Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage

Plans through your employer

Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

Learn

Living or working abroad?

Ewing Sarcoma and Undifferentiated Small Round Cell Sarcomas of Bone and Soft Tissue Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

General Information About Ewing Sarcoma and Undifferentiated Small Round Cell Sarcomas of Bone and Soft Tissue

Dramatic improvements in survival have been achieved for children and adolescents with cancer.[

Studies using immunohistochemical markers,[

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors of soft tissue and bone was modified in 2020 to introduce a new chapter on undifferentiated small round cell sarcomas of bone and soft tissue. This WHO chapter consists of Ewing sarcoma and three main categories, including round cell sarcomas with EWSR1::non-ETS fusions, CIC-rearranged sarcoma, and sarcomas with BCOR genetic alterations.[

Before the widespread availability of genomic testing, Ewing sarcoma was identified by the appearance of small, round, blue cells on light microscopic examination, along with positive staining for CD99 by immunohistochemistry. The identification of the recurring t(11;22) translocation in most Ewing sarcoma tumors led to the discovery that most tumors classified as Ewing sarcoma had a translocation that juxtaposed a portion of the EWSR1 gene to a portion of a gene in the ETS family, resulting in a transforming transcript. Not all undifferentiated small round cell sarcomas of bone and soft tissue have such a translocation. Further research identified additional genetic changes, including tumors with translocations of the CIC gene or the BCOR gene. These groups of tumors occur much less frequently than Ewing sarcoma, and data on these patients are based on smaller sample sizes and less homogeneous treatment; therefore, patient outcomes are harder to quantify with precision. Most of these tumors have been treated with regimens designed for Ewing sarcoma, and the consensus was that they were often included in clinical trials for the treatment of Ewing sarcoma, sometimes referred to as translocation-negative Ewing sarcoma. It is now agreed that these tumors are sufficiently different from Ewing sarcoma and that they should be stratified and analyzed separately from Ewing sarcoma, even if they are treated with similar therapy. In this summary, these tumors are described separately. For more information about these smaller groups of tumors, see the following sections:

-

Undifferentiated Small Round Cell Sarcomas With BCOR Genetic Alterations . -

Undifferentiated Small Round Cell Sarcomas With CIC Genetic Alterations . -

Undifferentiated Small Round Cell Sarcomas With EWSR1::non-ETS Fusions .

Incidence

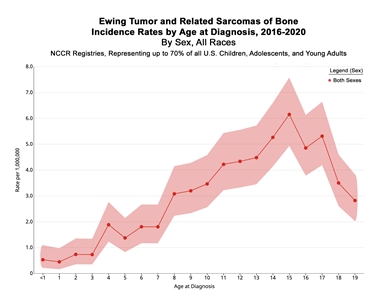

In the United States between 2016 and 2020, the National Childhood Cancer Registry (NCCR) reported an incidence rate of Ewing sarcoma and related sarcomas of bone of 3.0 cases per 1 million in children and adolescents younger than 20 years.[

| Age (years) | Rate per 1,000,000 | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| a Source: National Childhood Cancer Registry (NCCR) Explorer.[ |

||

| <1 | 0.5 | 0.2–1.1 |

| 1–4 | 1 | 0.7–1.3 |

| 5–9 | 2.3 | 1.9–2.6 |

| 10–14 | 4.3 | 3.9–4.9 |

| 15–19 | 4.5 | 4.0–5.0 |

Figure 1. Incidence rates of Ewing tumor and related sarcomas of bone by age at diagnosis in the National Childhood Cancer Registry (NCCR) from 2016 to 2020. Credit: NCCR*Explorer: An interactive website for NCCR cancer statistics [Internet]. National Cancer Institute; 2023 Sep 7. [updated: 2023 Sep 8; cited 2024 Sep 4]. Available from: https://nccrexplorer.ccdi.cancer.gov.

The incidence of Ewing sarcoma in the United States is nine times greater in White people than in Black people, with an intermediate incidence in Asian people.[

Based on data from 1,426 patients entered on European Intergroup Cooperative Ewing Sarcoma Studies, 59% of patients are male and 41% are female.[

Genetic Predisposition to Ewing Sarcoma

Conventional understanding of translocation-driven sarcoma such as Ewing sarcoma suggests that these patients do not have a genetic predisposition.[

Genome-wide association studies have identified susceptibility loci for Ewing sarcoma at 1p36.22, 10q21, and 15q15.[

Clinical Presentation

Clinical presentation of Ewing sarcoma varies and depends on the tumor's size and location.

Primary sites of bone disease are listed in

| Primary Site | Incidence Rate |

|---|---|

| Skull | 5% |

| Spine | 7% |

| Rib | 11% |

| Sternum, scapula, and clavicle | 5% |

| Humerus | 7% |

| Radius, ulna, hand | 2% |

| Pelvis | 18% |

| Femur | 11% |

| Tibia, fibula, patella, foot | 14% |

| Soft tissue | 19% |

The time from the first symptom to diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma is often long, with a median interval reported from 2 to 5 months. Longer times are associated with older age and pelvic primary sites. Time from the first symptom to diagnosis has not been associated with metastasis, surgical outcome, or survival.[

Approximately 25% of patients with Ewing sarcoma have metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis, with lung, bone, and bone marrow being the most common metastatic sites.[

A retrospective analysis examined patients treated on two Children's Oncology Group (COG) studies, INT-0154 and AEWS0031 (NCT00006734). This study compared the clinical characteristics of 213 patients with extraskeletal primary Ewing sarcoma with those of 826 patients with primary Ewing sarcoma of bone.[

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database was used to compare patients younger than 40 years with Ewing sarcoma who presented with skeletal and extraosseous primary sites (see

| Characteristic | Extraosseous Ewing Sarcoma | Skeletal Ewing Sarcoma | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| a Adapted from Applebaum et al.[ |

|||

| Mean age (range), years | 20 (0–39) | 16 (0–39) | <.001 |

| Male | 53% | 63% | <.001 |

| White race | 85% | 93% | <.001 |

| Axial primary sites | 73% | 54% | <.001 |

| Pelvic primary sites | 20% | 27% | .001 |

Diagnostic Evaluation

The following tests and procedures may be used to diagnose or stage Ewing sarcoma:

- Physical examination and history.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of primary tumor site.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan of chest.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) scan.

- Bone scan. Bone scan was traditionally routinely performed on all patients with Ewing sarcoma for staging. However, many investigators believe that the PET scan can replace the bone scan.[

25 ,26 ] - Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy.

- X-ray of primary bone sites.

- Complete blood count.

- Blood chemistry studies, such as lactate dehydrogenase (LDH).

Skip metastasis evaluation is important for primary appendicular bone tumors. Thus, imaging of the entire involved bone is standardly performed. In one retrospective study, skip metastasis was seen in 15.8% of patients. The presence of skip metastasis was associated with an increased risk of distant metastatic disease.[

Omission of bone marrow biopsy and aspiration may be considered, when fluorine F 18-fludeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) PET imaging is used, in patients with otherwise localized disease after initial staging studies. A systematic review of Ewing sarcoma studies was performed to assess the incidence of bone marrow metastasis and the role of 18F-FDG PET imaging to detect bone marrow metastasis.[

Prognostic Factors

The two major types of prognostic factors for patients with Ewing sarcoma are grouped as follows:

-

Pretreatment factors . -

Response to initial therapy factors .

Pretreatment factors

- Metastases: The presence or absence of metastatic disease is the single most powerful predictor of outcome. Any metastatic disease defined by standard imaging techniques or bone marrow aspirate/biopsy by morphology is an adverse prognostic factor. Metastases at diagnosis are detected in about 25% of patients.[

11 ]Patients with metastatic disease confined to the lung have a better prognosis than patients with extrapulmonary metastatic sites.[

29 ,30 ,31 ,32 ] The number of pulmonary lesions does not seem to correlate with outcome, but patients with unilateral lung involvement have a better prognosis than patients with bilateral lung involvement.[33 ]Patients with metastasis to only bone seem to have a better outcome than patients with metastases to both bone and lung.[

34 ,35 ]Based on an analysis from the SEER database, regional lymph node involvement in patients is associated with an inferior overall outcome when compared with patients without regional lymph node involvement.[

36 ] - Site of tumor: Patients with Ewing sarcoma in the distal extremities have more favorable outcomes. Patients with Ewing sarcoma in the proximal extremities have an intermediate prognosis, followed by patients with central or pelvic sites.[

29 ,31 ,32 ,37 ] However, a trial from the COG showed similar outcomes for patients with pelvic primary tumors compared with other sites.[21 ]One study retrospectively analyzed a single-institution's experience with visceral Ewing sarcoma. The study focused on surgical management and compared the outcomes of patients with visceral Ewing sarcoma with those of patients with osseous and soft tissue Ewing sarcoma.[

38 ] There were 156 patients with Ewing sarcoma identified: 117 osseous Ewing sarcomas, 20 soft tissue Ewing sarcomas, and 19 visceral Ewing sarcomas. Visceral Ewing sarcomas arose in the kidneys (n = 5), lungs (n = 5), intestines (n = 2), esophagus (n = 1), liver (n = 1), pancreas (n = 1), adrenal gland (n = 1), vagina (n = 1), brain (n = 1), and spinal cord (n = 1). Visceral Ewing sarcoma was more frequently metastatic at presentation (63.2%; P = .005). However, there was no significant difference in overall survival (OS) or relapse-free survival among the Ewing sarcoma groups, with similar follow-up intervals. - Extraskeletal versus skeletal primary tumors: The COG performed a retrospective analysis from two large cooperative trials that used similar treatment regimens.[

23 ] They identified 213 patients with extraskeletal primary tumors and 826 patients with skeletal primary tumors. Patients with extraskeletal primary tumors were more likely to have an axial primary site, less likely to have large primary tumors, and had a statistically significant better prognosis than did patients with skeletal primary tumors. - Tumor size or volume: Most studies have shown that tumor size or volume is an important prognostic factor. Cutoffs of a volume of 100 mL or 200 mL and/or single dimension greater than 8 cm are used to define larger tumors. Larger tumors tend to occur in unfavorable sites.[

31 ,32 ,39 ] - Age: Younger patients generally have a better prognosis than older patients, as noted in the following studies:[

13 ,29 ,32 ,37 ,40 ,41 ,42 ]- In North American studies, patients younger than 10 years had a better outcome than those aged 10 to 17 years at diagnosis (relative risk [RR], 1.4). Patients older than 18 years had an inferior outcome (RR, 2.5).[

43 ,44 ,45 ] - A retrospective review of two consecutive German trials for Ewing sarcoma identified 47 patients older than 40 years.[

46 ] With adequate multimodal therapy, survival was comparable to the survival observed in adolescents treated on the same trials. - Review of the SEER database from 1973 to 2011 identified 1,957 patients with Ewing sarcoma.[

47 ] Thirty-nine of these patients (2.0%) were younger than 12 months at diagnosis. Infants were less likely to receive radiation therapy and more likely to have soft tissue primary sites. Early death was more common in infants, but the OS did not differ significantly from that of older patients. - A European retrospective review identified 2,635 patients with Ewing sarcoma of bone.[

48 ] Sites of primary and metastatic tumors differed according to the age groups of young children (0–9 years), early adolescence (10–14 years), late adolescence (15–19 years), young adults (20–24 years), and adults (older than 24 years). Young children had the most striking differences in site of disease, with a lower proportion of pelvic primary and axial tumors. Young children also presented less often with metastatic disease at diagnosis.

- In North American studies, patients younger than 10 years had a better outcome than those aged 10 to 17 years at diagnosis (relative risk [RR], 1.4). Patients older than 18 years had an inferior outcome (RR, 2.5).[

- Sex: Females with Ewing sarcoma have a better prognosis than males with Ewing sarcoma.[

14 ,32 ,37 ] - Serum LDH: Increased serum LDH levels before treatment are associated with inferior prognosis. Increased LDH levels are also associated with large primary tumors and metastatic disease.[

37 ] - Pathological fracture: A single-institution retrospective analysis of 78 patients with Ewing sarcoma suggested that pathological fracture at initial presentation was associated with inferior event-free survival (EFS) and OS.[

49 ][Level of evidence C1] Another study found that pathological fracture at the time of diagnosis did not preclude surgical resection and was not associated with an adverse outcome.[50 ] - Previous treatment for cancer: In the SEER database, 58 patients with Ewing sarcoma were diagnosed after treatment for a previous malignancy (2.1% of patients with Ewing sarcoma). These patients were compared with 2,756 patients with Ewing sarcoma as a first cancer over the same period. Patients with Ewing sarcoma as a second malignant neoplasm were older (secondary Ewing sarcoma, mean age of 47.8 years; primary Ewing sarcoma, mean age of 22.5 years), more likely to have a primary tumor in an axial or extraskeletal site, and had a worse prognosis (5-year OS rates of 43.5% for patients with secondary Ewing sarcoma and 64.2% for patients with primary Ewing sarcoma).[

51 ] - Chromosomal alterations:

- Complex karyotype (defined as the presence of five or more independent chromosome abnormalities at diagnosis) and modal chromosome numbers lower than 50 appear to have adverse prognostic significance.[

52 ] - Gain of chromosome 1q and/or deletion of chromosome 16q has been associated with inferior prognosis for patients with Ewing sarcoma in several cohorts.[

53 ,54 ,55 ] These two chromosomal alterations commonly occur together across a range of cancer types, including Ewing sarcoma.[56 ] Their co-occurrence is likely a result of their derivation from an unbalanced t(1;16) translocation resulting in gain of chromosome 1q together with loss of chromosomal material from 16q.[57 ,58 ]

- Complex karyotype (defined as the presence of five or more independent chromosome abnormalities at diagnosis) and modal chromosome numbers lower than 50 appear to have adverse prognostic significance.[

- Detectable Ewing sarcoma cells, fusion transcripts, or circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in peripheral blood: Several techniques to evaluate the presence of Ewing sarcoma in the peripheral blood have been proposed. Flow cytometry for cells that express the CD99 antigen was not sufficiently sensitive to serve as a reliable biomarker.[

59 ,60 ] Reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for the EWSR1::FLI1 translocation was also not considered a reliable biomarker.[61 ]A more sensitive technique used patient-specific primers designed after identification of the specific translocation breakpoint in combination with droplet digital PCR to detect the EWSR1 fusion. This technique reported a sensitivity threshold of 0.009% to 0.018%.[

62 ] Levels of circulating cell-free DNA were higher in patients with metastatic disease than in patients with localized disease.A next-generation sequencing hybrid capture assay and an ultra-low-pass whole-genome sequencing assay were used to detect the EWSR1 fusion in ctDNA in banked plasma from patients with Ewing sarcoma. Among patients with newly diagnosed localized Ewing sarcoma, detectable ctDNA was associated with inferior 3-year EFS rates (48.6% vs. 82.1%; P = .006) and OS rates (79.8% vs. 92.6%; P = .01).[

63 ]ctDNA was separately assayed by digital-droplet PCR in 102 patients who were treated in the EWING2008 (NCT00987636) trial.[

64 ] Pretreatment ctDNA copy numbers correlated with EFS and OS. A reduction in ctDNA levels below the detection limit was observed in most patients after only two blocks of vincristine, ifosfamide, doxorubicin, and etoposide (VIDE) induction chemotherapy. The persistence of ctDNA after two blocks of VIDE was a strong predictor of poor outcomes. - Detectable fusion transcripts in morphologically normal marrow: RT-PCR can be used to detect fusion transcripts in bone marrow. In a single retrospective study using patients with normal marrow morphology and no other metastatic site, fusion transcript detection in marrow or peripheral blood was associated with an increased risk of relapse.[

60 ] However, a larger cohort (n = 225) of patients with localized Ewing sarcoma did not show a difference in EFS or OS based on the detection of fusion transcripts in blood or bone marrow.[65 ] - Gene alterations: A prospective analysis of TP53 variants and/or CDKN2A deletions was done in patients with Ewing sarcoma enrolled on COG clinical trials. The analysis found no association of these alterations with EFS.[

66 ]In a study of 299 patients with Ewing sarcoma, 41 patients (14%) had STAG2 variants and 16 patients (5%) had TP53 variants.[

55 ] There was no association with OS for patients with either the STAG2 or TP53 variant alone. However, the nine patients (3%) with tumors that had both STAG2 and TP53 variants had a significantly decreased OS rate (<20% at 4 years).The COG analyzed STAG2 expression by immunohistochemistry in children with Ewing sarcoma who participated in frontline treatment trials.[

67 ] STAG2 was lost in 29 of 108 patients with localized disease and in 6 of 27 patients with metastatic disease. Among patients who had immunohistochemistry and sequencing performed, no cases (0 of 17) with STAG2 expression had STAG2 variants, and 2 of 7 cases with STAG2 loss had STAG2 variants. Among patients with localized disease, the 5-year EFS rate was 54% (95% CI, 34%–70%) for those with STAG2 loss, compared with 75% (95% CI, 63%–84%) for those with STAG2 expression (P = .0034).

The following are not considered to be adverse prognostic factors for Ewing sarcoma:

- Histopathology: The degree of neural differentiation is not a prognostic factor in Ewing sarcoma.[

68 ,69 ] - Fusion subtype: The EWSR1::ETS translocation associated with Ewing sarcoma can occur at several potential breakpoints in each of the genes that join to form the novel segment of DNA. Once thought to be significant,[

70 ] two large series have shown that the EWSR1::ETS translocation breakpoint site is not an adverse prognostic factor.[71 ,72 ]

Response to initial therapy factors

Multiple studies have shown that patients with minimal or no residual viable tumor after presurgical chemotherapy have a significantly better EFS than do patients with larger amounts of viable tumor.[

Patients with poor response to presurgical chemotherapy have an increased risk of local recurrence.[

A retrospective analysis of risk factors for recurrence was performed in patients who received initial chemotherapy and underwent surgical resection of the primary tumor.[

- Adverse risk factors for local recurrence were pelvic primary tumors (hazard ratio [HR], 2.04; 95% CI, 1.10–3.80) and marginal/intralesional resection (HR, 2.28; 95% CI, 1.25–4.16). The addition of radiation therapy was associated with improved outcome (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.28–0.95).

- Adverse risk factors for developing new pulmonary metastasis were less than 90% necrosis (HR, 2.13; 95% CI, 1.13–4.00) and previous pulmonary metastasis (HR, 4.90; 95% CI, 2.28–8.52).

- Adverse risk factors for death included pulmonary metastasis (HR, 8.08; 95% CI, 4.01–16.29), bone or other metastasis (HR, 10.23; 95% CI, 4.90–21.36), and less than 90% necrosis (HR, 6.35; 95% CI, 3.18–12.69).

- Early local recurrence (0–24 months) negatively influenced survival (HR, 3.79; 95% CI, 1.34–10.76).

In a retrospective cohort of 148 patients with pulmonary metastatic Ewing sarcoma, 41.2% had radiographic resolution of lung nodules after initial induction chemotherapy.[

References:

- Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC, et al.: Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer 120 (16): 2497-506, 2014.

- National Cancer Institute: NCCR*Explorer: An interactive website for NCCR cancer statistics. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Available online . Last accessed August 23, 2024. - Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute: SEER*Explorer: An interactive website for SEER cancer statistics. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute.

Available online . Last accessed September 5, 2024. - Olsen SH, Thomas DG, Lucas DR: Cluster analysis of immunohistochemical profiles in synovial sarcoma, malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, and Ewing sarcoma. Mod Pathol 19 (5): 659-68, 2006.

- Delattre O, Zucman J, Melot T, et al.: The Ewing family of tumors--a subgroup of small-round-cell tumors defined by specific chimeric transcripts. N Engl J Med 331 (5): 294-9, 1994.

- Dagher R, Pham TA, Sorbara L, et al.: Molecular confirmation of Ewing sarcoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 23 (4): 221-4, 2001.

- Llombart-Bosch A, Carda C, Peydro-Olaya A, et al.: Soft tissue Ewing's sarcoma. Characterization in established cultures and xenografts with evidence of a neuroectodermic phenotype. Cancer 66 (12): 2589-601, 1990.

- Suvà ML, Riggi N, Stehle JC, et al.: Identification of cancer stem cells in Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer Res 69 (5): 1776-81, 2009.

- Tirode F, Laud-Duval K, Prieur A, et al.: Mesenchymal stem cell features of Ewing tumors. Cancer Cell 11 (5): 421-9, 2007.

- Choi JH, Ro JY: The 2020 WHO Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissue: Selected Changes and New Entities. Adv Anat Pathol 28 (1): 44-58, 2021.

- Esiashvili N, Goodman M, Marcus RB: Changes in incidence and survival of Ewing sarcoma patients over the past 3 decades: Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results data. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 30 (6): 425-30, 2008.

- Kim SY, Tsokos M, Helman LJ: Dilemmas associated with congenital ewing sarcoma family tumors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 30 (1): 4-7, 2008.

- van den Berg H, Dirksen U, Ranft A, et al.: Ewing tumors in infants. Pediatr Blood Cancer 50 (4): 761-4, 2008.

- Jawad MU, Cheung MC, Min ES, et al.: Ewing sarcoma demonstrates racial disparities in incidence-related and sex-related differences in outcome: an analysis of 1631 cases from the SEER database, 1973-2005. Cancer 115 (15): 3526-36, 2009.

- Beck R, Monument MJ, Watkins WS, et al.: EWS/FLI-responsive GGAA microsatellites exhibit polymorphic differences between European and African populations. Cancer Genet 205 (6): 304-12, 2012.

- Grünewald TG, Bernard V, Gilardi-Hebenstreit P, et al.: Chimeric EWSR1-FLI1 regulates the Ewing sarcoma susceptibility gene EGR2 via a GGAA microsatellite. Nat Genet 47 (9): 1073-8, 2015.

- Paulussen M, Craft AW, Lewis I, et al.: Results of the EICESS-92 Study: two randomized trials of Ewing's sarcoma treatment--cyclophosphamide compared with ifosfamide in standard-risk patients and assessment of benefit of etoposide added to standard treatment in high-risk patients. J Clin Oncol 26 (27): 4385-93, 2008.

- Gillani R, Camp SY, Han S, et al.: Germline predisposition to pediatric Ewing sarcoma is characterized by inherited pathogenic variants in DNA damage repair genes. Am J Hum Genet 109 (6): 1026-1037, 2022.

- Postel-Vinay S, Véron AS, Tirode F, et al.: Common variants near TARDBP and EGR2 are associated with susceptibility to Ewing sarcoma. Nat Genet 44 (3): 323-7, 2012.

- Machiela MJ, Grünewald TGP, Surdez D, et al.: Genome-wide association study identifies multiple new loci associated with Ewing sarcoma susceptibility. Nat Commun 9 (1): 3184, 2018.

- Leavey PJ, Laack NN, Krailo MD, et al.: Phase III Trial Adding Vincristine-Topotecan-Cyclophosphamide to the Initial Treatment of Patients With Nonmetastatic Ewing Sarcoma: A Children's Oncology Group Report. J Clin Oncol 39 (36): 4029-4038, 2021.

- Brasme JF, Chalumeau M, Oberlin O, et al.: Time to diagnosis of Ewing tumors in children and adolescents is not associated with metastasis or survival: a prospective multicenter study of 436 patients. J Clin Oncol 32 (18): 1935-40, 2014.

- Cash T, McIlvaine E, Krailo MD, et al.: Comparison of clinical features and outcomes in patients with extraskeletal versus skeletal localized Ewing sarcoma: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63 (10): 1771-9, 2016.

- Applebaum MA, Worch J, Matthay KK, et al.: Clinical features and outcomes in patients with extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma. Cancer 117 (13): 3027-32, 2011.

- Tal AL, Doshi H, Parkar F, et al.: The Utility of 18FDG PET/CT Versus Bone Scan for Identification of Bone Metastases in a Pediatric Sarcoma Population and a Review of the Literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 43 (2): 52-58, 2021.

- Costelloe CM, Chuang HH, Daw NC: PET/CT of Osteosarcoma and Ewing Sarcoma. Semin Roentgenol 52 (4): 255-268, 2017.

- Saifuddin A, Michelagnoli M, Pressney I: Skip metastases in appendicular Ewing sarcoma: relationship to distant metastases at diagnosis, chemotherapy response and overall survival. Skeletal Radiol 52 (3): 585-591, 2023.

- Campbell KM, Shulman DS, Grier HE, et al.: Role of bone marrow biopsy for staging new patients with Ewing sarcoma: A systematic review. Pediatr Blood Cancer 68 (2): e28807, 2021.

- Cotterill SJ, Ahrens S, Paulussen M, et al.: Prognostic factors in Ewing's tumor of bone: analysis of 975 patients from the European Intergroup Cooperative Ewing's Sarcoma Study Group. J Clin Oncol 18 (17): 3108-14, 2000.

- Miser JS, Krailo MD, Tarbell NJ, et al.: Treatment of metastatic Ewing's sarcoma or primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone: evaluation of combination ifosfamide and etoposide--a Children's Cancer Group and Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 22 (14): 2873-6, 2004.

- Rodríguez-Galindo C, Liu T, Krasin MJ, et al.: Analysis of prognostic factors in ewing sarcoma family of tumors: review of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital studies. Cancer 110 (2): 375-84, 2007.

- Karski EE, McIlvaine E, Segal MR, et al.: Identification of Discrete Prognostic Groups in Ewing Sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63 (1): 47-53, 2016.

- Paulussen M, Ahrens S, Craft AW, et al.: Ewing's tumors with primary lung metastases: survival analysis of 114 (European Intergroup) Cooperative Ewing's Sarcoma Studies patients. J Clin Oncol 16 (9): 3044-52, 1998.

- Paulussen M, Ahrens S, Burdach S, et al.: Primary metastatic (stage IV) Ewing tumor: survival analysis of 171 patients from the EICESS studies. European Intergroup Cooperative Ewing Sarcoma Studies. Ann Oncol 9 (3): 275-81, 1998.

- Ladenstein R, Pötschger U, Le Deley MC, et al.: Primary disseminated multifocal Ewing sarcoma: results of the Euro-EWING 99 trial. J Clin Oncol 28 (20): 3284-91, 2010.

- Applebaum MA, Goldsby R, Neuhaus J, et al.: Clinical features and outcomes in patients with Ewing sarcoma and regional lymph node involvement. Pediatr Blood Cancer 59 (4): 617-20, 2012.

- Bacci G, Longhi A, Ferrari S, et al.: Prognostic factors in non-metastatic Ewing's sarcoma tumor of bone: an analysis of 579 patients treated at a single institution with adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy between 1972 and 1998. Acta Oncol 45 (4): 469-75, 2006.

- Wallace MW, Niec JA, Ghani MOA, et al.: Distribution and Surgical Management of Visceral Ewing Sarcoma Among Children and Adolescents. J Pediatr Surg 58 (9): 1727-1735, 2023.

- Ahrens S, Hoffmann C, Jabar S, et al.: Evaluation of prognostic factors in a tumor volume-adapted treatment strategy for localized Ewing sarcoma of bone: the CESS 86 experience. Cooperative Ewing Sarcoma Study. Med Pediatr Oncol 32 (3): 186-95, 1999.

- De Ioris MA, Prete A, Cozza R, et al.: Ewing sarcoma of the bone in children under 6 years of age. PLoS One 8 (1): e53223, 2013.

- Huh WW, Daw NC, Herzog CE, et al.: Ewing sarcoma family of tumors in children younger than 10 years of age. Pediatr Blood Cancer 64 (4): , 2017.

- Ahmed SK, Randall RL, DuBois SG, et al.: Identification of Patients With Localized Ewing Sarcoma at Higher Risk for Local Failure: A Report From the Children's Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 99 (5): 1286-1294, 2017.

- Grier HE, Krailo MD, Tarbell NJ, et al.: Addition of ifosfamide and etoposide to standard chemotherapy for Ewing's sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone. N Engl J Med 348 (8): 694-701, 2003.

- Granowetter L, Womer R, Devidas M, et al.: Dose-intensified compared with standard chemotherapy for nonmetastatic Ewing sarcoma family of tumors: a Children's Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol 27 (15): 2536-41, 2009.

- Womer RB, West DC, Krailo MD, et al.: Randomized controlled trial of interval-compressed chemotherapy for the treatment of localized Ewing sarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 30 (33): 4148-54, 2012.

- Pieper S, Ranft A, Braun-Munzinger G, et al.: Ewing's tumors over the age of 40: a retrospective analysis of 47 patients treated according to the International Clinical Trials EICESS 92 and EURO-E.W.I.N.G. 99. Onkologie 31 (12): 657-63, 2008.

- Wong T, Goldsby RE, Wustrack R, et al.: Clinical features and outcomes of infants with Ewing sarcoma under 12 months of age. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62 (11): 1947-51, 2015.

- Worch J, Ranft A, DuBois SG, et al.: Age dependency of primary tumor sites and metastases in patients with Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 65 (9): e27251, 2018.

- Schlegel M, Zeumer M, Prodinger PM, et al.: Impact of Pathological Fractures on the Prognosis of Primary Malignant Bone Sarcoma in Children and Adults: A Single-Center Retrospective Study of 205 Patients. Oncology 94 (6): 354-362, 2018.

- Bramer JA, Abudu AA, Grimer RJ, et al.: Do pathological fractures influence survival and local recurrence rate in bony sarcomas? Eur J Cancer 43 (13): 1944-51, 2007.

- Applebaum MA, Goldsby R, Neuhaus J, et al.: Clinical features and outcomes in patients with secondary Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60 (4): 611-5, 2013.

- Roberts P, Burchill SA, Brownhill S, et al.: Ploidy and karyotype complexity are powerful prognostic indicators in the Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors: a study by the United Kingdom Cancer Cytogenetics and the Children's Cancer and Leukaemia Group. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 47 (3): 207-20, 2008.

- Hattinger CM, Pötschger U, Tarkkanen M, et al.: Prognostic impact of chromosomal aberrations in Ewing tumours. Br J Cancer 86 (11): 1763-9, 2002.

- Mackintosh C, Ordóñez JL, García-Domínguez DJ, et al.: 1q gain and CDT2 overexpression underlie an aggressive and highly proliferative form of Ewing sarcoma. Oncogene 31 (10): 1287-98, 2012.

- Tirode F, Surdez D, Ma X, et al.: Genomic landscape of Ewing sarcoma defines an aggressive subtype with co-association of STAG2 and TP53 mutations. Cancer Discov 4 (11): 1342-53, 2014.

- Mrózek K, Bloomfield CD: Der(16)t(1;16) is a secondary chromosome aberration in at least eighteen different types of human cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 23 (1): 78-80, 1998.

- Mugneret F, Lizard S, Aurias A, et al.: Chromosomes in Ewing's sarcoma. II. Nonrandom additional changes, trisomy 8 and der(16)t(1;16). Cancer Genet Cytogenet 32 (2): 239-45, 1988.

- Hattinger CM, Rumpler S, Ambros IM, et al.: Demonstration of the translocation der(16)t(1;16)(q12;q11.2) in interphase nuclei of Ewing tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 17 (3): 141-50, 1996.

- Dubois SG, Epling CL, Teague J, et al.: Flow cytometric detection of Ewing sarcoma cells in peripheral blood and bone marrow. Pediatr Blood Cancer 54 (1): 13-8, 2010.

- Schleiermacher G, Peter M, Oberlin O, et al.: Increased risk of systemic relapses associated with bone marrow micrometastasis and circulating tumor cells in localized ewing tumor. J Clin Oncol 21 (1): 85-91, 2003.

- Zoubek A, Ladenstein R, Windhager R, et al.: Predictive potential of testing for bone marrow involvement in Ewing tumor patients by RT-PCR: a preliminary evaluation. Int J Cancer 79 (1): 56-60, 1998.

- Shukla NN, Patel JA, Magnan H, et al.: Plasma DNA-based molecular diagnosis, prognostication, and monitoring of patients with EWSR1 fusion-positive sarcomas. JCO Precis Oncol 2017: , 2017.

- Shulman DS, Klega K, Imamovic-Tuco A, et al.: Detection of circulating tumour DNA is associated with inferior outcomes in Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Br J Cancer 119 (5): 615-621, 2018.

- Krumbholz M, Eiblwieser J, Ranft A, et al.: Quantification of Translocation-Specific ctDNA Provides an Integrating Parameter for Early Assessment of Treatment Response and Risk Stratification in Ewing Sarcoma. Clin Cancer Res 27 (21): 5922-5930, 2021.

- Vo KT, Edwards JV, Epling CL, et al.: Impact of Two Measures of Micrometastatic Disease on Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Ewing Sarcoma: A Report from the Children's Oncology Group. Clin Cancer Res 22 (14): 3643-50, 2016.

- Lerman DM, Monument MJ, McIlvaine E, et al.: Tumoral TP53 and/or CDKN2A alterations are not reliable prognostic biomarkers in patients with localized Ewing sarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62 (5): 759-65, 2015.

- Shulman DS, Chen S, Hall D, et al.: Adverse prognostic impact of the loss of STAG2 protein expression in patients with newly diagnosed localised Ewing sarcoma: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Br J Cancer 127 (12): 2220-2226, 2022.

- Parham DM, Hijazi Y, Steinberg SM, et al.: Neuroectodermal differentiation in Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors does not predict tumor behavior. Hum Pathol 30 (8): 911-8, 1999.

- Luksch R, Sampietro G, Collini P, et al.: Prognostic value of clinicopathologic characteristics including neuroectodermal differentiation in osseous Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors in children. Tumori 85 (2): 101-7, 1999 Mar-Apr.

- de Alava E, Kawai A, Healey JH, et al.: EWS-FLI1 fusion transcript structure is an independent determinant of prognosis in Ewing's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 16 (4): 1248-55, 1998.

- van Doorninck JA, Ji L, Schaub B, et al.: Current treatment protocols have eliminated the prognostic advantage of type 1 fusions in Ewing sarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 28 (12): 1989-94, 2010.

- Le Deley MC, Delattre O, Schaefer KL, et al.: Impact of EWS-ETS fusion type on disease progression in Ewing's sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor: prospective results from the cooperative Euro-E.W.I.N.G. 99 trial. J Clin Oncol 28 (12): 1982-8, 2010.

- Paulussen M, Ahrens S, Dunst J, et al.: Localized Ewing tumor of bone: final results of the cooperative Ewing's Sarcoma Study CESS 86. J Clin Oncol 19 (6): 1818-29, 2001.

- Rosito P, Mancini AF, Rondelli R, et al.: Italian Cooperative Study for the treatment of children and young adults with localized Ewing sarcoma of bone: a preliminary report of 6 years of experience. Cancer 86 (3): 421-8, 1999.

- Wunder JS, Paulian G, Huvos AG, et al.: The histological response to chemotherapy as a predictor of the oncological outcome of operative treatment of Ewing sarcoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am 80 (7): 1020-33, 1998.

- Oberlin O, Deley MC, Bui BN, et al.: Prognostic factors in localized Ewing's tumours and peripheral neuroectodermal tumours: the third study of the French Society of Paediatric Oncology (EW88 study). Br J Cancer 85 (11): 1646-54, 2001.

- Lozano-Calderón SA, Albergo JI, Groot OQ, et al.: Complete tumor necrosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy defines good responders in patients with Ewing sarcoma. Cancer 129 (1): 60-70, 2023.

- Ferrari S, Bertoni F, Palmerini E, et al.: Predictive factors of histologic response to primary chemotherapy in patients with Ewing sarcoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 29 (6): 364-8, 2007.

- Hawkins DS, Schuetze SM, Butrynski JE, et al.: [18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography predicts outcome for Ewing sarcoma family of tumors. J Clin Oncol 23 (34): 8828-34, 2005.

- Denecke T, Hundsdörfer P, Misch D, et al.: Assessment of histological response of paediatric bone sarcomas using FDG PET in comparison to morphological volume measurement and standardized MRI parameters. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 37 (10): 1842-53, 2010.

- Palmerini E, Colangeli M, Nanni C, et al.: The role of FDG PET/CT in patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy for localized bone sarcomas. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 44 (2): 215-223, 2017.

- Lin PP, Jaffe N, Herzog CE, et al.: Chemotherapy response is an important predictor of local recurrence in Ewing sarcoma. Cancer 109 (3): 603-11, 2007.

- Bosma SE, Rueten-Budde AJ, Lancia C, et al.: Individual risk evaluation for local recurrence and distant metastasis in Ewing sarcoma: A multistate model: A multistate model for Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 66 (11): e27943, 2019.

- Reiter AJ, Huang L, Craig BT, et al.: Survival outcomes in pediatric patients with metastatic Ewing sarcoma who achieve a rapid complete response of pulmonary metastases. Pediatr Blood Cancer 71 (7): e31026, 2024.

Cellular Classification of Ewing Sarcoma

Ewing sarcoma belongs to the group of neoplasms commonly referred to as small round blue cell tumors of childhood. The individual cells of Ewing sarcoma contain round-to-oval nuclei, with fine dispersed chromatin without nucleoli. Occasionally, cells with smaller, more hyperchromatic, and probably degenerative nuclei are present, giving a light cell/dark cell pattern. The cytoplasm varies in amount, but in the classic case, it is clear and contains glycogen, which can be highlighted with a periodic acid-Schiff stain. The tumor cells are tightly packed and grow in a diffuse pattern without evidence of structural organization. Tumors with the requisite translocation that show neuronal differentiation are not considered a separate entity, but rather, part of a continuum of differentiation.

CD99 is a surface membrane protein that is expressed in most cases of Ewing sarcoma and is useful in diagnosing these tumors when the results are interpreted in the context of clinical and pathological parameters.[

For more information about the cellular classification of other undifferentiated small round cell sarcomas, see the

References:

- Parham DM, Hijazi Y, Steinberg SM, et al.: Neuroectodermal differentiation in Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors does not predict tumor behavior. Hum Pathol 30 (8): 911-8, 1999.

- Yoshida A, Sekine S, Tsuta K, et al.: NKX2.2 is a useful immunohistochemical marker for Ewing sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 36 (7): 993-9, 2012.

Genomics of Ewing Sarcoma

Molecular Features of Ewing Sarcoma

The World Health Organization identifies the presence of a gene fusion involving EWSR1 or FUS and a gene in the ETS family as a defining element of Ewing sarcoma.[

The EWSR1::FLI1 translocation associated with Ewing sarcoma can occur at several potential breakpoints in each of the genes that join to form the novel segment of DNA. Once thought to be significant,[

Besides the consistent aberrations involving the EWSR1 gene, secondary numerical and structural chromosomal aberrations are observed in most cases of Ewing sarcoma. Chromosome gains are more common than chromosome losses, and structural chromosome imbalances are also observed.[

- Gain of whole chromosome 8 (trisomy 8). Trisomy 8 is the most frequent chromosomal alteration in Ewing sarcoma, occurring in nearly 50% of tumors.[

3 ,4 ] Gain of chromosome 8 does not appear to have prognostic significance.[3 ,12 ] - Gain of chromosome 1q and loss of chromosome 16q. These occur in approximately 20% of patients and often occur together. Gain of chromosome 1q and/or deletion of chromosome 16q has been associated with inferior prognosis for patients with Ewing sarcoma in several cohorts.[

3 ,13 ,14 ] These two chromosomal alterations commonly occur together across a range of cancer types, including Ewing sarcoma.[15 ] Their co-occurrence is likely a result of their derivation from an unbalanced t(1;16) translocation resulting in gain of chromosome 1q together with loss of chromosomal material from 16q.[12 ,16 ]

The genomic landscape of Ewing sarcoma is characterized by a relatively silent genome, with a paucity of variants in pathways that might be amenable to treatment with novel targeted therapies.[

- STAG2 variants. Variants in STAG2, a member of the cohesin complex, occur in about 15% to 20% of the cases.[

3 ,4 ,5 ] These variants lead to loss of STAG2 expression and function in tumor cells.[5 ] Loss of STAG2 expression (detected by immunohistochemistry [IHC]) has been observed in tumors in which a STAG2 variant cannot be detected. In one report, loss of STAG2 expression by IHC was associated with inferior prognosis.[17 ] - CDKN2A deletions. CDKN2A deletions have been noted in 12% to 22% of cases.[

3 ,4 ,5 ] - TP53 variants. TP53 variants were identified in about 6% to 7% of Ewing sarcoma cases reported by pediatric research teams.[

3 ,4 ,5 ] Higher rates of TP53 variants (up to 19%) have been described in cohorts from single institutions that contain higher proportions of adult patients.[18 ,19 ] The coexistence of STAG2 and TP53 variants has been associated with a poor clinical outcome in one retrospective report. - ERF alterations. Genomic alterations in ERF leading to loss of function (frameshift, missense, and deep deletion) were reported in 7% of Ewing sarcoma tumors.[

18 ] A second report observed ERF alterations at a rate of 3% in another Ewing sarcoma cohort.[4 ] - Other genes with recurring genomic alterations in Ewing sarcoma. Recurring genomic alterations present in fewer than 5% of Ewing sarcoma patients were reported: EZH2,[

3 ,19 ]BCOR,[3 ]SMARCA4,[19 ]CREBBP,[19 ]TERT, and FGFR1.[18 ]

Ewing sarcoma translocations can all be found with standard cytogenetic analysis. A fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) rapid analysis looking for a break apart of the EWSR1 gene is now frequently done to confirm the diagnosis of Ewing sarcoma molecularly.[

| FET Family Partner | Fusion With ETS-Like Oncogene Partner | Translocation | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| a These partners are not members of the ETS family of oncogenes; therefore, these tumors are not classified as Ewing sarcoma. | |||

| EWSR1 | EWSR1::FLI1 | t(11;22)(q24;q12) | Most common; approximately 85% to 90% of cases |

| EWSR1::ERG | t(21;22)(q22;q12) | Second most common; approximately 10% of cases | |

| EWSR1::ETV1 | t(7;22)(p22;q12) | Rare | |

| EWSR1::ETV4 | t(17;22)(q12;q12) | Rare | |

| EWSR1::FEV | t(2;22)(q35;q12) | Rare | |

| EWSR1::NFATC2a | t(20;22)(q13;q12) | Rare | |

| EWSR1::POU5F1a | t(6;22)(p21;q12) | ||

| EWSR1::SMARCA5a | t(4;22)(q31;q12) | Rare | |

| EWSR1::PATZ1a | t(6;22)(p21;q12) | ||

| EWSR1::SP3a | t(2;22)(q31;q12) | Rare | |

| FUS | FUS::ERG | t(16;21)(p11;q22) | Rare |

| FUS::FEV | t(2;16)(q35;p11) | Rare | |

References:

- WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board: WHO Classification of Tumours. Volume 3: Soft Tissue and Bone Tumours. 5th ed., IARC Press, 2020.

- Schwartz JC, Cech TR, Parker RR: Biochemical Properties and Biological Functions of FET Proteins. Annu Rev Biochem 84: 355-79, 2015.

- Tirode F, Surdez D, Ma X, et al.: Genomic landscape of Ewing sarcoma defines an aggressive subtype with co-association of STAG2 and TP53 mutations. Cancer Discov 4 (11): 1342-53, 2014.

- Crompton BD, Stewart C, Taylor-Weiner A, et al.: The genomic landscape of pediatric Ewing sarcoma. Cancer Discov 4 (11): 1326-41, 2014.

- Brohl AS, Solomon DA, Chang W, et al.: The genomic landscape of the Ewing Sarcoma family of tumors reveals recurrent STAG2 mutation. PLoS Genet 10 (7): e1004475, 2014.

- Hattinger CM, Rumpler S, Strehl S, et al.: Prognostic impact of deletions at 1p36 and numerical aberrations in Ewing tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 24 (3): 243-54, 1999.

- Sankar S, Lessnick SL: Promiscuous partnerships in Ewing's sarcoma. Cancer Genet 204 (7): 351-65, 2011.

- de Alava E, Kawai A, Healey JH, et al.: EWS-FLI1 fusion transcript structure is an independent determinant of prognosis in Ewing's sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 16 (4): 1248-55, 1998.

- van Doorninck JA, Ji L, Schaub B, et al.: Current treatment protocols have eliminated the prognostic advantage of type 1 fusions in Ewing sarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 28 (12): 1989-94, 2010.

- Le Deley MC, Delattre O, Schaefer KL, et al.: Impact of EWS-ETS fusion type on disease progression in Ewing's sarcoma/peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor: prospective results from the cooperative Euro-E.W.I.N.G. 99 trial. J Clin Oncol 28 (12): 1982-8, 2010.

- Roberts P, Burchill SA, Brownhill S, et al.: Ploidy and karyotype complexity are powerful prognostic indicators in the Ewing's sarcoma family of tumors: a study by the United Kingdom Cancer Cytogenetics and the Children's Cancer and Leukaemia Group. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 47 (3): 207-20, 2008.

- Hattinger CM, Rumpler S, Ambros IM, et al.: Demonstration of the translocation der(16)t(1;16)(q12;q11.2) in interphase nuclei of Ewing tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 17 (3): 141-50, 1996.

- Hattinger CM, Pötschger U, Tarkkanen M, et al.: Prognostic impact of chromosomal aberrations in Ewing tumours. Br J Cancer 86 (11): 1763-9, 2002.

- Mackintosh C, Ordóñez JL, García-Domínguez DJ, et al.: 1q gain and CDT2 overexpression underlie an aggressive and highly proliferative form of Ewing sarcoma. Oncogene 31 (10): 1287-98, 2012.

- Mrózek K, Bloomfield CD: Der(16)t(1;16) is a secondary chromosome aberration in at least eighteen different types of human cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 23 (1): 78-80, 1998.

- Mugneret F, Lizard S, Aurias A, et al.: Chromosomes in Ewing's sarcoma. II. Nonrandom additional changes, trisomy 8 and der(16)t(1;16). Cancer Genet Cytogenet 32 (2): 239-45, 1988.

- Shulman DS, Chen S, Hall D, et al.: Adverse prognostic impact of the loss of STAG2 protein expression in patients with newly diagnosed localised Ewing sarcoma: A report from the Children's Oncology Group. Br J Cancer 127 (12): 2220-2226, 2022.

- Ogura K, Elkrief A, Bowman AS, et al.: Prospective Clinical Genomic Profiling of Ewing Sarcoma: ERF and FGFR1 Mutations as Recurrent Secondary Alterations of Potential Biologic and Therapeutic Relevance. JCO Precis Oncol 6: e2200048, 2022.

- Rock A, Uche A, Yoon J, et al.: Bioinformatic Analysis of Recurrent Genomic Alterations and Corresponding Pathway Alterations in Ewing Sarcoma. J Pers Med 13 (10): , 2023.

- Monforte-Muñoz H, Lopez-Terrada D, Affendie H, et al.: Documentation of EWS gene rearrangements by fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) in frozen sections of Ewing's sarcoma-peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumor. Am J Surg Pathol 23 (3): 309-15, 1999.

- Chen S, Deniz K, Sung YS, et al.: Ewing sarcoma with ERG gene rearrangements: A molecular study focusing on the prevalence of FUS-ERG and common pitfalls in detecting EWSR1-ERG fusions by FISH. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 55 (4): 340-9, 2016.

Stage Information for Ewing Sarcoma

Pretreatment staging studies for Ewing sarcoma may include the following:

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the primary site.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan of the primary site and chest.

- Positron emission tomography using fluorine F 18-fludeoxyglucose (18F-FDG PET) or 18F-FDG PET-CT.

- Bone scan has traditionally been part of the staging evaluation for Ewing sarcoma. However, many investigators believe that PET scan can replace bone scan.[

1 ,2 ] - Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy.

For patients with confirmed Ewing sarcoma, pretreatment staging studies include MRI and/or CT scan, depending on the primary site. Despite the fact that CT and MRI are both equivalent in terms of staging, use of both imaging modalities may help radiation therapy planning.[

18F-FDG PET-CT scans have demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in Ewing sarcoma and are now routinely used to complete staging. In one institutional study, 18F-FDG PET had a very high correlation with bone scan; the investigators suggested that it could replace bone scan for the initial extent of disease evaluation.[

Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy have been considered the standard of care for Ewing sarcoma. However, two retrospective studies showed that for patients (N = 141) who were evaluated by bone scan and/or PET scan and lung CT without evidence of metastases, bone marrow aspirates and biopsies were negative in every case.[

For Ewing sarcoma, tumors are practically staged as localized or metastatic, and other staging systems are not commonly used. The tumor is defined as localized when, by clinical and imaging techniques, there is no spread beyond the primary site or regional lymph node involvement. Continuous extension into adjacent soft tissue may occur. If there is a question of regional lymph node involvement, pathological confirmation is indicated.

References:

- Costelloe CM, Chuang HH, Daw NC: PET/CT of Osteosarcoma and Ewing Sarcoma. Semin Roentgenol 52 (4): 255-268, 2017.

- Tal AL, Doshi H, Parkar F, et al.: The Utility of 18FDG PET/CT Versus Bone Scan for Identification of Bone Metastases in a Pediatric Sarcoma Population and a Review of the Literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 43 (2): 52-58, 2021.

- Meyer JS, Nadel HR, Marina N, et al.: Imaging guidelines for children with Ewing sarcoma and osteosarcoma: a report from the Children's Oncology Group Bone Tumor Committee. Pediatr Blood Cancer 51 (2): 163-70, 2008.

- Mentzel HJ, Kentouche K, Sauner D, et al.: Comparison of whole-body STIR-MRI and 99mTc-methylene-diphosphonate scintigraphy in children with suspected multifocal bone lesions. Eur Radiol 14 (12): 2297-302, 2004.

- Newman EN, Jones RL, Hawkins DS: An evaluation of [F-18]-fluorodeoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography, bone scan, and bone marrow aspiration/biopsy as staging investigations in Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60 (7): 1113-7, 2013.

- Ulaner GA, Magnan H, Healey JH, et al.: Is methylene diphosphonate bone scan necessary for initial staging of Ewing sarcoma if 18F-FDG PET/CT is performed? AJR Am J Roentgenol 202 (4): 859-67, 2014.

- Völker T, Denecke T, Steffen I, et al.: Positron emission tomography for staging of pediatric sarcoma patients: results of a prospective multicenter trial. J Clin Oncol 25 (34): 5435-41, 2007.

- Gerth HU, Juergens KU, Dirksen U, et al.: Significant benefit of multimodal imaging: PET/CT compared with PET alone in staging and follow-up of patients with Ewing tumors. J Nucl Med 48 (12): 1932-9, 2007.

- Treglia G, Salsano M, Stefanelli A, et al.: Diagnostic accuracy of ¹⁸F-FDG-PET and PET/CT in patients with Ewing sarcoma family tumours: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Skeletal Radiol 41 (3): 249-56, 2012.

- Kopp LM, Hu C, Rozo B, et al.: Utility of bone marrow aspiration and biopsy in initial staging of Ewing sarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 62 (1): 12-5, 2015.

- Cesari M, Righi A, Colangeli M, et al.: Bone marrow biopsy in the initial staging of Ewing sarcoma: Experience from a single institution. Pediatr Blood Cancer 66 (6): e27653, 2019.

Treatment Option Overview for Ewing Sarcoma

It is important that patients be evaluated by specialists from the appropriate disciplines (e.g., medical oncologists, surgical or orthopedic oncologists, and radiation oncologists) as early as possible. Multidisciplinary review with radiologists and pathologists is often performed at sarcoma specialty centers.

Appropriate imaging studies of the suspected primary site are obtained before biopsy. To ensure that the biopsy incision is placed in an acceptable location, the surgical or orthopedic oncologist (who will perform the definitive surgery) is consulted on biopsy-incision placement. This is especially important if it is thought that the lesion can subsequently be totally excised after initial systemic therapy or if a limb salvage procedure may be attempted. It is almost never appropriate to attempt a primary resection of known Ewing sarcoma at initial diagnosis. With rare exceptions, Ewing sarcoma is sensitive to chemotherapy and will respond to initial systemic therapy. This therapy reduces the risk of tumor spread to surrounding tissues and makes ultimate surgery easier and safer. Biopsy should be from soft tissue as often as possible to avoid increasing the risk of fracture.[

| Treatment Group | Standard Treatment Options | |

|---|---|---|

| Localized Ewing sarcoma | |

|

| |

||

| |

||

| |

||

| |

||

| Metastatic Ewing sarcoma | |

|

| |

||

| |

||

| Recurrent Ewing sarcoma | |

|

| |

||

| |

||

| |

||

| |

||

The successful treatment of patients with Ewing sarcoma requires systemic chemotherapy [

Chemotherapy for Ewing Sarcoma

Multidrug chemotherapy for Ewing sarcoma always includes vincristine, doxorubicin, ifosfamide, and etoposide. Most protocols also use cyclophosphamide and some incorporate dactinomycin. The mode of administration and dose intensity of cyclophosphamide within courses differs markedly between protocols. A European Intergroup Cooperative Ewing Sarcoma Study (EICESS) trial suggested that 1.2 g of cyclophosphamide produced a similar event-free survival (EFS) compared with 6 g of ifosfamide in patients with lower-risk disease. The trial also identified a trend toward better EFS for patients with localized Ewing sarcoma and higher-risk disease when treatment included etoposide (GER-GPOH-EICESS-92 [NCT00002516]).[

Protocols in the United States generally alternate courses of vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin (VDC) with courses of ifosfamide and etoposide (IE),[

Evidence (chemotherapy):

- An international consortium of European countries conducted the EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 (NCT00020566) trial from 2000 to 2010.[

28 ][Level of evidence A1] All patients received induction therapy with six cycles of vincristine, ifosfamide, doxorubicin, and etoposide (VIDE), followed by local control, and then one cycle of vincristine, dactinomycin, and ifosfamide (VAI). Patients were classified as standard risk if they had localized disease and good histological response to therapy or if they had localized tumors less than 200 mL in volume at presentation; they were treated with radiation therapy alone as local treatment. Standard-risk patients (n = 856) were randomly assigned to receive maintenance therapy with either seven cycles of vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide (VAC) or VAI.- There was no significant difference in EFS or overall survival (OS) between patients who received VAC and patients who received VAI.

- The 3-year EFS rate for this low-risk population was 77%.

- It is difficult to compare this outcome with that of other large series because the study population excluded patients with poor response to initial therapy or patients with tumors more than 200 mL in volume who received local-control therapy with radiation alone. All other published series report results for all patients who present without clinically detectable metastasis; thus, these other series included patients with poor response and patients with larger primary tumors treated with radiation alone, all of whom were excluded from the EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 study.

- In a Children's Oncology Group (COG) study (COG-AEWS0031 [NCT00006734]), patients presenting without metastases were randomly assigned to receive cycles of VDC alternating with cycles of IE at either 2-week or 3-week intervals.[

24 ]- The administration of cycles of VDC/IE at 2-week intervals achieved superior EFS (5-year EFS rate, 73%) than did alternating cycles at 3-week intervals (5-year EFS rate, 65%). With longer follow-up, the advantage of interval-compressed chemotherapy was confirmed.[

25 ] - The 10-year EFS rate was 70% using interval-compressed chemotherapy, compared with 61% using standard-timing chemotherapy (P = .03). The 10-year OS rate was 76% using interval-compressed chemotherapy, compared with 69% using standard-timing chemotherapy (P = .04).

- The administration of cycles of VDC/IE at 2-week intervals achieved superior EFS (5-year EFS rate, 73%) than did alternating cycles at 3-week intervals (5-year EFS rate, 65%). With longer follow-up, the advantage of interval-compressed chemotherapy was confirmed.[

- The EE2012 trial was an international multicenter phase III study that included two randomized treatments, the European VIDE induction regimen and the North American standard VDC/IE induction regimen. Patients with both localized and metastatic Ewing sarcoma were eligible for the study.[

27 ][Level of evidence B1]- The hazard ratios (HRs) for EFS (0.71) and OS (0.62) favored VDC/IE over VIDE. The posterior probabilities were 99% for both EFS and OS, which showed that VDC/IE was superior.

- Rates of febrile neutropenia were higher with the VIDE regimen. There were no other major differences in acute toxicities between the two regimens.

- The benefit of VDC/IE over VIDE was seen across subgroups defined by patient age, sex, stage, tumor volume, or country of residence.

- The Brazilian Cooperative Study Group performed a multi-institutional trial that incorporated carboplatin into a risk-adapted intensive regimen in 175 children with localized or metastatic Ewing sarcoma.[

29 ][Level of evidence B4]- The investigators found significantly increased toxicity without an improvement in outcome with the addition of carboplatin.

- The COG performed a prospective randomized trial in patients with localized Ewing sarcoma. All patients received cycles of VDC and cycles of IE. Patients were then randomly assigned to receive or not receive additional experimental cycles of vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and topotecan.[

26 ]- The 5-year EFS rate was 78% (95% confidence interval [CI], 72%–82%) for those treated with experimental therapy and 79% (95% CI, 74%–83%) for patients treated with standard therapy.

- The experimental therapy did not significantly reduce the risk of events (EFS HR for experimental arm vs. standard arm, 0.86; 1-sided P = .19).

Local Control (Surgery and Radiation Therapy) for Ewing Sarcoma

Treatment approaches for Ewing sarcoma and therapeutic aggressiveness must be adjusted to maximize local control while also minimizing morbidity.

Surgery is the most commonly used form of local control.[

Timing of local control may impact outcome. A retrospective review from the National Cancer Database identified 1,318 patients with Ewing sarcoma.[

For patients with metastatic Ewing sarcoma, any benefit of combined surgery and radiation therapy compared with either therapy alone for local control is relatively less substantial because the overall prognosis of these patients is much worse than the prognosis of patients who have localized disease.

Randomized trials that directly compare surgery and radiation therapy do not exist, and their relative roles remain controversial. Although retrospective institutional series suggest better local control and survival with surgery than with radiation therapy, most of these studies are compromised by selection bias. An analysis using propensity scoring to adjust for clinical features that may influence the preference for surgery only, radiation only, or combined surgery and radiation demonstrated that similar EFS is achieved with each mode of local therapy.[

The EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 (NCT00020566) trial prospectively treated 180 patients with pelvic primary tumors without clinically detectable metastatic disease.[

For patients who undergo gross-total resection with microscopic residual disease, a radiation therapy dose of 50.4 Gy is recommended. For patients treated with primary radiation therapy, the radiation dose is 55.8 Gy (45 Gy to the initial tumor volume and an additional 10.8 Gy to the postchemotherapy volume).[

Evidence (postoperative radiation therapy):

- Investigators from St. Jude Children's Research Hospital reported 39 patients with localized Ewing sarcoma who received both surgery and radiation.[

14 ]- The local failure rate for patients with positive margins was 17%, and the OS rate was 71%.

- The local failure rate for patients with negative margins was 5%, and the OS rate was 94%.

- In a large retrospective Italian study, 45 Gy of adjuvant radiation therapy for patients with inadequate margins did not appear to improve either local control or disease-free survival (DFS).[

15 ]- These investigators concluded that patients who are anticipated to have suboptimal surgery should be considered for definitive radiation therapy.

- The EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 (NCT00020566) study reported the outcomes of 599 patients who presented with localized disease and had surgical resection after initial chemotherapy with at least 90% necrosis of the primary tumor.[

34 ][Level of evidence C2] The protocol recommended postoperative radiation therapy for patients with inadequate surgical margins, vertebral primary tumors, or thoracic tumors with pleural effusion, but the decision to use postoperative radiation therapy was left to the institutional investigator.- Patients who received postoperative radiation therapy (n = 142) had a lower risk of failure than patients who did not receive postoperative radiation therapy, even after controlling for known prognostic factors, including age, sex, tumor site, clinical response, quality of resection, and histological necrosis. Most of the improvement was seen in a decreased risk of local recurrence. The improvement was greater in patients who had large tumors (>200 mL) and were assessed to have 100% necrosis than in patients who were assessed to have 90% to 100% necrosis.

- There is a clear interaction between systemic therapy and local-control modalities for both local control and DFS. The induction regimen used in the EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 study is less intense than the induction regimen used in contemporaneous protocols in the COG, and it is not appropriate to extrapolate the results from the EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 study to different systemic chemotherapy regimens.

Thoracic primary tumors

Evidence (surgery):

- The treatment and outcomes for 62 patients with thoracic Ewing sarcoma were reported from the Cooperative Weichteilsarkom Studiengruppe CWS-81, -86, -91, -96, and -2002P trials.[

35 ]- The 5-year OS rate was 58.7% (95% CI, 52.7%–64.7%), and the EFS rate was 52.8% (95% CI, 46.8%–58.8%).

- Patients with intrathoracic tumors (n = 24) had a worse outcome (EFS rate, 37.5% [95% CI, 27.5%–37.5%]) than patients with chest wall tumors (n = 38; EFS rate, 62.3% [95% CI, 54.3%–70.3%]; P = .008).

- Patients aged 10 years and younger (n = 38) had a better survival (EFS rate, 65.7% [95% CI, 57.7%–73.7%]) than patients older than 10 years (EFS rate, 31.3% [95% CI, 21.3%–41.3%]; P = .01).

- Tumor size of less than or equal to 5 cm (n = 15) was associated with significantly better survival (EFS rate, 93.3% [95% CI, 87.3%–99.3%]), compared with a tumor size greater than 5 cm (n = 47; EFS rate, 40% [95% CI, 33%–47%]; P = .002).

- Primary resections were carried out in 36 patients, 75% of which were incomplete, resulting in inferior EFS (P = .006).

- Complete secondary resections were performed in 22 of 40 patients.

- The COG reviewed its results for 98 patients with chest wall tumors who were treated on the INT-0091 and INT-0154 trials from 1988 to 1998 and found the following:[

36 ]- The 5-year EFS rate was 56%.

- Negative margins were more common in patients who received initial chemotherapy and then underwent resections (41 of 53 patients, 77%) than in patients who had up-front surgery (10 of 20 patients, 50%).

- More patients who underwent up-front surgery received radiation therapy (71%) than patients who started with chemotherapy (48%).

In summary, surgery is chosen as definitive local therapy for suitable patients, but radiation therapy is appropriate for patients with unresectable disease or those who would experience functional or cosmetic compromise by definitive surgery. The possibility of impaired function or cosmesis needs to be measured against the possibility of second tumors in the radiation field. Adjuvant radiation therapy should be considered for patients with residual microscopic disease or inadequate margins.

When preoperative assessment has suggested a high probability that surgical margins will be close or positive, preoperative radiation therapy has achieved tumor shrinkage and allowed surgical resection with clear margins.[

Multiple analyses have evaluated diagnostic findings, treatment, and outcome of patients with bone lesions at the following anatomical primary sites:

- Pelvis.[

38 ,39 ,40 ] - Femur.[

41 ,42 ] - Humerus.[

43 ,44 ] - Hand and foot.[

45 ,46 ] - Chest wall/rib.[

36 ,47 ,48 ,49 ] - Head and neck.[

50 ] - Spine/sacrum.[

51 ,52 ,53 ,54 ]

High-Dose Chemotherapy With Stem Cell Support for Ewing Sarcoma

For patients with a high risk of relapse with conventional treatments, some investigators have used high-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) as consolidation treatment, in an effort to improve outcome.[

Evidence (high-dose therapy with stem cell support):

- In a prospective study, patients with bone and/or bone marrow metastases at diagnosis were treated with aggressive chemotherapy, surgery, and/or radiation therapy and HSCT if a good initial response was achieved.[

60 ]- The study showed no benefit for HSCT compared with historical controls.

- A retrospective review using international bone marrow transplant registries compared the outcomes after treatment with either reduced-intensity conditioning or high-intensity conditioning followed by allogeneic HSCT for patients with Ewing sarcoma at high risk of relapse.[

68 ][Level of evidence C1]- There was no difference in outcome, and the authors concluded that this suggested the absence of a clinically relevant graft-versus-tumor effect against Ewing sarcoma tumor cells with current approaches.

- The role of high-dose therapy with busulfan-melphalan (BuMel) followed by stem cell rescue was investigated in the prospective randomized EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 (NCT00020566) trial for two distinct groups:[

69 ]- Patients who presented with isolated pulmonary metastases (R2pulm).

- Patients with localized tumors with poor response to initial chemotherapy (<90% necrosis) or with large tumors (>200 mL) (R2loc).

Both study arms were compromised by the potential for selection bias for patients who were eligible for and accepted randomization, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Only 40% of eligible patients were randomized.

- For R2pulm patients, there was no statistically significant difference in EFS or OS between the treatment groups.[

70 ]- The EFS rates at 3 years were 50.6% for patients who received VAI plus whole-lung irradiation versus 56.6% for patients who received BuMel. The EFS rates at 8 years were 43.1% for patients who received VAI plus whole-lung irradiation versus 52.9% for patients who received BuMel.

- The OS rates at 3 years were 68.0% for patients who received VAI plus whole-lung irradiation versus 68.2% for patients who received BuMel. The OS rates at 8 years were 54.2% for patients who received VAI plus whole-lung irradiation versus 55.3% for patients who received BuMel.

- Among R2loc patients, the 3-year EFS rate was superior with BuMel compared with continued chemotherapy (66.9% vs. 53.1%; P = .019). The 3-year OS rate was 78.0% with BuMel and 72.2% with continued chemotherapy (P = .028).[

69 ]

- For R2pulm patients, there was no statistically significant difference in EFS or OS between the treatment groups.[

The induction regimen employed in the EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 trial was VIDE. This regimen is less dose intensive than the regimen employed in COG studies. This can be inferred from the intended dose intensity of the agents employed for the 21-week period that preceded randomization in the EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 study (see

Table 6 ). The lower dose intensity can also be inferred from the outcome of the EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 study for patients in the localized disease stratum. Results from this study include the following:- Patients assigned to the most favorable risk stratum, R1, were patients with small primary tumors, less than 200 mL in volume. In addition, patients who had poor response to the initial six cycles of therapy with VIDE, as assessed by pathology or radiology, were removed from the R1 stratum and assigned to the R2 stratum. As a result, the R1 stratum includes only patients with small primary tumors and favorable response to initial therapy. The probability for EFS at 3 years for this favorable group was 76%, and the OS rate at 3 years was 85%.[

28 ] - For all patients with localized Ewing sarcoma, including patients with large primary tumors and patients with poor response to initial therapy treated on the COG-AEWS1031 (NCT01231906) trial, the 5-year probability for EFS was 73%, and the 5-year OS rate was 88%.[

24 ]

The observation that high-dose therapy with autologous stem cell rescue improved outcomes for patients with a poor response to initial therapy in the EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 study must be interpreted in this context. The advantage of high-dose therapy as consolidation for patients with a poor response to initial treatment with a less intensive regimen cannot be extrapolated to a population of patients who received a more intensive treatment regimen as initial therapy.

Table 6. Comparison of the Dose Intensity of the EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 Trial Versus COG Interval Dose Compression Chemotherapy Agent Prescribed Dose Intensity (mg/week) EURO-EWING-INTERGROUP-EE99 Trial[ 28 ]COG Interval Dose Compression[ 24 ]COG = Children's Oncology Group. Vincristine 0.5 mg/m2 0.43 mg/m2 Doxorubicin 17.1 mg/m2 21.4 mg/m2 Ifosfamide 3,000 mg/m2 2,150 mg/m2 Cyclophosphamide 0 343 mg/m2 Cyclophosphamide equivalent dose (= cyclophosphamide dose + ifosfamide dose × 0.244) 732 mg/m2 868 mg/m2 - Multiple small studies that report benefit for HSCT have been published but are difficult to interpret because only patients who have a good initial response to standard chemotherapy are considered for HSCT.

Extraosseous Ewing Sarcoma

Extraosseous Ewing sarcoma is biologically similar to Ewing sarcoma arising in bone. Historically, most children and young adults with extraosseous Ewing sarcoma were treated on protocols designed for the treatment of rhabdomyosarcoma. This is important because many of the treatment regimens for rhabdomyosarcoma do not include an anthracycline, which is a critical component of current treatment regimens for Ewing sarcoma. Currently, patients with extraosseous Ewing sarcoma are eligible for studies that include Ewing sarcoma of bone.

Evidence (treatment of extraosseous Ewing sarcoma):

- From 1987 to 2004, 111 patients with nonmetastatic extraosseous Ewing sarcoma were enrolled on the RMS-88 and RMS-96 protocols.[

71 ] Patients with initial complete tumor resection received ifosfamide, vincristine, and actinomycin (IVA) while patients with residual tumor received IVA plus doxorubicin (VAIA) or IVA plus carboplatin, epirubicin, and etoposide (CEVAIE). Seventy-six percent of patients received radiation.- The 5-year EFS rate was 59%, and the OS rate was 69%.

- In a multivariate analysis, independent adverse prognostic factors included axial primary, tumor size greater than 10 cm, Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Studies Group III, and lack of radiation therapy.

- In a retrospective French study, patients with extraosseous Ewing sarcoma were treated using a rhabdomyosarcoma regimen (no anthracyclines) or a Ewing sarcoma regimen (includes anthracyclines).[

72 ,73 ]- Patients who received the anthracycline-containing regimen had a significantly better EFS and OS than patients who did not receive anthracyclines.

- Two North American Ewing sarcoma trials included patients with extraosseous Ewing sarcoma.[

24 ,74 ] In a review of data from the POG-9354 (INT-0154) and EWS0031 (NCT00006734) studies, 213 patients with extraosseous Ewing sarcoma and 826 patients with Ewing sarcoma of bone were identified.[75 ][Level of evidence C2]- The HR for EFS of extraosseous Ewing sarcoma was superior (0.62), and extraosseous Ewing sarcoma was a favorable risk factor, independent of age, race, and primary site.

- In addition to the above review, the COG AEWS1031 (NCT01231906) trial subsequently treated patients using a compressed chemotherapy schedule (every 2 weeks). Patients were randomly assigned to receive standard cycles of vincristine, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide, alternating with either ifosfamide and etoposide or vincristine, topotecan and cyclophosphamide every third cycle. There were 116 patients with extraosseous tumors, 114 patients with pelvic bone tumors, and 399 patients with nonpelvic bone tumors.[

26 ]- There were no differences in patient outcomes between the treatment regimens.

- The 5-year EFS rates were 75% (95% CI, 65%–82%) for patients with pelvic bone tumors, 78% (95% CI, 73%–81%) for patients with nonpelvic bone tumors, and 85% (95% CI, 76%–90%) for patients with extraosseous primary sites (global P value = .124).

- The Cooperative Weichteilsarkomstudiengruppe (CWS) performed a retrospective analysis of 243 patients with nonmetastatic extraosseous Ewing sarcoma treated on three consecutive soft tissue sarcoma studies between 1991 and 2008. Several different drug regimens were used, all containing vincristine, doxorubicin, and alkylating agents.[

76 ]- The outcome improved over time, but it was difficult to assign causality to any specific therapy with these historical comparisons.

- Patients with extremity primary tumors (compared with other locations) and patients with smaller tumors had better outcomes.

- The 5-year EFS rate varied, from 57% to 79%, with the better outcome seen in the most recent protocol.

Cutaneous Ewing sarcoma is a soft tissue tumor in the skin or subcutaneous tissue that seems to behave as a less-aggressive tumor than primary bone or soft tissue Ewing sarcoma. Tumors can form throughout the body, although the extremity is the most common site, and they are almost always localized.

Evidence (treatment of cutaneous Ewing sarcoma):

- In a review of 78 reported cases (some lacking molecular confirmation), the OS rate was 91%. Adequate local control, defined as a complete resection with negative margins, radiation therapy, or a combination, significantly reduced the incidence of relapse. Standard chemotherapy for Ewing sarcoma is often used for these patients because there are no data to suggest which patients could be treated less aggressively.[

77 ,78 ] - A series of 56 patients with cutaneous or subcutaneous Ewing sarcoma confirmed the excellent outcome with the use of standard systemic therapy and local control. Attempted primary definitive surgery often resulted in the need for either radiation therapy or more function-compromising surgery, supporting the recommendation of biopsy only as initial surgery, rather than up-front unplanned resection.[

79 ][Level of evidence C2]

References:

- Fuchs B, Valenzuela RG, Sim FH: Pathologic fracture as a complication in the treatment of Ewing's sarcoma. Clin Orthop (415): 25-30, 2003.

- Singh VM, Salunga RC, Huang VJ, et al.: Analysis of the effect of various decalcification agents on the quantity and quality of nucleic acid (DNA and RNA) recovered from bone biopsies. Ann Diagn Pathol 17 (4): 322-6, 2013.

- Hoffer FA, Gianturco LE, Fletcher JA, et al.: Percutaneous biopsy of peripheral primitive neuroectodermal tumors and Ewing's sarcomas for cytogenetic analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 162 (5): 1141-2, 1994.

- Craft A, Cotterill S, Malcolm A, et al.: Ifosfamide-containing chemotherapy in Ewing's sarcoma: The Second United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group and the Medical Research Council Ewing's Tumor Study. J Clin Oncol 16 (11): 3628-33, 1998.

- Shankar AG, Pinkerton CR, Atra A, et al.: Local therapy and other factors influencing site of relapse in patients with localised Ewing's sarcoma. United Kingdom Children's Cancer Study Group (UKCCSG). Eur J Cancer 35 (12): 1698-704, 1999.

- Nilbert M, Saeter G, Elomaa I, et al.: Ewing's sarcoma treatment in Scandinavia 1984-1990--ten-year results of the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group Protocol SSGIV. Acta Oncol 37 (4): 375-8, 1998.

- Ferrari S, Mercuri M, Rosito P, et al.: Ifosfamide and actinomycin-D, added in the induction phase to vincristine, cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin, improve histologic response and prognosis in patients with non metastatic Ewing's sarcoma of the extremity. J Chemother 10 (6): 484-91, 1998.

- Grier HE, Krailo MD, Tarbell NJ, et al.: Addition of ifosfamide and etoposide to standard chemotherapy for Ewing's sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone. N Engl J Med 348 (8): 694-701, 2003.

- Thacker MM, Temple HT, Scully SP: Current treatment for Ewing's sarcoma. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 5 (2): 319-31, 2005.

- Juergens C, Weston C, Lewis I, et al.: Safety assessment of intensive induction with vincristine, ifosfamide, doxorubicin, and etoposide (VIDE) in the treatment of Ewing tumors in the EURO-E.W.I.N.G. 99 clinical trial. Pediatr Blood Cancer 47 (1): 22-9, 2006.