Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage

Plans through your employer

Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

Learn

Living or working abroad?

Lymphedema (PDQ®): Supportive care - Health Professional Information [NCI]

Overview

Lymphedema occurs when disruption of normal lymphatic drainage leads to accumulation of protein-rich lymph fluid in the interstitial space. Cancer survivors who experience lymphedema report poor physical functioning, impaired ability to engage in normal activities of daily living, and increased psychological distress.[

Estimates of the prevalence of lymphedema vary widely due to differences in the type of cancer, measurement methods, diagnostic criteria, and timing of evaluations relative to cancer diagnosis and treatment. In a survey conducted in 2006 and 2010, 6,593 cancer survivors were asked to identify ongoing concerns. Approximately 20% of respondents reported concerns related to lymphedema. Of these individuals, 50% to 60% reported receiving care for lymphedema.[

Lymphedema is a common delayed effect of cancer treatment that negatively impacts survivors' quality of life. This summary reviews the anatomy of the lymphatic system, the pathophysiology of lymphedema secondary to cancer, and epidemiology. The summary also provides clinicians with information related to risk factors, diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. The summary does not deal with congenital lymphedema or lymphedema not related to cancer.

In this summary, unless otherwise stated, evidence and practice issues as they relate to adults are discussed. The evidence and application to practice related to children may differ significantly from information related to adults. When specific information about the care of children is available, it is summarized under its own heading.

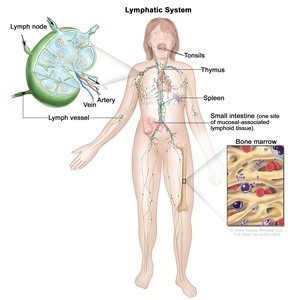

Anatomy of the Lymphatic System

The human lymphatic system generally includes superficial or primary lymphatic vessels that form a complex dermal network of capillary-like channels. Primary lymphatic vessels lack muscular walls and do not have valves. They drain into larger, secondary lymphatic vessels located in the subdermal space. Secondary lymphatic vessels run parallel to the superficial veins and drain into deeper lymphatic vessels located in the subcutaneous fat adjacent to the fascia. Unlike the primary vessels, the secondary and deeper lymphatic vessels have muscular walls and numerous valves to accomplish active and unidirectional lymphatic flow.

An intramuscular system of lymphatic vessels that parallels the deep arteries and drains the muscular compartment, joints, and synovium also exists. The superficial and deep lymphatic systems probably function independently, except in abnormal states, although there is evidence that they communicate near lymph nodes.[

The lymph system is part of the body's immune system and is made up of tissues and organs that help protect the body from infection and disease. These include the tonsils, adenoids (not shown), thymus, spleen, bone marrow, lymph vessels, and lymph nodes. Lymph tissue is also found in many other parts of the body, including the small intestine.

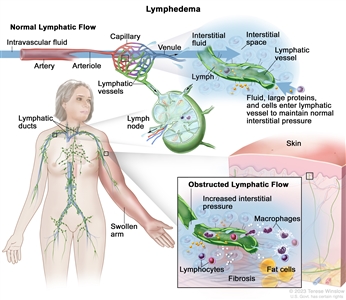

Pathophysiology of Lymphedema

Body fluids can be discussed in terms of their composition and the specific fluid compartment where they are located. Intracellular fluid includes all fluid enclosed by the plasma membranes of cells. Extracellular fluid (ECF) surrounds all cells in the body. ECF has two primary constituents: intravascular plasma and the interstitial fluid that surrounds all cells not in the plasma. Lymphedema is the abnormal accumulation of protein-rich fluid in the interstitial space that is accompanied by inflammation and, eventually, fibrosis.

The formation of interstitial fluid comes from the movement of intravascular fluid across the capillary membranes due to arteriolar blood pressure. Much of the interstitial fluid returns to the intravascular fluid via the postcapillary venules. The dynamics of fluid production are influenced by arterial and venous hydrostatic pressures, tissue pressure, oncotic pressures of the intravascular and interstitial fluid, and membrane permeability. Normally, the dynamics favor a net gain of interstitial fluid, with the excess removed via lymphatic channels. Because lymphatic vessels often lack a basement membrane, they can resorb molecules too large for venous uptake as well. In short, the lymphatic system controls the pressure, volume, and composition of the interstitial fluid.

Lymphatic obstruction leads to increased interstitial fluid, which often contains large proteins and cellular debris. Through mechanisms not fully understood, the increased interstitial fluid induces inflammation, destruction or sclerosis of the lymphatic vessels, fibrosis, and, ultimately, adipose tissue hypertrophy.

The lymphatic vessels normally maintain normal interstitial pressures by removing the excess interstitial fluid that results from the imbalance between the intravascular fluid that enters from the arterioles and exits into the venules. Large proteins and cells that cannot exit the interstitial space through the venules leave the interstitial fluid through the lymphatic vessels. As the lymph moves through the lymphatic vessels, it passes through lymph nodes and eventually into one of two lymphatic ducts that empty into a large vein near the heart. In lymphedema, the flow of lymph through the lymphatic vessels is disrupted or blocked. This leads to increased interstitial pressure and an accumulation of interstitial fluid, large proteins, and cellular debris in the interstitial space, which induces inflammation. The inflammation may cause further damage to the lymphatic vessels. The macrophages and lymphocytes release inflammatory markers, which causes fibrosis, fat cell hypertrophy, and the classical sign of swelling. Lymphedema may be caused by cancer or cancer treatment.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Accurate estimates of the incidence and prevalence of lymphedema are difficult to provide, due in part to differences in the definition of lymphedema (e.g., patient self-reports vs. objective volume measurements) and the timing of assessment for lymphedema relative to cancer treatment. Other factors are differences in surgical techniques related to the type of lymph node dissection or the total dose, fractions, and field of radiation administered.

Common risk factors for developing lymphedema include the following:

- Extent of local surgery.

- Anatomical location of lymph node dissection.

- Radiation to lymph nodes.

- Localized infection or delayed wound healing.

- Tumor causing lymphatic obstruction of the anterior cervical, thoracic, axillary, pelvic, or abdominal nodes.

- Intrapelvic or intra-abdominal tumors that involve or directly compress lymphatic vessels and/or the cisterna chyli and thoracic duct.

- Having a higher disease stage.

- Overweight (body mass index [BMI] ≥25 kg/m2) or obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2).[

9 ] - Black race and Hispanic ethnicity.[

10 ] - Rurality.[

10 ]

References:

- Ridner SH: Quality of life and a symptom cluster associated with breast cancer treatment-related lymphedema. Support Care Cancer 13 (11): 904-11, 2005.

- Dunberger G, Lindquist H, Waldenström AC, et al.: Lower limb lymphedema in gynecological cancer survivors--effect on daily life functioning. Support Care Cancer 21 (11): 3063-70, 2013.

- Zhang X, McLaughlin EM, Krok-Schoen JL, et al.: Association of Lower Extremity Lymphedema With Physical Functioning and Activities of Daily Living Among Older Survivors of Colorectal, Endometrial, and Ovarian Cancer. JAMA Netw Open 5 (3): e221671, 2022.

- Pyszel A, Malyszczak K, Pyszel K, et al.: Disability, psychological distress and quality of life in breast cancer survivors with arm lymphedema. Lymphology 39 (4): 185-92, 2006.

- Gjorup CA, Groenvold M, Hendel HW, et al.: Health-related quality of life in melanoma patients: Impact of melanoma-related limb lymphoedema. Eur J Cancer 85: 122-132, 2017.

- Beckjord EB, Reynolds KA, van Londen GJ, et al.: Population-level trends in posttreatment cancer survivors' concerns and associated receipt of care: results from the 2006 and 2010 LIVESTRONG surveys. J Psychosoc Oncol 32 (2): 125-51, 2014.

- Paskett ED, Le-Rademacher J, Oliveri JM, et al.: A randomized study to prevent lymphedema in women treated for breast cancer: CALGB 70305 (Alliance). Cancer 127 (2): 291-299, 2021.

- Horsley JS, Styblo T: Lymphedema in the postmastectomy patient. In: Bland KI, Copeland EM, eds.: The Breast: Comprehensive Management of Benign and Malignant Diseases. Saunders, 1991, pp 701-6.

- McLaughlin SA, Brunelle CL, Taghian A: Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: Risk Factors, Screening, Management, and the Impact of Locoregional Treatment. J Clin Oncol 38 (20): 2341-2350, 2020.

- Montagna G, Zhang J, Sevilimedu V, et al.: Risk Factors and Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Patients With Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema. JAMA Oncol 8 (8): 1195-1200, 2022.

Disease-Specific Lymphedema

Breast Cancer

A systematic review found the prevalence of lymphedema to be 21.4% (14.9%–29.8%) in patients with breast cancer.[

Several risk factors for breast cancer–related lymphedema (BCRL) were demonstrated in a study using data from a 2-year, prospective observational study of 304 patients with breast cancer who had axillary lymph node dissection and radiation therapy. The cumulative incidence of lymphedema was measured by a more than 10% increase in arm volume, and univariate and multivariable analyses were performed. On multivariable analysis, Black race and Hispanic ethnicity (odds ratio [OR], 3.88; 95% CI, 2.14–7.08, and OR, 3.01; 95% CI, 1.10–7.62, respectively; P < .001 for each), receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy (OR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.16–3.95; P = .01), older age (OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02–1.07 per 1-year increase; P = .001), and a longer follow-up interval (OR, 1.57; 95% CI, 1.30–1.90 per 6-month increase; P < .001) were independently associated with an increased risk.[

Another study examined risk factors for BCRL related to treatment, comorbidities, and lifestyle in 918 women enrolled in a Prospective Surveillance and Early Intervention (PSEI) trial. Women were randomly assigned to either bioimpedance spectroscopy (BIS) or tape measurement (TM).[

Gynecological Cancers

A cohort study supports the evidence that a significant proportion of women experience lower-limb lymphedema after treatment of gynecological cancer or colorectal cancer. The highest prevalence (36.5%) among ovarian cancer survivors, followed by endometrial cancer survivors (32.5%) and colorectal cancer survivors (31.4%).[

In one study, 802 of 1,774 women diagnosed with a gynecological cancer between 1999 and 2004 responded to a survey about lymphedema.[

Serial limb volume measurements were obtained from a cohort of women who underwent a lymph node dissection for vulvar (n = 42), endometrial (n = 734), or cervical (n = 138) cancer 4 to 6 weeks after surgery and then every 3 months.[

Head and Neck Cancer

Patients with head and neck cancer are susceptible to external and internal lymphedema. External lymphedema typically presents with submental edema or lower neck swelling. Internal lymphedema is more widely distributed in the anatomical regions of the oropharynx. In a small cross-sectional study with video-assisted examinations, 59 of 61 patients had some degree of lymphedema.[

Melanoma

One single-center, cross-sectional study reported on lymphedema after either sentinel lymph node biopsy or lymph node dissection in 435 patients who were treated for melanoma between 1997 and 2015.[

Prostate Cancer

There are few studies of lymphedema after prostate cancer therapy. A small cross-sectional survey of men who underwent radical prostatectomy reported that 19 of 54 respondents (35.2%) had bilateral lower-extremity lymphedema.[

Sarcoma

One study measured patient demographics, surgical outcomes data, functional outcomes, and lymphedema severity with a validated scale for 289 patients who underwent limb preservation surgery of an extremity sarcoma between 2000 and 2007.[

References:

- DiSipio T, Rye S, Newman B, et al.: Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol 14 (6): 500-15, 2013.

- Giuliano AE, Ballman KV, McCall L, et al.: Effect of Axillary Dissection vs No Axillary Dissection on 10-Year Overall Survival Among Women With Invasive Breast Cancer and Sentinel Node Metastasis: The ACOSOG Z0011 (Alliance) Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 318 (10): 918-926, 2017.

- McLaughlin SA, Brunelle CL, Taghian A: Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: Risk Factors, Screening, Management, and the Impact of Locoregional Treatment. J Clin Oncol 38 (20): 2341-2350, 2020.

- Armer JM, Ballman KV, McCall L, et al.: Factors Associated With Lymphedema in Women With Node-Positive Breast Cancer Treated With Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy and Axillary Dissection. JAMA Surg 154 (9): 800-809, 2019.

- Montagna G, Zhang J, Sevilimedu V, et al.: Risk Factors and Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Patients With Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema. JAMA Oncol 8 (8): 1195-1200, 2022.

- Koelmeyer LA, Gaitatzis K, Dietrich MS, et al.: Risk factors for breast cancer-related lymphedema in patients undergoing 3 years of prospective surveillance with intervention. Cancer 128 (18): 3408-3415, 2022.

- Zhang X, McLaughlin EM, Krok-Schoen JL, et al.: Association of Lower Extremity Lymphedema With Physical Functioning and Activities of Daily Living Among Older Survivors of Colorectal, Endometrial, and Ovarian Cancer. JAMA Netw Open 5 (3): e221671, 2022.

- Beesley V, Janda M, Eakin E, et al.: Lymphedema after gynecological cancer treatment : prevalence, correlates, and supportive care needs. Cancer 109 (12): 2607-14, 2007.

- Ryan M, Stainton MC, Slaytor EK, et al.: Aetiology and prevalence of lower limb lymphoedema following treatment for gynaecological cancer. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 43 (2): 148-51, 2003.

- Carter J, Huang HQ, Armer J, et al.: GOG 244 - The LymphEdema and Gynecologic cancer (LEG) study: The association between the gynecologic cancer lymphedema questionnaire (GCLQ) and lymphedema of the lower extremity (LLE). Gynecol Oncol 155 (3): 452-460, 2019.

- Jeans C, Brown B, Ward EC, et al.: Comparing the prevalence, location, and severity of head and neck lymphedema after postoperative radiotherapy for oral cavity cancers and definitive chemoradiotherapy for oropharyngeal, laryngeal, and hypopharyngeal cancers. Head Neck 42 (11): 3364-3374, 2020.

- Gjorup CA, Groenvold M, Hendel HW, et al.: Health-related quality of life in melanoma patients: Impact of melanoma-related limb lymphoedema. Eur J Cancer 85: 122-132, 2017.

- Deban M, Vallance P, Jost E, et al.: Higher Rate of Lymphedema with Inguinal versus Axillary Complete Lymph Node Dissection for Melanoma: A Potential Target for Immediate Lymphatic Reconstruction? Curr Oncol 29 (8): 5655-5663, 2022.

- Moody JA, Botham SJ, Dahill KE, et al.: Complications following completion lymphadenectomy versus therapeutic lymphadenectomy for melanoma - A systematic review of the literature. Eur J Surg Oncol 43 (9): 1760-1767, 2017.

- Neuberger M, Schmidt L, Wessels F, et al.: Onset and burden of lower limb lymphedema after radical prostatectomy: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer 30 (2): 1303-1313, 2022.

- Friedmann D, Wunder JS, Ferguson P, et al.: Incidence and Severity of Lymphoedema following Limb Salvage of Extremity Soft Tissue Sarcoma. Sarcoma 2011: 289673, 2011.

Diagnosis of Lymphedema

Signs, Symptoms, and Physical Examination

Lymphedema is typically evident by clinical findings such as unilateral, nonpitting edema, usually with involvement of the digits, in a patient with known risk factors (e.g., a breast cancer patient with previous axillary dissection). Other causes of limb swelling, including deep venous thrombosis, malignancy, and infection, should be considered in the differential diagnosis and excluded with appropriate studies, if indicated.

Lymphedema in patients with head and neck cancer can present slightly differently. External lymphedema does show swelling in the head and neck area, but internal lymphedema does not. Instead, patients with lymphedema related to internal head and neck cancer can present with complaints of voice changes, dysphagia, and possible difficulty breathing.

Diagnostic Testing

Limb measurements

The wide variety of methods for evaluating limb volume and lack of standardization make it difficult for the clinician to assess the at-risk limb. Options include water displacement, tape measurement, infrared scanning, and bioelectrical impedance measures.[

The most common method for diagnosing upper-extremity lymphedema is circumferential upper-extremity measurement using specific anatomical landmarks.[

The water displacement method is another way to evaluate arm edema. A volume difference of 200 mL or more between the affected and opposite arms is typically considered to be a cutoff point to define lymphedema.[

Magnetic resonance lymphography (MRL)

This technique involves the intracutaneous injection of a paramagnetic contrast agent, followed by imaging of the lymphatic anatomy, dermal flow patterns, and adjacent fatty tissue. One study of 50 women with breast cancer–related lymphedema compared the lymphatic vessel morphology in their affected and unaffected arms.[

Staging and grading of severity

The staging system of the ISL reflects likely changes over time based on the pathophysiology of lymphedema. The stages include the following:

- Stage 0: This stage, referred to as subclinical lymphedema, is characterized by impaired lymph flow.

- Stage I: This stage is spontaneously reversible and typically marked by pitting edema, an increase in upper-extremity girth, and heaviness.

- Stage II: This moderate stage is characterized by a spongy consistency of the tissue without signs of pitting edema. Tissue fibrosis can then cause the limbs to harden and increase in size.[

2 ] The swelling at this stage is mostly fluid. - Stage III: In the most advanced stage,[

2 ] swelling is mostly secondary to fat hypertrophy, so there is no pitting edema.

The severity of lymphedema may be evaluated using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), which was developed for grading adverse events in the context of clinical trials.[

- Grade 1: 5% to 10% interlimb discrepancy in volume or circumference at point of greatest visible difference; swelling or obscuration of anatomical architecture on close inspection; pitting edema.

- Grade 2: More than 10% to 30% interlimb discrepancy in volume or circumference at point of greatest visible difference; readily apparent obscuration of anatomical architecture; obliteration of skin folds; readily apparent deviation from normal anatomical contour.

- Grade 3: More than 30% interlimb discrepancy in volume; lymphorrhea; gross deviation from normal anatomical contour; interference with activities of daily living (ADL).

- Grade 4: Progression to malignancy (e.g., lymphangiosarcoma); amputation indicated; disabling lymphedema.

The fifth version of the CTCAE is more streamlined and does not include limb volumes:[

- Grade 1: Trace thickening or faint discoloration.

- Grade 2: Marked discoloration; leathery skin texture; papillary formation; limitation in instrumental ADL.

- Grade 3: Severe symptoms; limitation in self-care ADL.

References:

- Ridner SH, Montgomery LD, Hepworth JT, et al.: Comparison of upper limb volume measurement techniques and arm symptoms between healthy volunteers and individuals with known lymphedema. Lymphology 40 (1): 35-46, 2007.

- Bicego D, Brown K, Ruddick M, et al.: Exercise for women with or at risk for breast cancer-related lymphedema. Phys Ther 86 (10): 1398-405, 2006.

- Petrek JA: Commentary: prospective trial of complete decongestive therapy for upper extremity lymphedema after breast cancer therapy. Cancer J 10 (1): 17-9, 2004.

- Mondry TE, Riffenburgh RH, Johnstone PA: Prospective trial of complete decongestive therapy for upper extremity lymphedema after breast cancer therapy. Cancer J 10 (1): 42-8; discussion 17-9, 2004 Jan-Feb.

- Sheng L, Zhang G, Li S, et al.: Magnetic Resonance Lymphography of Lymphatic Vessels in Upper Extremity With Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema. Ann Plast Surg 84 (1): 100-105, 2020.

- Executive Committee: The Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Lymphedema: 2016 Consensus Document of the International Society of Lymphology. Lymphology 49 (4): 170-84, 2016.

- Cheville AL, McGarvey CL, Petrek JA, et al.: The grading of lymphedema in oncology clinical trials. Semin Radiat Oncol 13 (3): 214-25, 2003.

- National Cancer Institute: Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), Version 5.0. Bethesda, Md: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, 2017.

Available online . Last accessed Dec. 18, 2024.

Prevention and Treatment Options Overview for Lymphedema

There are many potential interventions to reduce the risk of lymphedema or ameliorate its negative consequences. In general, the prevention and treatment interventions may be divided into nonsurgical and surgical approaches. Nonsurgical interventions may be further divided into pharmacological, compressive, or exercise related. Conservative options should be tried and exhausted prior to considering surgical options. This section provides an overview of the various interventions, followed by a more detailed analysis of individual trials based on the type of cancer.

Nonsurgical Options

Compression garments

Compression garments are used to prevent and treat lymphedema by helping to decrease excess formation of interstitial fluid, prevent reflux of lymphatic fluid, and give a barrier to help muscle pumping of fluid up the lymphatic system.[

Elastic garments are best used for stage I lymphedema and lymphedema that has been converted to stage II after complete decongestive therapy (CDT).

Intermittent external pneumatic compression

This approach should be used in conjunction with compression garments and only if compression is not enough to prevent or treat lymphedema. Concerns regarding the use of intermittent pneumatic compression include the optimum amount of pressure, treatment schedule, and the need for maintenance therapy after the initial reduction in edema.[

Intermittent external pneumatic compression may improve lymphedema management when used adjunctively with decongestive lymphatic therapy. A small randomized trial of 23 women with new breast cancer–associated lymphedema found an additional significant volume reduction, compared with manual lymphatic drainage alone (45% vs. 26%).[

There are several barriers to multidisciplinary decongestive therapy, including cost, inadequate number of trained therapists, and time commitment. In response to these barriers, a group of researchers conducted a trial of a garment under commercial development.[

Complete decongestive therapy (CDT)

CDT is the standard of care for stage II lymphedema. However, the optimal program has not been established.

CDT has two phases:

- Phase 1—Decongestion/reduction: Skin/wound care, exercise, manual lymphatic drainage, and compression bandages, performed daily for an average of 15 days.

- Phase 2—Maintenance: Skin/wound care, exercise, manual lymphatic drainage as needed, and compression garments.

One study compared manual lymphatic drainage with exercise to treat lymphedema in 39 people with oral cavity cancer.[

A systematic review of manual lymphatic drainage in patients with breast cancer reported on ten studies.[

Physical exercise

Physical exercise may be valuable in the treatment of lymphedema for several reasons, including improvement in lymph flow from muscle contractions and overall cardiovascular function.[

A systematic review and meta-analysis reported on 12 prevention and 36 treatment studies of exercise to either prevent or treat cancer-related lymphedema.[

The American College of Sports Medicine advises that a supervised, progressive resistance exercise program is safe for patients with or at risk for lymphedema after breast cancer. There is not adequate data about the safety of unsupervised exercise. The safety of exercise in other cancers is unknown.[

Pharmacological therapy

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

The potential benefit of the NSAID ketoprofen on lymphedema was demonstrated in a pair of small trials.[

Surgical Options

The surgical options for the treatment of lymphedema include lymphatico-venous anastomoses (LVA), vascularized lymph node transplantation (VLNT), and reduction of excess tissue volume by excision of liposuction. Several informative reviews describe the surgical decision making involved in selecting patients and the type of operation.[

There are limited data to guide the choice between liposuction and microsurgical techniques, and some investigators propose a combined approach.[

Lymphatico-venous anastomosis

LVA surgery is typically used in patients with early-grade lymphedema due to difficulties in finding lymphatic vessels. One study reported results for 42 patients with later-grade, lower-extremity lymphedema who underwent preoperative magnetic resonance lymphangiography and ultrasound.[

Immediate lymphatic reconstruction at the time of cancer surgery is under active investigation.

Vascularized lymph node transfer

VLNT involves harvesting healthy lymph nodes and their relevant venous and arterial vessels from a donor site and transferring them to the nodal basin of the affected extremity. The proposed mechanisms of action include providing alternative routes of lymphatic drainage and encouraging lymphangiogenesis to provide new lymph vessels to the extremity. At present, there is scant but promising clinical data on the efficacy of VLNT.[

A systematic review and summary of patients with breast cancer–related lymphedema who underwent CDT or VLNT [

In a retrospective study of 124 patients with breast cancer–related lymphedema, the degree of improvement in limb circumference and reduction in episodes of cellulitis appeared to be greater in patients who underwent VLNT than in those who underwent LVA.[

Liposuction

Nonpitting chronic lymphedema may be due to adipose tissue hypertrophy. In this case, liposuction to remove the excess adipose tissue is an option. Compression garments are still needed after the liposuction. In addition, excision of the redundant skin after liposuction may be required.[

One retrospective study compared the frequency of documented episodes of erysipelas in 130 patients before and after they underwent liposuction.[

Laser therapy

Low-level laser therapy (LLT) is a noninvasive technique in which affected tissues receive phototherapy of various wavelengths within 650 to 1,000 nanometers. The role of LLT in the care of people with lymphedema is not established, although a 2017 systematic review found promising evidence.[

References:

- Nadal Castells MJ, Ramirez Mirabal E, Cuartero Archs J, et al.: Effectiveness of Lymphedema Prevention Programs With Compression Garment After Lymphatic Node Dissection in Breast Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Front Rehabil Sci 2: 727256, 2021.

- Dini D, Del Mastro L, Gozza A, et al.: The role of pneumatic compression in the treatment of postmastectomy lymphedema. A randomized phase III study. Ann Oncol 9 (2): 187-90, 1998.

- Szuba A, Achalu R, Rockson SG: Decongestive lymphatic therapy for patients with breast carcinoma-associated lymphedema. A randomized, prospective study of a role for adjunctive intermittent pneumatic compression. Cancer 95 (11): 2260-7, 2002.

- Ridner SH, Dietrich MS, Deng J, et al.: Advanced pneumatic compression for treatment of lymphedema of the head and neck: a randomized wait-list controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 29 (2): 795-803, 2021.

- Lerman M, Gaebler JA, Hoy S, et al.: Health and economic benefits of advanced pneumatic compression devices in patients with phlebolymphedema. J Vasc Surg 69 (2): 571-580, 2019.

- Tsai KY, Liao SF, Chen KL, et al.: Effect of early interventions with manual lymphatic drainage and rehabilitation exercise on morbidity and lymphedema in patients with oral cavity cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 101 (42): e30910, 2022.

- Lin Y, Yang Y, Zhang X, et al.: Manual Lymphatic Drainage for Breast Cancer-related Lymphedema: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin Breast Cancer 22 (5): e664-e673, 2022.

- Hayes SC, Singh B, Reul-Hirche H, et al.: The Effect of Exercise for the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer-Related Lymphedema: A Systematic Review with Meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc 54 (8): 1389-1399, 2022.

- Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, et al.: Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer-related lymphedema. N Engl J Med 361 (7): 664-73, 2009.

- Singh B, Disipio T, Peake J, et al.: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Exercise for Those With Cancer-Related Lymphedema. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 97 (2): 302-315.e13, 2016.

- Do JH, Kim W, Cho YK, et al.: EFFECTS OF RESISTANCE EXERCISES AND COMPLEX DECONGESTIVE THERAPY ON ARM FUNCTION AND MUSCULAR STRENGTH IN BREAST CANCER RELATED LYMPHEDEMA. Lymphology 48 (4): 184-96, 2015.

- Campbell KL, Winters-Stone KM, Wiskemann J, et al.: Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors: Consensus Statement from International Multidisciplinary Roundtable. Med Sci Sports Exerc 51 (11): 2375-2390, 2019.

- Rockson SG, Tian W, Jiang X, et al.: Pilot studies demonstrate the potential benefits of antiinflammatory therapy in human lymphedema. JCI Insight 3 (20): , 2018.

- Schaverien MV, Coroneos CJ: Surgical Treatment of Lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 144 (3): 738-758, 2019.

- Forte AJ, Boczar D, Huayllani MT, et al.: Pharmacotherapy Agents in Lymphedema Treatment: A Systematic Review. Cureus 11 (12): e6300, 2019.

- Engel H, Lin CY, Huang JJ, et al.: Outcomes of Lymphedema Microsurgery for Breast Cancer-related Lymphedema With or Without Microvascular Breast Reconstruction. Ann Surg 268 (6): 1076-1083, 2018.

- Cha HG, Oh TM, Cho MJ, et al.: Changing the Paradigm: Lymphovenous Anastomosis in Advanced Stage Lower Extremity Lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 147 (1): 199-207, 2021.

- Gould DJ, Mehrara BJ, Neligan P, et al.: Lymph node transplantation for the treatment of lymphedema. J Surg Oncol 118 (5): 736-742, 2018.

- Fish ML, Grover R, Schwarz GS: Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Surgical vs Nonsurgical Treatment of Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: A Systematic Review. JAMA Surg 155 (6): 513-519, 2020.

- Aljaaly HA, Fries CA, Cheng MH: Dorsal Wrist Placement for Vascularized Submental Lymph Node Transfer Significantly Improves Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 7 (2): e2149, 2019.

- Gratzon A, Schultz J, Secrest K, et al.: Clinical and Psychosocial Outcomes of Vascularized Lymph Node Transfer for the Treatment of Upper Extremity Lymphedema After Breast Cancer Therapy. Ann Surg Oncol 24 (6): 1475-1481, 2017.

- Chen WF, Zeng WF, Hawkes PJ, et al.: Lymphedema Liposuction with Immediate Limb Contouring. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 7 (11): e2513, 2019.

- Lee D, Piller N, Hoffner M, et al.: Liposuction of Postmastectomy Arm Lymphedema Decreases the Incidence of Erysipelas. Lymphology 49 (2): 85-92, 2016.

- Hoffner M, Ohlin K, Svensson B, et al.: Liposuction Gives Complete Reduction of Arm Lymphedema following Breast Cancer Treatment-A 5-year Prospective Study in 105 Patients without Recurrence. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 6 (8): e1912, 2018.

- Baxter GD, Liu L, Petrich S, et al.: Low level laser therapy (Photobiomodulation therapy) for breast cancer-related lymphedema: a systematic review. BMC Cancer 17 (1): 833, 2017.

- Menzer C, Aleisa A, Wilson BN, et al.: Efficacy of laser CO2 treatment for refractory lymphedema secondary to cancer treatments. Lasers Surg Med 54 (3): 337-341, 2022.

Disease-Specific Interventions for Prevention or Treatment of Lymphedema

Breast Cancer: Prevention of Lymphedema

Compression garments

A randomized study of women who underwent an axillary dissection suggested that compression sleeves worn from the first postoperative day until 3 months after completion of adjuvant therapy reduced the risk of lymphedema.[

Exercise

A randomized trial suggested that exercise might help prevent lymphedema after breast cancer surgery.[

A 2021 randomized trial studied patients with breast cancer who underwent either an axillary or sentinel lymph node dissection.[

At present, exercise therapy with compression garments may not effectively prevent lymphedema. Exercise with other interventions has been investigated. For example, one study reported the results of a randomized trial of manual lymphatic drainage in addition to exercise therapy in preventing lymphedema.[

Breast Cancer: Treatment of Lymphedema

Complete decongestive therapy (CDT)

Compression sleeves alone may prevent progression of less severe lymphedema, but women often need more intensive interventions.[

Physical exercise

The results of randomized trials of physical exercise compared with usual care do not consistently demonstrate a benefit for patients with breast cancer and lymphedema. One study showed that women who underwent wide excision and axillary dissection and were randomly assigned to a supervised exercise program (3 hours per week for 12 weeks) reported fewer lymphedema-related symptoms than women assigned to a control group.[

Based on promising results of a facility-based exercise intervention, one trial used a 2 x 2 factorial design to test a home-based exercise program, with or without a weight-loss intervention led by a dietitian.[

Lymph node transplantation

A randomized trial of microsurgical lymph node transplantation and compression-physiotherapy versus compression-physiotherapy alone was reported.[

Cervical Cancer: Prevention of Lymphedema

One study enrolled 120 women with cervical cancer who underwent a laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy. Participants were randomly assigned to an education-alone intervention or a CDT intervention.[

Head and Neck Cancer: Treatment of Lymphedema

Systematic review

A systematic review examined publications related to lymphedema treatment in patients who had been treated for head and neck cancers.[

CDT

A small randomized trial in patients with lymphedema after surgery for head and neck cancer assigned 21 patients to one of three groups: control (n = 7), CDT (n = 7), and home-based therapy (n = 7).[

Advanced pneumatic compression device

The shortage of trained lymphedema therapists and the inconvenience of multiple clinic visits have encouraged the development of a device patients can use at home. In a small randomized trial of such a device, patients were assigned to the device (n = 24) or a wait-list control (n = 25).[

Liposuction

There is a small randomized trial of submental liposuction in patients who complained of swelling after treatment of head and neck cancer. The ten patients who underwent liposuction reported greater improvements in personal appearance, compared with control subjects, at 6 months. No adverse effects from liposuction were reported.[

Sarcoma of the Extremity: Prevention of Lymphedema

One study compared the incidence of lymphedema in a cohort of eight patients with thigh sarcoma, who had lymphatico-venous anastomoses performed in combination with resection of thigh soft-tissue tumors, with a historical cohort of 20 patients.[

References:

- Paramanandam VS, Dylke E, Clark GM, et al.: Prophylactic Use of Compression Sleeves Reduces the Incidence of Arm Swelling in Women at High Risk of Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol 40 (18): 2004-2012, 2022.

- Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel AB, et al.: Weight lifting for women at risk for breast cancer-related lymphedema: a randomized trial. JAMA 304 (24): 2699-705, 2010.

- Paskett ED, Le-Rademacher J, Oliveri JM, et al.: A randomized study to prevent lymphedema in women treated for breast cancer: CALGB 70305 (Alliance). Cancer 127 (2): 291-299, 2021.

- Naughton MJ, Liu H, Seisler DK, et al.: Health-related quality of life outcomes for the LEAP study-CALGB 70305 (Alliance): A lymphedema prevention intervention trial for newly diagnosed breast cancer patients. Cancer 127 (2): 300-309, 2021.

- Devoogdt N, Geraerts I, Van Kampen M, et al.: Manual lymph drainage may not have a preventive effect on the development of breast cancer-related lymphoedema in the long term: a randomised trial. J Physiother 64 (4): 245-254, 2018.

- Blom KY, Johansson KI, Nilsson-Wikmar LB, et al.: Early intervention with compression garments prevents progression in mild breast cancer-related arm lymphedema: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Oncol 61 (7): 897-905, 2022.

- Dayes IS, Whelan TJ, Julian JA, et al.: Randomized trial of decongestive lymphatic therapy for the treatment of lymphedema in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 31 (30): 3758-63, 2013.

- Kilbreath SL, Ward LC, Davis GM, et al.: Reduction of breast lymphoedema secondary to breast cancer: a randomised controlled exercise trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 184 (2): 459-467, 2020.

- Schmitz KH, Troxel AB, Dean LT, et al.: Effect of Home-Based Exercise and Weight Loss Programs on Breast Cancer-Related Lymphedema Outcomes Among Overweight Breast Cancer Survivors: The WISER Survivor Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 5 (11): 1605-1613, 2019.

- Dionyssiou D, Demiri E, Tsimponis A, et al.: A randomized control study of treating secondary stage II breast cancer-related lymphoedema with free lymph node transfer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 156 (1): 73-9, 2016.

- Wang X, Ding Y, Cai HY, et al.: Effectiveness of modified complex decongestive physiotherapy for preventing lower extremity lymphedema after radical surgery for cervical cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Gynecol Cancer 30 (6): 757-763, 2020.

- Shallwani SM, Towers A, Newman A, et al.: Feasibility of a Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial Examining a Multidimensional Intervention in Women with Gynecological Cancer at Risk of Lymphedema. Curr Oncol 28 (1): 455-470, 2021.

- Liao SF, Li SH, Huang HY: The efficacy of complex decongestive physiotherapy (CDP) and predictive factors of response to CDP in lower limb lymphedema (LLL) after pelvic cancer treatment. Gynecol Oncol 125 (3): 712-5, 2012.

- Tyker A, Franco J, Massa ST, et al.: Treatment for lymphedema following head and neck cancer therapy: A systematic review. Am J Otolaryngol 40 (5): 761-769, 2019.

- Ozdemir K, Keser I, Duzlu M, et al.: The Effects of Clinical and Home-based Physiotherapy Programs in Secondary Head and Neck Lymphedema. Laryngoscope 131 (5): E1550-E1557, 2021.

- Ridner SH, Dietrich MS, Deng J, et al.: Advanced pneumatic compression for treatment of lymphedema of the head and neck: a randomized wait-list controlled trial. Support Care Cancer 29 (2): 795-803, 2021.

- Alamoudi U, Taylor B, MacKay C, et al.: Submental liposuction for the management of lymphedema following head and neck cancer treatment: a randomized controlled trial. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 47 (1): 22, 2018.

- Wagner JM, Dadras M, Ufton D, et al.: Prophylactic lymphaticovenous anastomoses for resection of soft tissue tumors of the thigh to prevent secondary lymphedema-a retrospective comparative cohort analysis. Microsurgery 42 (3): 239-245, 2022.

Latest Updates to This Summary (12 / 18 / 2024)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

Added

This summary is written and maintained by the

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the diagnosis and treatment of lymphedema. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Lymphedema are:

- Larry D. Cripe, MD (Indiana University School of Medicine)

- James T. Pastrnak, MD (Indiana University School of Medicine)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board uses a

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board. PDQ Lymphedema. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at:

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our

Last Revised: 2024-12-18

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the

Healthwise, Healthwise for every health decision, and the Healthwise logo are trademarks of Ignite Healthwise, LLC.

Page Footer

I want to...

Audiences

Secure Member Sites

The Cigna Group Information

Disclaimer

Individual and family medical and dental insurance plans are insured by Cigna Health and Life Insurance Company (CHLIC), Cigna HealthCare of Arizona, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Illinois, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of Georgia, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of North Carolina, Inc., Cigna HealthCare of South Carolina, Inc., and Cigna HealthCare of Texas, Inc. Group health insurance and health benefit plans are insured or administered by CHLIC, Connecticut General Life Insurance Company (CGLIC), or their affiliates (see

All insurance policies and group benefit plans contain exclusions and limitations. For availability, costs and complete details of coverage, contact a licensed agent or Cigna sales representative. This website is not intended for residents of New Mexico.