Overview

Note: The Overview section summarizes the published evidence on this topic. The rest of the summary describes the evidence in more detail.

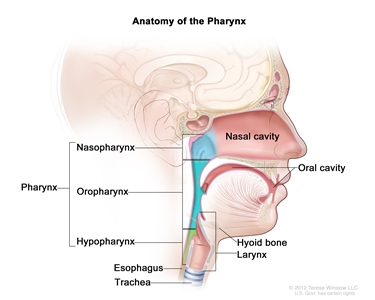

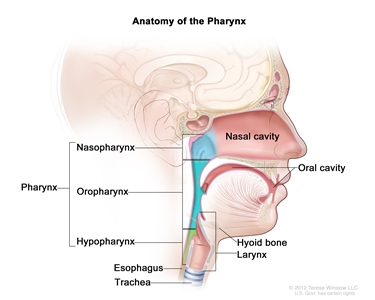

Oral cavity, oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers may be referred to as head and neck squamous cell cancers. Head and neck squamous cell cancers most commonly arise from the mucosal surfaces lining the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx. Anatomically, the pharynx includes the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and hypopharynx, but cancers in these sites have distinct clinical and epidemiologic characteristics. Thus, it is inappropriate to group them together.[1] For more information, see the following PDQ summaries:

- Laryngeal Cancer Treatment

- Lip and Oral Cavity Cancer Treatment

- Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Treatment

- Oropharyngeal Cancer Treatment

Figure 1 shows the anatomy of the pharynx.

Figure 1. Anatomy of the pharynx.

Who Is at Risk?

Head and neck squamous cell cancers have common risk factors. People who use tobacco in any of the commonly available forms (cigarettes, cigars, pipes, and smokeless tobacco) or have a high alcohol intake are at elevated risk of oral cavity, oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers; they are at particularly high risk if they use both tobacco and alcohol.[2] Individuals who chew betel quid (whether mixed with tobacco or not) are also at high risk of cancer of the oral cavity and oropharynx.[3,4] Individuals who have a personal history of cancer of the head and neck region also are at elevated risk of a future primary cancer of the head and neck.[5] Human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV-16) is a sufficient, but not necessary, cause of oral, tongue, and oropharyngeal cancers.[2,6]

Note: Separate PDQ summaries on Oral Cavity and Nasopharyngeal Cancers Screening and Cigarette Smoking: Health Risks and How to Quit are also available.

Factors With Adequate Evidence of an Increased Risk of Oral Cavity, Oropharyngeal, Hypopharyngeal, and Laryngeal Cancers

Tobacco use

Based on solid evidence from numerous observational studies, tobacco use increases the risk of cancers of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx.[7,8,9]

Magnitude of Effect: Large. Risk for current smokers ranges from fourfold to fivefold for oral cavity, oropharyngeal, and hypopharyngeal cancers to tenfold for laryngeal cancer compared with never-smokers, and is dose related. Most cancers of the oral cavity, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx are attributable to the use of tobacco products.

| Study Design: Case-control and cohort studies. |

| Internal Validity: Good. |

| Consistency: Good. |

| External Validity: Good. |

Alcohol use

Based on solid evidence, alcohol use is a risk factor for the development of head and neck cancers. Its effects are independent of those of tobacco use.[9,10,11,12]

Magnitude of Effect: Lower than the risk associated with tobacco use, but the risk is approximately twofold to sixfold for people who drink two or more alcoholic beverages per day compared with nondrinkers, and is dose related.

| Study Design: Case-control and cohort studies. |

| Internal Validity: Good. |

| Consistency: Good. |

| External Validity: Good. |

Tobacco and alcohol use

The risk of oral cavity, oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers is highest in people who consume large amounts of both alcohol and tobacco. When both risk factors are present, the risk of cancer is greater than a simple multiplicative effect of the two individual risks.[13,14,15]

Magnitude of Effect: About two to three times greater for oral cavity, oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers than the simple multiplicative effect, with risks for persons who both smoke and drink heavily approximately 5- to 14-fold that of persons who both never smoke and never drink.

| Study Design: Case-control and cohort studies. |

| Internal Validity: Good. |

| Consistency: Good. |

| External Validity: Good. |

Betel-quid chewing

Based on solid evidence, chewing betel quid alone or with added tobacco increases the risk of both oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers.[3,4] Of the three primary components of betel quid (betel leaf, areca nut, and lime), the areca nut is the only one considered to be carcinogenic when chewed.

Magnitude of Effect: Relative risks for oral cavity cancer are high and typically stronger for betel quid with tobacco than for betel quid alone. Both products appear to confer a statistically significant increase in risk of oropharyngeal cancer.[4]

| Study Design: Case-control, and cohort studies. |

| Internal Validity: Good. |

| Consistency: Good. |

| External Validity: Good. |

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection

Based on solid evidence, HPV type 16 (HPV-16) infection causes oropharyngeal cancer.[6,16] Other high-risk HPV subtypes, including HPV type 18 (HPV-18), have been found in a small percentage of oropharyngeal cancers.[17,18]

Magnitude of Effect: Large. Oral infection with HPV-16 confers about a 15-fold increase in risk of oropharyngeal cancer relative to individuals without oral HPV-16 infection.

| Study Design: Case-control and cohort studies. |

| Internal Validity: Good. |

| Consistency: Good. |

| External Validity: Good. |

Interventions With Adequate Evidence of a Decreased Risk of Oral Cavity, Oropharyngeal, Hypopharyngeal, and Laryngeal Cancers

Tobacco cessation

Based on solid evidence, cessation of exposure to tobacco (e.g., cigarettes, pipes, cigars, and smokeless tobacco) leads to a decrease in the risk of oral cavity, oropharyngeal, hypopharyngeal, and laryngeal cancers.[19]

Magnitude of Effect: Decreased risk, moderate to large magnitude.

| Study Design: Case-control and cohort studies. |

| Internal Validity: Good. |

| Consistency: Good. |

| External Validity: Good. |

Interventions With Inadequate Evidence of a Reduced Risk of Oral Cavity, Oropharyngeal, Hypopharyngeal, and Laryngeal Cancers

Cessation of alcohol consumption

Based on fair evidence, cessation of alcohol consumption leads to a decrease in oral cavity and laryngeal cancer risk 20 years or more after cessation.[19]

Magnitude of Effect: Decreased risk, small to moderate magnitude.

| Study Design: Case-control studies. |

| Internal Validity: Fair. |

| Consistency: Fair. |

| External Validity: Fair. |

Vaccination against HPV-16 and the other high-risk subtypes

Vaccination against HPV-16 and HPV-18 has been shown to prevent approximately 90% of oral HPV-16/HPV-18 infections within 4 years of vaccination.[20] However, no data are available to assess whether vaccination at any age will lead to reduced risk of oropharyngeal cancer at current typical ages of diagnosis.[21]

| Study Design: No studies available. |

| Internal Validity: Not applicable (N/A). |

| Consistency: N/A. |

| External Validity: N/A. |

References:

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Personal habits and indoor combustions. Volume 100 E. A review of human carcinogens. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 100 (Pt E): 1-538, 2012.

- Castellsagué X, Alemany L, Quer M, et al.: HPV Involvement in Head and Neck Cancers: Comprehensive Assessment of Biomarkers in 3680 Patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 108 (6): djv403, 2016.

- Song H, Wan Y, Xu YY: Betel quid chewing without tobacco: a meta-analysis of carcinogenic and precarcinogenic effects. Asia Pac J Public Health 27 (2): NP47-57, 2015.

- Guha N, Warnakulasuriya S, Vlaanderen J, et al.: Betel quid chewing and the risk of oral and oropharyngeal cancers: a meta-analysis with implications for cancer control. Int J Cancer 135 (6): 1433-43, 2014.

- Atienza JA, Dasanu CA: Incidence of second primary malignancies in patients with treated head and neck cancer: a comprehensive review of literature. Curr Med Res Opin 28 (12): 1899-909, 2012.

- Kreimer AR, Johansson M, Waterboer T, et al.: Evaluation of human papillomavirus antibodies and risk of subsequent head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol 31 (21): 2708-15, 2013.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014. Also available online. Last accessed December 30, 2024.

- Vineis P, Alavanja M, Buffler P, et al.: Tobacco and cancer: recent epidemiological evidence. J Natl Cancer Inst 96 (2): 99-106, 2004.

- Hashibe M, Brennan P, Benhamou S, et al.: Alcohol drinking in never users of tobacco, cigarette smoking in never drinkers, and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst 99 (10): 777-89, 2007.

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Smokeless tobacco and some tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 89: 1-592, 2007.

- Purdue MP, Hashibe M, Berthiller J, et al.: Type of alcoholic beverage and risk of head and neck cancer--a pooled analysis within the INHANCE Consortium. Am J Epidemiol 169 (2): 132-42, 2009.

- Islami F, Tramacere I, Rota M, et al.: Alcohol drinking and laryngeal cancer: overall and dose-risk relation--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Oncol 46 (11): 802-10, 2010.

- Hashibe M, Brennan P, Chuang SC, et al.: Interaction between tobacco and alcohol use and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18 (2): 541-50, 2009.

- Lubin JH, Purdue M, Kelsey K, et al.: Total exposure and exposure rate effects for alcohol and smoking and risk of head and neck cancer: a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol 170 (8): 937-47, 2009.

- Mello FW, Melo G, Pasetto JJ, et al.: The synergistic effect of tobacco and alcohol consumption on oral squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Oral Investig 23 (7): 2849-2859, 2019.

- Hobbs CG, Sterne JA, Bailey M, et al.: Human papillomavirus and head and neck cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Otolaryngol 31 (4): 259-66, 2006.

- D'Souza G, Kreimer AR, Viscidi R, et al.: Case-control study of human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med 356 (19): 1944-56, 2007.

- Steinau M, Saraiya M, Goodman MT, et al.: Human papillomavirus prevalence in oropharyngeal cancer before vaccine introduction, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 20 (5): 822-8, 2014.

- Marron M, Boffetta P, Zhang ZF, et al.: Cessation of alcohol drinking, tobacco smoking and the reversal of head and neck cancer risk. Int J Epidemiol 39 (1): 182-96, 2010.

- Herrero R, Quint W, Hildesheim A, et al.: Reduced prevalence of oral human papillomavirus (HPV) 4 years after bivalent HPV vaccination in a randomized clinical trial in Costa Rica. PLoS One 8 (7): e68329, 2013.

- Chaturvedi AK, Graubard BI, Broutian T, et al.: Effect of Prophylactic Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination on Oral HPV Infections Among Young Adults in the United States. J Clin Oncol 36 (3): 262-267, 2018.