few months after the baby is born.

The liver is one of the largest organs in the body. It has two lobes and fills the upper right side of the abdomen inside the rib cage. Three of the many important functions of the liver are:

- to make bile to help digest fats from food

- to store glycogen (sugar), which the body uses for energy

- to filter harmful substances from the blood so they can be passed from the body in stools and urine

Anatomy of the liver. The liver is in the upper abdomen near the stomach, intestines, gallbladder, and pancreas. The liver has a right lobe and a left lobe. Each lobe is divided into two sections (not shown).

The mother of the child may also be diagnosed with choriocarcinoma. For more information on the treatment of choriocarcinoma in the mother, visit

Symptoms of infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver

Children may not have symptoms of infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver until the tumor has grown bigger. It's important to check with your child's doctor if your child has:

- a lump in the abdomen

- swelling in the abdomen

- hemorrhage

- weakness or increased sleeping

- paleness (loss of normal color from the skin or inside of the nose and mouth)

- shortness of breath

- signs of puberty

- slow growth, poor eating, or is not meeting developmental milestones

These symptoms may be caused by problems other than infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver. The only way to know is to see your child's doctor.

Tests to diagnose infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver

If your child has symptoms that suggest infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver, the doctor will need to find out if these are due to cancer or another problem. The doctor will ask when the symptoms started and how often your child has been having them. They will also ask about your child's personal and family medical history and do a physical exam. Based on these results, the doctor may recommend other tests. If your child is diagnosed with liver cancer, the results of these tests will help you and your child's doctor plan treatment.

The tests used to diagnose infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver may include:

Serum tumor marker test

Serum tumor marker tests measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by organs, tissues, or tumor cells in the body. Certain substances are linked to specific types of cancer when found in increased levels in the blood. These are called tumor markers. The blood of children who have liver cancer may have increased amounts of a hormone called beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (beta-hCG) or a protein called alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). Other cancers, benign liver tumors, and certain noncancer conditions, including cirrhosis and hepatitis, can also increase AFP levels.

Complete blood count (CBC)

A CBC checks a sample of blood for:

- the number of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets

- the amount of hemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen) in the red blood cells

- the portion of the blood sample made up of red blood cells

Liver function tests

Liver function tests measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by the liver. A higher-than-normal amount of a substance can be a sign of liver damage or cancer.

Blood chemistry studies

Blood chemistry studies measure the amounts of certain substances, such as bilirubin or lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), released into the blood by organs and tissues in the body. An unusual amount of a substance can be a sign of disease.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium

MRI uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the liver. A substance called gadolinium is injected into a vein. The gadolinium collects around the cancer cells so they show up brighter in the picture. This procedure is also called nuclear MRI.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The child lies on a table that slides into the MRI machine, which takes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. The positioning of the child on the table depends on the part of the body being imaged.

CT scan (CAT scan)

A CT scan uses a computer linked to an x-ray machine to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, taken from different angles. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

A CT scan of the chest and abdomen is usually done to help diagnose childhood liver cancer.

Learn more about

Computed tomography (CT) scan. The child lies on a table that slides through the CT scanner, which takes a series of detailed x-ray pictures of areas inside the body.

Ultrasound exam

An ultrasound exam uses high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) that bounce off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. An ultrasound exam of the abdomen to check the large blood vessels is usually done to help diagnose childhood liver cancer.

Abdominal ultrasound. An ultrasound transducer connected to a computer is pressed against the skin of the abdomen. The transducer bounces sound waves off internal organs and tissues to make echoes that form a sonogram (computer picture).

Chest x-ray

An x-ray is a type of high-energy radiation that can go through the body onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body. A chest x-ray is one that makes pictures of the lungs.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry uses antibodies to check for certain antigens (markers) in a sample of a patient's tissue. The antibodies are usually linked to an enzyme or a fluorescent dye. After the antibodies bind to a specific antigen in the tissue sample, the enzyme or dye is activated, and the antigen can then be seen under a microscope. This type of test is used to help diagnose cancer and to help tell one type of cancer from another type.

Getting a second opinion

You may want to get a second opinion to confirm your child's diagnosis and treatment plan. If you seek a second opinion, you will need to get medical test results and reports from the first doctor to share with the second doctor. The second doctor will review the pathology report, slides, and scans before giving a recommendation. This doctor may agree with the first doctor, suggest changes to the treatment plan, or provide more information about your child's cancer.

To learn more about choosing a doctor and getting a second opinion, visit

Prognostic factors for infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver

If your child has been diagnosed with infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver, you likely have questions about how serious the cancer is and your child's chances of survival. The likely outcome or course of a disease is called prognosis.

The prognosis for infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver depends on:

- the size of the tumor

- your child's health

- how the cancer responds to chemotherapy

- whether the cancer can be removed completely by surgery

- whether your child can have a liver transplant

- whether the cancer has just been diagnosed or has come back

For infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver that comes back after initial treatment, the prognosis depends on:

- where in the body the tumor recurred

- the type of treatment used to treat the initial cancer

No two people are alike, and responses to treatment can vary greatly. Your child's cancer care team is in the best position to talk with you about your child's prognosis.

Types of treatment for infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver

There are different types of treatment for children with infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver. You and your child's care team will work together to decide treatment. Many factors will be considered, such as your child's overall health and whether the cancer is newly diagnosed or has come back.

A pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer, will oversee treatment of infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver. The pediatric oncologist works with other health care providers who are experts in treating children with infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver and who specialize in certain areas of medicine. It is especially important to have a pediatric surgeon with experience in liver surgery who can send patients to a liver transplant program if needed. Other specialists may include:

- pediatrician

- radiation oncologist

- pathologist

- pediatric nurse specialist

- rehabilitation specialist

- psychologist

- social worker

- nutritionist

- child-life specialist

Your child's treatment plan will include information about the cancer, the goals of treatment, treatment options, and the possible side effects. It will be helpful to talk with your child's care team before treatment begins about what to expect. For help every step of the way, visit our booklet,

Surgery

When possible, the cancer is removed by surgery. The types of surgery that may be done are:

- Partial hepatectomy is surgery to remove the part of the liver where cancer is found. The part removed may be a wedge of tissue, an entire lobe, or a larger part of the liver, along with some of the healthy tissue around it. The remaining liver tissue takes over the functions of the liver and may regrow.

- Liver transplant is the removal of the entire liver by surgery, followed by a transplant of a healthy liver from a donor. A liver transplant may be done when the cancer is in the liver only, and a donated liver can be found. If the patient has to wait for a donated liver, other treatment is given as needed.

Chemotherapy is sometimes given before surgery to shrink the tumor and make it easier to remove. This is called neoadjuvant therapy.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (also called chemo) uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells. Chemotherapy either kills the cancer cells or stops them from dividing. Chemotherapy may be given alone or with other types of treatment.

For infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver, the chemotherapy is injected into a vein. When given this way, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body.

Chemotherapy drugs used alone or in combination to treat infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver include:

- bleomycin

- cisplatin

- etoposide

- methotrexate

Other chemotherapy drugs not listed here may also be used.

Learn more about how chemotherapy works, how it is given, common side effects, and more at

Clinical trials

For some children, joining a clinical trial may be an option. There are different types of clinical trials for childhood cancer. For example, a treatment trial tests new treatments or new ways of using current treatments. Supportive care and palliative care trials look at ways to improve quality of life, especially for those who have side effects from cancer and its treatment.

You can use the

Learn more about clinical trials, including how to find and join one, at

Treatment of infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver

Treatment of newly diagnosed infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver may include:

- chemotherapy to help shrink the tumor, followed by surgery to remove the tumor

- surgery to remove the tumor, followed by chemotherapy

- chemotherapy, followed by liver transplant if surgery to remove the tumor is not possible

Sometimes infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver continues to grow or recurs (comes back) after treatment. The cancer may come back in the liver or in other parts of the body. Your child's doctor will work with you to plan treatment if your child is diagnosed with recurrent infantile choriocarcinoma of the liver.

Side effects and late effects of treatment

Cancer treatments can cause side effects. Which side effects your child might have depends on the type of treatment they receive, the dose, and how their body reacts. Talk with your child's treatment team about which side effects to look for and ways to manage them.

To learn more about side effects that begin during treatment for cancer, visit

Problems from cancer treatment that begin 6 months or later after treatment and continue for months or years are called late effects. Late effects of cancer treatment may include:

- physical problems that affect hearing

- changes in mood, feelings, thinking, learning, or memory

- second cancers (new types of cancer)

Some late effects may be treated or controlled. It is important to talk with your child's doctors about the long-term effects cancer treatment can have on your child. Learn more about

Follow-up care

As your child goes through treatment, they will have follow-up tests or check-ups. Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the cancer or to find out the treatment group may be repeated to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Some of the tests will continue to be done from time to time after treatment has ended. The results of these tests can show if your child's condition has changed or if the cancer has come back. To learn more about follow-up tests, visit

Coping with your child's cancer

When your child has cancer, every member of the family needs support. Taking care of yourself during this difficult time is important. Reach out to your child's treatment team and to people in your family and community for support. To learn more, visit

Last Revised: 2025-02-21

If you want to know more about cancer and how it is treated, or if you wish to know about clinical trials for your type of cancer, you can call the NCI's Cancer Information Service at 1-800-422-6237, toll free. A trained information specialist can talk with you and answer your questions.

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the

Healthwise, Healthwise for every health decision, and the Healthwise logo are trademarks of Ignite Healthwise, LLC.

Page Footer

I want to...

Audiences

Secure Member Sites

The Cigna Group Information

Disclaimer

Individual and family medical and dental insurance plans are insured by Cigna Health and Life Insurance Company (CHLIC), Cigna HealthCare of Arizona, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Illinois, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Georgia, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of North Carolina, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of South Carolina, Inc., and Cigna HealthCare of Texas, Inc. Group health insurance and health benefit plans are insured or administered by CHLIC, Connecticut General Life Insurance Company (CGLIC), or their affiliates (see