Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage

Plans through your employer

Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

Learn

Living or working abroad?

Financial Toxicity and Cancer Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment - Health Professional Information [NCI]

Financial Toxicity Associated With Cancer Care—Background and Prevalence

Introduction

A number of studies demonstrate that individuals with cancer are at higher risk of experiencing financial difficulty than are individuals without cancer.[

Background

Cancer is one of the most costly medical conditions to treat in the United States.[

At the same time, commercial insurers in the United States are shifting more direct medical care costs to patients through higher premiums, deductibles, and coinsurance and copayment rates. The 2016 Commonwealth Fund Biennial Health Insurance Survey indicated that 33% of insured adults aged 19 to 64 years had medical bill problems or accrued medical debt.[

Oral cancer drug–based treatments are frequently covered under patient pharmacy benefits' specialty tier, requiring high coinsurance that patients pay out of pocket. High cost-sharing plans, including tiered outpatient prescription formularies (i.e., copays that escalate depending on whether the drug is generic or branded, and by price) may be particularly troublesome for patients with cancer who are prescribed expensive oral chemotherapeutics. The proportion of health care plans with multitiered (>3) prescription formularies, in which expensive oral specialty drugs are associated with the highest cost sharing, increased from 3% in 2004 to nearly 88% in 2017.[

Compared with individuals without a cancer history, cancer survivors have higher out-of-pocket costs, even many years after initial diagnosis,[

A number of other terms have been used to describe the financial impact of cancer, its treatment, and the lasting effects of treatment, including financial distress, financial stress, financial hardship, financial burden, economic burden, and economic hardship.[

Etiology and Risk Factors

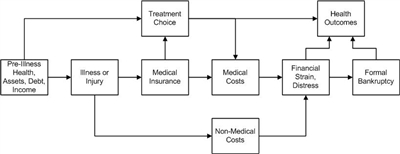

The interplay between cancer and financial distress is complex and related to a number of factors, as shown in

Figure 1. Conceptual framework relating severe illness, treatment choice, and health and financial outcomes. Credit: Scott Ramsey, MD, PhD.

Several factors in a household at the time a member of that household is diagnosed with cancer influence vulnerability to financial distress. The risk of severe financial distress and the period between illness and these outcomes are influenced by the following factors:

- Wage-earner status of the affected household member (primary, secondary, etc.).

- Pre-illness debt load.

- Assets.

- Illness-associated costs.

- The influence of the illness and its treatment on ability to work.

- The presence and terms of the health and disability insurance of the patient.

- Incomes of others in the household.

At the time of cancer diagnosis, several factors that determine the long-range risk of financial hardship include the following:

- The general health and noncancer comorbidities of the patient.

- Assets.

- Existing debt.

- Household income.

- A household with income from other sources, such as a spouse or family member who works outside the home.

Components of these measures include material conditions that arise from increased out-of-pocket expenses, lower income from the inability to work, and psychological response to increased household expenses and reduced income.[

The material conditions of patients and their families that may be adversely affected by a cancer diagnosis and treatment are typically measured as follows:[

- Out-of-pocket medical costs.

- Out-of-pocket costs as a percentage of income.

- Reduction in income and assets.

- Medical debt.

- Trouble paying medical bills and for necessities (e.g., housing, food).

- Bankruptcy.

In addition, a patient's psychological response to increased financial burden associated with a cancer diagnosis and treatment is typically measured as financial stress, distress, or worry.[

Prevalence

A number of studies have measured components of at least one aspect of financial hardship,[

The following sections describe the prevalence of specific measures of financial hardship, including out-of-pocket costs, productivity loss, asset depletion and medical debt, bankruptcy, and financial distress and worry.

Prevalence of high out-of-pocket costs

Out-of-pocket costs, one of the most common measures of financial hardship, are the amounts that patients pay directly for their medical care. They include insurance copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles for prescription and nonprescription medications, hospitalizations, outpatient services, and other types of medical care.[

In a study of long-term breast cancer survivors, 18% paid between $2,001 and $5,000 in out-of-pocket expenses, and 17% paid more than $5,000.[

In a study conducted using the nationally representative Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), 4.3% of cancer survivors aged 18 to 64 years reported a high out-of-pocket burden, compared with 3.4% of those without a cancer history.[

Prevalence of productivity loss

Productivity loss is typically measured as the inability to work or pursue usual activities, days lost from work or disability days, reduction in work hours, and days spent in bed. Productivity loss may be quantified directly from employment data [

Prevalence of asset depletion and medical debt

Several studies have reported the prevalence of asset depletion and medical debt for cancer survivors, although this information is rarely reported in relation to individuals without a cancer history or before and after a cancer diagnosis. Further, most estimates are based on self-report, and little validation work has been conducted.

Studies of cancer survivors suggest that between 33% and 80% of the survivors have used savings to finance medical expenses,[

Incidence and prevalence of bankruptcy

One of the few studies to measure the incidence of financial hardship reported that 1.7% of cancer survivors filed for bankruptcy in the 5 years after diagnosis.[

Prevalence of financial stress, distress, or worry

Several studies have found a prevalence of financial stress and worry about paying medical bills for cancer ranging from 22.5% in a nationally representative sample [

Prevalence of financial hardship as a composite measure

Several studies combine multiple components of financial hardship using summary measures, scores, or measures, including the Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity (COST) measure and the Personal Financial Wellness (PFW) Scale (formerly known as the InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being [IFDFW] Scale), but the results are rarely presented in relation to the general population and can be difficult to interpret.

In a study of patients with multiple myeloma undergoing treatment at a single academic cancer center, cancer survivors had a mean COST score of 23 (range, 0–44, with lower values equivalent to higher burden).[

References:

- Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR, Guy GP, et al.: Medical costs and productivity losses of cancer survivors--United States, 2008-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 63 (23): 505-10, 2014.

- Guy GP, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR, et al.: Economic burden of cancer survivorship among adults in the United States. J Clin Oncol 31 (30): 3749-57, 2013.

- Guy GP, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al.: Estimating the health and economic burden of cancer among those diagnosed as adolescents and young adults. Health Aff (Millwood) 33 (6): 1024-31, 2014.

- Guy GP, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al.: Healthcare Expenditure Burden Among Non-elderly Cancer Survivors, 2008-2012. Am J Prev Med 49 (6 Suppl 5): S489-97, 2015.

- Bernard DS, Farr SL, Fang Z: National estimates of out-of-pocket health care expenditure burdens among nonelderly adults with cancer: 2001 to 2008. J Clin Oncol 29 (20): 2821-6, 2011.

- Davidoff AJ, Erten M, Shaffer T, et al.: Out-of-pocket health care expenditure burden for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. Cancer 119 (6): 1257-65, 2013.

- Langa KM, Fendrick AM, Chernew ME, et al.: Out-of-pocket health-care expenditures among older Americans with cancer. Value Health 7 (2): 186-94, 2004 Mar-Apr.

- Soni A: Trends in the Five Most Costly Conditions among the U.S. Civilian Institutionalized Population, 2002 and 2012. Statistical Brief 470. Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2015.

Available online . Last accessed May 28, 2024. - Bradley CJ, Yabroff KR, Warren JL, et al.: Trends in the Treatment of Metastatic Colon and Rectal Cancer in Elderly Patients. Med Care 54 (5): 490-7, 2016.

- Shih YC, Smieliauskas F, Geynisman DM, et al.: Trends in the Cost and Use of Targeted Cancer Therapies for the Privately Insured Nonelderly: 2001 to 2011. J Clin Oncol 33 (19): 2190-6, 2015.

- Conti RM, Fein AJ, Bhatta SS: National trends in spending on and use of oral oncologics, first quarter 2006 through third quarter 2011. Health Aff (Millwood) 33 (10): 1721-7, 2014.

- Gordon N, Stemmer SM, Greenberg D, et al.: Trajectories of Injectable Cancer Drug Costs After Launch in the United States. J Clin Oncol 36 (4): 319-325, 2018.

- Shih YT, Xu Y, Liu L, et al.: Rising Prices of Targeted Oral Anticancer Medications and Associated Financial Burden on Medicare Beneficiaries. J Clin Oncol 35 (22): 2482-2489, 2017.

- 2016 Biennial Health Insurance Survey. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund, 2017.

Available online. Last accessed May 28, 2024. - 2017 Employer Health Benefits Survey. San Francisco, Calif: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2017.

Available online. Last accessed May 28, 2024. - Tucker-Seeley RD, Yabroff KR: Minimizing the "financial toxicity" associated with cancer care: advancing the research agenda. J Natl Cancer Inst 108 (5): , 2016.

- de Souza JA, Yap B, Ratain MJ, et al.: User beware: we need more science and less art when measuring financial toxicity in oncology. J Clin Oncol 33 (12): 1414-5, 2015.

- Smith R, Clarke L, Berry K, et al.: A comparison of methods for linking health insurance claims with clinical records from a large cancer registry. [Abstract] Med Decis Making 21 (6): 530, 2001.

- Fay S, Hurst E, White MJ: The household bankruptcy decision. Am Econ Rev 92 (3): 706-18, 2002.

- Banegas MP, Guy GP, de Moor JS, et al.: For Working-Age Cancer Survivors, Medical Debt And Bankruptcy Create Financial Hardships. Health Aff (Millwood) 35 (1): 54-61, 2016.

- Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, et al.: Financial Hardship Associated With Cancer in the United States: Findings From a Population-Based Sample of Adult Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol 34 (3): 259-67, 2016.

- Chang S, Long SR, Kutikova L, et al.: Estimating the cost of cancer: results on the basis of claims data analyses for cancer patients diagnosed with seven types of cancer during 1999 to 2000. J Clin Oncol 22 (17): 3524-30, 2004.

- Ell K, Xie B, Wells A, et al.: Economic stress among low-income women with cancer: effects on quality of life. Cancer 112 (3): 616-25, 2008.

- Jagsi R, Pottow JA, Griffith KA, et al.: Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J Clin Oncol 32 (12): 1269-76, 2014.

- Meisenberg BR, Varner A, Ellis E, et al.: Patient Attitudes Regarding the Cost of Illness in Cancer Care. Oncologist 20 (10): 1199-204, 2015.

- Meneses K, Azuero A, Hassey L, et al.: Does economic burden influence quality of life in breast cancer survivors? Gynecol Oncol 124 (3): 437-43, 2012.

- Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al.: Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 32 (6): 1143-52, 2013.

- Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, et al.: Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: a population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol 30 (14): 1608-14, 2012.

- Regenbogen SE, Veenstra CM, Hawley ST, et al.: The personal financial burden of complications after colorectal cancer surgery. Cancer 120 (19): 3074-81, 2014.

- Veenstra CM, Regenbogen SE, Hawley ST, et al.: A composite measure of personal financial burden among patients with stage III colorectal cancer. Med Care 52 (11): 957-62, 2014.

- Wan Y, Gao X, Mehta S, et al.: Indirect costs associated with metastatic breast cancer. J Med Econ 16 (10): 1169-78, 2013.

- Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al.: The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient's experience. Oncologist 18 (4): 381-90, 2013.

- Zajacova A, Dowd JB, Schoeni RF, et al.: Employment and income losses among cancer survivors: Estimates from a national longitudinal survey of American families. Cancer 121 (24): 4425-32, 2015.

- Finkelstein EA, Tangka FK, Trogdon JG, et al.: The personal financial burden of cancer for the working-aged population. Am J Manag Care 15 (11): 801-6, 2009.

- Jagsi R, Ward KC, Abrahamse PH, et al.: Unmet need for clinician engagement regarding financial toxicity after diagnosis of breast cancer. Cancer 124 (18): 3668-3676, 2018.

- Meisenberg BR: The financial burden of cancer patients: time to stop averting our eyes. Support Care Cancer 23 (5): 1201-3, 2015.

- Huntington SF, Weiss BM, Vogl DT, et al.: Financial toxicity in insured patients with multiple myeloma: a cross-sectional pilot study. Lancet Haematol 2 (10): e408-16, 2015.

Risk Factors Associated With Financial Toxicity

Several disease-related, sociodemographic, and health insurance–related factors have been implicated as contributors to increased risk of financial toxicity among cancer patients and survivors.

Disease- and Treatment-Related Risk Factors

Patients with advanced-stage cancers, cancers requiring chemotherapy or radiation therapy, and underlying comorbidities have a higher risk of financial hardship after diagnosis than those without these characteristics.[

A similar association was seen in an analysis using data from the 2008–2010 Medical Expenditures Panel Survey (MEPS) Household Component to measure loss of employment and productivity in individuals with and without cancer.[

Another study used multiple years of the MEPS (2008‒2013) to evaluate the associations between cancer history, chronic conditions, and productivity losses.[

Receipt of cancer-directed treatment and the presence of other comorbidities were also found to be associated with higher out-of-pocket spending in the Medicare population. In a study using data from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey linked to Medicare claims (1997–2007), 2-year mean out-of-pocket spending was higher by $1,526 among patients receiving chemotherapy and by $1,470 among patients receiving radiation therapy compared with patients who did not receive treatment (P < .01).[

These studies suggest that cancer survivors across a broad age range with advanced cancers, recurrent cancers, or cancers that require treatment (likely a marker of more-advanced disease) are more likely to face higher out-of-pocket spending and are at higher risk of financial hardship. Chronic treatment-related spending in combination with inability to regain employment and income resulting from progressive disease and debility may contribute to the association between advanced disease and greater financial burden.

Sociodemographic Risk Factors

Age

A number of studies have consistently demonstrated an association between younger age at cancer diagnosis and higher risk of various types of financial hardship.[

In a study of western Washington residents with and without cancer, bankruptcy rates were highest among both cancer survivors and noncancer controls aged 20 to 34 years (10.06 and 3.15 per 1,000 person-years, respectively) and lowest among survivors and controls aged 80 to 90 years (0.94 and 0.57 per 1,000 person-years, respectively).[

In an analysis of data from the 1,202 adult cancer survivors identified from the 2011 MEPS Experiences with Cancer questionnaire, material financial hardship (defined as bankruptcy, loans, debt, inability to pay for care, or making other financial sacrifices) was more common among cancer survivors younger than 65 years compared with those aged 65 years and older (28.4% vs. 13.8%; P < .001).[

Accumulating evidence suggests that adult survivors of childhood cancers may be especially vulnerable to financial hardship.[

Financial hardship among younger patients, however, may not solely result from higher out-of-pocket spending for cancer care. In a study using data from the 2001–2008 MEPS, a higher proportion of individuals aged 55 to 64 years reported spending 20% or more of their incomes on health care and premiums relative to younger individuals aged 18 to 39 years (10.1% vs. 7.1%; P = .05). This discrepancy suggests that high out-of-pocket spending alone does not lead to financial hardship.

Income

As might be expected, cancer patients in lower-income household groups are also at increased risk of treatment-related financial hardship. No clear income threshold below which financial hardship risk markedly increases has been identified because annual household income has been categorized differently across studies. For example, in one study of cancer patients aged 18 to 64 years identified from the 2012 Livestrong survey, income between $41,000 and $80,000 and income of $40,000 or below were both associated with increased risk of borrowing money or going into debt compared with income of $81,000 and higher (OR, 2.46 and 3.52, respectively; P < .0001).

Other studies have shown increased risk of financial hardship among individuals with household incomes below $50,000 or $20,000.[

Race and ethnicity

Race and ethnicity are strongly associated with disparities in cancer health outcomes, including survival.[

In a study using data from 3,242 lung and colorectal cancer survivors participating in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS) study, African American race was associated with an increased risk of self-reported economic burden relative to White race among patients with colorectal cancer (OR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.24–2.30) after researchers adjusted for other sociodemographic and clinical factors.[

In another population-based survey of 3,133 women with breast cancer, Spanish-speaking women were at greater risk of financial decline compared with White women (OR, 2.76; P = .006). English-speaking Latina and African American women did not share this increased risk.[

Both analyses were adjusted for key demographic variables, including income, age, marital status, and education, which might also influence risk of financial hardship. Strong associations between minority race and ethnicity and financial hardship have not been demonstrated in other studies. However, these findings suggest that further research among cancer survivors is warranted.

Employment

Loss of productivity and employment can be considered both a risk factor for (predictor of) financial toxicity and a measure of financial toxicity (outcome). Several studies have shown that cancer patients experience loss of work, difficulty in returning to work, declines in income, and general loss of productivity as a result of cancer diagnoses.[

In an analysis of data from 1,202 adult cancer survivors from the 2011 MEPS Experiences with Cancer questionnaire, change in employment after diagnosis (switching to part-time work and taking extended leave) was associated with a substantially increased risk of material financial hardship compared with no change (49.1% vs. 20.2%; P < .001).[

Compared with those without cancer, cancer survivors are more likely to report being unable to work, or being limited in the amount or type of work they can do, in both the short-term (1 year) and long-term (11+ years) postdiagnosis periods.[

Health Insurance

Patients who lack health insurance coverage are at elevated risk of many adverse experiences, including substantial financial hardship, particularly in an era of rapidly rising costs for cancer care. However, the presence of health insurance does not completely shield enrollees from high levels of out-of-pocket spending on health care services.

In the Medicare population, access to supplemental insurance and Medicare Part D plans has helped shield patients from some of the out-of-pocket cost burden. In an analysis of data from MEPS 2002–2010, outpatient prescription costs for adults older than 65 years decreased by 43% after the introduction of Medicare Part D, while younger patients (not yet Medicare-eligible) did not experience a similar decline in out-of-pocket expenditures for prescription drugs over the same period.[

As the number of high-price orally administered anticancer drugs has increased, so has awareness of differences in coverage across infused and orally administered drugs for Medicare beneficiaries. Specifically, Medicare Part D, which covers orally administered or self-administered drugs, requires very high cost sharing for cancer drugs, with no out-of-pocket spending limit. One study showed that the price for a single fill of some of the most common cancer drugs under Medicare Part D (e.g., lenalidomide, ibrutinib, palbociclib, or enzalutamide) would cost a patient over $3,000 out-of-pocket. Cumulative spending over a year would exceed $10,000 for nearly all of these drugs.[

The influence of type of insurance plan on the risk of financial hardship among patients younger than 65 years has not been thoroughly explored. One study found that patients with public insurance (Medicaid or Medicare) have an increased risk of financial hardship compared with patients who have private insurance (OR, 1.95; P < .0001).[

References:

- Dowling EC, Chawla N, Forsythe LP, et al.: Lost productivity and burden of illness in cancer survivors with and without other chronic conditions. Cancer 119 (18): 3393-401, 2013.

- Allaire BT, Ekwueme DU, Guy GP, et al.: Medical Care Costs of Breast Cancer in Privately Insured Women Aged 18-44 Years. Am J Prev Med 50 (2): 270-7, 2016.

- Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, et al.: Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer 119 (20): 3710-7, 2013.

- Regenbogen SE, Veenstra CM, Hawley ST, et al.: The personal financial burden of complications after colorectal cancer surgery. Cancer 120 (19): 3074-81, 2014.

- Guy GP, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al.: Economic Burden of Chronic Conditions Among Survivors of Cancer in the United States. J Clin Oncol 35 (18): 2053-2061, 2017.

- Davidoff AJ, Erten M, Shaffer T, et al.: Out-of-pocket health care expenditure burden for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. Cancer 119 (6): 1257-65, 2013.

- Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al.: Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 32 (6): 1143-52, 2013.

- Banegas MP, Guy GP, de Moor JS, et al.: For Working-Age Cancer Survivors, Medical Debt And Bankruptcy Create Financial Hardships. Health Aff (Millwood) 35 (1): 54-61, 2016.

- Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, et al.: Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: a population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol 30 (14): 1608-14, 2012.

- Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, et al.: Financial Hardship Associated With Cancer in the United States: Findings From a Population-Based Sample of Adult Cancer Survivors. J Clin Oncol 34 (3): 259-67, 2016.

- Nathan PC, Henderson TO, Kirchhoff AC, et al.: Financial Hardship and the Economic Effect of Childhood Cancer Survivorship. J Clin Oncol 36 (21): 2198-2205, 2018.

- Nipp RD, Kirchhoff AC, Fair D, et al.: Financial Burden in Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 35 (30): 3474-3481, 2017.

- Chino F, Peppercorn J, Taylor DH, et al.: Self-reported financial burden and satisfaction with care among patients with cancer. Oncologist 19 (4): 414-20, 2014.

- Sharrocks K, Spicer J, Camidge DR, et al.: The impact of socioeconomic status on access to cancer clinical trials. Br J Cancer 111 (9): 1684-7, 2014.

- DiMartino LD, Birken SA, Mayer DK: The Relationship Between Cancer Survivors' Socioeconomic Status and Reports of Follow-up Care Discussions with Providers. J Cancer Educ 32 (4): 749-755, 2017.

- Jagsi R, Pottow JA, Griffith KA, et al.: Long-term financial burden of breast cancer: experiences of a diverse cohort of survivors identified through population-based registries. J Clin Oncol 32 (12): 1269-76, 2014.

- Pisu M, Kenzik KM, Oster RA, et al.: Economic hardship of minority and non-minority cancer survivors 1 year after diagnosis: another long-term effect of cancer? Cancer 121 (8): 1257-64, 2015.

- Jagsi R, Ward KC, Abrahamse PH, et al.: Unmet need for clinician engagement regarding financial toxicity after diagnosis of breast cancer. Cancer 124 (18): 3668-3676, 2018.

- Whitney RL, Bell JF, Reed SC, et al.: Predictors of financial difficulties and work modifications among cancer survivors in the United States. J Cancer Surviv 10 (2): 241-50, 2016.

- Palmer JD, Patel TT, Eldredge-Hindy H, et al.: Patients Undergoing Radiation Therapy Are at Risk of Financial Toxicity: A Patient-based Prospective Survey Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 101 (2): 299-305, 2018.

- Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, et al.: Burden of illness in cancer survivors: findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst 96 (17): 1322-30, 2004.

- Ekenga CC, Pérez M, Margenthaler JA, et al.: Early-stage breast cancer and employment participation after 2 years of follow-up: A comparison with age-matched controls. Cancer 124 (9): 2026-2035, 2018.

- Blinder VS, Patil S, Thind A, et al.: Return to work in low-income Latina and non-Latina white breast cancer survivors: a 3-year longitudinal study. Cancer 118 (6): 1664-74, 2012.

- Jagsi R, Hawley ST, Abrahamse P, et al.: Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy on long-term employment of survivors of early-stage breast cancer. Cancer 120 (12): 1854-62, 2014.

- Earle CC, Chretien Y, Morris C, et al.: Employment among survivors of lung cancer and colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 28 (10): 1700-5, 2010.

- Veenstra CM, Regenbogen SE, Hawley ST, et al.: Association of Paid Sick Leave With Job Retention and Financial Burden Among Working Patients With Colorectal Cancer. JAMA 314 (24): 2688-90, 2015 Dec 22-29.

- McLennan V, Ludvik D, Chambers S, et al.: Work after prostate cancer: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv 13 (2): 282-291, 2019.

- Mujahid MS, Janz NK, Hawley ST, et al.: Racial/ethnic differences in job loss for women with breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv 5 (1): 102-11, 2011.

- Tevaarwerk AJ, Lee JW, Terhaar A, et al.: Working after a metastatic cancer diagnosis: Factors affecting employment in the metastatic setting from ECOG-ACRIN's Symptom Outcomes and Practice Patterns study. Cancer 122 (3): 438-46, 2016.

- Alleaume C, Bendiane MK, Bouhnik AD, et al.: Chronic neuropathic pain negatively associated with employment retention of cancer survivors: evidence from a national French survey. J Cancer Surviv 12 (1): 115-126, 2018.

- Blinder V, Eberle C, Patil S, et al.: Women With Breast Cancer Who Work For Accommodating Employers More Likely To Retain Jobs After Treatment. Health Aff (Millwood) 36 (2): 274-281, 2017.

- Blinder V, Patil S, Eberle C, et al.: Early predictors of not returning to work in low-income breast cancer survivors: a 5-year longitudinal study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 140 (2): 407-16, 2013.

- Mujahid MS, Janz NK, Hawley ST, et al.: The impact of sociodemographic, treatment, and work support on missed work after breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 119 (1): 213-20, 2010.

- Jagsi R, Abrahamse PH, Lee KL, et al.: Treatment decisions and employment of breast cancer patients: Results of a population-based survey. Cancer 123 (24): 4791-4799, 2017.

- Dahl S, Loge JH, Berge V, et al.: Influence of radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer on work status and working life 3 years after surgery. J Cancer Surviv 9 (2): 172-9, 2015.

- Dahl S, Steinsvik EA, Dahl AA, et al.: Return to work and sick leave after radical prostatectomy: a prospective clinical study. Acta Oncol 53 (6): 744-51, 2014.

- Blinder VS, Murphy MM, Vahdat LT, et al.: Employment after a breast cancer diagnosis: a qualitative study of ethnically diverse urban women. J Community Health 37 (4): 763-72, 2012.

- Glare PA, Nikolova T, Alickaj A, et al.: Work Experiences of Patients Receiving Palliative Care at a Comprehensive Cancer Center: Exploratory Analysis. J Palliat Med 20 (7): 770-773, 2017.

- Kircher SM, Johansen ME, Nimeiri HS, et al.: Impact of Medicare Part D on out-of-pocket drug costs and medical use for patients with cancer. Cancer 120 (21): 3378-84, 2014.

- Dusetzina SB: Your Money or Your Life - The High Cost of Cancer Drugs under Medicare Part D. N Engl J Med 386 (23): 2164-2167, 2022.

- Dusetzina SB, Huskamp HA, Rothman RL, et al.: Many Medicare Beneficiaries Do Not Fill High-Price Specialty Drug Prescriptions. Health Aff (Millwood) 41 (4): 487-496, 2022.

Consequences of Financial Toxicity Among Cancer Patients

Several retrospective cohort and cross-sectional studies have investigated the associations among financial burden from cancer care and treatment adherence, quality of life, satisfaction with care, incurring debt, filing for bankruptcy, and health outcomes. Cohort and cross-sectional studies are prone to study biases inherent to such study designs; therefore, caution must be taken when interpreting the reported findings. So far, no evidence from randomized controlled clinical trials is available to guide patients and physicians about outcomes related to financial toxicity among individuals diagnosed with cancer.

Access and Adherence to Treatments

Several retrospective cohort studies have evaluated the effect of prescription copayment amounts for cancer drugs on patient compliance with therapy.[

A cross-sectional study using data from the 2011 to 2014

Other studies examined the association between copayment amounts for adjuvant endocrine therapy, aromatase inhibitors, and tamoxifen and noncompliance in women with breast cancer.[

A cross-sectional survey study of adult patients (N = 300) receiving cancer therapy at Duke Cancer Institute found that 16% of patients reported high or overwhelming financial distress, 27% reported medication nonadherence, and 4.67% reported chemotherapy nonadherence.[

This study also found that an increased likelihood of nonadherence was associated with the following characteristics:

- Previous out-of-pocket cost discussion (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 2.58; 95% CI, 1.14–5.85).

- Higher financial burden than expected (adjusted OR, 2.90; 95% CI, 1.42–5.89).

- High financial distress (adjusted OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.38–1.96).

A statistically significant decreased risk of nonadherence was associated with having private insurance (adjusted OR, 0.31; 95% CI, 0.14–0.72).

A cross-sectional cohort study of 10,508 patients who started oral chemotherapy between 2007 and 2009 examined the association between prescription abandonment rates and cost sharing.[

Anecdotal reports also suggest that terminally ill cancer patients are foregoing the opportunity to obtain lethal doses of barbiturates in states with death-with-dignity laws because the price of these generic medications has increased to approximately $3,000 for a typical prescription.[

Quality of Life and Perceived Quality of Care

In a prospective, observational, population- and health care systems–based cohort study, the associations between financial burden, quality of life, and perceived quality of care were investigated using Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS) II data. Patient-reported health-related quality of life was measured using the EuroQol five-dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D).

From 2003 to 2006, patients were enrolled in the U.S. CanCORS study within 3 months of receiving either a colorectal or lung cancer diagnosis. For the CanCORS II study, among the surviving CanCORS patients, one disease-free subcohort and one advanced-disease subcohort were selected and resurveyed about their quality of life. The median time from diagnosis was 7.3 years. An adjusted structural equation modeling analysis found that higher financial distress was negatively associated with health-related quality of life (adjusted beta, -0.06 per burden category; 95% CI, -0.08 to -0.05); however, financial distress was not associated with perceived quality of care (OR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.93–1.29).[

Another cohort study using CanCORS data [

Several cross-sectional studies evaluated the impact of the financial burden of cancer care on patient quality of life. A survey analysis involving 149 patients with advanced-stage cancer in Texas at a public hospital (n = 72) and a comprehensive cancer center (n = 77) found that the median intensity of financial distress was double among patients treated in a public hospital compared with those treated in a comprehensive cancer center (on a scale of 0 = best to 10 = worst; 8 vs. 4; P = .0003).[

Another study analyzed answers to the question, "To what degree has cancer caused financial problems for you and your family?" Among 2,108 patients from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), those who responded "a lot" (8.6%) were more likely to report the following when compared with those who reported no financial burden:[

- Poor physical health (18.6% vs. 4.3%; P < .001).

- Poor mental health (8.3% vs. 1.8%; P < .001).

- Poor satisfaction with social activities and relationships (11.8% vs. 3.6%; P < .001).

- Less likely to report their quality of life as at least Good (adjusted OR, 9.24; 95% CI, 0.14–0.40).

Using the 2011 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data, one study [

- A lower Physical Component Score (beta, -2.45; 95% CI, -3.75 to -0.23).

- A lower Mental Component Score (beta, -3.05; 95% CI, -4.42 to -1.67).

- A greater likelihood of experiencing a depressed mood (adjusted OR, 1.95; 95% CI, 1.29–2.95).

- A greater likelihood of cancer recurrence–related worries (adjusted OR, 3.54; 95% CI, 2.65–4.72).

Satisfaction With Care

A review study documented that approximately 60% of people across a wide range of studies reported positive attitudes about cost-related discussions with their health care providers. Despite this finding, less than one-third of patients have had these discussions.[

Adverse Financial Events, Debt, and Bankruptcy

The impact of the financial burden of cancer care on adverse financial events, debt, and bankruptcy has been studied.[

One cross-sectional study, using the Livestrong 2012 survey data of 4,719 cancer survivors, reported that 63.8% of the survivors had worried about paying large bills related to cancer, 33.6% had gone into debt, 3.1% had filed for bankruptcy, and 39.7% had to make other kinds of financial sacrifices because of their cancer, its treatment, or the lasting effects of treatment.[

Furthermore, this study found that an increased likelihood of filing for bankruptcy was associated with the following characteristics of cancer patients:[

- Younger age (adjusted OR, 18–44 years, 1.81; 95% CI, 1.10–2.98; adjusted OR, 45–54 years, 1.86; 95% CI, 1.15–3.01; vs. 55–64 years).

- Lower household income (adjusted OR, ≤$40,000, 4.50; 95% CI, 2.56–7.93; adjusted OR, $41,000–$80,000, 2.80; 95% CI, 1.71–4.60; vs. ≥$80,000).

- Public health insurance (adjusted OR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.08–3.06; vs. private health insurance).

Similar patient characteristics were reported for those going into medical debt.[

A retrospective cohort study, using data from the 1995–2009 western Washington Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Cancer Registry–linked U.S. Bankruptcy Court for the Western District of Washington, found that patients with cancer diagnoses were more likely (hazard ratio [HR], 2.65; P < .05) to file for bankruptcy compared with patients without cancer.[

Another retrospective cohort study evaluated the risk of adverse financial events among patients with cancer. Investigators used data from the western Washington SEER Cancer Registry linked with TransUnion quarterly credit records, along with data from a control group selected from state voter registration records.[

A clearly worded grading system has been developed to identify different levels of financial toxicity.[

Impact on Caregivers

Informal cancer caregivers often share in the experience of financial toxicity by spending money on food, medications, and other patient needs in addition to taking time off from work to provide logistical, emotional, and medical support. In a recent survey of over 5,000 cancer patients whose caregivers were friends or family members, approximately 25% reported that their caregivers made significant employment changes after the cancer diagnosis, and 8% of survivors had caregivers who took at least 2 months of leave from work.[

Terminally ill cancer patients from households reporting financial hardship had a higher likelihood of receiving intensive life-prolonging care (defined as receiving ventilation or resuscitation to prolong life) than did those who did not report financial hardship (OR, 3.22; 95% CI, 1.38−7.53). In a longitudinal survey of 281 terminally ill cancer patients, 29% reported using most or all of their household's financial savings because of illness.[

Survival

In one retrospective cohort study, using data in the western Washington SEER Cancer Registry, cancer patients who filed for bankruptcy had an increased risk of mortality compared with those who did not file for bankruptcy (adjusted HR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.64–1.96).[

Internal and External Validity Concerns With Observational Studies

Data from randomized controlled trials offer the strongest evidence for establishing the efficacy of treatment on cancer outcomes. However, because cancer patients cannot ethically be subjected to financial toxicity through randomization, the current body of evidence is primarily from observational data, particularly from cross-sectional and cohort studies. Large nationally representative surveys provide the best estimates of the prevalence of certain conditions.

However, observational studies are prone to biases that may limit the validity of their findings. Several sources of bias are likely to be particularly important in observational studies assessing the association of financial toxicity with future outcomes, creating a challenge in interpreting the results of such studies.

In cross-sectional survey studies, high nonresponse rates may lead to possible nonresponse bias in reported estimates if the potential answers of nonrespondents vary from those who did respond. Another source of bias in survey research is reporting bias, which occurs when respondents reveal selective information that they believe is more socially desirable.

Another source of bias in observational studies is reverse causality, which may weaken any true association between financial toxicity and its potentially related outcomes. In one study,[

References:

- Dusetzina SB, Winn AN, Abel GA, et al.: Cost sharing and adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 32 (4): 306-11, 2014.

- Neugut AI, Subar M, Wilde ET, et al.: Association between prescription co-payment amount and compliance with adjuvant hormonal therapy in women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 29 (18): 2534-42, 2011.

- Zheng Z, Han X, Guy GP, et al.: Do cancer survivors change their prescription drug use for financial reasons? Findings from a nationally representative sample in the United States. Cancer 123 (8): 1453-1463, 2017.

- Farias AJ, Du XL: Association Between Out-Of-Pocket Costs, Race/Ethnicity, and Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy Adherence Among Medicare Patients With Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 35 (1): 86-95, 2017.

- Kim J, Rajan SS, Du XL, et al.: Association between financial burden and adjuvant hormonal therapy adherence and persistent use for privately insured women aged 18-64 years in BCBS of Texas. Breast Cancer Res Treat 169 (3): 573-586, 2018.

- Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, et al.: Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J Oncol Pract 10 (3): 162-7, 2014.

- Streeter SB, Schwartzberg L, Husain N, et al.: Patient and plan characteristics affecting abandonment of oral oncolytic prescriptions. J Oncol Pract 7 (3 Suppl): 46s-51s, 2011.

- Shankaran V, LaFrance RJ, Ramsey SD: Drug Price Inflation and the Cost of Assisted Death for Terminally Ill Patients-Death With Indignity. JAMA Oncol 3 (1): 15-16, 2017.

- Zafar SY, McNeil RB, Thomas CM, et al.: Population-based assessment of cancer survivors' financial burden and quality of life: a prospective cohort study. J Oncol Pract 11 (2): 145-50, 2015.

- Lathan CS, Cronin A, Tucker-Seeley R, et al.: Association of Financial Strain With Symptom Burden and Quality of Life for Patients With Lung or Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol 34 (15): 1732-40, 2016.

- Delgado-Guay M, Ferrer J, Rieber AG, et al.: Financial Distress and Its Associations With Physical and Emotional Symptoms and Quality of Life Among Advanced Cancer Patients. Oncologist 20 (9): 1092-8, 2015.

- Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al.: Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors' quality of life. J Oncol Pract 10 (5): 332-8, 2014.

- Kale HP, Carroll NV: Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer 122 (8): 283-9, 2016.

- Shih YT, Chien CR: A review of cost communication in oncology: Patient attitude, provider acceptance, and outcome assessment. Cancer 123 (6): 928-939, 2017.

- Jagsi R, Ward KC, Abrahamse PH, et al.: Unmet need for clinician engagement regarding financial toxicity after diagnosis of breast cancer. Cancer 124 (18): 3668-3676, 2018.

- Banegas MP, Guy GP, de Moor JS, et al.: For Working-Age Cancer Survivors, Medical Debt And Bankruptcy Create Financial Hardships. Health Aff (Millwood) 35 (1): 54-61, 2016.

- Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, et al.: Washington State cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood) 32 (6): 1143-52, 2013.

- Shankaran V, Li L, Fedorenko C, et al.: Risk of Adverse Financial Events in Patients With Cancer: Evidence From a Novel Linkage Between Cancer Registry and Credit Records. J Clin Oncol 40 (8): 884-891, 2022.

- Khera N: Reporting and grading financial toxicity. J Clin Oncol 32 (29): 3337-8, 2014.

- de Moor JS, Dowling EC, Ekwueme DU, et al.: Employment implications of informal cancer caregiving. J Cancer Surviv 11 (1): 48-57, 2017.

- Kent EE, Dionne-Odom JN: Population-Based Profile of Mental Health and Support Service Need Among Family Caregivers of Adults With Cancer. J Oncol Pract 15 (2): e122-e131, 2019.

- Shin JY, Lim JW, Shin DW, et al.: Underestimated caregiver burden by cancer patients and its association with quality of life, depression and anxiety among caregivers. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 27 (2): e12814, 2018.

- Ullrich A, Ascherfeld L, Marx G, et al.: Quality of life, psychological burden, needs, and satisfaction during specialized inpatient palliative care in family caregivers of advanced cancer patients. BMC Palliat Care 16 (1): 31, 2017.

- Shaffer KM, Kim Y, Carver CS, et al.: Effects of caregiving status and changes in depressive symptoms on development of physical morbidity among long-term cancer caregivers. Health Psychol 36 (8): 770-778, 2017.

- Rumpold T, Schur S, Amering M, et al.: Informal caregivers of advanced-stage cancer patients: Every second is at risk for psychiatric morbidity. Support Care Cancer 24 (5): 1975-1982, 2016.

- Litzelman K, Kent EE, Rowland JH: Social factors in informal cancer caregivers: The interrelationships among social stressors, relationship quality, and family functioning in the CanCORS data set. Cancer 122 (2): 278-86, 2016.

- Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, et al.: Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer 122 (13): 1987-95, 2016.

- Tucker-Seeley RD, Abel GA, Uno H, et al.: Financial hardship and the intensity of medical care received near death. Psychooncology 24 (5): 572-8, 2015.

- Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al.: Financial Insolvency as a Risk Factor for Early Mortality Among Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol 34 (9): 980-6, 2016.

Evidence Gaps and Areas for Future Research

Considering the conceptual framework for cancer and its impact on health care use, health outcomes, and financial effects, based on extant models, allows exploration of current evidence, gaps in evidence, and areas for future research.[

Risk Factors

Although many individual risk factors for financial hardship have been identified, the evidence that demonstrates the degree to which these factors contribute to the risk of later financial hardship is insufficient, as is information about the interplay between these factors and clinical factors at the time of diagnosis.

Specific areas in need of further study to address their influence on the risk of financial distress after a cancer diagnosis include the following:

- Preexisting debt.

- Prediagnosis conditions (i.e., overall comorbidity burden and the presence of specific illnesses).

- Types of employment (e.g., hourly vs. salaried).

- Asset levels.

Because ample evidence shows that financial distress occurs even among patients with health insurance, the role of different forms of insurance in protecting individuals from financial distress requires further study. Medicare may at least partially protect older people from financial harm. However, other factors associated with older age might also reduce the risk of financial distress, namely, retired adults typically have higher levels of assets (e.g., owning a home outright), pensions or retirement accounts, and Social Security. Another factor is that physicians may treat older patients less intensively and thus less expensively.

For adults of working age, characteristics of work-sponsored or individually purchased commercial insurance that vary from plan to plan—specifically, deductibles, copay levels, and coverage exclusions—may influence the risk of financial distress. These factors also warrant further study.

After patients are diagnosed with cancer and miss work during treatment, their ability to continue to work or return to work greatly influences their risk of financial hardship. Studies are needed that relate particular treatments, modalities of treatment (e.g., infusional therapy vs. oral therapy), and toxicities of treatments with work absenteeism, loss of productivity, and likelihood of returning to the workforce.

Implementation of the U.S. Affordable Care Act in 2008 provided a natural experiment to determine whether expanding access to health insurance for millions of Americans had an impact on rates of financial distress or insolvency for people with cancer. Proposed pilots for different Medicare payment systems may also offer opportunities for quasi-experimental approaches that compare implementation with nonimplementation.[

After diagnosis, treatment choice could, in theory, influence the likelihood of financial difficulties. For many cancers, guidelines include options that are considered equivalent therapeutically, yet the costs of the treatments might vary by 50-fold or more.[

Cancer management is unusual among medical interventions because it often involves intensive treatment at specialized facilities for weeks or months. For many patients, nonmedical costs associated with seeking treatment, such as the cost of transportation and lodging during treatment, can take a financial toll on families. The role that nonmedical costs play in financial hardship is an area in need of further study.

Financial Distress and Outcomes

Evidence from multiple retrospective studies shows that patients experiencing financial distress have reduced adherence to planned therapies, lower quality of life, and diminished survival. These studies have limitations because certain unmeasured clinical and financial factors that may influence treatment choice might also influence outcomes. Prospective or retrospective studies that include a more-comprehensive picture of financial status at diagnosis and clinical and patient factors that might influence treatment choice would provide a more accurate picture of the causal pathway between financial distress and outcomes.

Interventions Aimed at Reducing Financial Distress Among Cancer Patients

Several interventions specifically designed to reduce rates of financial distress among cancer patients have been proposed. Some are being implemented, but, to date, there have been no prospective studies evaluating the impact of these interventions on the rates and severity of financial distress, care choices, quality of life, or survival. Several of the most commonly discussed interventions are reviewed below.

Financial navigators

Financial navigators are being used in community and academic settings to help cancer patients avoid adverse financial consequences after a cancer diagnosis.[

- The impact of assessing risk factors for financial distress at diagnosis.

- Socioeconomic correlates of patients seeking and receiving financial counseling and assistance for their cancer care. Patient and family responsibility in relation to the offer of financial assistance for cancer care across different types of interventions and by different provider organizations needs to be better quantified.

- The impact of various types of financial information and assistance that are offered by care providers.

- The impact of counseling techniques to manage finances.

One prospective study (S1417CD [NCT02728804]), conducted in the National Cancer Institute Cooperative Cancer Clinical Trials Network, Implementation of a Prospective Financial Impact Assessment Tool in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer, evaluated the incidence of treatment-related financial hardship among patients with newly diagnosed metastatic colorectal cancer.[

Price transparency to facilitate treatment choice

Studies of price transparency initiatives, such as one that required California hospitals to publish their charges, have not found that they significantly influence patient treatment choice or pricing of goods and services by health care providers.[

More information is needed regarding how responsive cancer patients, their families, and/or their providers might be to offers of pricing transparency, direct or indirect financial assistance, or further reductions in out-of-pocket payment requirements.

Value-based pricing

Closely related to price transparency is the concept of value-based pricing, the idea that patients' out-of-pocket expenditures are tied to external assessment of value for competing therapies for particular conditions. The objective of value-based pricing is to steer patients to higher-value therapies through financial incentives (higher value = lower out-of-pocket responsibility). Although value-based pricing has been implemented for several clinical conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes), and evidence exists that this type of pricing increases the use of higher-value services, it has not been applied in oncology. Because of the ongoing transformation in how medical providers are paid for the care of cancer patients, there is a need study patient financial toxicity in the context of alternative payment models and quality measure reforms.

It is also unclear when in the care trajectory more information and financial assistance are needed and will be most effective in encouraging treatment initiation and continuance. For example, most employer-based insurance policies have an annual out-of-pocket maximum, beyond which the insurer assumes 100% of the cost of care. Many patients with late-stage cancer reach the maximum quickly, in which case the insurer bears the full cost of anticancer treatments for the remainder of the benefit year.

Health insurance reform

By providing millions of previously uninsured Americans with health insurance, the Massachusetts health insurance plan and the U.S. Affordable Care Act have presented an opportunity for natural pre-post experiments for health care policies that are aimed at reducing the financial exposure of an individual during severe illness. Because insurance appears to mitigate rather than eliminate the risk of financial distress from a cancer diagnosis and treatment, other interventions aimed at improving financial outcomes for insured people are likely needed.

Another policy targeting providers and patients would be to require the use of patient decision aids that include benefits-cost and financial-toxicity assessments and assistance through measures-of-quality for fee-for-service Medicare payments under Medicare Access and CHIP (Children's Health Insurance Program) Reauthorization Act (MACRA) legislation.[

Reducing and/or eliminating patient copayment/coinsurance for pathway-adherent cancer care in the fee-for-service Medicare program and/or commercial plans would also likely reduce patient and family financial burden across multiple treatment modalities—radiation, drugs, inpatient and outpatient coinsurance, and copayments.[

Cancer Treatment Costs References

Cancer treatment cost information can be difficult to access. Listed below are links to publicly available websites that contain updated information on costs related to cancer care:

-

Medicare Part B (office-administered) drug costs . -

Medicare benefits (includes information on deductibles and copayments).

References:

- Smith R, Clarke L, Berry K, et al.: A comparison of methods for linking health insurance claims with clinical records from a large cancer registry. [Abstract] Med Decis Making 21 (6): 530, 2001.

- Fay S, Hurst E, White MJ: The household bankruptcy decision. Am Econ Rev 92 (3): 706-18, 2002.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Oncology Care Model. Baltimore, Md: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2016.

Available online . Accessed December 8, 2016. - Ramsey S, Shankaran V: Managing the financial impact of cancer treatment: the role of clinical practice guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 10 (8): 1037-42, 2012.

- Conti RM, Bach PB: The 340B drug discount program: hospitals generate profits by expanding to reach more affluent communities. Health Aff (Millwood) 33 (10): 1786-92, 2014.

- Shankaran V; Southwest Oncology Group Cancer Care Delivery, Gastrointestinal Cancer: Implementation of a Prospective Financial Impact Assessment Tool in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. April 15, 2016.

- Kline RM, Bazell C, Smith E, et al.: Centers for medicare and medicaid services: using an episode-based payment model to improve oncology care. J Oncol Pract 11 (2): 114-6, 2015.

- Newcomer LN, Gould B, Page RD, et al.: Changing physician incentives for affordable, quality cancer care: results of an episode payment model. J Oncol Pract 10 (5): 322-6, 2014.

- Cutler DM: Payment reform is about to become a reality. JAMA 313 (16): 1606-7, 2015.

- Press MJ, Rajkumar R, Conway PH: Medicare's New Bundled Payments: Design, Strategy, and Evolution. JAMA 315 (2): 131-2, 2016.

- Howard DH: Drug companies' patient-assistance programs--helping patients or profits? N Engl J Med 371 (2): 97-9, 2014.

Latest Updates to This Summary (05 / 29 / 2024)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Added

This summary is written and maintained by the

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the treatment of cancer and financial toxicity. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Financial Toxicity and Cancer Treatment are:

- Stacie B. Dusetzina, PhD (Vanderbilt University School of Medicine)

- Scott D. Ramsey, MD, PhD (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center)

- Veena Shankaran, MD, MS (Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center & University of Washington)

- K. Robin Yabroff, PhD (American Cancer Society)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Adult Treatment Editorial Board uses a

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Financial Toxicity and Cancer Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at:

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in

Disclaimer

Based on the strength of the available evidence, treatment options may be described as either "standard" or "under clinical evaluation." These classifications should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our

Last Revised: 2024-05-29

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the

Healthwise, Healthwise for every health decision, and the Healthwise logo are trademarks of Ignite Healthwise, LLC.

Page Footer

I want to...

Audiences

Secure Member Sites

The Cigna Group Information

Disclaimer

Individual and family medical and dental insurance plans are insured by Cigna Health and Life Insurance Company (CHLIC), Cigna HealthCare of Arizona, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Illinois, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Georgia, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of North Carolina, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of South Carolina, Inc., and Cigna HealthCare of Texas, Inc. Group health insurance and health benefit plans are insured or administered by CHLIC, Connecticut General Life Insurance Company (CGLIC), or their affiliates (see

All insurance policies and group benefit plans contain exclusions and limitations. For availability, costs and complete details of coverage, contact a licensed agent or Cigna sales representative. This website is not intended for residents of New Mexico.