Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage

Plans through your employer

Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

Learn

Living or working abroad?

Childhood Melanoma Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

Incidence

Melanoma is rare in children. However, it is the most common skin cancer in children, followed by basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas.[

Approximately 300 cases of melanoma are diagnosed each year in patients younger than 20 years in the United States, accounting for 0.3% of all new cases of melanoma.[

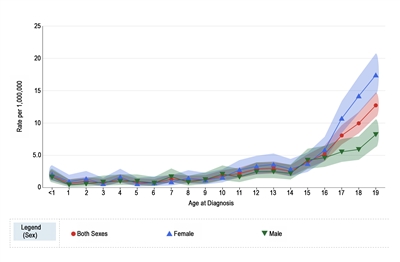

Melanoma annual incidence in the United States increases with age, as shown in

Figure 1. Melanoma incidence rates by age at diagnosis from 2016 to 2020. Reprinted with permission from the National Childhood Cancer Registry. NCCR*Explorer: An interactive website for NCCR cancer statistics [Internet]. National Cancer Institute; 2023 Sep 7. [updated: 2023 Sep 8; cited 2023 Dec 15]. Available from: https://nccrexplorer.ccdi.cancer.gov.

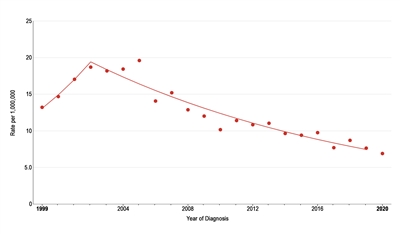

The incidence of pediatric melanoma (aged 0–19 years) increased by an average of 1.6% per year between 1975 and 1996. As shown in

Figure 2. Trends in melanoma age-adjusted incidence rates from 1999 to 2020 for adolescents aged 15 to 19 years. Reprinted with permission from the National Childhood Cancer Registry. NCCR*Explorer: An interactive website for NCCR cancer statistics [Internet]. National Cancer Institute; 2023 Sep 7. [updated: 2023 Sep 8; cited 2023 Dec 15]. Available from: https://nccrexplorer.ccdi.cancer.gov.

A retrospective study of 22,524 skin pathology reports from patients younger than 20 years identified 38 melanomas, 33 of which occurred in patients aged 15 to 19 years. Investigators reported that the number of lesions that needed to be excised to identify one melanoma was 479.8, which is 20 times higher than in the adult population.[

References:

- Sasson M, Mallory SB: Malignant primary skin tumors in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 8 (4): 372-7, 1996.

- Fishman C, Mihm MC, Sober AJ: Diagnosis and management of nevi and cutaneous melanoma in infants and children. Clin Dermatol 20 (1): 44-50, 2002 Jan-Feb.

- Hamre MR, Chuba P, Bakhshi S, et al.: Cutaneous melanoma in childhood and adolescence. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 19 (5): 309-17, 2002 Jul-Aug.

- Ceballos PI, Ruiz-Maldonado R, Mihm MC: Melanoma in children. N Engl J Med 332 (10): 656-62, 1995.

- Schmid-Wendtner MH, Berking C, Baumert J, et al.: Cutaneous melanoma in childhood and adolescence: an analysis of 36 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 46 (6): 874-9, 2002.

- Pappo AS: Melanoma in children and adolescents. Eur J Cancer 39 (18): 2651-61, 2003.

- Huynh PM, Grant-Kels JM, Grin CM: Childhood melanoma: update and treatment. Int J Dermatol 44 (9): 715-23, 2005.

- Christenson LJ, Borrowman TA, Vachon CM, et al.: Incidence of basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas in a population younger than 40 years. JAMA 294 (6): 681-90, 2005.

- National Cancer Institute: SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Melanoma of the Skin. Bethesda, Md: National Cancer Institute.

Available online . Last accessed December 15, 2023. - National Cancer Institute: NCCR*Explorer: An interactive website for NCCR cancer statistics. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Available online . Last accessed February 25, 2025. - Paulson KG, Gupta D, Kim TS, et al.: Age-Specific Incidence of Melanoma in the United States. JAMA Dermatol 156 (1): 57-64, 2020.

- Moscarella E, Zalaudek I, Cerroni L, et al.: Excised melanocytic lesions in children and adolescents - a 10-year survey. Br J Dermatol 167 (2): 368-73, 2012.

Risk Factors

Conditions associated with an increased risk of developing melanoma in children and adolescents include the following:

- Giant melanocytic nevi.[

1 ] - Xeroderma pigmentosum. This is a rare recessive disorder characterized by extreme sensitivity to sunlight, keratosis, and various neurological manifestations.[

1 ] For more information about xeroderma pigmentosum, seeGenetics of Skin Cancer . - Immunodeficiency or immunosuppression.[

2 ] - Hereditary retinoblastoma.[

3 ] - Werner syndrome.[

4 ,5 ] - Neurocutaneous melanosis. This is an unusual condition that arises in the context of congenital melanocytic nevi and is associated with large or multiple congenital nevi of the skin in association with meningeal melanosis or melanoma. Approximately 2.5% of patients with large congenital nevi develop this condition, and those with increased numbers of satellite nevi are at greatest risk.[

6 ,7 ]Patients with central nervous system (CNS) melanomas arising in the context of congenital melanocytic nevi syndrome have a poor prognosis, with a mortality rate of 100%. Most of these patients have NRAS variants. Therefore, mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway inhibitors might be used in the treatment of this disease. Four children who received a MEK inhibitor experienced transient symptomatic improvements. However, all patients eventually died of disease progression.[

8 ] A German registry identified five children with CNS melanomas who had neurocutaneous melanocytosis.[9 ] All patients died 0.3 to 0.8 years after they were diagnosed. - Family history of melanoma.

Phenotypic traits associated with an increased risk of melanoma in adults have been documented in children and adolescents with melanoma and include the following:[

- Exposure to UV sunlight. Increased exposure to ambient UV radiation increases disease risk.

- Red hair.

- Blue eyes.

- Poor tanning ability.

- Freckling.

- Dysplastic nevi.

- Increased number of melanocytic nevi.

Germline pathogenic variants associated with an increased risk of melanoma in children include the following:

- MC1R gene. A multinational consortium performed a retrospective review of germline pathogenic variants in the MC1R gene.[

17 ] The investigators analyzed data from 233 young patients (aged ≤20 years), 932 adult patients (aged ≥35 years), and 932 healthy adult controls. MC1R variants were more prevalent in childhood and adolescent patients with melanoma than in adult patients with melanoma. This finding was especially true for patients aged 18 years or younger. - CDKN2A gene (p16 gene). Familial melanoma comprises 8% to 12% of melanoma cases. p16 germline pathogenic variants have been described in up to 7% of families with two first-degree relatives with melanoma and in up to 80% of families having one member with multiple primary melanomas.[

18 ] In a prospective study of 60 families who had more than three members with melanoma,[19 ] one-half of the 60 families studied had a germline CDKN2A pathogenic variant. Regardless of CDKN2A status, melanoma-prone families were found to have sixfold to 28-fold higher percentages of members with pediatric melanoma compared with the general population of patients with melanoma in the United States. Within CDKN2A-positive families, pediatric patients with melanoma were significantly more likely to have multiple melanomas compared with their relatives who were older than 20 years at diagnosis (71% vs. 38%, respectively; P = .004). CDKN2A-positive families had significantly higher percentages of pediatric patients with melanoma compared with CDKN2A-negative families (11.1% vs. 2.5%, respectively; P = .004). - MITF p.E318K variant. In one series of patients younger than 21 years, 3 of 123 patients (2.4%) had an MITF substitution considered to confer a moderate risk of developing cutaneous melanoma.[

20 ,21 ]

References:

- Ceballos PI, Ruiz-Maldonado R, Mihm MC: Melanoma in children. N Engl J Med 332 (10): 656-62, 1995.

- Pappo AS: Melanoma in children and adolescents. Eur J Cancer 39 (18): 2651-61, 2003.

- Kleinerman RA, Tucker MA, Tarone RE, et al.: Risk of new cancers after radiotherapy in long-term survivors of retinoblastoma: an extended follow-up. J Clin Oncol 23 (10): 2272-9, 2005.

- Shibuya H, Kato A, Kai N, et al.: A case of Werner syndrome with three primary lesions of malignant melanoma. J Dermatol 32 (9): 737-44, 2005.

- Kleinerman RA, Yu CL, Little MP, et al.: Variation of second cancer risk by family history of retinoblastoma among long-term survivors. J Clin Oncol 30 (9): 950-7, 2012.

- Hale EK, Stein J, Ben-Porat L, et al.: Association of melanoma and neurocutaneous melanocytosis with large congenital melanocytic naevi--results from the NYU-LCMN registry. Br J Dermatol 152 (3): 512-7, 2005.

- Makkar HS, Frieden IJ: Neurocutaneous melanosis. Semin Cutan Med Surg 23 (2): 138-44, 2004.

- Kinsler VA, O'Hare P, Jacques T, et al.: MEK inhibition appears to improve symptom control in primary NRAS-driven CNS melanoma in children. Br J Cancer 116 (8): 990-993, 2017.

- Abele M, Forchhammer S, Eigentler TK, et al.: Melanoma of the central nervous system based on neurocutaneous melanocytosis in childhood: A rare but fatal condition. Pediatr Blood Cancer 71 (4): e30859, 2024.

- Heffernan AE, O'Sullivan A: Pediatric sun exposure. Nurse Pract 23 (7): 67-8, 71-8, 83-6, 1998.

- Berg P, Lindelöf B: Differences in malignant melanoma between children and adolescents. A 35-year epidemiological study. Arch Dermatol 133 (3): 295-7, 1997.

- Elwood JM, Jopson J: Melanoma and sun exposure: an overview of published studies. Int J Cancer 73 (2): 198-203, 1997.

- Strouse JJ, Fears TR, Tucker MA, et al.: Pediatric melanoma: risk factor and survival analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology and end results database. J Clin Oncol 23 (21): 4735-41, 2005.

- Whiteman DC, Valery P, McWhirter W, et al.: Risk factors for childhood melanoma in Queensland, Australia. Int J Cancer 70 (1): 26-31, 1997.

- Tucker MA, Fraser MC, Goldstein AM, et al.: A natural history of melanomas and dysplastic nevi: an atlas of lesions in melanoma-prone families. Cancer 94 (12): 3192-209, 2002.

- Ducharme EE, Silverberg NB: Pediatric malignant melanoma: an update on epidemiology, detection, and prevention. Cutis 84 (4): 192-8, 2009.

- Pellegrini C, Botta F, Massi D, et al.: MC1R variants in childhood and adolescent melanoma: a retrospective pooled analysis of a multicentre cohort. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 3 (5): 332-342, 2019.

- Soufir N, Avril MF, Chompret A, et al.: Prevalence of p16 and CDK4 germline mutations in 48 melanoma-prone families in France. The French Familial Melanoma Study Group. Hum Mol Genet 7 (2): 209-16, 1998.

- Goldstein AM, Stidd KC, Yang XR, et al.: Pediatric melanoma in melanoma-prone families. Cancer 124 (18): 3715-3723, 2018.

- Pellegrini C, Raimondi S, Di Nardo L, et al.: Melanoma in children and adolescents: analysis of susceptibility genes in 123 Italian patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 36 (2): 213-221, 2022.

- Guhan SM, Artomov M, McCormick S, et al.: Cancer risks associated with the germline MITF(E318K) variant. Sci Rep 10 (1): 17051, 2020.

Diagnostic Evaluation

The diagnosis of pediatric melanomas may be difficult, and many of these lesions may be confused with so-called melanocytic lesions with unknown malignant potential.[

The diagnostic evaluation of pediatric melanomas includes the following:

- Biopsy or excision. Biopsy or excision is necessary to diagnose any skin cancer and determine additional treatment. Although basal cell carcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas are generally curable with surgery alone, melanoma requires greater consideration because of its potential for metastasis. The width of surgical margins in melanoma is dictated by the site, size, and thickness of the lesion and ranges from 0.5 cm for in situ lesions to 2 cm or more for thicker lesions.[

4 ] To achieve negative margins in children, wide excision with skin grafting may become necessary in selected cases. Partial shave biopsy may compromise microstaging and is associated with more invasive, definitive surgical treatments.[5 ] - Lymph node evaluation. Examination of regional lymph nodes using sentinel lymph node biopsy has become routine in many centers.[

6 ,7 ] Sentinel lymph node biopsy is recommended for patients with lesions measuring 0.8 cm or larger,[4 ] as well as for patients whose lesions are less than 0.8 cm and who have ulceration or other unfavorable features such as lymphovascular invasion, high mitotic rate, young age, or a positive margin biopsy.[4 ,6 ,8 ,9 ,10 ]The indications for this procedure in patients with spitzoid melanomas have not been clearly defined. In a systematic review of 541 patients with atypical Spitz tumors, 303 (56%) underwent sentinel lymph node biopsy and 119 (39%) had a positive sentinel node. Further lymph node dissection in 97 of these patients revealed additional positive nodes in 18 patients (19%).[

11 ] Despite the high incidence of nodal metastases, only six patients developed disseminated disease. This finding challenges the prognostic and therapeutic benefit of this procedure in children with these lesions. In the future, molecular markers, such as the presence of TERT promoter variants, may help identify which patients might benefit from this procedure.[12 ]The role of complete lymph node dissection after a positive sentinel node and the value of adjuvant therapies in these patients is discussed in the

Treatment of Childhood Melanoma section. - Laboratory and imaging evaluation. Patients who present with conventional or adult-type melanoma should undergo laboratory and imaging evaluations based on adult guidelines. For more information, see the

Stage Information for Melanoma section in Melanoma Treatment. In contrast, patients who are diagnosed with spitzoid melanomas have a low risk of recurrence and excellent clinical outcomes and do not require extensive radiographic evaluation either at diagnosis or follow-up.[13 ]

A Children's Oncology Group–led panel of experts from different specialties have developed recommendations for the diagnostic evaluation and surgical management of cutaneous melanomas, atypical Spitz tumors, and non-Spitz melanocytic tumors.[

References:

- Berk DR, LaBuz E, Dadras SS, et al.: Melanoma and melanocytic tumors of uncertain malignant potential in children, adolescents and young adults--the Stanford experience 1995-2008. Pediatr Dermatol 27 (3): 244-54, 2010 May-Jun.

- Cerroni L, Barnhill R, Elder D, et al.: Melanocytic tumors of uncertain malignant potential: results of a tutorial held at the XXIX Symposium of the International Society of Dermatopathology in Graz, October 2008. Am J Surg Pathol 34 (3): 314-26, 2010.

- Cordoro KM, Gupta D, Frieden IJ, et al.: Pediatric melanoma: results of a large cohort study and proposal for modified ABCD detection criteria for children. J Am Acad Dermatol 68 (6): 913-25, 2013.

- Ferrari A, Lopez Almaraz R, Reguerre Y, et al.: Cutaneous melanoma in children and adolescents: The EXPeRT/PARTNER diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations. Pediatr Blood Cancer 68 (Suppl 4): e28992, 2021.

- Arjunan A, Wardrop M, Malek MM, et al.: Treatment outcomes following partial shave biopsy of atypical and malignant melanocytic tumors in pediatric patients. Melanoma Res 34 (6): 544-548, 2024.

- Shah NC, Gerstle JT, Stuart M, et al.: Use of sentinel lymph node biopsy and high-dose interferon in pediatric patients with high-risk melanoma: the Hospital for Sick Children experience. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 28 (8): 496-500, 2006.

- Kayton ML, La Quaglia MP: Sentinel node biopsy for melanocytic tumors in children. Semin Diagn Pathol 25 (2): 95-9, 2008.

- Swetter SM, Thompson JA, Albertini MR, et al.: NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Melanoma: Cutaneous, Version 2.2021. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 19 (4): 364-376, 2021.

- Ariyan CE, Coit DG: Clinical aspects of sentinel lymph node biopsy in melanoma. Semin Diagn Pathol 25 (2): 86-94, 2008.

- Pacella SJ, Lowe L, Bradford C, et al.: The utility of sentinel lymph node biopsy in head and neck melanoma in the pediatric population. Plast Reconstr Surg 112 (5): 1257-65, 2003.

- Lallas A, Kyrgidis A, Ferrara G, et al.: Atypical Spitz tumours and sentinel lymph node biopsy: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol 15 (4): e178-83, 2014.

- Lee S, Barnhill RL, Dummer R, et al.: TERT Promoter Mutations Are Predictive of Aggressive Clinical Behavior in Patients with Spitzoid Melanocytic Neoplasms. Sci Rep 5: 11200, 2015.

- Halalsheh H, Kaste SC, Navid F, et al.: The role of routine imaging in pediatric cutaneous melanoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 65 (12): e27412, 2018.

- Sargen MR, Barnhill RL, Elder DE, et al.: Evaluation and Surgical Management of Pediatric Cutaneous Melanoma and Atypical Spitz and Non-Spitz Melanocytic Tumors (Melanocytomas): A Report From Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 43 (9): 1157-1167, 2025.

Molecular Features

Accurate diagnosis of pediatric melanocytic lesions is essential for optimal risk stratification and treatment planning.

Melanoma-related conditions with malignant potential that arise in the pediatric population can be classified into the following three general groups:[

- Spitzoid melanocytic tumors ranging from atypical Spitz tumors to spitzoid melanomas.

- Melanoma arising in older adolescents that shares characteristics with adult melanoma (i.e., conventional melanoma).

- Large/giant congenital melanocytic nevus.

Lesions categorized as Spitz lesions are challenging to diagnose. Morphological assessment alone has significant limitations, and there is low interobserver expert agreement.[

Genomic alterations involving multiple genes have been reported in melanocytic lesions. The characteristics of each tumor are summarized in

- The genomic landscape of spitzoid melanomas is characterized by kinase gene fusions involving various genes, including RET, MAP3K8, ROS1, NTRK1, ALK, MET, and BRAF.[

3 ,4 ,5 ,6 ] These fusion genes have been reported in approximately 50% of cases and occur in a mutually exclusive manner.[1 ,4 ] - In a retrospective analysis of spitzoid tumors from 49 patients, whole-genome and transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) found in-frame fusions or C-terminal truncations of MAP3K8 in 33% of cases.[

6 ] - TERT promoter variants are uncommon in spitzoid melanocytic lesions and were observed in only 4 of 56 patients evaluated in one series. However, each of the four cases with TERT promoter variants experienced hematogenous metastases and died. This finding supports the potential for TERT promoter variants to predict aggressive clinical behavior in children with spitzoid melanocytic neoplasms, but additional study is needed to define the role of wild-type TERT promoter status in predicting clinical behavior in patients with primary site spitzoid tumors.[

4 ] - A retrospective analysis of 352 cases of Spitz nevi identified oncogenic drivers in 76% of the patients.[

7 ] No microscopic features allowed the reliable prediction of ROS1 and NTRK1 overexpressing cases. In contrast, a plexiform pattern was associated with ALK overexpression. The pseudo-schwannoma variant was highly suggestive of NTRK3-rearranged cases. Atypical/malignant tumor, severe cellular atypia, and p16 loss were associated with MAP3K8 rearrangements. Sheet-like architecture and marked fibrosis of the stroma were associated with BRAF fusions.

In another study, 128 lesions were classified as Spitz tumors based on morphology (80 Spitz tumors, 26 Spitz melanomas, 22 melanomas with Spitz features).[

- Kinase fusions or truncations were present in 81% of Spitz tumor cases and in 77% of Spitz melanoma cases. By comparison, 84% of melanomas with Spitz features had BRAF, NRAS, or NF1 variants, and 61% of these had TERT promoter variants.

- Among patients in the Spitz tumor group whose melanoma recurred, one patient diagnosed with a BRAF V600E variant and a TERT promoter variant developed a distant recurrence and died. A second patient with a MAP3K8 fusion had a local recurrence.

- Two patients with Spitz melanoma had recurrences and both had BRAF V600E variants.

- Of the three patients in the melanoma with spitzoid features group who had a recurrence, all had either a BRAF or NRAS variant with a concomitant TERT promoter variant.

- After reclassifying these patients by their clinical and genomic characteristics, and by incorporating the BRAF or NRAS variants into the melanoma with Spitz features category, a significant difference in recurrence-free survival rates could be detected among the groups with Spitz tumors. This finding suggests that incorporation of genomic features can greatly improve the classification of these lesions.

Conventional melanoma. The genomic landscape of conventional melanoma in children is represented by many of the genomic alterations that are found in adults with melanoma.[

Large congenital melanocytic nevi. Large congenital melanocytic nevi are reported to have activating NRAS Q61 variants with no other recurring variants noted.[

Integrating genomic analysis in the evaluation of pediatric melanocytic lesions can optimize diagnostic accuracy and provide important prognostic information for the treating physician. In a prospective registry of 70 patients with pediatric melanocytic lesions, the use of an integrated clinicopathological and genomic assessment optimized the pathological diagnosis and improved the ability to predict clinical outcomes in these patients.[

- Atypical Spitz tumor/Spitz melanoma.

- Patients with atypical Spitz tumors/Spitz melanomas were younger and had tumors predominantly located in the extremities.

- Genomic lesions in these patients were characterized by kinase fusions most often involving MAP3K8 and ALK.

- Even though 62% of patients who had nodes sampled had nodal disease, none developed distant metastases and two developed locoregional recurrences.

- Of the 33 patients tested, none of them had TERT promoter variants. However, CDKN2A was deleted in 15 patients. These findings suggest that TERT promoter variants might be better predictors of aggressive clinical behavior (development of metastases) in these lesions.

- Conventional melanoma.

- Patients with conventional melanoma (n = 17) were older and their tumors were more commonly located on the scalp or trunk.

- Seven of 12 patients had a positive sentinel node.

- Eleven of 17 patients had BRAF V600E variants.

- Seven of 16 patients had TERT promoter variants, and three of these patients died.

- Giant nevi.

- Of the four patients with melanoma arising in a giant nevi, all had NRAS Q61 variants and all died of their disease.

| Tumor | Affected Gene |

|---|---|

| Melanoma | BRAF,NRAS,KIT, NF1 |

| Spitz melanoma | Kinase fusions (RET,ROS,MET,ALK,BRAF,MAP3K8,NTRK1);BAP1loss in the presence ofBRAFvariant |

| Spitz nevus | HRAS;BRAFandNRAS(uncommon); kinase fusions (ROS,ALK,NTRK1,BRAF,RET,MAP3K8) |

| Acquired nevus | BRAF |

| Dysplastic nevus | BRAF,NRAS |

| Blue nevus | GNAQ |

| Ocular melanoma | GNAQ |

| Congenital nevi | NRAS |

References:

- Lu C, Zhang J, Nagahawatte P, et al.: The genomic landscape of childhood and adolescent melanoma. J Invest Dermatol 135 (3): 816-23, 2015.

- Gerami P, Busam K, Cochran A, et al.: Histomorphologic assessment and interobserver diagnostic reproducibility of atypical spitzoid melanocytic neoplasms with long-term follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol 38 (7): 934-40, 2014.

- Wiesner T, He J, Yelensky R, et al.: Kinase fusions are frequent in Spitz tumours and spitzoid melanomas. Nat Commun 5: 3116, 2014.

- Lee S, Barnhill RL, Dummer R, et al.: TERT Promoter Mutations Are Predictive of Aggressive Clinical Behavior in Patients with Spitzoid Melanocytic Neoplasms. Sci Rep 5: 11200, 2015.

- Yeh I, Botton T, Talevich E, et al.: Activating MET kinase rearrangements in melanoma and Spitz tumours. Nat Commun 6: 7174, 2015.

- Newman S, Fan L, Pribnow A, et al.: Clinical genome sequencing uncovers potentially targetable truncations and fusions of MAP3K8 in spitzoid and other melanomas. Nat Med 25 (4): 597-602, 2019.

- Kervarrec T, Pissaloux D, Tirode F, et al.: Morphologic features in a series of 352 Spitz melanocytic proliferations help predict their oncogenic drivers. Virchows Arch 480 (2): 369-382, 2022.

- Quan VL, Zhang B, Zhang Y, et al.: Integrating Next-Generation Sequencing with Morphology Improves Prognostic and Biologic Classification of Spitz Neoplasms. J Invest Dermatol 140 (8): 1599-1608, 2020.

- Wilmott JS, Johansson PA, Newell F, et al.: Whole genome sequencing of melanomas in adolescent and young adults reveals distinct mutation landscapes and the potential role of germline variants in disease susceptibility. Int J Cancer 144 (5): 1049-1060, 2019.

- Charbel C, Fontaine RH, Malouf GG, et al.: NRAS mutation is the sole recurrent somatic mutation in large congenital melanocytic nevi. J Invest Dermatol 134 (4): 1067-74, 2014.

- Kinsler VA, Thomas AC, Ishida M, et al.: Multiple congenital melanocytic nevi and neurocutaneous melanosis are caused by postzygotic mutations in codon 61 of NRAS. J Invest Dermatol 133 (9): 2229-36, 2013.

- Pappo AS, McPherson V, Pan H, et al.: A prospective, comprehensive registry that integrates the molecular analysis of pediatric and adolescent melanocytic lesions. Cancer 127 (20): 3825-3831, 2021.

Prognosis and Prognostic Factors

Children and adolescents with melanoma generally have a favorable outcome.

| Age (y) | 5-Year Relative Survival Rate (%) | Lower 95% Confidence Interval | Upper 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| a Adapted from the National Childhood Cancer Registry. NCCR*Explorer: An interactive website for NCCR cancer statistics [Internet]. National Cancer Institute; 2023 Sep 7. [updated: 2023 Sep 8; cited 2024 Aug 12]. Available from: https://nccrexplorer.ccdi.cancer.gov. | |||

| Age <1 | 85 | 63 | 94 |

| Ages 1–4 | 83 | 71 | 90 |

| Ages 5–9 | 99 | 95 | 100 |

| Ages 10–14 | 95 | 90 | 97 |

| Ages 15–19 | 97 | 95 | 99 |

Pediatric melanoma shares many similarities with adult melanoma, and the prognosis depends on disease stage.[

The outcome for patients with nodal disease is intermediate, with about 60% expected to survive long term.[

Children younger than 10 years who have melanoma often present with the following:[

- Poor prognostic features.

- Non-White races.

- Head and neck primary tumors.

- Thicker primary lesions.

- Higher incidence of spitzoid morphology vascular invasion and nodal metastases.

- Syndromes that predispose them to melanoma.

The use of sentinel lymph node biopsy for staging pediatric melanoma has become widespread. Primary tumor thickness and ulceration have been correlated with a higher incidence of nodal involvement.[

- Younger patients appear to have a higher incidence of nodal involvement, but this finding does not appear to significantly impact clinical outcomes.[

7 ,9 ] - In other series of pediatric melanoma, a higher incidence of nodal involvement did not appear to impact survival.[

10 ,11 ,12 ] - In a retrospective cohort study from the National Cancer Database, all records of patients with an index diagnosis of melanoma from 1998 to 2011 were reviewed. The data were abstracted from medical records, operative reports, and pathology reports and did not undergo central review. A total of 350,928 patients with adequate information were identified; 306 patients were aged 1 to 10 years (pediatric), and 3,659 patients were aged 11 to 20 years (adolescent).[

13 ]- Pediatric patients had longer overall survival (OS) than adolescent patients (hazard ratio [HR], 0.50; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.25–0.98) and patients older than 20 years (HR, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.06–0.21).

- Adolescents had longer OS than adults.

- No difference in OS was found between pediatric node-positive patients and node-negative patients.

- In pediatric patients, sentinel lymph node biopsy and completion of lymph node dissection were not associated with increased OS.

- In adolescents, nodal positivity was a significant negative prognostic indicator (HR, 4.82; 95% CI, 3.38–6.87).

The association of lesion thickness with clinical outcome is controversial in pediatric melanoma.[

References:

- National Cancer Institute: NCCR*Explorer: An interactive website for NCCR cancer statistics. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Available online . Last accessed February 25, 2025. - Paradela S, Fonseca E, Pita-Fernández S, et al.: Prognostic factors for melanoma in children and adolescents: a clinicopathologic, single-center study of 137 Patients. Cancer 116 (18): 4334-44, 2010.

- Wong JR, Harris JK, Rodriguez-Galindo C, et al.: Incidence of childhood and adolescent melanoma in the United States: 1973-2009. Pediatrics 131 (5): 846-54, 2013.

- Strouse JJ, Fears TR, Tucker MA, et al.: Pediatric melanoma: risk factor and survival analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology and end results database. J Clin Oncol 23 (21): 4735-41, 2005.

- Brecht IB, Garbe C, Gefeller O, et al.: 443 paediatric cases of malignant melanoma registered with the German Central Malignant Melanoma Registry between 1983 and 2011. Eur J Cancer 51 (7): 861-8, 2015.

- Lange JR, Palis BE, Chang DC, et al.: Melanoma in children and teenagers: an analysis of patients from the National Cancer Data Base. J Clin Oncol 25 (11): 1363-8, 2007.

- Moore-Olufemi S, Herzog C, Warneke C, et al.: Outcomes in pediatric melanoma: comparing prepubertal to adolescent pediatric patients. Ann Surg 253 (6): 1211-5, 2011.

- Mu E, Lange JR, Strouse JJ: Comparison of the use and results of sentinel lymph node biopsy in children and young adults with melanoma. Cancer 118 (10): 2700-7, 2012.

- Balch CM, Soong SJ, Gershenwald JE, et al.: Age as a prognostic factor in patients with localized melanoma and regional metastases. Ann Surg Oncol 20 (12): 3961-8, 2013.

- Gibbs P, Moore A, Robinson W, et al.: Pediatric melanoma: are recent advances in the management of adult melanoma relevant to the pediatric population. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 22 (5): 428-32, 2000 Sep-Oct.

- Livestro DP, Kaine EM, Michaelson JS, et al.: Melanoma in the young: differences and similarities with adult melanoma: a case-matched controlled analysis. Cancer 110 (3): 614-24, 2007.

- Han D, Zager JS, Han G, et al.: The unique clinical characteristics of melanoma diagnosed in children. Ann Surg Oncol 19 (12): 3888-95, 2012.

- Lorimer PD, White RL, Walsh K, et al.: Pediatric and Adolescent Melanoma: A National Cancer Data Base Update. Ann Surg Oncol 23 (12): 4058-4066, 2016.

- Rao BN, Hayes FA, Pratt CB, et al.: Malignant melanoma in children: its management and prognosis. J Pediatr Surg 25 (2): 198-203, 1990.

- Aldrink JH, Selim MA, Diesen DL, et al.: Pediatric melanoma: a single-institution experience of 150 patients. J Pediatr Surg 44 (8): 1514-21, 2009.

- Tcheung WJ, Marcello JE, Puri PK, et al.: Evaluation of 39 cases of pediatric cutaneous head and neck melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol 65 (2): e37-42, 2011.

- Ferrari A, Bisogno G, Cecchetto G, et al.: Cutaneous melanoma in children and adolescents: the Italian rare tumors in pediatric age project experience. J Pediatr 164 (2): 376-82.e1-2, 2014.

- Stanelle EJ, Busam KJ, Rich BS, et al.: Early-stage non-Spitzoid cutaneous melanoma in patients younger than 22 years of age at diagnosis: long-term follow-up and survival analysis. J Pediatr Surg 50 (6): 1019-23, 2015.

- Lohmann CM, Coit DG, Brady MS, et al.: Sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with diagnostically controversial spitzoid melanocytic tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 26 (1): 47-55, 2002.

- Su LD, Fullen DR, Sondak VK, et al.: Sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with problematic spitzoid melanocytic lesions: a report on 18 patients. Cancer 97 (2): 499-507, 2003.

Special Considerations for the Treatment of Children With Cancer

Cancer in children and adolescents is rare, although the overall incidence has slowly increased since 1975.[

- Primary care physicians.

- Pediatric surgeons.

- Pathologists.

- Pediatric radiation oncologists.

- Pediatric medical oncologists and hematologists.

- Ophthalmologists.

- Rehabilitation specialists.

- Pediatric oncology nurses.

- Social workers.

- Child-life professionals.

- Psychologists.

- Nutritionists.

For specific information about supportive care for children and adolescents with cancer, see the summaries on

The American Academy of Pediatrics has outlined guidelines for pediatric cancer centers and their role in the treatment of children and adolescents with cancer.[

Dramatic improvements in survival have been achieved for children and adolescents with cancer. Between 1975 and 2020, childhood cancer mortality decreased by more than 50%.[

Childhood cancer is a rare disease, with about 15,000 cases diagnosed annually in the United States in individuals younger than 20 years.[

The designation of a rare tumor is not uniform among pediatric and adult groups. In adults, rare cancers are defined as those with an annual incidence of fewer than six cases per 100,000 people. They account for up to 24% of all cancers diagnosed in the European Union and about 20% of all cancers diagnosed in the United States.[

- A consensus effort between the European Union Joint Action on Rare Cancers and the European Cooperative Study Group for Rare Pediatric Cancers estimated that 11% of all cancers in patients younger than 20 years could be categorized as very rare. This consensus group defined very rare cancers as those with annual incidences of fewer than two cases per 1 million people. However, three additional histologies (thyroid carcinoma, melanoma, and testicular cancer) with incidences of more than two cases per 1 million people were also included in the very rare group due to a lack of knowledge and expertise in the management of these tumors.[

9 ] - The Children's Oncology Group defines rare pediatric cancers as those listed in the International Classification of Childhood Cancer subgroup XI, which includes thyroid cancers, melanomas and nonmelanoma skin cancers, and multiple types of carcinomas (e.g., adrenocortical carcinomas, nasopharyngeal carcinomas, and most adult-type carcinomas such as breast cancers and colorectal cancers).[

10 ] These diagnoses account for about 5% of the cancers diagnosed in children aged 0 to 14 years and about 27% of the cancers diagnosed in adolescents aged 15 to 19 years.[4 ]Most cancers in subgroup XI are either melanomas or thyroid cancers, with other cancer types accounting for only 2% of the cancers diagnosed in children aged 0 to 14 years and 9.3% of the cancers diagnosed in adolescents aged 15 to 19 years.

These rare cancers are extremely challenging to study because of the relatively few patients with any individual diagnosis, the predominance of rare cancers in the adolescent population, and the small number of clinical trials for adolescents with rare cancers.

Information about these tumors may also be found in sources relevant to adults with cancer, such as

References:

- Smith MA, Seibel NL, Altekruse SF, et al.: Outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer: challenges for the twenty-first century. J Clin Oncol 28 (15): 2625-34, 2010.

- American Academy of Pediatrics: Standards for pediatric cancer centers. Pediatrics 134 (2): 410-4, 2014.

Also available online . Last accessed February 25, 2025. - Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC, et al.: Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer 120 (16): 2497-506, 2014.

- National Cancer Institute: NCCR*Explorer: An interactive website for NCCR cancer statistics. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Available online . Last accessed February 25, 2025. - Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute: SEER*Explorer: An interactive website for SEER cancer statistics. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Available online . Last accessed December 30, 2024. - Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, et al.: Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 64 (2): 83-103, 2014 Mar-Apr.

- Gatta G, Capocaccia R, Botta L, et al.: Burden and centralised treatment in Europe of rare tumours: results of RARECAREnet-a population-based study. Lancet Oncol 18 (8): 1022-1039, 2017.

- DeSantis CE, Kramer JL, Jemal A: The burden of rare cancers in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin 67 (4): 261-272, 2017.

- Ferrari A, Brecht IB, Gatta G, et al.: Defining and listing very rare cancers of paediatric age: consensus of the Joint Action on Rare Cancers in cooperation with the European Cooperative Study Group for Pediatric Rare Tumors. Eur J Cancer 110: 120-126, 2019.

- Pappo AS, Krailo M, Chen Z, et al.: Infrequent tumor initiative of the Children's Oncology Group: initial lessons learned and their impact on future plans. J Clin Oncol 28 (33): 5011-6, 2010.

Treatment of Childhood Melanoma

The European Cooperative Study Group for Pediatric Rare Tumors within the PARTNER project (Paediatric Rare Tumours Network - European Registry) has published recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of children and adolescents with cutaneous melanoma. Some of these recommendations have been incorporated and summarized in the sections below.[

Treatment options for childhood melanoma include the following:

-

Surgery and, in certain cases, sentinel lymph node biopsy and lymph node dissection. -

Immune checkpoint inhibitors or BRAF/MEK inhibitors .

Surgery

Surgery is the treatment of choice for patients with localized melanoma. Current guidelines recommend margins of resection as follows:

- 0.5 cm for melanoma in situ.

- 1 cm for melanoma thickness of less than 1 mm.

- 1 cm to 2 cm for melanoma thickness of 1.01 mm to 2 mm.

- 2 cm for tumor thickness of greater than 2 mm.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy should be considered in patients with thin lesions (≤1 mm) and ulceration, mitotic rate greater than 1/mm2, young age, and lesions larger than 1 mm with or without adverse features. Younger patients have a higher incidence of sentinel lymph node positivity, and this feature may adversely affect clinical outcomes.[

If the sentinel lymph node is positive, the option to undergo a complete lymph node dissection should be discussed. One adult trial included 1,934 patients with a positive sentinel node, identified by either immunohistochemistry or polymerase chain reaction. The patients were randomly assigned to undergo either complete lymph node dissection or observation. The 3-year melanoma-specific survival rate was similar in both groups (86%), whereas the disease-free survival (DFS) rate was slightly higher in the dissection group (68% vs. 63%; P = .05). This advantage in DFS was related to a decrease in the rate of nodal recurrences because there was no difference in the distant metastases–free survival rates. It remains unknown how these results will affect the future surgical management of children and adolescents with melanoma.[

Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors or BRAF/MEK Inhibitors

Targeted therapies and immunotherapy that have been effective in adults with melanoma should be pursued in pediatric patients with conventional melanoma and metastatic, recurrent, or progressive disease.

Evidence (targeted therapy and immunotherapy):

- A phase I trial of ipilimumab in children and adolescents, at a dose of 5 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks for four cycles, enrolled 12 patients with melanoma.[

6 ]- One patient had prolonged stable disease.

- This treatment demonstrated a similar toxicity profile as that seen in adults.

- A phase II study of ipilimumab for adolescents with melanoma failed to achieve accrual goals and was closed. However, there was reported activity in patients with melanoma who were aged 12 to 17 years, with a similar safety profile as that seen in adults.[

7 ][Level of evidence B4]- At 1 year, three of four patients who received 3 mg/kg and five of eight patients who received 10 mg/kg were alive.

- Two patients who received 10 mg/kg had partial responses, and one patient who received 3 mg/kg had stable disease.

- In adults with completely resected stage III cutaneous melanoma, prolonged DFS and overall survival have been seen with ipilimumab given at a dose of 10 mg/kg every 3 weeks for four doses, followed by one dose every 3 months for up to 3 years. This regimen caused little impairment in health-related quality of life.

- In a phase I/II trial of nivolumab for children and young adults with relapsed or refractory solid tumors or lymphoma, patients were treated with a dose of 3 mg/kg every 14 days.[

8 ]- The one patient with melanoma did not respond to therapy.

- An open-label, single-arm, phase I/II trial of pembrolizumab for pediatric patients with advanced melanoma or programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)–positive, advanced, relapsed, or refractory solid tumors or lymphoma reported the following:[

9 ]- Eight patients with melanoma were enrolled, and no responses were observed in these patients.

- Five of these patients were PD-L1 negative.

- The Children's Oncology Group conducted a phase I/II trial of ipilimumab and nivolumab in 55 children and young adults with refractory or recurrent solid tumors.[

10 ]- The study identified a recommended phase II dose of 3 mg/kg for nivolumab and 1 mg/kg for ipilimumab.

- No patients with melanoma were enrolled in the trial. However, partial responses were seen in one patient with rhabdomyosarcoma and one patient with Ewing sarcoma.

- A retrospective review identified 99 patients with melanoma (aged 18 years or younger) who were treated with systemic therapy at 15 Italian academic centers. Eighty-one patients received anti–PD-1 therapy. The median age was 14 years (range, 2–18 years), and 37 patients were aged 12 years or younger. Thirty-eight patients received anti–PD-1 therapy in the adjuvant setting.[

11 ]- Of the patients who received adjuvant anti–PD-1 therapy, the 3-year progression-free survival rate was 70.6%, and the overall survival (OS) rate was 81.1%.

- Of the 56 patients who received systemic therapy for advanced disease, 43 received first-line anti–PD-1–based therapy, while 12 patients received a second line, and 5 patients received a third line. Among patients who received first-line therapy with anti–PD-1 monotherapy, the objective response rate was 25%, and the 3-year OS rate was 34%.

- Toxicities were consistent with previous studies that included adult patients with melanoma.

- Dabrafenib and trametinib have been studied in two trials for pediatric patients with BRAF V600-altered low-grade gliomas. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved this combination for this indication.[

12 ,13 ] The FDA has also approved this combination for the treatment of patients with melanoma.

No trials have been conducted specifically for the treatment of pediatric patients with melanoma. However, the FDA has approved the following immune and targeted therapies for pediatric and adolescent patients with melanoma based on studies of adult populations with or without pediatric participants:

- Based on the positive results of two randomized clinical trials, the FDA approved adjuvant pembrolizumab for the treatment of patients aged 12 years and older with resected stage IIb, IIc, and III melanoma.[

14 ,15 ] - Based on the positive results of two randomized clinical trials, the FDA approved adjuvant nivolumab for the treatment of patients aged 12 years and older with resected stage IIb to IV melanoma.[

16 ,17 ] - Based on the positive results of one adult randomized clinical trial, the FDA approved nivolumab and ipilimumab for the treatment of children aged 12 years and older with unresectable or metastatic melanoma.[

18 ] - Based on the positive results of one randomized clinical trial, the FDA approved nivolumab with relatlimab for the treatment of children aged 12 years and older with unresectable or metastatic melanoma.[

19 ] - Although there have not been any prospective clinical trials using BRAF/MEK inhibitors in children and adolescents with melanoma, two adult studies have shown that the adjuvant combination of dabrafenib and trametinib results in a significantly lower risk of recurrence in patients with surgically resected stage III melanoma and in patients with previously untreated BRAF V600-altered metastatic melanoma.[

20 ,21 ] The FDA granted accelerated approval to this drug combination for the treatment of patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma who have BRAF V600E or V600K variants and for the adjuvant treatment of patients with melanoma who have BRAF V600E or V600K variants.

For more information, see

References:

- Ferrari A, Lopez Almaraz R, Reguerre Y, et al.: Cutaneous melanoma in children and adolescents: The EXPeRT/PARTNER diagnostic and therapeutic recommendations. Pediatr Blood Cancer 68 (Suppl 4): e28992, 2021.

- Sargen MR, Barnhill RL, Elder DE, et al.: Evaluation and Surgical Management of Pediatric Cutaneous Melanoma and Atypical Spitz and Non-Spitz Melanocytic Tumors (Melanocytomas): A Report From Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 43 (9): 1157-1167, 2025.

- Mu E, Lange JR, Strouse JJ: Comparison of the use and results of sentinel lymph node biopsy in children and young adults with melanoma. Cancer 118 (10): 2700-7, 2012.

- Han D, Zager JS, Han G, et al.: The unique clinical characteristics of melanoma diagnosed in children. Ann Surg Oncol 19 (12): 3888-95, 2012.

- Eggermont AM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob JJ, et al.: Prolonged Survival in Stage III Melanoma with Ipilimumab Adjuvant Therapy. N Engl J Med 375 (19): 1845-1855, 2016.

- Merchant MS, Wright M, Baird K, et al.: Phase I Clinical Trial of Ipilimumab in Pediatric Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res 22 (6): 1364-70, 2016.

- Geoerger B, Bergeron C, Gore L, et al.: Phase II study of ipilimumab in adolescents with unresectable stage III or IV malignant melanoma. Eur J Cancer 86: 358-363, 2017.

- Davis KL, Fox E, Merchant MS, et al.: Nivolumab in children and young adults with relapsed or refractory solid tumours or lymphoma (ADVL1412): a multicentre, open-label, single-arm, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol 21 (4): 541-550, 2020.

- Geoerger B, Kang HJ, Yalon-Oren M, et al.: Pembrolizumab in paediatric patients with advanced melanoma or a PD-L1-positive, advanced, relapsed, or refractory solid tumour or lymphoma (KEYNOTE-051): interim analysis of an open-label, single-arm, phase 1-2 trial. Lancet Oncol 21 (1): 121-133, 2020.

- Davis KL, Fox E, Isikwei E, et al.: A Phase I/II Trial of Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab in Children and Young Adults with Relapsed/Refractory Solid Tumors: A Children's Oncology Group Study ADVL1412. Clin Cancer Res 28 (23): 5088-5097, 2022.

- Mandalà M, Ferrari A, Brecht IB, et al.: Efficacy of anti PD-1 therapy in children and adolescent melanoma patients (MELCAYA study). Eur J Cancer 211: 114305, 2024.

- Hargrave DR, Bouffet E, Tabori U, et al.: Efficacy and Safety of Dabrafenib in Pediatric Patients with BRAF V600 Mutation-Positive Relapsed or Refractory Low-Grade Glioma: Results from a Phase I/IIa Study. Clin Cancer Res 25 (24): 7303-7311, 2019.

- Bouffet E, Hansford JR, Garrè ML, et al.: Dabrafenib plus Trametinib in Pediatric Glioma with BRAF V600 Mutations. N Engl J Med 389 (12): 1108-1120, 2023.

- Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, et al.: Adjuvant Pembrolizumab versus Placebo in Resected Stage III Melanoma. N Engl J Med 378 (19): 1789-1801, 2018.

- Luke JJ, Rutkowski P, Queirolo P, et al.: Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy in completely resected stage IIB or IIC melanoma (KEYNOTE-716): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 399 (10336): 1718-1729, 2022.

- Kirkwood JM, Del Vecchio M, Weber J, et al.: Adjuvant nivolumab in resected stage IIB/C melanoma: primary results from the randomized, phase 3 CheckMate 76K trial. Nat Med 29 (11): 2835-2843, 2023.

- Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, et al.: Adjuvant Nivolumab versus Ipilimumab in Resected Stage III or IV Melanoma. N Engl J Med 377 (19): 1824-1835, 2017.

- Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al.: Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med 377 (14): 1345-1356, 2017.

- Tawbi HA, Schadendorf D, Lipson EJ, et al.: Relatlimab and Nivolumab versus Nivolumab in Untreated Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med 386 (1): 24-34, 2022.

- Robert C, Karaszewska B, Schachter J, et al.: Improved overall survival in melanoma with combined dabrafenib and trametinib. N Engl J Med 372 (1): 30-9, 2015.

- Long GV, Hauschild A, Santinami M, et al.: Adjuvant Dabrafenib plus Trametinib in Stage III BRAF-Mutated Melanoma. N Engl J Med 377 (19): 1813-1823, 2017.

Treatment Options Under Clinical Evaluation for Childhood Melanoma

Information about National Cancer Institute (NCI)–supported clinical trials can be found on the

The following is an example of a national and/or institutional clinical trial that is currently being conducted:

- NCT02332668 (A Study of Pembrolizumab [MK-3475] in Pediatric Participants With Advanced Melanoma or Advanced, Relapsed, or Refractory PD-L1-Positive Solid Tumors or Lymphoma [MK-3475-051/KEYNOTE-051]): This is a two-part study of pembrolizumab in pediatric participants who have either advanced melanoma or a programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1)-positive advanced, relapsed, or refractory solid tumor or lymphoma. Part 1 will find the maximum tolerated dose/maximum administered dose, confirm the dose, and find the recommended phase II dose for pembrolizumab therapy. Part 2 will further evaluate the safety and efficacy of the phase II dose recommended for pediatric patients.

Latest Updates to This Summary (04 / 03 / 2025)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Added

Added

Added

Added

This summary is written and maintained by the

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of pediatric melanoma. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Childhood Melanoma Treatment are:

- Denise Adams, MD (Children's Hospital Boston)

- Karen J. Marcus, MD, FACR (Dana-Farber of Boston Children's Cancer Center and Blood Disorders Harvard Medical School)

- William H. Meyer, MD

- Paul A. Meyers, MD (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center)

- Thomas A. Olson, MD (Aflac Cancer and Blood Disorders Center of Children's Healthcare of Atlanta - Egleston Campus)

- Arthur Kim Ritchey, MD (Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC)

- Carlos Rodriguez-Galindo, MD (St. Jude Children's Research Hospital)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board uses a

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Pediatric Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Childhood Melanoma Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at:

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either "standard" or "under clinical evaluation." These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our

Last Revised: 2025-04-03

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the

Healthwise, Healthwise for every health decision, and the Healthwise logo are trademarks of Ignite Healthwise, LLC.

Page Footer

I want to...

Audiences

Secure Member Sites

The Cigna Group Information

Disclaimer

Individual and family medical and dental insurance plans are insured by Cigna Health and Life Insurance Company (CHLIC), Cigna HealthCare of Arizona, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Illinois, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Georgia, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of North Carolina, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of South Carolina, Inc., and Cigna HealthCare of Texas, Inc. Group health insurance and health benefit plans are insured or administered by CHLIC, Connecticut General Life Insurance Company (CGLIC), or their affiliates (see

All insurance policies and group benefit plans contain exclusions and limitations. For availability, costs and complete details of coverage, contact a licensed agent or Cigna sales representative. This website is not intended for residents of New Mexico.