Evidence of Benefit Associated With Screening

No population-based screening programs for oral cavity squamous cell cancers have been implemented in developed countries, although opportunistic screening or screening as part of a periodic health examination has been advocated for the oral cavity, which is the only site accessible without endoscopy.[1,2]

Screening for Oral Cavity Cancers

There are different methods of screening for oral cavity cancers. Oral cavity cancers occur in a region of the body that is generally accessible to physical examination by the patient, the dentist, and the physician. Visual examination is the most common method used to detect visible lesions. Other methods have been used to augment clinical detection of oral lesions and include toluidine blue, brush biopsy, and fluorescence staining.

An inspection of the oral cavity is often part of a physical examination in a dentist's or physician's office. Of note, high-risk individuals visit their medical doctors more frequently than they visit their dentists. Although physicians are more likely to provide risk-factor counseling (such as tobacco cessation), they are less likely than dentists to perform an oral cancer examination.[3] Overall, only a fraction (~20%) of Americans receive an oral cancer examination. Black patients, Hispanic patients, and those who have a lower level of education are less likely to have such an examination, perhaps because they lack access to medical care.[3] An oral examination often includes looking for leukoplakia and erythroplakia lesions, which can progress to cancer.[4,5] One study has shown that direct fluorescence visualization (using a simple hand-held device in the operating room) could identify subclinical high-risk fields with cancerous or precancerous changes extending up to 25 mm beyond the primary tumor in 19 of 20 patients undergoing oral surgery for invasive or in situ squamous cell tumors.[6] However, this finding has not yet been tested in a screening setting. Data suggest that molecular markers may be useful in the prognosis of these premalignant oral lesions.[7]

The routine examination of asymptomatic and symptomatic patients can lead to detection of earlier-stage cancers and premalignant lesions. There is no definitive evidence, however, to show that this screening can reduce oral cancer mortality, and there are no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in any Western or other low-risk populations.[5,8,9,10,11]

In a single RCT of screening versus usual care, 13 geographic clusters in the Trivandrum district of Kerala, India, were randomly assigned to receive systematic oral visual screening by trained health workers (seven screened clusters, six control clusters) every 3 years for four screening rounds between 1996 and 2008. During a 15-year follow-up period, there were 138 deaths from oral cancer in the screening group, with a cause-specific mortality rate of 15.4 per 100,000 person-years, and 154 deaths in the control group, with a mortality rate of 17.1 per 100,000 person-years (relative risk [RR], 0.88; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.69–1.12). In a subset analysis restricted to tobacco or alcohol users, the mortality rates were 30 and 39 per 100,000 person-years, respectively (RR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.60–0.97). There was no apparent adjustment of the CIs for the cluster design. In another subgroup analysis, mortality hazard ratios were calculated for groups defined by number of times screened, but the inappropriate comparison in each case was to the control group of the whole study. No data on treatment of oral cancers were presented.[12,13,14,15]

Aside from the issues of generalizability to other populations and lack of an overall statistically significant result in cause-specific mortality, interpretation of the results is made difficult by serious lacks in methodological detail about the randomization process, allocation concealment, adjustment for clustering effect, and information about treatment. The total number of clusters randomized was small, and there were different distributions of income and household possessions between the two study arms. Withdrawals and dropouts were not clearly described. In summary, the sole randomized trial does not provide solid evidence of a cause-specific mortality benefit associated with systematic oral cavity visual examination.

Techniques such as toluidine blue staining, brush biopsy/cytology, or fluorescence imaging as the primary screening tool or as an adjunct for screening have not been shown to have superior sensitivity and specificity for visual examination alone or to yield better health outcomes.[5,16] In an RCT conducted in Keelung County, Taiwan, 7,975 individuals at high risk of oral cancer due to cigarette smoking or betel-quid chewing were randomly assigned to receive a one-time oral cancer examination after gargling with toluidine blue or a blue placebo dye.[17] The positive test rates were 9.5% versus 8.3%, respectively (P = .047). The detection of premalignant lesions was not statistically different (rate ratio, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.74–1.41). The number of overall oral cancers diagnosed within the short follow-up period of 5 years was too small for valid comparison (six in each group).

The operating characteristics of the various techniques used as an adjunct to oral visual examination are not well established. A systematic literature review of toluidine blue, a variety of other visualization adjuncts, and cytopathology in the screening setting revealed a very broad range of reported sensitivities, specificities, and positive predictive values when biopsy confirmation was used as the gold standard outcome.[18] In part, this range of findings can be attributed to varying study populations, sample size and settings, and criteria for positive-clinical examinations and for scoring a biopsy as positive.

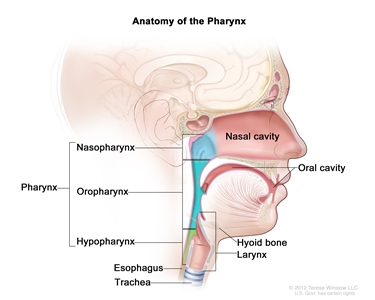

Screening for Nasopharyngeal Cancer

Serum Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)–associated antibodies and circulating cell-free EBV DNA testing have been used for nasopharyngeal cancer diagnosis and screening. In an observational study of 20,349 men aged 40 to 62 years, circulating cell-free EBV DNA testing was used to screen for nasopharyngeal cancer.[19,20] A total of 1.5% of participants tested positive twice for EBV DNA and had further workup, leading to a diagnosis of nasopharyngeal cancer for 34 patients. The EBV DNA test had a sensitivity of 97.1% (95% CI, 95.5%–98.7%) and specificity of 98.6% (95% CI, 98.6%–98.7%). Without a control group, the study compared stage of disease at diagnosis with a historical cohort and found a higher proportion of stage I and stage II disease (71% vs. 20%; P < .001) and superior 3-year progression-free survival in the screen-detected population. However, the survival benefit in the study may also be caused by lead-time bias.

Other screening programs in southern China use EBV-associated antibodies, but their effects are difficult to determine because of lack of controls for comparison of survival outcomes.[20,21,22] In summary, current screening studies for nasopharyngeal cancer do not provide solid evidence of a benefit associated with screening for nasopharyngeal cancer, especially in nonendemic regions such as the United States.

References:

- Opportunistic oral cancer screening: a management strategy for dental practice. BDA Occasional Paper 6: 1-36, 2000. Also available online. Last accessed April 14, 2025.

- Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brooks D, et al.: Cancer screening in the United States, 2011: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin 61 (1): 8-30, 2011 Jan-Feb.

- Kerr AR, Changrani JG, Gany FM, et al.: An academic dental center grapples with oral cancer disparities: current collaboration and future opportunities. J Dent Educ 68 (5): 531-41, 2004.

- Warnakulasuriya S, Johnson NW, van der Waal I: Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med 36 (10): 575-80, 2007.

- Brocklehurst P, Kujan O, Glenny AM, et al.: Screening programmes for the early detection and prevention of oral cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (11): CD004150, 2010.

- Poh CF, Zhang L, Anderson DW, et al.: Fluorescence visualization detection of field alterations in tumor margins of oral cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res 12 (22): 6716-22, 2006.

- Poh CF, Zhang L, Lam WL, et al.: A high frequency of allelic loss in oral verrucous lesions may explain malignant risk. Lab Invest 81 (4): 629-34, 2001.

- Screening for oral cancer. In: Fisher M, Eckhart C, eds.: Guide to Clinical Preventive Services: an Assessment of the Effectiveness of 169 Interventions. Report of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Williams & Wilkins, 1989, pp 91-94.

- Antunes JL, Biazevic MG, de Araujo ME, et al.: Trends and spatial distribution of oral cancer mortality in São Paulo, Brazil, 1980-1998. Oral Oncol 37 (4): 345-50, 2001.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force: Screening for Oral Cancer: Recommendation Statement. Rockville, Md: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2013. Available online. Last accessed April 14, 2025.

- Scattoloni J: Screening for Oral Cancer: Brief Evidence Update. Rockville, Md: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 2004. Available online. Last accessed April 14, 2025.

- Sankaranarayanan R, Mathew B, Jacob BJ, et al.: Early findings from a community-based, cluster-randomized, controlled oral cancer screening trial in Kerala, India. The Trivandrum Oral Cancer Screening Study Group. Cancer 88 (3): 664-73, 2000.

- Ramadas K, Sankaranarayanan R, Jacob BJ, et al.: Interim results from a cluster randomized controlled oral cancer screening trial in Kerala, India. Oral Oncol 39 (6): 580-8, 2003.

- Sankaranarayanan R, Ramadas K, Thomas G, et al.: Effect of screening on oral cancer mortality in Kerala, India: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 365 (9475): 1927-33, 2005 Jun 4-10.

- Sankaranarayanan R, Ramadas K, Thara S, et al.: Long term effect of visual screening on oral cancer incidence and mortality in a randomized trial in Kerala, India. Oral Oncol 49 (4): 314-21, 2013.

- Lingen MW, Kalmar JR, Karrison T, et al.: Critical evaluation of diagnostic aids for the detection of oral cancer. Oral Oncol 44 (1): 10-22, 2008.

- Su WW, Yen AM, Chiu SY, et al.: A community-based RCT for oral cancer screening with toluidine blue. J Dent Res 89 (9): 933-7, 2010.

- Patton LL, Epstein JB, Kerr AR: Adjunctive techniques for oral cancer examination and lesion diagnosis: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Dent Assoc 139 (7): 896-905; quiz 993-4, 2008.

- Chan KCA, Woo JKS, King A, et al.: Analysis of Plasma Epstein-Barr Virus DNA to Screen for Nasopharyngeal Cancer. N Engl J Med 377 (6): 513-522, 2017.

- Cao SM, Simons MJ, Qian CN: The prevalence and prevention of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in China. Chin J Cancer 30 (2): 114-9, 2011.

- Zeng Y, Zhang LG, Li HY, et al.: Serological mass survey for early detection of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Wuzhou City, China. Int J Cancer 29 (2): 139-41, 1982.

- Zeng Y, Zhong JM, Li LY, et al.: Follow-up studies on Epstein-Barr virus IgA/VCA antibody-positive persons in Zangwu County, China. Intervirology 20 (4): 190-4, 1983.