Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage

Plans through your employer

Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

Learn

Living or working abroad?

Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer (PDQ®): Genetics - Health Professional Information [NCI]

Introduction

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) is characterized by the presence of one or more of the following: cutaneous leiomyomas (or leiomyomata), uterine leiomyomas (fibroids) in females, and renal cell cancer (RCC). Germline pathogenic variants in the FHgene are responsible for the susceptibility to HLRCC. FH encodes fumarate hydratase, the enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of fumarate to malate in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (Krebs cycle).

Nomenclature

Historically, the predisposition to the development of cutaneous leiomyomas was referred to as multiple cutaneous leiomyomatosis. In 1973, two kindreds were described in which multiple members over three generations exhibited cutaneous leiomyomas and uterine leiomyomas and/or leiomyosarcomas inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern.[

References:

- Reed WB, Walker R, Horowitz R: Cutaneous leiomyomata with uterine leiomyomata. Acta Derm Venereol 53 (5): 409-16, 1973.

- Launonen V, Vierimaa O, Kiuru M, et al.: Inherited susceptibility to uterine leiomyomas and renal cell cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 (6): 3387-92, 2001.

Genetics

FHGene

The FHgene consists of ten exons encompassing 22.15 kb of DNA. The gene is highly conserved across species. The human FH gene is located on chromosome 1q42.3-43.

Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) is an autosomal dominant syndrome. An individual can be predisposed to HLRCC disease manifestations when he/she inherits a heterozygous pathogenic variant in the FH gene.[

Renal tumors that develop in individuals who inherit a germline pathogenic variant in FH typically display a loss of heterozygosity because of a second somatic FH variant. This finding suggests that loss of function of the fumarate hydratase protein is the basis for tumor formation in HLRCC and supports a tumor suppressor function for FH.[

Inherited biallelic pathogenic variants in the FH gene (homozygous or compound heterozygous) can cause autosomal recessive fumarate hydratase deficiency (FHD) (also abbreviated as FMRD), a disorder characterized by rapid, progressive neonatal neurological impairment that includes hypotonia, seizures, and cerebral atrophy. For more information, see the

Prevalence

Prevalence estimates for HLRCC are evolving. Older estimates suggested a prevalence of 1 in 200,000 individuals.[

Penetrance ofFHPathogenic Variants

On the basis of the observation that most patients with HLRCC have at least one of the three major clinical manifestations, the penetrance of HLRCC in carriers of pathogenic FH variants appears to be very high. However, the estimated cumulative lifetime incidence of renal cell cancer (RCC) varies widely, with most estimates ranging from 15% to 30% in families with germline FH pathogenic variants, depending on ascertainment method and the imaging modalities used.[

A study that analyzed patients undergoing cancer genetic testing suggested that RCC may be more common in males with HLRCC than in females with HLRCC.[

Genotype-Phenotype Correlations

Correlations between specific FH variants and the occurrence of cutaneous/uterine leiomyomas, RCC, or other primary features of HLRCC have not been reported.[

However, certain FH variants (primarily missense variants) seem to be associated with an increased risk for paraganglioma (PGL)/pheochromocytoma (PHEO) in the absence of other HLRCC features.[

Sequence Analysis

Using bidirectional DNA sequencing methodology, pathogenic variants in FH have been detected in more than 85% of individuals with HLRCC.[

Genetically Related Disorders

Fumarate hydratase deficiency (fumaric aciduria, FHD)

FHD (also abbreviated as FMRD) is an autosomal recessive disorder that results from the inheritance of biallelic pathogenic variants in the FH gene. This inborn error of metabolism is characterized by rapid, progressive neurological impairment that includes hypotonia, seizures, and cerebral atrophy. Homozygous or compound heterozygous germline pathogenic variants in FH are found in individuals with FHD.[

Four FH variants are thought to be associated with FHD: (1) p.Lys477dup, (2) p.Pro174Arg, (3) p.Gln376Pro, and (4) p.Ala308Gly.[

While multiple studies have demonstrated that certain biallelic FH pathogenic variants can cause autosomal recessive FHD, these variants are not associated with HLRCC when in the heterozygous state.[

SomaticFHvariants

Biallelic somatic loss of FH has been identified in two early-onset sporadic uterine leiomyomas and a soft tissue sarcoma of the lower limb without other associated tumor characteristics of the heritable disease.[

References:

- Alam NA, Rowan AJ, Wortham NC, et al.: Genetic and functional analyses of FH mutations in multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis, hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cancer, and fumarate hydratase deficiency. Hum Mol Genet 12 (11): 1241-52, 2003.

- Tomlinson IP, Alam NA, Rowan AJ, et al.: Germline mutations in FH predispose to dominantly inherited uterine fibroids, skin leiomyomata and papillary renal cell cancer. Nat Genet 30 (4): 406-10, 2002.

- Toro JR, Nickerson ML, Wei MH, et al.: Mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene cause hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families in North America. Am J Hum Genet 73 (1): 95-106, 2003.

- Wei MH, Toure O, Glenn GM, et al.: Novel mutations in FH and expansion of the spectrum of phenotypes expressed in families with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. J Med Genet 43 (1): 18-27, 2006.

- Bayley JP, Launonen V, Tomlinson IP: The FH mutation database: an online database of fumarate hydratase mutations involved in the MCUL (HLRCC) tumor syndrome and congenital fumarase deficiency. BMC Med Genet 9: 20, 2008.

- Vocke CD, Ricketts CJ, Merino MJ, et al.: Comprehensive genomic and phenotypic characterization of germline FH deletion in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 56 (6): 484-492, 2017.

- Launonen V, Vierimaa O, Kiuru M, et al.: Inherited susceptibility to uterine leiomyomas and renal cell cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 (6): 3387-92, 2001.

- Forde C, Lim DHK, Alwan Y, et al.: Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer: Clinical, Molecular, and Screening Features in a Cohort of 185 Affected Individuals. Eur Urol Oncol 3 (6): 764-772, 2020.

- Shuch B, Li S, Risch H, et al.: Estimation of the carrier frequency of fumarate hydratase alterations and implications for kidney cancer risk in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cancer. Cancer 126 (16): 3657-3666, 2020.

- Lu E, Hatchell KE, Nielsen SM, et al.: Fumarate hydratase variant prevalence and manifestations among individuals receiving germline testing. Cancer 128 (4): 675-684, 2022.

- Alam NA, Olpin S, Leigh IM: Fumarate hydratase mutations and predisposition to cutaneous leiomyomas, uterine leiomyomas and renal cancer. Br J Dermatol 153 (1): 11-7, 2005.

- Pfaffenroth EC, Linehan WM: Genetic basis for kidney cancer: opportunity for disease-specific approaches to therapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther 8 (6): 779-90, 2008.

- Grubb RL, Franks ME, Toro J, et al.: Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: a syndrome associated with an aggressive form of inherited renal cancer. J Urol 177 (6): 2074-9; discussion 2079-80, 2007.

- Abou Alaiwi S, Nassar AH, Adib E, et al.: Trans-ethnic variation in germline variants of patients with renal cell carcinoma. Cell Rep 34 (13): 108926, 2021.

- Zavoshi S, Lu E, Boutros PC, et al.: Fumarate Hydratase Variants and Their Association With Paraganglioma/Pheochromocytoma. Urology 176: 106-114, 2023.

- Alam NA, Barclay E, Rowan AJ, et al.: Clinical features of multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis: an underdiagnosed tumor syndrome. Arch Dermatol 141 (2): 199-206, 2005.

- Coughlin EM, Christensen E, Kunz PL, et al.: Molecular analysis and prenatal diagnosis of human fumarase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab 63 (4): 254-62, 1998.

- Bourgeron T, Chretien D, Poggi-Bach J, et al.: Mutation of the fumarase gene in two siblings with progressive encephalopathy and fumarase deficiency. J Clin Invest 93 (6): 2514-8, 1994.

- Badeloe S, Frank J: Clinical and molecular genetic aspects of hereditary multiple cutaneous leiomyomatosis. Eur J Dermatol 19 (6): 545-51, 2009 Nov-Dec.

- Kamihara J, Horton C, Tian Y, et al.: Different Fumarate Hydratase Gene Variants Are Associated With Distinct Cancer Phenotypes. JCO Precis Oncol 5: 1568-1578, 2021.

- Kiuru M, Lehtonen R, Arola J, et al.: Few FH mutations in sporadic counterparts of tumor types observed in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer families. Cancer Res 62 (16): 4554-7, 2002.

- Lehtonen R, Kiuru M, Vanharanta S, et al.: Biallelic inactivation of fumarate hydratase (FH) occurs in nonsyndromic uterine leiomyomas but is rare in other tumors. Am J Pathol 164 (1): 17-22, 2004.

- Linehan WM, Spellman PT, Ricketts CJ, et al.: Comprehensive Molecular Characterization of Papillary Renal-Cell Carcinoma. N Engl J Med 374 (2): 135-45, 2016.

Molecular Biology

The mechanisms by which alterations in FH lead to hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) are currently under investigation. Biallelic inactivation of FH has been shown to result in loss of oxidative phosphorylation and reliance on aerobic glycolysis to meet cellular energy requirements. Interruption of the Krebs cycle because of reduced or absent fumarate hydratase activity results in increased levels of intracellular fumarate. This increase inhibits the activity of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) prolyl hydroxylases, resulting in the accumulation of HIF-alpha.[

References:

- Isaacs JS, Jung YJ, Mole DR, et al.: HIF overexpression correlates with biallelic loss of fumarate hydratase in renal cancer: novel role of fumarate in regulation of HIF stability. Cancer Cell 8 (2): 143-53, 2005.

- Pollard PJ, Brière JJ, Alam NA, et al.: Accumulation of Krebs cycle intermediates and over-expression of HIF1alpha in tumours which result from germline FH and SDH mutations. Hum Mol Genet 14 (15): 2231-9, 2005.

- Sudarshan S, Sourbier C, Kong HS, et al.: Fumarate hydratase deficiency in renal cancer induces glycolytic addiction and hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1alpha stabilization by glucose-dependent generation of reactive oxygen species. Mol Cell Biol 29 (15): 4080-90, 2009.

- Pollard P, Wortham N, Barclay E, et al.: Evidence of increased microvessel density and activation of the hypoxia pathway in tumours from the hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer syndrome. J Pathol 205 (1): 41-9, 2005.

- Alderson NL, Wang Y, Blatnik M, et al.: S-(2-Succinyl)cysteine: a novel chemical modification of tissue proteins by a Krebs cycle intermediate. Arch Biochem Biophys 450 (1): 1-8, 2006.

- Ooi A, Wong JC, Petillo D, et al.: An antioxidant response phenotype shared between hereditary and sporadic type 2 papillary renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell 20 (4): 511-23, 2011.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical characteristics of hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) include cutaneous leiomyomas, uterine leiomyomas (fibroids), and renal cell cancer (RCC). Affected individuals may have multiple cutaneous leiomyomas, a single skin leiomyoma, or no cutaneous lesion; an RCC that is typically solitary, or no renal tumors; and/or uterine leiomyomas. HLRCC is phenotypically variable; disease severity shows significant intrafamilial and interfamilial variation.[

Cutaneous Leiomyomas

Cutaneous leiomyomas present as firm papules or nodules that appear pink or reddish-brown. These lesions usually appear on the trunk, on the extremities, and occasionally on the face. These lesions occur at a mean age of 25 years (age range, 10–47 y) and often increase in size and number with age. Lesions are sensitive to light touch and/or cold temperature. They can also be painful. Pain is correlated with severity of cutaneous involvement.[

Uterine Leiomyomas

The onset of uterine leiomyomas in women with HLRCC occurs at a younger age than in women in the general population. The age at diagnosis ranges from 18 to 63 years (mean age, 30 y). One series reported uterine leiomyomas in 18 of 29 women (62%) with a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant in FH; the ages of the women ranged from 24 to 63 years.[

Renal Cell Cancers (RCCs)

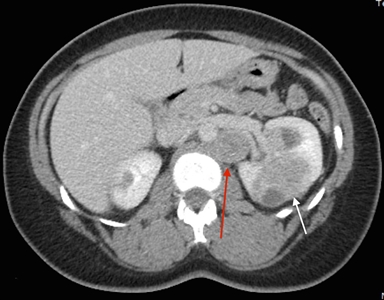

The symptoms of RCC may include hematuria, lower back pain, and a palpable mass. However, a large number of individuals with RCC are asymptomatic. Furthermore, not all individuals with HLRCC present with or develop RCC. Most RCCs are unilateral and solitary; in a few individuals, they are multifocal. The exact incidence of RCC in affected individuals remains to be determined, and widely varying estimates have been provided by different groups (1%–60%).[

Figure 1. Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer–associated renal tumors are commonly unilateral and solitary; in a few individuals, they are multifocal. Red arrow indicates a retroperitoneal lymph node. White arrow indicates a left renal mass.

Uterine Leiomyosarcomas

It is unclear whether women with HLRCC have a higher risk of developing uterine leiomyosarcomas than women of similar age in the general population. In the original description of HLRCC, it was reported that 2 of 11 women with uterine leiomyomas also had a uterine leiomyosarcoma, a cancer that may be clinically aggressive if not detected and treated at an early stage.[

Other Manifestations

Four FH-positive cases with breast cancer, one case of bladder cancer, and one case of bilateral macronodular adrenocortical disease with Cushing syndrome have been reported. A series from the NCI found that 20 of 255 patients (7.8%) with HLRCC had adrenal nodules, some of which did not appear to be adenomas based on imaging characteristics. Resections were performed on many of these lesions since they were fluorodeoxyglucose avid. All of the lesions showed evidence of both micronodular and macronodular adrenal hyperplasia, suggesting that adrenal nodules could be an additional manifestation of HLRCC.[

References:

- Wei MH, Toure O, Glenn GM, et al.: Novel mutations in FH and expansion of the spectrum of phenotypes expressed in families with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. J Med Genet 43 (1): 18-27, 2006.

- Launonen V, Vierimaa O, Kiuru M, et al.: Inherited susceptibility to uterine leiomyomas and renal cell cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 (6): 3387-92, 2001.

- Toro JR, Nickerson ML, Wei MH, et al.: Mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene cause hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families in North America. Am J Hum Genet 73 (1): 95-106, 2003.

- Bhola PT, Gilpin C, Smith A, et al.: A retrospective review of 48 individuals, including 12 families, molecularly diagnosed with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC). Fam Cancer 17 (4): 615-620, 2018.

- Farquhar CM, Steiner CA: Hysterectomy rates in the United States 1990-1997. Obstet Gynecol 99 (2): 229-34, 2002.

- Alam NA, Barclay E, Rowan AJ, et al.: Clinical features of multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis: an underdiagnosed tumor syndrome. Arch Dermatol 141 (2): 199-206, 2005.

- Stewart L, Glenn GM, Stratton P, et al.: Association of germline mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene and uterine fibroids in women with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. Arch Dermatol 144 (12): 1584-92, 2008.

- Muller M, Ferlicot S, Guillaud-Bataille M, et al.: Reassessing the clinical spectrum associated with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome in French FH mutation carriers. Clin Genet 92 (6): 606-615, 2017.

- Shuch B, Vourganti S, Ricketts CJ, et al.: Defining early-onset kidney cancer: implications for germline and somatic mutation testing and clinical management. J Clin Oncol 32 (5): 431-7, 2014.

- Wong MH, Tan CS, Lee SC, et al.: Potential genetic anticipation in hereditary leiomyomatosis-renal cell cancer (HLRCC). Fam Cancer 13 (2): 281-9, 2014.

- Forde C, Lim DHK, Alwan Y, et al.: Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer: Clinical, Molecular, and Screening Features in a Cohort of 185 Affected Individuals. Eur Urol Oncol 3 (6): 764-772, 2020.

- Grubb RL, Franks ME, Toro J, et al.: Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: a syndrome associated with an aggressive form of inherited renal cancer. J Urol 177 (6): 2074-9; discussion 2079-80, 2007.

- Linehan WM, Bratslavsky G, Pinto PA, et al.: Molecular diagnosis and therapy of kidney cancer. Annu Rev Med 61: 329-43, 2010.

- Lehtonen HJ, Kiuru M, Ylisaukko-Oja SK, et al.: Increased risk of cancer in patients with fumarate hydratase germline mutation. J Med Genet 43 (6): 523-6, 2006.

- Ylisaukko-oja SK, Kiuru M, Lehtonen HJ, et al.: Analysis of fumarate hydratase mutations in a population-based series of early onset uterine leiomyosarcoma patients. Int J Cancer 119 (2): 283-7, 2006.

- Shuch B, Ricketts CJ, Vocke CD, et al.: Adrenal nodular hyperplasia in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. J Urol 189 (2): 430-5, 2013.

- Matyakhina L, Freedman RJ, Bourdeau I, et al.: Hereditary leiomyomatosis associated with bilateral, massive, macronodular adrenocortical disease and atypical cushing syndrome: a clinical and molecular genetic investigation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90 (6): 3773-9, 2005.

- Clark GR, Sciacovelli M, Gaude E, et al.: Germline FH mutations presenting with pheochromocytoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99 (10): E2046-50, 2014.

Histopathology

Cutaneous Leiomyomas

Cutaneous leiomyomas are believed to arise from the arrectores pilorum muscles attached to the hair follicles. Histologically, these are dermal tumors that spare the epidermis. Morphologically, these tumors have interlacing smooth muscle fibers interspersed with collagen fibers.[

Uterine Leiomyomas

A review of the National Cancer Institute's experience with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC)-associated uterine leiomyomas reported that most of these cases were well-circumscribed fascicular tumors with occasional cases showing increased cellularity and atypia. The hallmark feature of these cases was similar to those observed in HLRCC kidney cancer: the presence of orangeophilic, prominent nucleoli that are surrounded by a perinuclear halo. While some cases had atypical features, no cases had tumor necrosis or atypical mitosis suggestive of malignancy or leiomyosarcoma.[

RCC

The renal cell cancers (RCCs) associated with HLRCC have unique histological features, including the presence of cells with abundant amphophilic cytoplasm and large nuclei with large inclusion-like eosinophilic nucleoli. These cytologic features were attributed to type 2 papillary tumors in the original description.[

References:

- Fearfield LA, Smith JR, Bunker CB, et al.: Association of multiple familial cutaneous leiomyoma with a uterine symplastic leiomyoma. Clin Exp Dermatol 25 (1): 44-7, 2000.

- Sanz-Ortega J, Vocke C, Stratton P, et al.: Morphologic and molecular characteristics of uterine leiomyomas in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cancer (HLRCC) syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 37 (1): 74-80, 2013.

- Launonen V, Vierimaa O, Kiuru M, et al.: Inherited susceptibility to uterine leiomyomas and renal cell cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 (6): 3387-92, 2001.

- Wei MH, Toure O, Glenn GM, et al.: Novel mutations in FH and expansion of the spectrum of phenotypes expressed in families with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. J Med Genet 43 (1): 18-27, 2006.

- Merino MJ, Torres-Cabala C, Pinto P, et al.: The morphologic spectrum of kidney tumors in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC) syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 31 (10): 1578-85, 2007.

- Merino MJ, Torres-Cabala CA, Zbar B, et al.: Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma syndrome (HLRCC): Clinical histopathological and molecular features of the first American families described. [Abstract] Mod Pathol 16 (Suppl): A-739, 162A, 2003.

Management

Diagnosis and Testing

Genetic testing for the FHgene is clinically available and performed by Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified laboratories. FH currently is the only gene known to be associated with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC). Most patients with HLRCC have a germline pathogenic variant in FH.

Because the genetic analysis of HLRCC is complex, any interpretation of a variant of unknown significance result needs to be performed with consultation by clinical cancer geneticists, ideally in a center that has significant experience with this disease.

Clinical diagnosis

There is no current consensus on the diagnostic criteria for HLRCC.[

Some experts suggest that a clinical dermatologic diagnosis of HLRCC requires one of the following:[

- Multiple cutaneous leiomyomas with at least one histologically confirmed leiomyoma.

- A single leiomyoma in the presence of a positive family history of HLRCC.

More recent comprehensive criteria for diagnosis have been suggested and are often used by experts in the field. Suggested criteria include dermatologic manifestations like multiple cutaneous leiomyomas (histologically confirmed). At least two of the following manifestations must also be present:[

- Surgical treatment for symptomatic uterine leiomyomas before age 40 years.

- A diagnosis of type 2 papillary RCC before age 40 years (now referred to as FH-deficient papillary RCC).

- A first-degree relative who meets one of these criteria.

Since FH-deficient RCC can resemble collecting duct RCC, the presence of FH-deficient RCC before age 40 years has been suggested as an additional criterion.[

Differential diagnosis

Cutaneous lesions

Cutaneous leiomyomas are rare. The detection of multiple lesions is specific to HLRCC. Because leiomyomas are clinically similar to various cutaneous lesions, histological diagnosis is required to objectively prove the nature of the lesion.

Uterine leiomyomas

Uterine leiomyoma is the most common benign pelvic tumor in women in the general population. Most uterine leiomyomas are sporadic and nonsyndromic.[

RCCs

Diagnostic clues of HLRCC may rely on the presence of several phenotypic features in different organs (cutaneous, uterine, and renal). One or more of these characteristic features may be present in the patient or in one or more of their affected biologic relatives.

Although familial RCCs are associated with rather specific renal pathology, the rarity of these syndromes results in few pathologists gaining sufficient experience to recognize their histological features.

The differential diagnoses may include other rare familial RCC syndromes with specific renal pathology, including:

- Hereditary papillary renal carcinoma (HPRC). Predisposition to papillary RCC (formerly known as type 1 papillary RCC). Inheritance is autosomal dominant.[

8 ] - Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome (BHD). A spectrum of renal tumors including renal oncocytoma (benign), chromophobe renal cell cancer (malignant), and a combination of both cell types (so-called oncocytic hybrid tumor).[

9 ] Individuals with BHD can present with cutaneous fibrofolliculomas /trichodiscomas and/or with multiple lung cysts and spontaneous pneumothorax. Inheritance is autosomal dominant.[10 ,11 ]

Genetic testing

Genetic testing is used clinically for diagnostic confirmation of at-risk individuals. It is recommended that both pretest and posttest genetic counseling be offered to persons contemplating germline pathogenic variant testing.[

Testing strategy

Genetic testing for a germline FH pathogenic variant is indicated for all individuals with HLRCC and for all individuals who are suspected of having HLRCC, regardless of family history. This includes individuals with cutaneous leiomyomas, as described in the

Risk to family members

HLRCC is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner.[

Parents of a proband

- Some individuals diagnosed with HLRCC have an affected parent, while others have unaffected parents, suggesting that some individuals have HLRCC as the result of a de novo pathogenic variant or parental mosaicism.

- The proportion of cases caused by de novo pathogenic variants is unknown, as subtle manifestations in parents have not been systematically evaluated; similarly, not all unaffected parents have undergone FH testing.

- Evaluation of parents of a proband with a suspected de novo pathogenic variant may include genetic testing if the FH disease-causing variant in the proband has been identified.

Although some individuals diagnosed with HLRCC have an affected parent, the family history may appear to be negative because of limited family history, failure to recognize the disorder in family members, early death of the affected parent before the onset of syndrome-related symptoms, or late onset of the disease in the affected parent.[

Siblings of a proband

- The risk to the siblings of the proband depends upon the genetic status of the proband's parents.

- If a parent of a proband is clinically affected or has a disease-causing variant, each sibling of the proband is at a 50% risk of inheriting the variant.

- If the disease-causing variant cannot be detected in the DNA of either parent, the risk to siblings is low. However, risk will be greater than that of the general population because there is a possibility of germline mosaicism.

Testing of at-risk family members

Use of genetic testing for early identification of at-risk family members improves diagnostic certainty. It reduces the number of unnecessary costly and stressful screening procedures in at-risk members who have not inherited their family's disease-causing variant.[

Early recognition of clinical manifestations may allow timely intervention, which could, in theory, improve outcome. Therefore, clinical surveillance of asymptomatic at-risk relatives for early RCC detection is reasonable, but additional objective data regarding the impact of screening on syndrome-related mortality are needed.

Related genetic counseling issues

Predicting the phenotype in individuals who have inherited a pathogenic variant

It is not possible to predict whether HLRCC-related symptoms will occur or, if they do, what the age at onset, type, severity, or clinical characteristics will be in individuals who have a pathogenic variant. In an in-depth characterization of clinical and genetic features analyzed within 21 new families, the phenotypes displayed a wide range of clinical presentations and no apparent genotype -phenotype correlations were found.[

When neither parent of a proband with an autosomal dominant condition has the disease-causing variant or clinical evidence of the disorder, it is likely that the proband has a de novo pathogenic variant. However, nonmedical explanations include the possibility of alternate paternity or undisclosed adoption. Genetic testing of at-risk family members is appropriate in order to identify the need for continued lifelong clinical surveillance. Interpretation of the pathogenic variant test result is most accurate when a disease-causing variant has been identified in an affected family member. Those who have a disease-causing variant are recommended to undergo lifelong periodic surveillance. Meanwhile, family members and offspring who have not inherited the pathogenic variant are thought to have RCC risks similar to those in the general population; no special management of these individuals is recommended.

Early detection of at-risk individuals affects medical management

Screening for early disease manifestations in HLRCC is an important aspect of clinical care of affected individuals. Although there are no prospective studies comparing specific renal cancer screening practices, the aggressive nature of HLRCC-associated RCC [

Uterine fibroids often cause significant symptoms related to bleeding and the presence of a large mass, but small fibroids may be asymptomatic. As HLRCC fibroids can lead to hysterectomies and loss of the ability to bear children in affected young women, the goal of screening in women interested in preserving fertility is to limit some of these irreversible complications. Although there are no specific management recommendations related to HLRCC-associated fibroids, various management strategies have proven effective in the treatment of sporadic fibroids. These strategies include use of hormonal therapies, pain medications, percutaneous and endovascular procedures, and surgical options. Early referral to a fertility specialist may be useful to assist with family planning.

Surveillance

It has been suggested that individuals with a suspected or confirmed diagnosis of HLRCC, individuals with heterozygous pathogenic variants in FH regardless of clinical manifestations, and at-risk family members who have not undergone genetic testing undertake the following regular surveillance, performed by physicians familiar with the clinical manifestations of HLRCC.

- Skin. There are some published recommendations to perform skin exams on a regular basis, but there is no consensus regarding frequency of skin exams, and recommendations have not been prospectively validated.

- Uterine. For women with an intact uterus, annual gynecologic consultation is recommended, accompanied by periodic imaging. Imaging may include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis or ultrasound to assess the severity of uterine leiomyomas and to search for changes suggestive of developing leiomyosarcoma.[

6 ,7 ,16 ,22 ] - Paraganglioma (PGL)/Pheochromocytoma (PHEO). Although PGL/PHEO surveillance is not included in suggested HLRCC guidelines, one study suggested that surveillance similar to that which is recommended for SDHx carriers could be considered for individuals with unique FH variants associated with increased PGL/PHEO risk (i.e., p.Thr234Ala, p.Ala273Thr, and p.Ala194Thr).[

23 ] This surveillance regimen includes annual biochemical screening (urine or plasma metanephrines), careful physical exam with a focus on the neck and abdominal areas, and whole-body cross-sectional imaging. - Renal. In view of the aggressive nature of this disease, annual imaging with either computed tomography (CT) scan with contrast or MRI with gadolinium is warranted even if the initial (baseline) evaluation reveals normal kidneys. Special attention to imaging is warranted in this population because subtle findings, such as a complex cyst, may sometimes represent an aggressive malignancy. The age to initiate renal screening is uncertain, however, because HLRCC has been described in children as young as 10 years. The

HLRCC Family Alliance recommends annual imaging beginning at age 8 years in children at risk of HLRCC and those with HLRCC.[1 ] MRI has the advantage of sparing the patient radiation exposure and for this reason it may be preferred over CT for lifetime surveillance of HLRCC patients.Any suspicious renal lesion (indeterminate, questionable, or complex cysts) at a previous examination should be closely followed with periodic imaging, preferably using the same modality to allow for comparisons. The use of renal ultrasound examination may be helpful in the characterization of cystic lesions identified on cross-sectional imaging. It should be cautioned that ultrasound examination alone is never sufficient. Renal tumors should be evaluated by a clinician familiar with HLRCC-related renal cancer.[

10 ,24 ]Because of the aggressive growth of these tumors, patients warrant regular surveillance with a low threshold for early surgical intervention for solid renal lesions. This strategy differs from that described for several other hereditary RCC syndromes, in which the tumor behavior is more indolent, and for which observation may be a viable option.[

10 ,24 ,25 ]

Level of evidence (skin surveillance): 5

Level of evidence (uterine surveillance): 4

Level of evidence (renal surveillance): 4

Treatment of Manifestations

Cutaneous lesions

Cutaneous leiomyomas are most appropriately examined by a dermatologist. Generally, asymptomatic cutaneous leiomyomas require no treatment. Treatment of symptomatic cutaneous leiomyomas may be difficult if a patient has diffuse disease in a wide distribution. Surgical excision may be performed for a solitary painful lesion. Lesions can be treated by cryoablation and/or lasers. Several medications, including calcium channel blockers, alpha blockers, nitroglycerin, antidepressants, and antiepileptic drugs, reportedly reduce leiomyoma-related pain.[

Level of evidence: 5

Uterine leiomyomas

Uterine leiomyomas are best evaluated by a gynecologist. HLRCC-associated leiomyomas are treated in the same manner as sporadic leiomyomas. However, because of the multiplicity, size, and potential rapid growth observed in HLRCC-related uterine leiomyomas, most women may require medical and/or surgical intervention earlier and more often than would be expected in the general population. Medical therapy (currently including gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, anti-hormonal medications, and pain relievers) may be used to initially treat uterine leiomyomas, both to decrease their size in preparation for surgical removal and to provide temporary relief from leiomyoma-related pain. When women desire fertility preservation, myomectomy can be used to remove leiomyomas and simultaneously preserve the uterus. Hysterectomy should be performed only when necessary.[

Level of evidence: 4

RCCs

Efforts aimed at early detection of HLRCC-related RCC are prudent, given its biological aggressiveness. However, studies do not currently show that early detection is clearly associated with improved survival. Surgical excision of these malignancies at the first sign of disease is recommended, unlike management of other hereditary cancer syndromes. The propensity for lymph node involvement, even with small renal tumors, may necessitate a lymph node dissection for more appropriate staging.[

Level of evidence: 4

Therapies under investigation

It has been suggested that hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF1)-alpha overexpression is involved in HLRCC tumorigenesis.[

Loss of oxidative phosphorylation resulting from biallelic inactivation of FH renders HLRCC tumors almost entirely reliant on aerobic glycolysis for meeting cellular adenosine triphosphate and other bioenergetics requirements. Consequently, targeting aerobic glycolysis is being explored as a therapeutic strategy.[

Other investigations [

General information about clinical trials is also available from the

References:

- HLRCC Family Alliance: The HLRCC Handbook. Version 2.0. Boston, MA: HLRCC Family Alliance, 2013.

Available online . Last accessed November 6, 2024. - Schmidt LS, Linehan WM: Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis 7: 253-60, 2014.

- Smit DL, Mensenkamp AR, Badeloe S, et al.: Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families referred for fumarate hydratase germline mutation analysis. Clin Genet 79 (1): 49-59, 2011.

- Menko FH, Maher ER, Schmidt LS, et al.: Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC): renal cancer risk, surveillance and treatment. Fam Cancer 13 (4): 637-44, 2014.

- Lehtonen HJ: Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: update on clinical and molecular characteristics. Fam Cancer 10 (2): 397-411, 2011.

- Toro JR, Nickerson ML, Wei MH, et al.: Mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene cause hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families in North America. Am J Hum Genet 73 (1): 95-106, 2003.

- Stewart L, Glenn GM, Stratton P, et al.: Association of germline mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene and uterine fibroids in women with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. Arch Dermatol 144 (12): 1584-92, 2008.

- Zbar B, Tory K, Merino M, et al.: Hereditary papillary renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 151 (3): 561-6, 1994.

- Pavlovich CP, Walther MM, Eyler RA, et al.: Renal tumors in the Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 26 (12): 1542-52, 2002.

- Linehan WM, Bratslavsky G, Pinto PA, et al.: Molecular diagnosis and therapy of kidney cancer. Annu Rev Med 61: 329-43, 2010.

- Schmidt LS, Linehan WM: Molecular genetics and clinical features of Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome. Nat Rev Urol 12 (10): 558-69, 2015.

- Riley BD, Culver JO, Skrzynia C, et al.: Essential elements of genetic cancer risk assessment, counseling, and testing: updated recommendations of the National Society of Genetic Counselors. J Genet Couns 21 (2): 151-61, 2012.

- Update: information about obtaining a CLIA certificate. Jt Comm Perspect 26 (12): 6-7, 2006.

- Kopp RP, Stratton KL, Glogowski E, et al.: Utility of prospective pathologic evaluation to inform clinical genetic testing for hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma. Cancer 123 (13): 2452-2458, 2017.

- Merino MJ, Torres-Cabala C, Pinto P, et al.: The morphologic spectrum of kidney tumors in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC) syndrome. Am J Surg Pathol 31 (10): 1578-85, 2007.

- Launonen V, Vierimaa O, Kiuru M, et al.: Inherited susceptibility to uterine leiomyomas and renal cell cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 (6): 3387-92, 2001.

- Refae MA, Wong N, Patenaude F, et al.: Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: an unusual and aggressive form of hereditary renal carcinoma. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 4 (4): 256-61, 2007.

- American Society of Clinical Oncology: American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol 21 (12): 2397-406, 2003.

- Robson ME, Storm CD, Weitzel J, et al.: American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol 28 (5): 893-901, 2010.

- Wei MH, Toure O, Glenn GM, et al.: Novel mutations in FH and expansion of the spectrum of phenotypes expressed in families with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. J Med Genet 43 (1): 18-27, 2006.

- Shuch B, Singer EA, Bratslavsky G: The surgical approach to multifocal renal cancers: hereditary syndromes, ipsilateral multifocality, and bilateral tumors. Urol Clin North Am 39 (2): 133-48, v, 2012.

- Patel VM, Handler MZ, Schwartz RA, et al.: Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer syndrome: An update and review. J Am Acad Dermatol 77 (1): 149-158, 2017.

- Zavoshi S, Lu E, Boutros PC, et al.: Fumarate Hydratase Variants and Their Association With Paraganglioma/Pheochromocytoma. Urology 176: 106-114, 2023.

- Grubb RL, Franks ME, Toro J, et al.: Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: a syndrome associated with an aggressive form of inherited renal cancer. J Urol 177 (6): 2074-9; discussion 2079-80, 2007.

- Pfaffenroth EC, Linehan WM: Genetic basis for kidney cancer: opportunity for disease-specific approaches to therapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther 8 (6): 779-90, 2008.

- Ritzmann S, Hanneken S, Neumann NJ, et al.: Type 2 segmental manifestation of cutaneous leiomyomatosis in four unrelated women with additional uterine leiomyomas (Reed's Syndrome). Dermatology 212 (1): 84-7, 2006.

- Naik HB, Steinberg SM, Middelton LA, et al.: Efficacy of Intralesional Botulinum Toxin A for Treatment of Painful Cutaneous Leiomyomas: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Dermatol 151 (10): 1096-102, 2015.

- Isaacs JS, Jung YJ, Mole DR, et al.: HIF overexpression correlates with biallelic loss of fumarate hydratase in renal cancer: novel role of fumarate in regulation of HIF stability. Cancer Cell 8 (2): 143-53, 2005.

- Pollard PJ, Brière JJ, Alam NA, et al.: Accumulation of Krebs cycle intermediates and over-expression of HIF1alpha in tumours which result from germline FH and SDH mutations. Hum Mol Genet 14 (15): 2231-9, 2005.

- Xie H, Valera VA, Merino MJ, et al.: LDH-A inhibition, a therapeutic strategy for treatment of hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. Mol Cancer Ther 8 (3): 626-35, 2009.

- Yamasaki T, Tran TA, Oz OK, et al.: Exploring a glycolytic inhibitor for the treatment of an FH-deficient type-2 papillary RCC. Nat Rev Urol 8 (3): 165-71, 2011.

- Linehan WM, Srinivasan R, Garcia JA: Non-clear cell renal cancer: disease-based management and opportunities for targeted therapeutic approaches. Semin Oncol 40 (4): 511-20, 2013.

- Linehan WM, Pinto PA, Srinivasan R, et al.: Identification of the genes for kidney cancer: opportunity for disease-specific targeted therapeutics. Clin Cancer Res 13 (2 Pt 2): 671s-679s, 2007.

- Sourbier C, Ricketts CJ, Matsumoto S, et al.: Targeting ABL1-mediated oxidative stress adaptation in fumarate hydratase-deficient cancer. Cancer Cell 26 (6): 840-50, 2014.

Prognosis

Prognosis is quite good for cutaneous and uterine manifestations of hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC). Local management of cutaneous manifestations, when required, and hysterectomy, where indicated, address these sites fairly effectively and with minimal long-term consequences. The incidence of uterine leiomyosarcomas is likely quite low and is unlikely to substantively affect median survival at a cohort level. Renal cell cancer (RCC) in the context of HLRCC is a considerably more ominous manifestation, and the HLRCC patients who develop RCC [

References:

- Shuch B, Vourganti S, Ricketts CJ, et al.: Defining early-onset kidney cancer: implications for germline and somatic mutation testing and clinical management. J Clin Oncol 32 (5): 431-7, 2014.

- Launonen V, Vierimaa O, Kiuru M, et al.: Inherited susceptibility to uterine leiomyomas and renal cell cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 (6): 3387-92, 2001.

- Toro JR, Nickerson ML, Wei MH, et al.: Mutations in the fumarate hydratase gene cause hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer in families in North America. Am J Hum Genet 73 (1): 95-106, 2003.

- Alam NA, Barclay E, Rowan AJ, et al.: Clinical features of multiple cutaneous and uterine leiomyomatosis: an underdiagnosed tumor syndrome. Arch Dermatol 141 (2): 199-206, 2005.

- Forde C, Lim DHK, Alwan Y, et al.: Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer: Clinical, Molecular, and Screening Features in a Cohort of 185 Affected Individuals. Eur Urol Oncol 3 (6): 764-772, 2020.

- Grubb RL, Franks ME, Toro J, et al.: Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer: a syndrome associated with an aggressive form of inherited renal cancer. J Urol 177 (6): 2074-9; discussion 2079-80, 2007.

- Chen F, Zhang Y, Şenbabaoğlu Y, et al.: Multilevel Genomics-Based Taxonomy of Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cell Rep 14 (10): 2476-89, 2016.

Future Directions

There are two major unmet needs, other than the availability of effective medical therapy for metastatic disease, in the management of patients with hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC). The first is the ability to predict who will develop renal cell cancer to allow detection earlier and with a higher degree of precision. The development of diagnostic blood-based tests or imaging tools that permit cost-effective surveillance of the kidneys of patients with HLRCC would have a major positive effect on the outcomes of these individuals. The second major unmet need is for a more accurate determination of the genotype -phenotype correlations for various genetic lesions found in the FHgene. New polymorphisms in the FH gene are frequently of uncertain significance, and considerable effort needs to be expended to determine their clinical significance. Devising in silico prediction tools and linking these to robust patient databases and registries will expand our understanding of specific FH gene variants.

Latest Updates to This Summary (11 / 06 / 2024)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Added

Added

Revised

This summary is written and maintained by the

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the genetics of hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer are:

- Alexandra Perez Lebensohn, MS, CGC (National Cancer Institute)

- Brian Matthew Shuch, MD (UCLA Health)

- Ramaprasad Srinivasan, MD, PhD (National Cancer Institute)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Cancer Genetics Editorial Board uses a

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Cancer Genetics Editorial Board. PDQ Hereditary Leiomyomatosis and Renal Cell Cancer. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at:

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our

Last Revised: 2024-11-06

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the

Healthwise, Healthwise for every health decision, and the Healthwise logo are trademarks of Ignite Healthwise, LLC.

Page Footer

I want to...

Audiences

Secure Member Sites

The Cigna Group Information

Disclaimer

Individual and family medical and dental insurance plans are insured by Cigna Health and Life Insurance Company (CHLIC), Cigna HealthCare of Arizona, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Illinois, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Georgia, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of North Carolina, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of South Carolina, Inc., and Cigna HealthCare of Texas, Inc. Group health insurance and health benefit plans are insured or administered by CHLIC, Connecticut General Life Insurance Company (CGLIC), or their affiliates (see

All insurance policies and group benefit plans contain exclusions and limitations. For availability, costs and complete details of coverage, contact a licensed agent or Cigna sales representative. This website is not intended for residents of New Mexico.