Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage

Plans through your employer

Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

Learn

Living or working abroad?

Childhood Vascular Tumors Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

Vascular Anomalies

Vascular anomalies are a spectrum of rare diseases classified as either vascular tumors or vascular malformations. Generally, vascular tumors are proliferative, while vascular malformations enlarge through expansion of a developmental anomaly without underlying proliferation.

Although these anomalies are not oncological, it is important for oncologists to understand the biology and clinical management of common vascular malformations. This is because many vascular malformations are caused by targetable somatic variants, which means that pediatric oncologists will be asked to help manage these lesions. While information about vascular malformations is covered at the beginning of this summary, the remainder of this summary focuses on tumors, not malformations.

Vascular Malformations

Vascular malformations are distinguished from vascular tumors by their low cell turnover and lack of invasiveness.[

In the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) classification, vascular malformations are subdivided according to vessel type.[

Slow-flow lesions include venous, lymphatic, capillary, or combined lesions. Complications from slow-flow lesions include pain, infection, bleeding, thrombosis, and organ dysfunction.

Regular monitoring and assessment of changes or development of symptoms is warranted in patients with vascular malformations. Treatment requires an interdisciplinary approach to care and includes observation, surgery, endovascular intervention, and medical management. Only a low level of evidence supports the choice of treatment between these options. Recurrence rates of these lesions are relatively high.[

Vascular malformations are most commonly caused by variants in the MAP2K/PIK3CA pathway. Most are activating somatic variants but, rarely, germline variants are identified. Approximately one-third to one-half of venous malformations result from somatic or, rarely, germline variants in the TEK (or TIE2) gene.[

Sirolimus was initially used to target the PI3K pathway in slow-flow malformations, leading to symptomatic improvement in many patients. It is unclear whether treatment reduces the size of lesions because there is usually considerable fluctuation in size, and treatment generally begins when lesions are enlarged. The use of sirolimus in venous and lymphatic malformations is supported by level C evidence (case series, other observational study designs, phase II studies).[

There is some support for targeted therapy in fast-flow malformations and complicated lymphatic anomalies that are caused by somatic and germline variants in the MAPK pathway, including gain of function variants in MAP2K1, KRAS, NRAS, and BRAF.[

Treatment Options Under Clinical Evaluation

Information about National Cancer Institute (NCI)-supported clinical trials can be found on the

The following are examples of national and/or institutional clinical trials that are currently being conducted:

- NCT04258046 (Trametinib in the Treatment of Complicated Extracranial Arterial Venous Malformation): This is a phase II study to assess the safety and efficacy of trametinib in the treatment of children and adults.

- NCT05125471 (Cobimetinib in Extracranial Arteriovenous Malformations [COBI-AVM Study]): This is a phase II study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of cobimetinib in the treatment of children and adults.

- NCT05948943 (Alpelisib in Pediatric and Adult Patients With Lymphatic Malformations Associated With a PIK3CA Variant): This is a phase II/III study of adults and children (aged 6–17 years) that will determine the dose of alpelisib in stage 1, followed by confirmation of efficacy and safety in stage 2 of the study.

References:

- Mulliken JB, Glowacki J: Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: a classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg 69 (3): 412-22, 1982.

- Lokmic Z, Mitchell GM, Koh Wee Chong N, et al.: Isolation of human lymphatic malformation endothelial cells, their in vitro characterization and in vivo survival in a mouse xenograft model. Angiogenesis 17 (1): 1-15, 2014.

- Wassef M, Blei F, Adams D, et al.: Vascular Anomalies Classification: Recommendations From the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. Pediatrics 136 (1): e203-14, 2015.

- van der Vleuten CJ, Kater A, Wijnen MH, et al.: Effectiveness of sclerotherapy, surgery, and laser therapy in patients with venous malformations: a systematic review. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 37 (4): 977-89, 2014.

- Soblet J, Limaye N, Uebelhoer M, et al.: Variable Somatic TIE2 Mutations in Half of Sporadic Venous Malformations. Mol Syndromol 4 (4): 179-83, 2013.

- Luks VL, Kamitaki N, Vivero MP, et al.: Lymphatic and other vascular malformative/overgrowth disorders are caused by somatic mutations in PIK3CA. J Pediatr 166 (4): 1048-54.e1-5, 2015.

- Keppler-Noreuil KM, Rios JJ, Parker VE, et al.: PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS): diagnostic and testing eligibility criteria, differential diagnosis, and evaluation. Am J Med Genet A 167A (2): 287-95, 2015.

- Adams DM, Trenor CC, Hammill AM, et al.: Efficacy and Safety of Sirolimus in the Treatment of Complicated Vascular Anomalies. Pediatrics 137 (2): e20153257, 2016.

- Hammer J, Seront E, Duez S, et al.: Sirolimus is efficacious in treatment for extensive and/or complex slow-flow vascular malformations: a monocentric prospective phase II study. Orphanet J Rare Dis 13 (1): 191, 2018.

- Maruani A, Tavernier E, Boccara O, et al.: Sirolimus (Rapamycin) for Slow-Flow Malformations in Children: The Observational-Phase Randomized Clinical PERFORMUS Trial. JAMA Dermatol 157 (11): 1289-1298, 2021.

- Venot Q, Blanc T, Rabia SH, et al.: Targeted therapy in patients with PIK3CA-related overgrowth syndrome. Nature 558 (7711): 540-546, 2018.

- Couto JA, Huang AY, Konczyk DJ, et al.: Somatic MAP2K1 Mutations Are Associated with Extracranial Arteriovenous Malformation. Am J Hum Genet 100 (3): 546-554, 2017.

- Dori Y, Smith C, Pinto E, et al.: Severe Lymphatic Disorder Resolved With MEK Inhibition in a Patient With Noonan Syndrome and SOS1 Mutation. Pediatrics 146 (6): , 2020.

- Nakano TA, Rankin AW, Annam A, et al.: Trametinib for Refractory Chylous Effusions and Systemic Complications in Children with Noonan Syndrome. J Pediatr 248: 81-88.e1, 2022.

- Homayun-Sepehr N, McCarter AL, Helaers R, et al.: KRAS-driven model of Gorham-Stout disease effectively treated with trametinib. JCI Insight 6 (15): , 2021.

- Foster JB, Li D, March ME, et al.: Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis effectively treated with MEK inhibition. EMBO Mol Med 12 (10): e12324, 2020.

- Chowers G, Abebe-Campino G, Golan H, et al.: Treatment of severe Kaposiform lymphangiomatosis positive for NRAS mutation by MEK inhibition. Pediatr Res 94 (6): 1911-1915, 2023.

- Lekwuttikarn R, Lim YH, Admani S, et al.: Genotype-Guided Medical Treatment of an Arteriovenous Malformation in a Child. JAMA Dermatol 155 (2): 256-257, 2019.

- Nicholson CL, Flanagan S, Murati M, et al.: Successful management of an arteriovenous malformation with trametinib in a patient with capillary-malformation arteriovenous malformation syndrome and cardiac compromise. Pediatr Dermatol 39 (2): 316-319, 2022.

- Cooke DL, Frieden IJ, Shimano KA: Angiographic evidence of response to trametinib therapy for a spinal cord arteriovenous malformation. J Vasc Anom (Phila) 2 (3): e018, 2021.

Available online . Last accessed July 6, 2023..

Childhood Vascular Tumors

Vascular tumors are proliferative tumors that can be benign or malignant. Growth and/or expansion of vascular tumors can cause clinical problems such as disfigurement, chronic pain, coagulopathies, organ dysfunction, and death.

The quality of evidence regarding childhood vascular tumors is limited by retrospective data collection, small sample size, cohort selection and participation bias, and heterogeneity of the disorders. Lack of consistent criteria and medical terminology has led to unreliable conclusions from the historical medical literature.[

In the past, limited treatment options were available, and efficacy was not validated in prospective clinical trials. Historically, therapies consisted of interventional and surgical procedures used to palliate symptoms. Limited medical therapies were available. Newer therapy options with propranolol and sirolimus are now available for the treatment of patients with complex vascular tumors. The first prospective clinical trial using propranolol for infantile hemangioma has been published, as well as the first prospective clinical trial that studied the effectiveness of sirolimus for complicated vascular anomalies, including vascular tumors.[

With a prevalence of 4% to 5%, infantile hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of infancy. Other vascular tumors are rare. The classification of these tumors has been difficult, especially in the pediatric population, because of their rarity, unusual morphologic appearance, diverse clinical behavior, and the lack of independent stratification for pediatric tumors. In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) updated the classification of soft tissue vascular tumors.[

The International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) classification of tumors is based on the WHO classification, but it uses more precise terminology and phenotypes. The General Assembly of the ISSVA adopted an updated classification system in 2014, with further additions in 2018 (

| Category | Vascular Tumor Type |

|---|---|

| NOS = not otherwise specified. | |

| a Adapted from the WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board.[ |

|

| Benign | Hemangioma NOS |

| Intramuscular hemangioma | |

| Arteriovenous hemangioma | |

| Venous hemangioma | |

| Epithelioid hemangioma | |

| Lymphangioma NOS | |

| Cystic lymphangioma | |

| Acquired tufted hemangioma | |

| Intermediate (locally aggressive) | Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma |

| Intermediate (rarely metastasizing) | Retiform hemangioendothelioma |

| Papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma | |

| Composite hemangioendothelioma | |

| Kaposi sarcoma | |

| Pseudomyogenic (epithelioid sarcoma–like) hemangioendothelioma | |

| Malignant | Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma NOS |

| Angiosarcoma | |

| Category | Vascular Tumor Type (Causal Genes) |

|---|---|

| a Adapted from ISSVA Classification of Vascular Anomalies. ©2018 International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. Available at " |

|

| b See the |

|

| c Tufted angioma and kaposiform hemangioendothelioma are a spectrum of the same entity and will be discussed together. | |

| Benign (type 1b) | Infantile hemangioma/hemangioma of infancy |

| Congenital hemangioma (GNAQ,GNA11) | |

| —Rapidly involuting (RICH) | |

| —Non-involuting (NICH) | |

| —Partially-involuting (PICH) | |

| Tufted angiomac | |

| Spindle cell hemangioma (IDH1,IDH2) | |

| Epithelioid hemangioma (FOS) | |

| Pyogenic granuloma (also known as lobular capillary hemangioma) (BRAF,RAS,GNA14) | |

| Others | |

| Locally aggressive or borderline | Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma (KHE) (GNA14) |

| Retiform hemangioendothelioma | |

| Papillary intralymphatic angioendothelioma (PILA), Dabska tumor | |

| Composite hemangioendothelioma | |

| Pseudomyogenic hemangioendothelioma (FOSB) | |

| Polymorphous hemangioendothelioma | |

| Hemangioendothelioma not otherwise specified | |

| Kaposi sarcoma | |

| Others | |

| Malignant | Angiosarcoma (MYC: postradiation therapy) |

| Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (EHE) (CAMTA1,TFE3) | |

| Others | |

References:

- Liberale C, Rozell-Shannon L, Moneghini L, et al.: Stop Calling Me Cavernous Hemangioma! A Literature Review on Misdiagnosed Bony Vascular Anomalies. J Invest Surg 35 (1): 141-150, 2022.

- Boulogeorgou K, Avramidou E, Koletsa T: Identifying erroneously used terms for vascular anomalies: A review of the English literature. Hippokratia 26 (4): 126-130, 2022.

- Hassanein AH, Mulliken JB, Fishman SJ, et al.: Evaluation of terminology for vascular anomalies in current literature. Plast Reconstr Surg 127 (1): 347-351, 2011.

- Léauté-Labrèze C, Hoeger P, Mazereeuw-Hautier J, et al.: A randomized, controlled trial of oral propranolol in infantile hemangioma. N Engl J Med 372 (8): 735-46, 2015.

- Adams DM, Trenor CC, Hammill AM, et al.: Efficacy and Safety of Sirolimus in the Treatment of Complicated Vascular Anomalies. Pediatrics 137 (2): e20153257, 2016.

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board: WHO Classification of Tumours. Volume 3: Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours. 5th ed., IARC Press, 2020.

- International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies: ISSVA Classification of Vascular Anomalies. Milwaukee, Wi: International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies, 2018.

Available online . Last accessed June 7, 2022. - Wassef M, Blei F, Adams D, et al.: Vascular Anomalies Classification: Recommendations From the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. Pediatrics 136 (1): e203-14, 2015.

Special Considerations for the Treatment of Children With Cancer

Cancer in children and adolescents is rare, although the overall incidence has slowly increased since 1975.[

- Primary care physicians.

- Pediatric surgeons.

- Transplant surgeons.

- Pathologists.

- Pediatric radiation oncologists.

- Pediatric medical oncologists and hematologists.

- Ophthalmologists.

- Rehabilitation specialists.

- Pediatric oncology nurses.

- Social workers.

- Child-life professionals.

- Psychologists.

- Nutritionists.

For specific information about supportive care for children and adolescents with cancer, see the summaries on

The American Academy of Pediatrics has outlined guidelines for pediatric cancer centers and their role in the treatment of children and adolescents with cancer.[

Dramatic improvements in survival have been achieved for children and adolescents with cancer.[

References:

- Smith MA, Seibel NL, Altekruse SF, et al.: Outcomes for children and adolescents with cancer: challenges for the twenty-first century. J Clin Oncol 28 (15): 2625-34, 2010.

- American Academy of Pediatrics: Standards for pediatric cancer centers. Pediatrics 134 (2): 410-4, 2014.

Also available online . Last accessed February 25, 2025. - Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC, et al.: Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer 120 (16): 2497-506, 2014.

- Childhood cancer. In: Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al., eds.: SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2010. National Cancer Institute, 2013, Section 28.

Also available online . Last accessed August 21, 2023. - Childhood cancer by the ICCC. In: Howlader N, Noone AM, Krapcho M, et al., eds.: SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2010. National Cancer Institute, 2013, Section 29.

Also available online . Last accessed August 21, 2023. - National Cancer Institute: NCCR*Explorer: An interactive website for NCCR cancer statistics. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Available online . Last accessed February 25, 2025. - Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute: SEER*Explorer: An interactive website for SEER cancer statistics. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Available online . Last accessed December 30, 2024.

Benign Tumors

Benign vascular tumors include the following:

-

Infantile hemangioma . -

Congenital hemangioma . -

Hepatic vascular tumors . -

Spindle cell hemangioma . -

Epithelioid hemangioma . -

Pyogenic granuloma (lobular capillary hemangioma) . -

Angiofibroma . -

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma .Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma is not included in the World Health Organization (WHO) classification or the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) classification of vascular tumors. It is included here because growing evidence reveals vascular differentiation and proliferation in these tumors with response to vascular remodeling and antiproliferative agents.

Infantile Hemangioma

Incidence and epidemiology

Infantile hemangiomas (IH) are the most common benign vascular tumor of infancy, occurring in 4% to 5% of infants. The true incidence is unknown.[

Infantile hemangiomas are more common in females, non-Hispanic White patients, and premature infants. Multiple hemangiomas are more common in infants who are the product of multiple gestations or in vitro fertilization.[

Clinical presentation

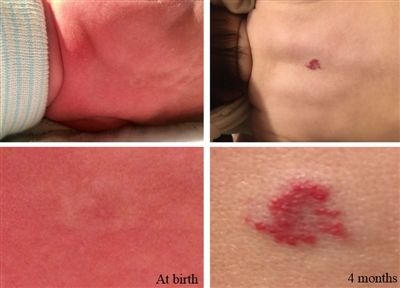

Most infantile hemangiomas are not present at birth, but precursor lesions such as telangiectasia or faint discoloration of the skin or hypopigmentation can often be seen. The lesion can be mistaken as a bruise from birth trauma or as a capillary malformation (port-wine stain) (see

Figure 1. The photos on the left depict the precursor lesion (faint color with halo). The photos on the right depict the hemangioma after proliferation (slightly raised with a brighter central color). Credit: Israel Fernandez-Pineda, M.D.

Infantile hemangiomas can be superficial in the dermis, deep in the subcutaneous tissue, combined, or in the viscera. Combined lesions are common and generally appear in the head and neck but can be anywhere on the body.

Infantile hemangiomas can be characterized as follows:

- Local: Most lesions are localized and noted to be in a well-defined area without evidence of a geometric pattern.

- Segmental: Most segmental hemangiomas occur in the head and neck region (

PHACE syndrome ) but can be seen in the genitourinary area, arm, chest, or legs(PELVIS/LUMBAR/SACRAL syndrome ).- Diffuse hemangiomas of the face demonstrate defined cutaneous patterns. Several studies have evaluated the distributions of these hemangiomas and found the following four distinct patterns or segments:

- Segment 1 involves the lateral forehead, anterior temporal scalp, and the lateral frontal scalp.

- Segments 2 and 3 are located over the maxillary and mandibular area.

- Segment 4 covers the medial frontal scalp, nose, and philtrum.

Two papers have noted this observation and suggest the involvement of neural crest derivatives in facial hemangioma development.[

10 ,11 ] Segmental hemangiomas commonly occur in females and are more likely associated with complications and other syndromes.[12 ,13 ]For information about PHACE syndrome or PELVIS/LUMBAR/SACRAL syndrome, see the

Syndromes associated with infantile hemangioma section. - Diffuse hemangiomas of the face demonstrate defined cutaneous patterns. Several studies have evaluated the distributions of these hemangiomas and found the following four distinct patterns or segments:

- Multiple: More than one lesion but noted in the past as greater than five lesions, because of the increased risk of visceral involvement (mostly the liver).

The cutaneous appearance of infantile hemangiomas is usually red to crimson, firm, and warm in the proliferative phase. The lesion then lightens centrally and becomes less warm and softer; it then flattens and loses its color. The process of involution can take several years and once involution has occurred, regrowth is uncommon. In two patients treated with growth hormone, regrowth after involution was noted.[

Ulceration is the most common complication of infantile hemangiomas, occurring in 10% to 15% of patients. Ulceration typically occurs during the proliferative phase, and it can lead to bleeding and secondary infections.[

Permanent sequelae, such as telangiectasia, anetodermal skin, redundant skin, and a persistent superficial component, can occur after hemangioma involution. Hemangiomas with a history of ulceration are more likely to cause scarring and potential local anatomical complications.[

Biology and histopathology

Most infantile hemangiomas occur sporadically. However, they may rarely be caused by an abnormality of chromosome 5 and present in an autosomal dominant pattern.[

The exact mechanism that causes the initial proliferation of blood vessels followed by involution of the vascular component of hemangioma and replacement of fibrofatty tissue is unknown. Several cell types have been isolated from hemangiomas: progenitor/stem cells (HemSC), endothelial cells (HemEC), pericytes (HemPericytes), and mast cells.[

HemSC represent a small percentage of proliferating hemangioma cells and have the ability for self renewal and multilineage differentiation. These cells differentiate into endothelial cells, adipocytes, and pericytes. When HemSC are implanted into immunodeficient mice, hemangioma-like lesions form and then spontaneously regress, similar to infantile hemangiomas.[

HemEC are plump, metabolically active, and resemble fetal endothelial cells in the proliferative phase. Evaluation of infantile hemangioma endothelial cells suggest that they are clonal in nature.[

HemPericytes surround the vasculature and are abundant in the proliferative phase. These cells express markers of pericytes and smooth muscle cells, such as neural-glial antigen 2 (NG2), platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFR-beta), calponin, alpha smooth muscle actin (SMA), and NOTCH3. HemPericytes are proangiogenic, as they express increased vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A), decreased angiopoietin-1 (ANGPT1), increased proliferation, increased vessel formation in vivo, and decreased ability to suppress proliferation.[

Mast cells are found largely in the early involuting phase, but they are also found in small numbers in the proliferative phase and at the end of involution. Their function in infantile hemangiomas is unknown but they have been shown to play a role in other skin tumors such as basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma.[

Provasculogenic factors are expressed during proliferation; these factors include VEGF, fibroblast growth factor (FGF), CD34, CD31, CD133, lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan receptor 1 (LYVE1), and insulin-like growth factor 2 (IGF-2).[

Hypoxia appears to have a critical role in the pathogenesis of hemangiomas. There is an association between hemangiomas and placental hypoxia, which is increased in prematurity, multiple pregnancies, and placental anomalies.[

Diagnostic evaluation

Infantile hemangiomas are usually diagnosed by the history and clinical appearance. Biopsy is rarely needed and performed only if there is an atypical appearance and/or atypical history and presentation. Imaging is not usually necessary, but diagnostic ultrasonography is beneficial if there is a deeper lesion without a cutaneous component and reveals a well-circumscribed, hypoechoic, high-flow lesion with a typical Doppler wave characteristic.[

Infantile hemangioma with minimal or arrested growth

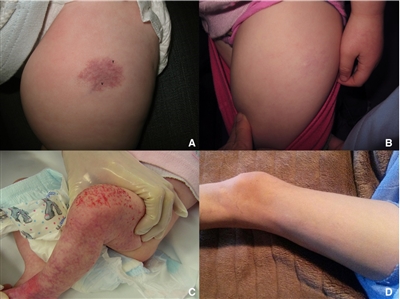

Infantile hemangioma with minimal or arrested growth (IH-MAG) is a variant of hemangioma that can be confused with capillary malformation because of their unusual characteristics. These hemangiomas are mostly fully formed at birth and are characterized by telangiectasia and venules with light and dark areas of skin coloration (see

Figure 2. Patient 4 at (A) presentation and (B) resolution. Patient 5 at (C) presentation and (D) resolution. Ma, E. H., Robertson, S. J., Chow, C. W., and Bekhor, P. S. (2017), Infantile Hemangioma with Minimal or Arrested Growth: Further Observations on Clinical and Histopathologic Findings of this Unique but Underrecognized Entity. Pediatr Dermatol, 34: 64–71. doi:10.1111/pde.13022. Used with permission.

Airway infantile hemangioma

Airway infantile hemangiomas are usually associated with segmental hemangiomas in a bearded distribution, which may include all or some of the following—the preauricular skin, mandible, lower lip, chin, or anterior neck. It is important for an otolaryngologist to proactively assess lesions in this distribution before signs of stridor occur. Airway infantile hemangioma incidence increases with a larger area of bearded involvement.[

Airway infantile hemangiomas can occur without skin lesions. A retrospective study of the Vascular Anomaly Database at the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh analyzed 761 cases of infantile hemangioma. Thirteen patients (1.7%) had subglottic hemangiomas. Of those 13 patients, 4 (30%) had bearded distributions, 2 (15%) had cutaneous hemangiomas, and 7 (55%) had no cutaneous lesions.[

Ophthalmologic involvement of hemangiomas

Periorbital hemangiomas can cause visual compromise.[

Two institutions in France and Canada performed a retrospective analysis of patients in a vascular anomalies practice. The investigators reviewed the records of all patients with a diagnosis of segmental facial or periorbital focal infantile hemangioma who had clinical photographs and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) available.[

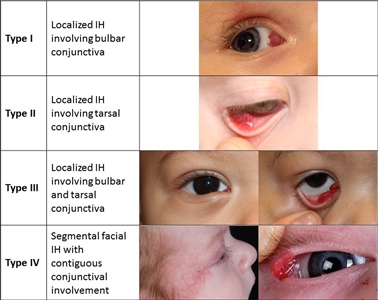

Infantile hemangiomas can occur in the conjunctiva (see

Figure 3. Proposed classification of infantile hemangiomas involving the conjunctiva. Theiler M, Baselga E, Gerth-Kahlert C, et al. Infantile hemangiomas with conjunctival involvement: An underreported occurrence. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:681–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.13305 Copyright © 2017 John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Syndromes associated with infantile hemangioma

PHACE syndrome

Posterior fossa–brain malformations; Hemangiomas; Arterial, Cardiac, and Eye abnormalities (PHACE) syndrome:

Figure 4. A large segmental infantile hemangioma (plaque-like) in a bearded distribution. This patient has an increased risk of PHACE syndrome, airway infantile hemangioma, and ulceration. A tracheostomy was placed secondary to a very diffuse airway hemangioma. Credit: Denise Adams, M.D. Garzon MC, Epstein LG, Heyer GL, et al.: PHACE Syndrome: Consensus-Derived Diagnosis and Care Recommendations. J Pediatr 178: 24-33.e2, 2016. PMID: 27659028

Consensus criteria for definite and possible PHACE syndrome were updated at an expert panel meeting, as follows:[

PHACE

- Posterior fossa abnormalities. Posterior fossa malformations include Dandy-Walker complex, cerebellar hypoplasia, atrophy, and dysgenesis/agenesis of the vermis. Effects of these anomalies include developmental delays and pituitary dysfunction.[

54 ] - Hemangiomas.[

53 ,55 ,56 ,57 ,58 ]- A large segmental hemangioma over the face and/or scalp with a surface area of 22 cm2 or greater (5 cm × 4.5 cm).

- A large segmental hemangioma of the neck, trunk, or proximal upper extremity.

Infants with two major criteria of PHACE (e.g., supraumbilical raphe and coarctation of the aorta) but lacking cutaneous infantile hemangiomas should undergo complete evaluation for PHACE.

- Arterial abnormalities. Cerebrovascular anomalies can include carotid artery abnormalities (including tortuosity) and absence, dilation/aneurysm, or narrowing of cerebral vessels. These anomalies, especially related to the carotid arteries, can lead to progressive arterial occlusion and even stroke. The risk categories are as follows:[

51 ,52 ,59 ,60 ,61 ]- Low risk: This category includes patients with arterial anomalies frequently seen in a general screening population. It also includes findings that have either no or very minimal clinical impact on patient outcome, even if rarely seen in the general population. Examples are persistent embryonic arteries, anomalous arterial origin or course, and circle of Willis variants.

- Intermediate risk: Includes patients with nonstenotic dysgenesis, including those with ectatic or segmentally enlarged arteries. It also includes patients with a narrowing or occlusion of arteries proximal to the circle of Willis, with no perceived hemodynamic risk. An evaluation of the patency of the circle of Willis is essential.

- High risk: This category includes patients with one or more of the following:

- Significant narrowing (>25%) or occlusion of principal cerebral vessels within or above the circle of Willis that results in an isolated circulation.

- Tandem or multiple arterial stenoses associated with complex blood flow that may potentially result in diminished cerebral perfusion. Patients with cerebrovascular stenosis in the setting of coarctation of the aorta are likely at higher risk of transient and permanent neurological ischemic events.

- Imaging findings in the brain parenchyma suggestive of chronic or silent ischemia, or progressive steno-occlusive disease. These parenchymal brain MRI findings include existing infarction, chronic or border zone ischemic changes, and presence of lenticulostriate collateral dilation or pial collaterals.

- Cardiac abnormalities. Aortic arch anomalies observed in PHACE syndrome are unusually complex, with involvement of the transverse and descending aorta arch. The arch obstruction is most often long-segment. The obstruction is frequently characterized by areas of arch narrowing with adjacent segments of marked aneurysmal dilatation.

- Eye abnormalities. Ophthalmologic anomalies can include microphthalmos, retinal vascular abnormalities, persistent fetal retinal vessels, exophthalmos, coloboma, and optic nerve atrophy. These abnormalities are rare and occur in 7% to 10% of patients.[

62 ]

A retrospective review identified midline rhabdomyomatous mesenchymal hamartomas and chin hamartomas in a small number of children with PHACE or

Diagnosis of PHACE syndrome requires clinical examination, cardiac evaluation with echocardiogram, ophthalmologic evaluation, and MRI/magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) of the head and neck. All patients with intermediate-risk and high-risk central nervous system (CNS) findings should be monitored by a neurologist and/or neurosurgeon. Coarctation of the aorta requires immediate cardiology consultation, and a cardiac MRI/MRA may be warranted. A report of two patients with retro-orbital infantile hemangiomas and arteriopathy suggested a possible new presentation of PHACE syndrome.[

Short- and long-term issues related to PHACE syndrome include the following:[

- Headache.

- May present at an early age.

- Can be severe.

- New-onset headaches should be evaluated for vasculopathy and/or cerebral ischemia.

- Neurology referral is recommended.

- Vasoconstrictive medications are contraindicated.

- Hearing loss and speech-language delays.

- Speech-language delays may be a consequence of hearing deficits, prolonged hospitalizations, or may occur because of other neurodevelopmental anomalies.

- Sensorineural hearing loss is the most common type, and it is usually ipsilateral to the infantile hemangioma, which may involve the ipsilateral cranial nerve VIII.

- Early detection is crucial.

- All patients with PHACE syndrome should undergo hearing screening as a newborn and at least one follow-up if initial screening is normal.

- Dysphagia, feeding disorders, speech disorders, and/or language delay.

- Increased in patients with posterior fossa malformations, lip/oropharynx or airway hemangiomas, hearing loss, and those with a history of cardiac surgery.

- Patients should undergo an initial speech language evaluation before age 24 months.

- Patients with feeding difficulties should be referred for evaluation by a pediatric speech-language pathologist at any age.

- Dysphagia may be secondary to the disease location (lip, oral cavity, and pharynx) or oral motor coordination.

- Endocrine abnormalities.

- Thyroid dysfunction and hypopituitarism resulting in growth hormone deficiency are the most frequently reported abnormalities.

- Other manifestations of hypopituitarism, including hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and adrenal insufficiency, have been described.

- Patients should undergo neonatal screening and repeat studies if symptomatic.

- Growth hormone deficiency: Most reported cases are associated with hypopituitarism with empty or partially empty sella turcica noted on MRI, but it may also occur without evidence of central nervous system malformations.

- Neonatal hypoglycemia can be a sign of hypopituitarism and should prompt additional endocrinologic evaluation.

- Other consequences of pituitary dysfunction include hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, manifesting with delayed pubertal onset and late-onset adrenal insufficiency. These findings emphasize the importance of focused assessment of height, weight, and developmental milestones in the care of children with PHACE.

- Dental abnormalities (enamel hypoplasia).

- A study of 18 children with PHACE or possible PHACE syndrome revealed that 28% of patients had enamel hypoplasia. All of the affected children had intraoral hemangiomas. Five of 11 (45%) patients with intraoral hemangiomas had enamel defects. Children with enamel hypoplasia are at increased risk of developing caries.

- Patients should be examined for the presence of intraoral hemangiomas. If they are present, patients should be referred to a pediatric dentist by age 1 year for early screening and management.

- Long-term outcomes and quality of life.

- An international group of experts published a report of a multicenter study that used cross-sectional interviews and chart review to examine long-term outcomes and quality of life for patients older than 10 years with PHACE syndrome.[

68 ] Individuals were defined as having definite PHACE by previously reported guidelines.[47 ] This was the largest cohort of adolescents and adults with PHACE. Of 153 individuals who were contacted, 104 participated in the study (68%). The median age was 14 years (range, 10–77 years). This study found that PHACE syndrome was associated with long-term, mild-to-severe morbidities, including infantile hemangioma residua (94.1%), headaches/migraines (72.1%), learning differences (45.1%), and progressive arteriopathy (29.4%). Additional findings from the study are reported inTable 3 .Most patients with hemangioma residua were satisfied or very satisfied with their appearance (89.5%). Those with surgery and/or ulceration were less likely to report a minimal impact on self-confidence. Of the 68 patients with arteriopathy and available follow-up imaging, 6 (8.8%) developed moyamoya vasculopathy or progressive stenoocclusion, leading to isolated circulation at or above the level of the circle of Willis. Despite this finding, the proportion of patients with ischemic stroke was low (2 of 104; 1.9%). Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) global health scores were lower than population norms by at least 1 standard deviation. Given the overall prevalence of PHACE, it was not possible to obtain the proper power to accurately assess all outcomes. The authors of the study concluded that primary and specialty follow-up care is important for patients with PHACE into adulthood. Further study is needed to identify precise guidelines for long-term follow-up.[

68 ]Table 3. Additional Findings Identified Among the PHACE Syndrome Cohorta Symptom Prevalence Symptom Prevalence ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity syndrome; IH = infantile hemangioma. a Adapted from: Mitchell Braun, Ilona J. Frieden, Dawn H. Siegel, Elizabeth George, Christopher P. Hess, Christine K. Fox, Sarah L. Chamlin, Beth A. Drolet, Denise Metry, Elena Pope, Julie Powell, Kristen Holland, Caden Ulschmid, Marilyn G. Liang, Kelly K. Barry, Tina Ho, Chantal Cotter, Eulalia Baselga, David Bosquez, Surabhi Neerendranath Jain, Jordan K. Bui, Irene Lara-Corrales, Tracy Funk, Alison Small, Wenelia Baghoomian, Albert C. Yan, James R. Treat, Griffin Stockton Hogrogian, Charles Huang, Anita Haggstrom, Mary List, Catherine C. McCuaig, Victoria Barrio, Anthony J. Mancini, Leslie P. Lawley, Kerrie Grunnet-Satcher, Kimberly A. Horii, Brandon Newell, Amy Nopper, Maria C. Garzon, Margaret E. Scollan, Erin F. Mathes, Multicenter Study of Long-Term Outcomes and Quality of Life in PHACE Syndrome after Age 10, The Journal of Pediatrics, Volume 267, 2024, 113907, ISSN 0022-3476, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2024.113907 . This is an open access article distributed under the terms of theCreative Commons CC-BY license, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.b Report of ever having had a seizure. c Including Tourette syndrome ,intention tremors , psychogenicmovement disorder .IH late growth 13/104 (12.5%) Vision difficulty 56/104 (53.8%) Increased color 11/13 (84.6%) Unilateral legal blindness 5/104 (4.8%) Deep growth 2/13 (15.4%) Eye surgeries 26/104 (25%) Increased volume 6/13 (46.2%) Hearing loss 18/104 (17.3%) Additional neurological symptoms Conductive 3/18 (16.7%) Seizuresb 15/104 (14.4%) Sensorineural 3/18 (16.7%) Speech difficulty 36/104 (34.6%) Mixed 6/18 (33.3%) Participated in speech therapy 30/104 (28.8%) Unknown 3/18 (16.7%) Balance problems 28/104 (26.9%) Use of hearing aids 12/104 (11.5%) Difficulty swallowing 11/104 (10.6%) Dental Tic disordersc 6/104 (5.8%) Dental root problem 16/104 (15.4%) Learning diagnosis Defects in enamel 31/104 (29.8%) ADHD 19/104 (18.3%) Dyslexia 10/104 (9.6%)

- An international group of experts published a report of a multicenter study that used cross-sectional interviews and chart review to examine long-term outcomes and quality of life for patients older than 10 years with PHACE syndrome.[

LUMBAR/PELVIS/SACRAL syndrome

Infantile hemangiomas located over the lumbar or sacral spine may be associated with genitourinary, anorectal anomalies, or neurological issues such as tethered cord.[

LUMBAR

- L ower-body hemangiomas and other cutaneous defects.

- U rogenital anomalies or ulceration.

- M yelopathy.

- B ony deformities.

- A norectal malformations or arterial anomalies.

- R enal anomalies.

PELVIS

- P erineal hemangiomas.

- E xternal genital malformations.

- L ipomyelomeningocele.

- V esicorenal abnormalities.

- I mperforate anus.

- S kin tag.

SACRAL

- S pinal dysraphism.

- A nogenital.

- C utaneous.

- R enal and urologic anomalies A ssociated with an angioma of L umbosacral localization.

Segmental lesions over the gluteal cleft and lumbar spine need to be evaluated with either ultrasonography or MRI, depending on the age of the patient. In several studies, ultrasonography evaluations have failed to identify some spinal abnormalities that were later found on MRI evaluation.[

Multiple hemangiomas

Infants with more than five hemangiomas need to be evaluated for visceral hemangiomas. The most common site of involvement is the liver, in which multiple or diffuse lesions can be noted.[

Treatment of infantile hemangioma

The decision to treat patients with hemangiomas is based on several factors, including the following:[

- Size of the lesions.

- Type of hemangioma.

- Location of hemangioma.

- Presence or risk of complications, including ulceration, possibility of scarring or disfigurement, the age of the patient, and the stage of growth of the hemangioma.

This decision is individualized among patients, and it is important to carefully consider the risks and benefits of treatment.

The American Academy of Pediatrics has published clinical practice guidelines on this topic. An early therapeutic intervention was noted to be critical for complex infantile hemangiomas to prevent medical complications and permanent disfigurement. The timing of interventions was noted to be best in the first 1 to 3 months of age. Photos were used to triage low-risk versus high-risk infantile hemangiomas,[

Treatment options for infantile hemangioma include the following:

-

Propranolol therapy . -

Selective and other beta-blocker therapy . -

Corticosteroid therapy . - Laser therapy.

- Usually reserved for ulcerated infantile hemangiomas and residual lesions, such as telangiectasias after the proliferative period.[

83 ] Pulsed dye laser therapy helps with pain from ulcerative infantile hemangiomas. The use of pulsed dye laser therapy as an up-front treatment for infantile hemangiomas is controversial. - A Russian pilot study employed multiline laser equipment using the Nd:YAP Q-Sw/KTP emitters combined with two wavelengths of 1079/540 nm to treat patients with infantile hemangiomas.[

84 ] Laser treatment was performed on 109 patients with 119 hemangiomas. Evaluation of posttreatment samples revealed restoration of normal color, skin relief, and the absence of scars. - A retrospective study in China included 180 patients with superficial hemangiomas who were treated with a 595-nm pulsed dye laser. The study reported that younger children (aged <2 months) received fewer treatments, had shorter courses of disease, and experienced better effects with fewer adverse events when compared with older children.[

85 ]

- Usually reserved for ulcerated infantile hemangiomas and residual lesions, such as telangiectasias after the proliferative period.[

- Excisional surgery. With the advent of new medical treatments, the use of surgery is reserved for ulcerated lesions, residual lesions, large periocular lesions that interfere with vision, and facial lesions with aesthetic impact that do not respond to medical therapy.[

86 ] -

Topical beta-blocker therapy . -

Combined therapy for complicated hemangiomas .

Propranolol therapy

Propranolol, a nonselective beta-blocker, is first-line therapy for infantile hemangiomas. Early studies suggested that propranolol might act through inducing vasoconstriction and/or by decreasing expression of VEGF and bFGF, leading to apoptosis.[

The use of propranolol was first noted in two infants treated for cardiac issues in Europe. A change in color, softening, and decrease in hemangioma size was noted. Since that time, the results of a randomized controlled trial have been reported.[

There are many other published reports about the efficacy and safety of propranolol.[

Evidence (propranolol therapy):

- In a large industry-sponsored randomized trial, 456 infants aged 5 weeks to 5 months with proliferating infantile hemangiomas of at least 1.5 cm received either a placebo or propranolol (1 mg/kg per day or 3 mg/kg per day) for 3 or 6 months. After interim analysis of the first 188 patients who completed 24 weeks of trial treatment, the regimen of 3 mg/kg per day for 6 months was selected for the final efficacy analysis.[

92 ][Level of evidence B3]- Of patients who received the selected regimen, 88% showed improvement by week 5, compared with 5% of patients who received the placebo.

- Adverse events occurred infrequently.

- A retrospective study of 635 infants with infantile hemangiomas who were treated with propranolol (2 mg/kg per day) had the following results:[

97 ][Level of evidence C3]- The overall response rate was 91%, with most patients demonstrating regression.

- Two percent of patients had side effects, none of which were severe.

- A meta-analysis that evaluated 5,130 patients from 61 studies concluded that propranolol was more effective and safer than were other treatments for infantile hemangioma.[

100 ] - Airway infantile hemangioma lesions are rare. A meta-analysis of 61 patients reported the following results:[

101 ]- There was a trend in decreased treatment failure with increased dosing strategies, which is consistent with the use of higher doses of propranolol in these patients (3 mg/kg per day).

- The analysis also suggested that the concurrent use of steroids and propranolol may have reduced efficacy in patients with segmental airway hemangiomas, but prior treatment with steroids had no deleterious effect.

- Additional prospective studies are needed to validate these findings.

- Diffuse (segmental) hemangiomas of the airway are very rare, and their clinical behavior is different from that of isolated airway lesions.

Intralesional administration of propranolol has been used for periorbital lesions in a limited capacity and showed no advantages over oral administration.[

Several expert consensus panel recommendations have been reported, including recommendations from the FDA and the European Medicines Agency after a randomized controlled trial of oral propranolol in infantile hemangioma patients led to FDA approval.[

Considerations for the use of propranolol include the following:[

- Initiation of treatment: Guidance from consensus panels suggested that treatment should be undertaken in consultation with a pediatric vascular anomaly specialist with expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric vascular tumors and in the use of propranolol in children. They suggested that hospitalization for initiation of oral propranolol be considered in the following circumstances:[

103 ]- Infant aged 4 weeks or younger (corrected for gestational age).

- Infant of any age with inadequate social support.

- Infant of any age with comorbid conditions affecting the cardiovascular or respiratory system, including symptomatic airway infantile hemangiomas.

- Infant of any age with conditions affecting blood glucose maintenance.

The pretreatment evaluation (inpatient or outpatient) includes the following:

- History, with focus on cardiovascular and respiratory abnormalities (e.g., poor feeding, dyspnea, tachypnea, diaphoresis, wheezing, heart murmur) and family history of heart block or arrhythmia.

- Physical examination, including cardiac and pulmonary assessment and measurement of heart rate.

- No need for echocardiogram or electrocardiogram for standard-risk patients. Two studies found no contraindication to beta-blocker therapy in 6.5% to 25% of patients who had electrocardiogram abnormalities.[

106 ,107 ] Electrocardiogram should be considered in children with heart rate lower than normal for age and history of arrhythmia or arrhythmia detected during examination. - Family history of congenital heart disease or maternal history of connective tissue disease.

- Dosing: According to the consensus panels, the dosing used is generally 1 mg/kg per day to 3 mg/kg per day divided into two or three doses. The starting dose varies depending on risk factors and location of initiation. Outpatients and inpatients are initially started at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg per day to 1 mg/kg per day and increased over time.[

104 ,105 ,106 ] A retrospective review of initial dosing indicates a starting dose of 2 mg/kg may also be well tolerated. This initial dosing could decrease the need for up-titration and more frequent clinic visits, although prospective studies are needed.[108 ] Initially, dosing of three times per day is recommended for infants younger than 5 weeks and for patients with PHACE syndrome.[47 ,103 ] - Monitoring: Monitoring varies depending on the institution. However, oral propranolol peaks at 1 to 3 hours after administration and most centers measure heart rate and blood pressure 1 and 2 hours after each dose with initiation and then when the dose is increased by at least 0.5 mg/kg per day. Parent and patient education includes when to withhold the medication, signs of hypoglycemia, feeding necessity through the night, and when to call the physician with issues, such as illness, that may interfere with oral intake or lead to dehydration or respiratory problems.

A large retrospective multicenter study assessed the safety of outpatient administration of propranolol and evaluated the need for monitoring. In this study, 783 patients with 1,148 office visits were evaluated. No symptomatic bradycardia or hypotension was noted. Blood pressure evaluation was unreliable. The results suggested that outpatient evaluation may not be necessary for standard-risk patients with infantile hemangiomas.[

109 ] - Contraindications: Propranolol treatment is contraindicated in infants and children with the following:[

103 ,104 ,105 ]- Sinus bradycardia.

- Hypotension.

- Heart block greater than first degree.

- Heart failure.

- Asthma.

- Hypersensitivity.

- PHACE syndrome. PHACE syndrome with CNS arterial disease and/or coarctation of the aorta may be a relative contraindication. A retrospective multi-institutional study that investigated the safety of propranolol therapy for patients with PHACE syndrome identified 76 infants, including 12 patients who were at high risk of having a stroke.[

110 ] The incidence of adverse events in these patients was similar to the incidence in 726 infants who received oral propranolol therapy for hemangioma but did not meet the criteria for PHACE syndrome. A decision to treat should be made in consultation with neurology/neurosurgery and cardiology.

- Adverse effects of propranolol include the following:[

111 ]- Hypoglycemia.

One study in Japan monitored hypoglycemia in infants with infantile hemangiomas who started treatment with propranolol.[

112 ] After treatment with propranolol, the incidences of severe hypoglycemia and hypoglycemic convulsions were approximately 0.54% and 0.35%, respectively. The incidence of hypoglycemic convulsions appeared to be higher in Japan than in Western countries. Severe hypoglycemia was common in infants younger than 1 year when propranolol was used for 6 months or longer. Severe hypoglycemia often developed from 5:00 AM to 9:00 AM, and it was frequently associated with prolonged periods of fasting, poor feeding, or poor physical conditions. - Hypotension.

- Bradycardia.

- Sleep disturbance.

- Diarrhea/constipation.

- Cold extremities.

These complications have been reported in several studies, and severe complications have been rare.[

111 ,113 ] The risk of these complications is increased in patients with comorbidities and concomitant diseases, including diarrhea, vomiting, and respiratory infections. The need for close monitoring and possible periods of drug discontinuation should be considered during periods of illness.A retrospective review of 1,260 children with infantile hemangiomas who were treated with propranolol identified 26 patients (2.1%) with side effects that required discontinuation of propranolol.[

114 ] Severe sleep disturbance was the most common reason for propranolol cessation, accounting for 65.4% of cases. In total, 23 patients received atenolol and 3 patients received prednisolone as second-line therapy. In the multivariate analysis, only younger age (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.201–2.793; P = .009) and lower body weight (95% CI, 1.036–1.972; P = .014) were associated with intolerable side effects. - Hypoglycemia.

- Duration of treatment: There are no consensus guidelines for the treatment duration of propranolol. In a prospective, multi-institutional study that assessed efficacy and safety of propranolol in high-risk patients, the administration of propranolol for a minimum of 6 months, up to a maximum of age 12 months, increased treatment success; dosing of propranolol was 3 mg/kg per day. Treatment results were sustained for up to 3 months after discontinuation of therapy. Efficacy and safety of propranolol in this study were similar to those reported in other studies.[

115 ] - Rebound growth after propranolol therapy: Rebound refers to the growth of infantile hemangiomas after propranolol cessation. A multi-institutional, retrospective review of 997 patients with infantile hemangiomas found a rebound rate of 25.3% in 912 patients with adequate data. On univariate analysis, the factors associated with rebound included discontinuation of treatment before age 9 months, female sex, location on the head or neck, segmental pattern, and deep or mixed skin involvement. On multivariate analysis, only deep infantile hemangiomas and female sex were significantly related.[

116 ] A single-center retrospective review examined 198 patients with infantile hemangioma who underwent oral propranolol therapy. The study reported 35 patients (18%) with rebound growth 1 to 3 months after discontinuation of propranolol treatment. Of the 35 patients, 23 were re-treated with propranolol for up to 3 months. All patients had good responses.[117 ][Level of evidence C3] - Late growth of infantile hemangiomas: Hemangioma growth can occur in patients older than 3 years, and growth as late as age 8.5 years has been reported. Associated risk factors include segmental morphology, large hemangiomas, PHACE syndrome, and deep cutaneous and subcutaneous lesions in the head and neck.[

118 ,119 ]

Selective and other beta-blocker therapy

Because of the nonselective and lipophilic nature of propranolol and its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, other beta-blockers are being used for the treatment of infantile hemangiomas.

Evidence (beta-blocker therapy):

- In two small comparison studies, there was no difference in efficacy between propranolol and atenolol.[

120 ,121 ] - In support of a previous retrospective study, a prospective double-blind study compared nadolol with propranolol in 71 infants (aged 1–6 months).[

122 ][Level of evidence A3]- The study demonstrated noninferiority with respect to efficacy and treatment.

- A prospective study of 76 infants treated with atenolol noted efficacy and safety similar to propranolol.[

123 ][Level of evidence C3]

In one published report, nadolol was associated with the death of an infant (aged 17 weeks) after 10 days of no stool output.[

Additional studies are needed to assess differences between the toxicities of these agents and the toxicities of propranolol.

There is some suggestion that the more selective beta-blockers have fewer side effects.[

Corticosteroid therapy

Before propranolol, corticosteroids were the first line of treatment for infantile hemangiomas. They were first used in the late 1950s but were never approved by the U.S. FDA for this indication. Corticosteroid therapy has become less popular because of the acute and long-term side effects of steroids (gastrointestinal irritability, immunosuppression, adrenocortical suppression, cushingoid features, and growth failure).

Corticosteroids (prednisone or methylprednisolone) are used at times when there is a contraindication to beta-blocker therapy or as initial treatment while a patient is started on beta-blocker therapy.[

Topical beta-blocker therapy

Topical beta-blockers are used mainly for the treatment of small, localized, superficial hemangiomas as an alternative to observation. They have also been used in combination with systemic therapy in complicated hemangiomas or to prevent rebound in hemangiomas being tapered off of systemic treatment.[

The topical timolol that is used is the ophthalmic gel-forming solution 0.5%. One drop is applied to the hemangioma two times per day until stable response is achieved.

This treatment has limited side effects, but infants with a postmenstrual age of younger than 44 weeks and weight at treatment initiation of less than 2,500 grams may be at risk of adverse events, including bradycardia, hypotension, apnea, and hypothermia.[

Evidence (topical timolol therapy):

- A retrospective cohort study included 666 patients with infantile hemangioma who were treated with topical timolol for 12 months.[

133 ]- Of these patients, 583 (87.5%) had visible reductions in the size of their lesions.

- A total of 188 children (28.2%) had excellent responses (no remaining visible abnormality), 127 of whom had complete responses earlier than 12 months.

- Of the remaining patients, 292 (43.8%) had good outcomes (i.e., the hemangioma was less than half its original size), while 103 (15.5%) had fair outcomes (i.e., a visibly smaller hemangioma but not less than half its original size), and 83 (12.5%) had poor outcomes (i.e., there was no change in hemangioma size or it was larger).

- Patients aged 3 months and younger were more likely to have better outcomes than those older than 3 months (P < .001).

- Patients with small infantile hemangiomas (maximum diameter, 1.5–≤5 cm) also had better outcomes than those with large infantile hemangiomas (5–≤10 cm) (P = .046).

- In a multicenter, retrospective, cohort study, 731 children with predominantly superficial hemangiomas were treated with topical timolol 0.5% twice daily.[

129 ]- Ninety-two percent of patients showed significant improvement in hemangioma color.

- Seventy-seven percent of patients showed improvement in hemangioma size, extent, and volume.

- Topical timolol is generally well tolerated; however, data on its safety are limited.

- A Spanish consortium performed a prospective randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of topical timolol for the treatment of infantile hemangioma in the early proliferative stage.[

134 ] This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase IIa pilot clinical trial included patients aged 10 to 60 days with focal or segmental hemangiomas (superficial, deep, mixed, or minimal/arrested growth). Patients were randomly assigned to treatment with either topical timolol maleate solution, 0.5%, or placebo, twice daily for 24 weeks.- At 24 weeks, there were no significant differences between the timolol treatment and the placebo for complete or nearly complete infantile hemangioma resolution (42% for timolol [n = 11] vs. 36% for placebo [n = 11]; P = .37).

Combined therapy for complicated hemangiomas

Combined therapy is considered either at initiation of treatment in complicated lesions in which there is functional impairment or organ compromise or used at the end of systemic therapy to prevent hemangioma rebound. Further investigation of efficacy and safety is needed for these regimens.

Evidence (combined therapy for complicated hemangiomas):

- A prospective randomized study that compared propranolol and 2 weeks of steroid therapy with propranolol alone revealed the following:[

135 ]- Decreased sizes of hemangiomas at 2, 4, and 8 weeks in the combined-therapy group but no statistical difference in the sizes at 6 months.

- A prospective randomized study that compared timolol and propranolol with propranolol alone reported the following:[

136 ]- Decreased color of the infantile hemangiomas in the timolol group but no difference in overall sizes of the infantile hemangiomas between the two treatment groups.

- Other studies have supported this combination.[

137 ,138 ][Level of evidence C3]

Treatment options under clinical evaluation for infantile hemangiomas

Information about National Cancer Institute (NCI)–supported clinical trials can be found on the

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Hemangioma Investigator Group is studying the administration of propranolol for low-risk and standard-risk patients through virtual visits.[

Current Clinical Trials

Use our

Congenital Hemangiomas

Clinical features and diagnostic evaluation

Congenital hemangiomas can be difficult to diagnose, especially for clinicians who are unfamiliar with these lesions. Diagnostic criteria include a purpuric lesion fully formed at birth, frequently with a halo around the lesion, with high flow noted on ultrasound imaging. Essential to the diagnosis is serial observation for decrease or, at least stability, in size over time. These lesions do not enlarge unless there is hemorrhage into the tumor.

Congenital hemangiomas are divided into the following three forms:

- Rapidly involuting congenital hemangiomas (RICH). These lesions are large high-flow lesions that are completely formed at birth but rapidly involute by age 12 to 15 months. They can ulcerate and bleed and can cause transient heart failure and mild coagulopathy. After involution, usually some residual changes in the skin are present (see

Figure 5 ).[140 ,141 ,142 ,143 ]In a retrospective case series of congenital hemangiomas, several high-risk ultrasound findings were noted for RICH. Venous lakes were associated with cardiac failure, and an increased risk of bleeding was noted with venous lakes and venous ectasia. Infants with RICH should be evaluated with ultrasonography and monitored closely if these high-risk features are noted.[

144 ]

Figure 5. Typical appearance of a cutaneous congenital hemangioma at birth. Note the pedunculated mass. This RICH lesion involuted over time but some residual skin changes remained. Credit: Denise Adams, M.D. - Partial involuting congenital hemangiomas (PICH). These lesions are completely formed at birth and involute only partially.[

145 ] - Non-involuting congenital hemangiomas (NICH). These lesions are formed at birth and never involute. Depending on the location of the lesions and whether they cause functional impairment, the lesions may need to be removed surgically.[

146 ,147 ]

Histopathology and molecular features

Congenital hemangiomas are benign vascular tumors that proliferate in utero. Development of these lesions is complete at birth. Histologically, these lesions are GLUT1 negative, unlike infantile hemangiomas. They are usually cutaneous, but can be found in the viscera. Complications include hemorrhage, transient heart failure, and transient coagulopathy.[

Somatic activating variants of GNAQ and GNA11 have been found to be associated with congenital hemangiomas.[

Hepatic Vascular Tumors

With the development of the new WHO and ISSVA classifications, the terminology of pediatric hepatic vascular tumors (HVT) has changed.[

On MRI, vascular tumors of the liver are hyperintense on T2 imaging and hypointense on T1 imaging, with postcontrast imaging demonstrating early peripheral enhancement with eventual diffuse enhancement.[

The differential diagnosis of vascular liver lesions always includes malignant liver tumors. Thus, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) measurements should be included in the initial lab work. AFP is very high in all newborns but will rapidly fall to normal levels in several months. AFP levels should rapidly diminish, but failure to do so or a rising trend of AFP should elicit concern for a hepatoblastoma. There are no prospective studies investigating AFP elevation in patients with hemangiomas.[

Benign hepatic vascular tumors

These lesions are usually divided into the following three categories:[

-

Congenital hemangiomas . -

Infantile hemangiomas . -

Diffuse hepatic infantile hemangiomas .

A more appropriate classification uses an interdisciplinary evaluation, including pathological classification with genomic assessment, radiological imaging evaluation, and clinical history and examination. This is based on the ISSVA and WHO classifications. A study analyzed clinicopathologic characteristics in 33 cases of pediatric hepatic vascular tumors diagnosed between 1970 and 2021.[

Congenital hemangiomas

Focal lesions of the liver are usually congenital hemangiomas (RICH or NICH, rarely PICH) (see

Treatment options for focal vascular lesions of the liver include the following:

- Supportive management. Most lesions are asymptomatic and can be monitored through involution using ultrasonography.

- Embolization. This procedure is considered for severe symptomatic shunting that is unresponsive to treatment for congestive heart failure. These procedures need to be performed by interventional radiologists with expertise in vascular anomalies.[

159 ] - Surgery. Patients with massive focal symptomatic hepatic congenital hemangioma unresponsive to supportive management or radiological intervention may be candidates for surgical resection. This is a rare circumstance and needs to be evaluated by an interdisciplinary vascular anomaly team. Indication for surgical removal includes rupture, bleeding, and nonresolving coagulopathy. Two patients were reported to require surgical resection after the development of clinically significant ascites as their RICH involuted.[

160 ,161 ]

No medication has proven to be an effective treatment for these lesions, and infants need to be supported during the initial period until involution begins.[

Figure 6. Single liver lesion (intrahepatic congenital hemangioma). MRI image of a congenital hemangioma. Note the central enhancement, which is typical for an intrahepatic congenital hemangioma. Credit: Denise Adams, M.D.

Infantile hemangiomas

Multifocal hepatic lesions are infantile hemangiomas. Multifocal lesions may not need to be treated if the patient is asymptomatic. These lesions typically follow the same proliferative and involution course as cutaneous hemangiomas.[

Diffuse hepatic infantile hemangiomas

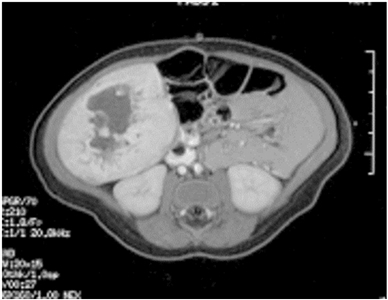

Diffuse liver lesions are very serious (see

Figure 7. Diffuse liver lesions with classical imaging on CT. Note the peripheral enhancement in early contrast phase. Credit: Denise Adams, M.D.

Treatment options for diffuse liver lesions may include the following:

- Propranolol: Beta-blockers are the most common treatment for diffuse and some multifocal infantile hemangiomas of the liver. Treatment doses of 2 to 3 mg/kg per day are indicated.[

92 ] - Thyroid hormone replacement: Thyroid hormone replacement therapy must be aggressive if hypothyroidism is diagnosed. Treatment with higher doses of hormones may be needed because the deficiency is caused by the aggressive consumption of the hormone by the tumor.[

78 ] - Chemotherapy: Steroids, cyclophosphamide, and vincristine have been used to treat diffuse liver infantile hemangioma.[

76 ,165 ,166 ] - Liver transplant: If a patient does not respond to medical management, a transplant may be indicated.[

167 ] Transplant is considered only for patients with severe diffuse lesions who have multisystem organ failure and there is insufficient time for effective pharmacologic therapy.

Malignant hepatic vascular tumors

There have been isolated reports of malignancy in patients with diffuse hepatic infantile hemangiomas.[

Hepatic angiosarcoma

Hepatic angiosarcoma (HA) in children is extremely rare, and there are approximately 80 cases reported in the medical literature. There is a female predilection, and the median age at diagnosis is 40 months. Hepatic angiosarcomas present rapidly and are diagnosed by histopathology (see

Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma

Hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma is a very rare tumor in the liver, especially in children. There is also a female predilection, and it occurs most frequently in young adults. This tumor may often involve extrahepatic disease, reportedly in over one-third of patients. It presents similarly to other hepatic tumors, with hepatomegaly and abdominal pain. However, hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma behaves more moderately than hepatic angiosarcoma, and patients with hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma have better outcomes.

Imaging is very helpful in diagnosing hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma. In addition to a hypoechoic lesion on ultrasonography, ultrasonography with contrast or MRI with contrast show a typical target sign, due to concentric filling of the tumor. This is thought to be due to concentric areas of necrosis and alternating areas of dense, active tumor cells. In addition, hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma is known for avid glucose uptake. The use of fluorine F 18-fludeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET), with computed tomography (CT) or MRI (PET-CT/PET-MRI), is helpful in confirming the diagnosis and determining organ involvement since these tumors often have extrahepatic disease. This imaging modality is also helpful in monitoring patients for disease recurrence after intervention. Ultimately, histopathological diagnosis is the preferred method, and these tumors exhibit both epithelioid and histiocytic/dendritic cells and a characteristic immunohistochemistry pattern in tumor samples (see

Treatment of hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma is primarily surgical resection, either hepatectomy or liver transplant. Interventional procedures can also be used. Studies are evaluating whether incorporating chemotherapy into the treatment plan improves outcomes.[

| Features | Hepatic Congenital Hemangioma (HCH) | Hepatic Infantile Hemangioma (HIH) | Hepatic Angiosarcoma (HA) | Hepatic Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma (HEHE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHF = congestive heart failure; NICH = noninvoluting congenital hemangioma; PICH = partially involuting congenital hemangioma; RICH = rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma. | ||||

| a Adapted from Berklite et al.[ |

||||

| Clinical Presentation | Noted at birth or prenatally; CHF; transient coagulopathy; single lesions; RICH, PICH, rarely NICH | Noted postnatally, usually associated with skin lesions; diffuse lesions with significant hypothyroidism and CHF | Rare in pediatrics, has been seen in neonates and toddlers; very aggressive | Very rare; associated with other lesions (bone, lung); variable course |

| Imaging | Solid lesion | Multiple or diffuse lesions | Large infiltrative, can be multiple or diffuse, can be seen with IH, or rarely transformation can occur to HA | Solid or multiple lesions |

| Histology | Involutional changes (calcification, necrosis), dilated, fibrotic stroma capillary vessels | Anastomosing sinusoidal vasculature, dense normal appearing endothelial cells | Marked cytological atypia, infiltrative, epithelioid to spindle tumor cells, marked mitotic activity | Epithelioid endothelial cells in a background of myxohyaline stroma |

| GLUT1 | Negative | Positive | Positive in 20% of tumors | Negative |

| Somatic Variants or Gene Fusions | GNAQ,GNA11 | None | KRAS,KDR,PTPRB,FLT4,PLCG1,PIK3CA,TP53,TIE1,AKT1,CIC | YAP1::TFE3,WWTR1::CAMTA1 |

Spindle Cell Hemangioma

Clinical presentation, molecular features, and histopathology

Spindle cell hemangiomas, initially called spindle cell hemangioendotheliomas, often occur as superficial (skin and subcutis), painful lesions involving distal extremities in children and adults.[

Spindle cell hemangiomas can be seen in patients with Maffucci syndrome (cutaneous spindle cell hemangiomas occurring with cartilaginous tumors, enchondromas) and Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome (capillary/lymphatic/venous malformations), generalized lymphatic anomalies, lymphedema, and organized thrombus.[

Treatment of spindle cell hemangioma

There is no standard treatment for spindle cell hemangioma because it has not been studied in clinical trials. Surgical removal is usually curative, although there is a risk of recurrence.[

Epithelioid Hemangioma

Clinical presentation and histopathology

Epithelioid hemangiomas (EH) are benign lesions that usually occur in the skin and subcutis but can occur in other areas such as the bone, with focal and multifocal lesions.[

On pathological evaluation, epithelioid hemangiomas have small caliber capillaries with eosinophilic, vacuolated cytoplasm and large oval, grooved, and lobulated nuclei. The endothelial cells are plump and are mature, well-formed vessels surrounded by multiple epithelioid endothelial cells within abundant cytoplasm. They lack cellular atypia and mitotic activity.[

In a study of 58 cases of epithelioid hemangiomas, 29% were found to have FOS gene rearrangements. FOS gene rearrangements were noted more often in cellular epithelioid hemangiomas and intraosseous lesions compared with lesions in the skin, soft tissue, and head and neck. This genetic abnormality can be helpful in distinguishing epithelioid hemangiomas from other malignant epithelioid vascular tumors.[

A single-institution report reviewed 11 patients with epithelioid hemangiomas (median age, 14.4 years) who were diagnosed between 1999 and 2017. Lesions occurred in the lower extremities (five patients), skull (three patients), pelvis (two patients), and spine (one patient). Five patients had multifocal disease. Patients presented with localized pain and neurological symptoms, including cranial nerve injury. No significant cytological atypia was noted, and the endothelial cells were positive for CD31 and ERG, and negative for cytokeratin and CAMPTA1. Median follow-up was 1.5 years. Various modalities of treatments were used, including surgery, endovascular embolization, cryoablation, and medical management. One patient received sirolimus, and another patient received interferon; the lesions of both patients shrank within the first year of follow-up. The youngest patient, aged 2.5 years, had multifocal skull lesions that partially regressed 1 year later without treatment.[

Treatment of epithelioid hemangioma

There is no standard treatment for epithelioid hemangioma because it has not been studied in clinical trials. Treatment usually consists of curettage, sclerotherapy, or resection. In rare cases, radiation therapy may be used.[

Pyogenic Granuloma (Lobular Capillary Hemangioma)

Clinical presentation, histopathology, and molecular features

Pyogenic granulomas (PG), known as lobular capillary hemangiomas, are benign reactive lesions. Pyogenic granulomas can present at any age—including at birth (congenitally), during the neonatal period, during infancy, or during pregnancy—although they are most common in older children and young adults. These lesions can arise spontaneously, in sites of trauma, or within capillary and arteriovenous malformations. Pyogenic granulomas have also been associated with medications including oral contraceptives and retinoids.

Pyogenic granulomas occur as solitary growths, but multiple (grouped) or rarely disseminated lesions have been described.[

The pathogenesis of pyogenic granulomas associated with capillary malformations and those that are sporadic are unknown. A study investigated ten patients with pyogenic granulomas arising from a capillary malformation and found eight with BRAF c.1799T>A variants, one with an NRAS c.182A>G variant, and one with a GNAQ c.548G>A variant. This GNAQ variant was also found in the underlying capillary malformation. In 25 patients with pyogenic granulomas and no capillary malformation, 3 patients had BRAF c.1799T>A variants and 1 patient had a KRAS c.37G>C variant. These genetic findings will help with future treatment modalities for this benign vascular tumor.[

Treatment of pyogenic granuloma

Full-thickness excision is the treatment with the lowest recurrence rate (around 3%),[

Evidence (topical beta-blockers):

- In a single-arm series of patients with acquired ocular pyogenic granulomas, a small number of pediatric patients were treated for 21 days to 6 weeks with twice-daily topical timolol, 0.5%.[

187 ,188 ][Level of evidence C3]- Complete or near-complete responses without subsequent recurrence or progression were noted in 75% to 100% of the patients (all ages).

- A study of 22 patients with cutaneous pyogenic granulomas who were treated with topical 1% propranolol ointment with occlusion had the following results:[

189 ]- Fifty-nine percent of patients achieved complete responses (mean, 66 days), 18% of patients had stable disease, and 22% of patients did not respond to the treatment.

- In this study, only skin toxicity was assessed.

- The authors did not comment on the penetrance of the propranolol formulation or include a safety evaluation of the side effects such as hypoglycemia and the effects on heart rate or blood pressure.

Angiofibroma

Clinical presentation

Angiofibromas are rare, benign neoplasms in the pediatric population. Typically, they are cutaneous lesions associated with tuberous sclerosis, appearing as red papules on the face.

Treatment of angiofibroma

Excision of the tumor, laser treatments, and topical treatments, such as sirolimus, have been used.[

Evidence (topical sirolimus):

- A prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of nine cancer centers that included 62 patients who received sirolimus gel demonstrated the following results:[

193 ]- Sixty percent of patients who received sirolimus showed significant improvement in the size and color of the lesion, which was assessed at week 12.

- In another prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study that included six monthly clinic visits, 179 patients with tuberous sclerosis complex–related facial angiofibromas were treated with topical rapamycin (sirolimus) 0.3 g per 30 g (1%).[

194 ]- According to the Angiofibroma Grading Scale, patients who were treated with topical rapamycin showed a statistically and clinically significant improvement in facial angiofibromas.

Juvenile Nasopharyngeal Angiofibroma

Clinical presentation and histopathology

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas (JNA) account for 0.5% of all head and neck tumors.[

Despite their benign-appearing histology, juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas can be locally destructive, spreading from the nasal cavity to the nasopharynx, paranasal sinuses, and orbit skull base, with intracranial extension. Some publications have suggested a hormonal influence on juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas, with emphasis on the molecular mechanisms involved.[

Treatment of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma

Surgical excision is the treatment of choice, but this can be challenging because of the extent of the lesion. A single-institution retrospective review of juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas identified 37 patients with lateral extension.[

Juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibromas have also been treated with radiation therapy, chemotherapy, alpha-interferon therapy, and sirolimus.[

References:

- Kilcline C, Frieden IJ: Infantile hemangiomas: how common are they? A systematic review of the medical literature. Pediatr Dermatol 25 (2): 168-73, 2008 Mar-Apr.

- Munden A, Butschek R, Tom WL, et al.: Prospective study of infantile haemangiomas: incidence, clinical characteristics and association with placental anomalies. Br J Dermatol 170 (4): 907-13, 2014.