Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage

Plans through your employer

Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

Learn

Living or working abroad?

Planning the Transition to End-of-Life Care in Advanced Cancer (PDQ®): Supportive care - Health Professional Information [NCI]

Overview

The American Cancer Society estimates that 618,120 Americans will die of cancer in 2025.[

- Increased psychological distress.

- Medical treatments inconsistent with personal preferences.

- Utilization of burdensome and expensive health care resources of little therapeutic benefit.

- A more difficult bereavement.

Oncologists and patients often avoid or delay planning for the EOL until the final weeks or days of life because of many potential factors. These factors can be at the individual, family, or societal levels. Evidence suggests, however, that many of these factors are not truly barriers and can be overcome.

The purpose of this summary is to review the evidence surrounding conversations about EOL care in advanced cancer to inform providers, patients, and families about the transition to compassionate and effective EOL care.

References:

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. American Cancer Society, 2025.

Available online . Last accessed January 16, 2025.

Quality of End-of-Life Care in Patients With Advanced Cancer

Patients with advanced cancer, their family and friends, and oncology clinicians often are faced with treatment decisions that profoundly affect the patient's quality of life (QOL). Oncology clinicians are obligated to explore, with the patient and family, the potential impact of continued disease-directed treatments or care directed at the patient's symptoms and QOL.

This section summarizes information that will allow oncology clinicians and patients with advanced cancer to create a plan of care to improve QOL at the end of life (EOL) by making informed choices about the potential harms of continued aggressive treatment and the potential benefits of palliative or hospice care. This section:

- Reviews the concept of quality EOL care.

- Summarizes and evaluates the commonly cited indicators of quality EOL care.

- Explores the concept of a good death.

In addition, information about outcomes associated with cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) at the EOL will allow the oncology clinician to better present options to patients with advanced cancer who are near the EOL.

Quality of EOL Care

Questions relevant to measuring the quality of EOL care in patients with advanced cancer include the following:[

- Which evidence-based guidelines inform assessments of quality?

- What period defines the EOL?

- Are the quality indicators of interest accurate, readily available, and plausibly linked to desired outcomes?

- What constitutes high quality?

- Most important, is the patient's perspective given precedence?

The patient perspective

Surveys and interviews of patients with life-threatening illnesses, not restricted to cancer, can contribute to the understanding of what constitutes high-quality EOL care. One group of researchers proposed that patients value five main domains of care near the EOL:[

- Receiving adequate pain and symptom management.

- Avoiding inappropriate prolongation of dying.

- Achieving a sense of control.

- Relieving burden.

- Strengthening relationships with loved ones.

A 2011 prospective study of QOL in a cohort of patients with advanced cancer seen in outpatient medical oncology clinics provides additional insight into the patient's perspective of what contributes to a good QOL.[

- Older age.

- Good performance status.

- A survival time longer than 6 months.

Patients who were waiting for a new treatment had worse emotional well-being. This experience suggests that QOL is related to factors such as disease progression and its complications, and to patients' goals relative to any treatment they are receiving.[

Indicators of EOL care quality

A variety of indicators have been proposed to measure the quality of EOL care in patients with advanced cancer. Several salient criticisms of the proposed indicators include the following:

- Indicators are typically measured in a period before death that is defined retrospectively from death. Clinicians cannot predict whether an intervention will be futile in preventing death; consequently, quality concerns may be exaggerated if the indicator is dependent on the time to death.

- Quality indicators may be insensitive to patient preferences. For example, a patient may prefer to receive chemotherapy close to death and forgo hospice enrollment. Conversely, the failure to deliver treatments consistent with guidelines may reflect patient refusals or medical contraindications to the recommended treatment. One study [

5 ] demonstrated that adherence to six quality indicators in patients with lung cancer cared for in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) was compromised by refusal (0%—14% of the time) or medical contraindications (1%—30% of the time), depending on the indicator. - Administrative databases do not capture data for all patients. For example, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services databases capture only the Medicare population.

- Many indicators were not deliberately developed as measures of quality and may be insensitive to important outcomes.

Nonetheless, studying indicators over time or between different geographic regions, health systems, or subspecialties can provide important insights into quality EOL care.

Trends over time in indicators of EOL care quality

Multiple reports are relevant to understanding trends in EOL care quality indicators over time for a variety of cancers. The following observations are supported by a 2004 analysis,[

- Increasing numbers of patients start a new chemotherapy regimen within 30 days of death or continue to receive chemotherapy within 14 days of death.

- Increasing numbers of patients are referred to hospice; however, the length of stay in hospice remains relatively brief, supporting the concern that referrals to hospice may occur too late. For example, a 2011 study of men dying of prostate cancer demonstrated an increased utilization of hospice (approximately 32%–60%), but there was also an increase in the proportion of stays shorter than 7 days.[

7 ] - The rates of utilization of ICU stays have also increased. For example, one study [

8 ] reported that for patients dying of pancreatic cancer, admissions to ICUs increased in two different time periods. From 1992 to 1994, ICU admissions increased from 15.5% to 19.6%; from 2004 to 2006, ICU admissions increased from 8.1% to 16.4%. - Rates of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders have increased but remain close to death. A 2008 study of the rate and timing of DNR orders at a major cancer center between 2000 and 2005 demonstrated that the rates of DNR orders at the time of death increased from 83% to 86% for in-hospital deaths and from 28% to 52% for out-of-hospital deaths.[

9 ] However, for inpatient deaths, the median time between signing the DNR and death was 0 days; for outpatient deaths, it was 30 days. This finding suggests that communication about resuscitation preferences is delayed. This delay may negatively affect patient preparation for the EOL.

Regional variations in indicators of EOL care quality

Regional variations in rates of utilization of health care resources near the EOL are of interest because the differences are rarely associated with improved outcomes. While initial findings focused on differences between geographic regions of the United States, subsequent studies have demonstrated potentially meaningful differences between or within health systems.[

- Compared with men enrolled in a fee-for-service Medicare product, older men with advanced cancer who received treatment through the VHA were less likely to receive chemotherapy within 14 days of death (4.6% vs. 7.5%), less likely to spend time in an ICU within 30 days of death (12.5% vs. 19.7%), and less likely to visit the emergency department more than once (13.1% vs. 14.7%).[

11 ] - An analysis of data by the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice about the care of Medicare patients with poor prognoses demonstrated significant regional variations in EOL care.[

12 ] The principal findings include the following:- Variations in the rate of hospitalizations, ICU stays, and aggressive interventions such as CPR and mechanical ventilation.

- Variations in the use of chemotherapy in the last 14 days of life.

- Variations in the use of hospice measured as rates of referral or lengths of stay.

In the opinion of the authors, the observed regional variations were too large to be accounted for by racial or ethnic preferences or illness levels. Factors correlated with the aggressiveness of EOL care include the availability of resources such as the supply of ICU beds or imaging equipment, the number of doctors involved in each patient's care, and the treatment setting itself.[

12 ]

Factors associated with variations in EOL care

Availability of medical specialists, number of hospital beds, physician, and health system characteristics are well-established factors associated with increased expenditures in the final 6 months of life. A 2011 study [

- Functional status decline.

- Hispanic ethnicity.

- Black race.

- Chronic diseases such as diabetes.

Patient-level factors accounted for only 10% of variations. EOL practice patterns and number of hospital beds per capita were also associated with higher expenditures. Advance care planning did not influence expenditures.[

A potential explanation for regional variations in EOL care is regional variations in patient preferences. The evidence, however, is conflicting.

- One study surveyed 2,515 Medicare beneficiaries about their general preferences for medical care in the event of a serious life-limiting illness with a life expectancy of less than 1 year.[

14 ] The preferences were correlated with EOL spending by hospital referral region. There were no differences between preferences for palliation or life prolongation by region. Thus, it is unlikely that regional variations in preferences account for observed variation in EOL spending. - Conversely, a secondary analysis of the potential influence of treatment site on the Coping with Cancer study outcomes demonstrated that the effect of treatment site partly resulted from differences in patient preferences.[

15 ]

The Good Death

The health care provider perspective

The concept of a good death is a controversial but potentially useful construct for the oncology clinician to more clearly formulate the goals of timely, compassionate, and effective EOL care. In a 2003 BMJ article about caring for the dying patient, the authors proposed that there were sufficient evidence-based guidelines to facilitate a good death. A commentary that accompanied the article stated, "Nor can professional education convey adequately just how important it is for individuals, both at the time and afterwards, to go through the death of someone they love feeling that they are experiencing a ‘good death.'"[

- The mental health of the patient and family are essential concerns in providing a good death.

- Health care provider beliefs and attitudes may diminish the chances for a good death if they interfere with adequate pain or symptom control.

- Health care providers may risk medical paternalism if they are not respectful of a patient's perspective and insist on EOL care or refuse to provide comfort measures that may shorten life.

- Religious faith and spiritual beliefs are important for many people near the EOL.

- A good death requires turning one's attention away from prolonging life.

The patient perspective

A landmark study of patients, families, and health care providers [

Patients with advanced cancer may desire opportunities to prepare for the EOL. A survey of 469 patients who participated in a cluster-randomized trial of early palliative care [

The caregiver perspective

In one study,[

- Intensive care in the last week.

- Death in the hospital.

- Feeding tube in the final week.

- Chemotherapy in the final week of life.

Conversely, factors correlated with a higher QOL included the following:

- Prayer or meditation.

- Visits with chaplains.

- The perception that the physician was respectful, open to questions, and trustworthy.

Outcomes After Potentially Life-Prolonging Interventions

CPR

CPR was initially developed to restore circulation in patients with predominantly cardiac insults. The outcomes after inpatient CPR in older adults have not improved significantly, in part because of the use of CPR in patients with comorbid life-threatening illnesses. Addressing the limited benefit of CPR during the transition to EOL care is made more difficult because in the United States, patients will undergo CPR unless there is an established DNR order in the medical chart to countermand the procedure. The following evidence demonstrates the limited value of CPR in patients with advanced cancer:

- A retrospective chart review of 41 patients who underwent CPR for an out-of-hospital cardiac arrest found that only 18 (43%) survived to be admitted to an ICU, and only 9 patients survived to be discharged (2 to home; 7 to a facility).[

22 ] The authors noted that documentation of the advanced stage of disease and poor prognosis were frequently mentioned in the medical records. - A meta-analysis of studies of survival after in-hospital CPR found that survival to discharge was 6.2% overall.[

23 ] Patients with advanced-stage disease and hematological malignancy who underwent CPR in the ICU were less likely to survive. - Researchers have described the extremely poor outcomes of patients who were resuscitated in the medical ICU.[

24 ,25 ] Only 7 of 406 patients resuscitated (2%) survived to be discharged. The remainder died at the time of the arrest (63%) or within a mean of 4 days (26%).

Admission to an ICU

In addition to CPR, patients may require mechanical ventilation or admission to an ICU. Outcomes are poor for patients with advanced cancer. One study reported that the median survival of 212 patients with advanced cancer (who were referred to a phase I trial) was 3.2 weeks.[

The underlying diagnosis, however, may be a critical variable in predicting patient outcome. Patients with hematologic malignancies may do better than patients with solid tumors. For example, one study reported that patients with newly diagnosed hematologic malignancies had a 60.7% chance of surviving to be discharged and a 1-year survival rate of 43.3%.[

References:

- Kendall M, Harris F, Boyd K, et al.: Key challenges and ways forward in researching the "good death": qualitative in-depth interview and focus group study. BMJ 334 (7592): 521, 2007.

- Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M: Quality end-of-life care: patients' perspectives. JAMA 281 (2): 163-8, 1999.

- Zimmermann C, Burman D, Swami N, et al.: Determinants of quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 19 (5): 621-9, 2011.

- Jones JM, McPherson CJ, Zimmermann C, et al.: Assessing agreement between terminally ill cancer patients' reports of their quality of life and family caregiver and palliative care physician proxy ratings. J Pain Symptom Manage 42 (3): 354-65, 2011.

- Ryoo JJ, Ordin DL, Antonio AL, et al.: Patient preference and contraindications in measuring quality of care: what do administrative data miss? J Clin Oncol 31 (21): 2716-23, 2013.

- Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al.: Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol 22 (2): 315-21, 2004.

- Bergman J, Saigal CS, Lorenz KA, et al.: Hospice use and high-intensity care in men dying of prostate cancer. Arch Intern Med 171 (3): 204-10, 2011.

- Sheffield KM, Boyd CA, Benarroch-Gampel J, et al.: End-of-life care in Medicare beneficiaries dying with pancreatic cancer. Cancer 117 (21): 5003-12, 2011.

- Levin TT, Li Y, Weiner JS, et al.: How do-not-resuscitate orders are utilized in cancer patients: timing relative to death and communication-training implications. Palliat Support Care 6 (4): 341-8, 2008.

- Newhouse JP, Garber AM: Geographic variation in health care spending in the United States: insights from an Institute of Medicine report. JAMA 310 (12): 1227-8, 2013.

- Keating NL, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al.: End-of-life care for older cancer patients in the Veterans Health Administration versus the private sector. Cancer 116 (15): 3732-9, 2010.

- Goodman DC, Morden NE, Chang CH, et al.: Trends in Cancer Care Near the End of Life: A Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care Brief. Lebanon, NH: Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy & Clinical Practice, 2013.

Available online . Last accessed Jan. 23, 2025. - Kelley AS, Ettner SL, Morrison RS, et al.: Determinants of medical expenditures in the last 6 months of life. Ann Intern Med 154 (4): 235-42, 2011.

- Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, et al.: Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences?: A Study of the US Medicare Population. Med Care 45 (5): 386-93, 2007.

- Wright AA, Mack JW, Kritek PA, et al.: Influence of patients' preferences and treatment site on cancer patients' end-of-life care. Cancer 116 (19): 4656-63, 2010.

- Ellershaw J, Ward C: Care of the dying patient: the last hours or days of life. BMJ 326 (7379): 30-4, 2003.

- Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al.: Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA 284 (19): 2476-82, 2000.

- Rietjens JA, van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, et al.: Preferences of the Dutch general public for a good death and associations with attitudes towards end-of-life decision-making. Palliat Med 20 (7): 685-92, 2006.

- Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, et al.: Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 383 (9930): 1721-30, 2014.

- Wentlandt K, Burman D, Swami N, et al.: Preparation for the end of life in patients with advanced cancer and association with communication with professional caregivers. Psychooncology 21 (8): 868-76, 2012.

- Zhang B, Nilsson ME, Prigerson HG: Factors important to patients' quality of life at the end of life. Arch Intern Med 172 (15): 1133-42, 2012.

- Hwang JP, Patlan J, de Achaval S, et al.: Survival in cancer patients after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Support Care Cancer 18 (1): 51-5, 2010.

- Reisfield GM, Wallace SK, Munsell MF, et al.: Survival in cancer patients undergoing in-hospital cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a meta-analysis. Resuscitation 71 (2): 152-60, 2006.

- Ewer MS, Kish SK, Martin CG, et al.: Characteristics of cardiac arrest in cancer patients as a predictor of survival after cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Cancer 92 (7): 1905-12, 2001.

- Wallace S, Ewer MS, Price KJ, et al.: Outcome and cost implications of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the medical intensive care unit of a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer 10 (5): 425-9, 2002.

- Fu S, Hong DS, Naing A, et al.: Outcome analyses after the first admission to an intensive care unit in patients with advanced cancer referred to a phase I clinical trials program. J Clin Oncol 29 (26): 3547-52, 2011.

- Azoulay E, Mokart D, Pène F, et al.: Outcomes of critically ill patients with hematologic malignancies: prospective multicenter data from France and Belgium--a groupe de recherche respiratoire en réanimation onco-hématologique study. J Clin Oncol 31 (22): 2810-8, 2013.

Factors That Influence End-of-Life Care Decisions and Outcomes

Overview

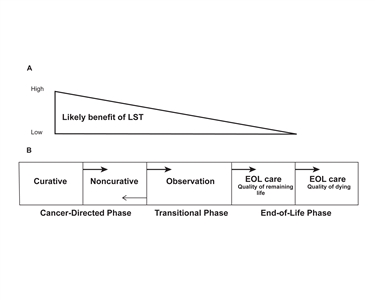

One interpretation of the evidence, summarized in the

This section provides the oncology clinician with insights about potentially influential factors that may lead to more effective interactions with the patient in planning the transition to EOL care. Several notes of caution about the cited studies, however, are highlighted in the following:

- The cross-sectional design of most studies prevents conclusions about causality. For example, studies that demonstrate a correlation between a patient's optimistic predictions of prognosis and treatment decisions may be confounded by the tendency for the patient who chooses a specific treatment to be optimistic about the outcome, rather than the patient's optimism being the primary reason for treatment.

- Definitions of advanced cancer, median survival times of enrolled subjects, and study methodologies may all be relevantly different across studies, and uncontrolled or unrecognized confounders may skew reported correlations.

- Many of the potentially relevant factors were treated as primary or secondary outcomes or as only one variable in multivariate analysis. Thus, the relationships among patient-oncologist communication, health care decision making near the EOL, and outcomes are not always firmly established. Nonetheless, the evidence from multiple sources demonstrates plausible and compelling links.

- Factors unrelated to communication or decision making may influence the health care decisions of patients with advanced cancer near the EOL.

Cited Studies

Three very large, comprehensive studies provide information for characterizing the relationships among markers of quality communication, decision making, health care decisions, and outcomes in patients with advanced cancer. These studies are described here, and results are integrated into subsequent sections.

- The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT): This multisite (Ohio, North Carolina, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, and California) two-phase study evaluated an intervention to improve physician understanding of patient preferences, documentation and timing of do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders, pain, time in intensive care, being comatose or receiving mechanical ventilation before death, and the use of hospital resources.[

1 ] The first phase was a prospective descriptive study to confirm barriers and gaps in patient-physician communication; the second phase was a cluster randomized trial to test an intervention that targeted the identified barriers. A total of 4,301 patients were enrolled in phase I, and 4,804 were enrolled in phase II. The intervention focused on providing reliable information about prognosis, documenting patient and family preferences, and using a skilled nurse to educate patients and families and facilitate communication.Phase I of SUPPORT confirmed significant shortcomings in patient-physician communication.[

2 ,3 ] Phase II demonstrated that the nurse-led intervention did not increase discussions about CPR preferences or concordance between patients and physicians about patients' CPR preferences. It also did not decrease the number of days spent in the intensive care unit (ICU), frequency of mechanical ventilation, or level of pain. - The Coping With Cancer (CwC) study: This prospective, longitudinal, multisite study of terminally ill cancer patients and their informal caregivers examined how psychosocial factors influence patient care and caregiver bereavement.[

4 ] CwC enrolled 718 patients and their caregivers between September 2002 and August 2008. Key eligibility criteria included a diagnosis of advanced cancer (distant metastases and disease refractory to first-line chemotherapy) and presence of an informal caregiver. The median overall survival of enrolled patients was 4.5 months. - The Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) Consortium: This study enrolled more than 5,000 people diagnosed with lung or colorectal cancer between 2003 and 2005 who were identified within weeks of their diagnoses by a rapid-ascertainment method.[

5 ,6 ] Patients lived in one of five geographic areas (Northern California; Los Angeles County, California; North Carolina; Iowa; or Alabama) or received care through a designated health maintenance organization or selected Veterans Health Administration hospital. Patients (or surrogates, if patients had died or were unavailable) were interviewed via computer-assisted surveys 4 to 7 months after diagnosis. The medical records of consenting adults were also abstracted.

Patient Demographics

The goal of planning the transition to EOL care in a deliberate and thoughtful manner is to increase the likelihood that a person with advanced cancer will receive high-quality EOL care consistent with their informed preferences. A variety of patient characteristics influence the interaction with the oncology clinician and the patient's decisions or outcomes. The following section highlights representative results of studies of patient demographics and other factors.

Age

Cancer is a disease of older adults.[

- SUPPORT demonstrated a correlation between increasing age and a decreased desire for life-prolonging treatment. Older patients were less likely to receive aggressive treatments.[

1 ] - Seventy-three patients aged 70 to 89 years with metastatic colon cancer were interviewed about treatment decision making. Fewer than half (44%) of the patients wanted information about expected survival when they made decisions about treatment.[

8 ] - Older women are more likely than younger women to receive palliative care near the EOL. One study reported that 69.6% of women who died of metastatic breast cancer between 1992 and 1998 in the province of Quebec, Canada, did so in an acute-care hospital.[

9 ] While most women (75%) had some indicators of a palliative care–oriented model (as extracted from information contained in two administrative databases), women younger than 50 years were less likely to receive palliative care than were women older than 70 years (odds ratio [OR], 1.85). - One study analyzed the relationships among age, treatment preferences, and treatment received in a cohort of 396 deceased patients who were enrolled in CwC.[

10 ] Patients older than 65 years and patients aged 45 to 64 years were less likely than younger patients to prefer and receive life-prolonging treatments. However, older patients who preferred life-prolonging therapies were less likely than younger patients to receive such treatments.

Gender

- In one study,[

8 ] older men with metastatic colorectal cancer were more likely than women to desire prognostic information (56% vs. 29%; P < .05) - Another study interviewed patients with advanced cancer before and after a visit with an oncology clinician to discuss scan results. Women were more likely than men to recognize the cancer as incurable and to accurately identify the stage of the cancer. Women were also more likely to report that discussions about life expectancy occurred.[

11 ]

Race

- A secondary analysis of CwC demonstrated that Black patients were more likely than White patients to receive intensive treatments near the EOL. The frequency of high-intensity treatments near the EOL did not correlate with stated preferences and, unlike the case with White patients, EOL discussions did not decrease the likelihood of intensive treatments.[

12 ] This effect of race persisted even if a DNR order was in place at the time of death.[13 ] - Another study analyzed interviews with terminally ill White and African American patients to determine whether the patient-reported quality of relationships with physicians correlated with advance care planning (ACP) and preferences for life-sustaining treatment (LST).[

14 ] African American patients reported lower-quality relationships, but these lower ratings did not explain the lower rates of ACP or higher rates of preferences for LST. - Patients of African American or Asian descent are less likely to enroll in hospice and more likely to receive aggressive treatments, including hospitalizations and ICU admissions, than are White patients.[

15 ,16 ,17 ]

Socioeconomic status

- Patients with Medicaid are less likely to receive hospice care than patients insured through Medicare. They are also more likely to be discharged to and die in acute-care facilities than at home with hospice.[

18 ][Level of evidence: II];[19 ] Conversely, in a Medicaid population, Black patients are more likely than White patients to show evidence of EOL discussions.[20 ] - Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in a managed care program were more likely to enroll in hospice and to enroll for longer periods of time.[

21 ]

Patient Understanding of Prognosis

Multiple studies have demonstrated correlations between patients' understanding of their prognoses and health care decisions, medical outcomes, or psychological adjustment near the EOL. However, differences in study methodology, patient populations, measures of prognostic understanding, and the end point studied as the primary outcome preclude definitive conclusions about the relevance of the correlations. Furthermore, causality can only be inferred, given the cross-sectional nature of most studies. Nonetheless, a summary of the published data organized by the measure of prognostic understanding may provide insight into the decision-making processes of patients with advanced cancer.

- Patients often provide overly optimistic estimates of the likelihood of survival beyond 6 months. One group of researchers analyzed the prognostic understanding (measured as an estimate of surviving beyond 6 months) of 917 adults with metastatic colorectal or lung cancer who were enrolled in SUPPORT.[

3 ] Patients who estimated a 90% or higher chance of surviving 6 months were more likely to prefer life-extending therapy and were more likely to experience a readmission, attempted cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or death while on a mechanical ventilator. - A secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial of palliative care interventions for 350 patients with metastatic, incurable lung cancer or noncolorectal gastrointestinal cancer looked at EOL outcomes and patient perception of prognosis. Patients were enrolled within 8 weeks of initial diagnosis and were asked at baseline and at weeks 12 and 24 after enrollment to report their self-perceived health status and to what extent they perceived their cancer as curable. The analysis found that 59% of the patients reported that their health status was "terminally ill" at the assessment falling closest to death, compared with 58% at baseline (59% remained or became accurate, while 41% remained or became inaccurate). A total of 66% of participants reported that their cancer was "likely curable" at the assessment that fell closest to death, compared with 71% at week 12 (35% remained or became accurate, and 65% remained or became inaccurate). The patients who classified their cancer as likely curable were less likely to enroll in hospice (OR, 0.25; P = .002) or die at home (OR, 0.56; P = .043), and they were more likely to be hospitalized in the last 30 days of life (OR, 2.28; P = .011).[

22 ][Level of evidence: II] - Patients frequently fail to correctly report the goal of anticancer treatment. One group of researchers reported that at baseline, 30.4% of a cohort of 181 patients with advanced cancer believed the treatment was curative; 20% reported they did not know.[

23 ] Subjects who were not married, lived in rural areas, died within 6 months, or were receiving chemotherapy were more likely to report the goal of treatment as curative. At a 12-week assessment, fewer patients reported cure as a goal, but the difference was not significant. Another study found that providing patients who were starting second-line chemotherapy with specially designed written and audiovisual information discussing the palliative intention of their treatment did not improve patients' accurate understanding of the goal of treatment.[24 ] - Patients are often unaware of the terminal nature of the diagnosis of advanced cancer. However, patients who are aware of their terminal diagnosis have a higher quality of life (QOL) [

25 ] and are more likely to receive care consistent with their preferences.[26 ,27 ]

Patient Preferences

Respect for patient preferences is essential to high-quality cancer care and to protecting patient autonomy. Patients with advanced cancer who had an opportunity to discuss their EOL preferences were more likely to receive care consistent with their wishes.[

As it stands, evidence suggests that oncology clinicians often do not elicit or clarify patient preferences and, ultimately, fail to provide care consistent with their preferences. For example, a 2011 study [

- 88.2% wanted to be informed about life expectancy (52.7% said they were informed).

- 63.5% wanted to be informed about palliative care (25% said they were informed).

- 56.8% wanted to be informed about EOL decisions (31% said they were informed).

- None of the patients recalled being asked about their information preferences.

The final observation highlights the fundamental question of how oncology clinicians should elicit patient preferences. While direct questioning may seem to be the most straightforward approach, a study of two single-item preference measures demonstrated that the decision-making preferences of patients appear to differ on the basis of what measure was utilized.[

Although the optimal way to elicit patient preferences is uncertain, a few studies have shed light on this topic. Patients with advanced cancer have several preferences of potential significance to planning the transition to EOL care, including:

- Timing and manner of prognostic information disclosure.

- Decision-making role.

- Palliative chemotherapy rather than palliative care without chemotherapy.

- QOL or length of life.

A discussion about preferences is complicated. Preferences may be narrowly construed or may reflect the fundamental values of an individual. In a study of 337 older patients' attitudes about using advance directives to manage EOL care,[

In a 2020 survey study at Johns Hopkins Hospital, investigators interviewed 200 surgical and medical oncology inpatients about their preferences for discussions about advance directives, which their survey defined as "a document or paper that tells your care providers about the kind of medical treatment you would want if you were very sick and could not make those decisions for yourself."[

- 43.5% of patients preferred to have advance care planning discussions with their primary care providers, compared with 7% with their surgeons and 5.5% with their medical oncologists. Patients cited their longitudinal relationships with their primary care providers and these providers' "strong interpersonal skills" as explanations for this preference.

- Patients generally preferred such discussions to occur early in the disease course. A total of 48.5% said they felt the optimal timing was before a cancer diagnosis, and 32% said it was at the time of diagnosis.

- 82.5% of patients thought discussions about advance directives should be initiated by the physician rather than the patient.

Preference for information about prognosis

Patients with life-limiting illnesses desire information about prognosis,[

Preference for decision-making role

A variety of measures assess patients' preferences for a decision-making role. The Control Preference Scale [

- Patients aged 70 to 89 years with metastatic colorectal cancer were interviewed about their preferred role in decision making.[

8 ] Fifty-two percent preferred a passive role. Preference for a passive role was more common among patients who were older or female or had a poorer performance status or newly diagnosed metastatic disease. - In a separate study, a similar proportion (47%) of women aged 31 to 83 years with metastatic breast cancer reported taking a passive role in decision making about palliative chemotherapy. Women who were facing a decision about second-line chemotherapy reported a slightly higher rate of active participation (43% vs. 33%; P = .06).[

36 ] - In another study, 63% of patients with advanced cancer in a palliative care clinic preferred an active role in decision making.[

37 ]

Preference for palliative chemotherapy

Several studies have demonstrated that most patients prefer chemotherapy before consultation with a medical oncologist.[

The preference for chemotherapy may relate in part to the observations that patients are not fully informed, or they reject the information or reinterpret it to fit their perspectives. In addition, patients may value survival more and QOL less than oncology clinicians anticipate.[

Preference for QOL or length of life

As discussed in the

- Multivariate analysis of one study [

43 ] demonstrated that advanced cancer patients' preferences for chemotherapy were explained by higher values assigned to length of life and lower values for QOL. The last variable was measured by the Quality-Quantity Questionnaire (QQQ), which categorizes patients as favoring QOL or length of life or having no preference.[44 ] The patients' preconsultation preferences were most strongly explained by striving for length of life rather than QOL. Given the lack of demonstrable survival benefit of chemotherapy in advanced cancer, the authors speculated that patients may not receive accurate information in the consultation that clearly delineates the goal of chemotherapy. - Another study [

45 ] interviewed 125 outpatients with cancer (all stages) about their attitudes toward treatment. Patients also completed the QQQ. The investigators found that patients who were older, tired, or more negative valued QOL more than others. Patients who were within 6 months of diagnosis rated length of life as more important. It should be noted, however, that patients did not rank the importance of length relative to quality in this study. There was a correlation between striving for QOL and appreciation for ACP. - A third study enrolled only patients with advanced cancer (459 respondents) and asked them to rate the relative value of QOL or length of life.[

46 ] Fifty-five percent valued QOL and length of life equally; 27% preferred QOL; and 18% preferred length of life. A preference for QOL correlated with older age, male gender, and increased levels of education. Patients with a preference for length of life also preferred less pessimistic communication from oncologists.

Patient Goals of Care

Discussions about goals of care with advanced-cancer patients are considered to be a critical component of planning the transition to EOL care. However, the definitions of goals of care vary significantly in the relevant literature. Before discussing observations related to goals of care with patients with advanced cancer (and other life-limiting illnesses), it is important to consider whether to distinguish goals of treatment from goals of care.

- Some investigators have used the phrase goals of care to identify the goals of disease-directed treatments. Perhaps it would be clearer if such goals were labeled goals of treatment.

- Viewed another way, goals of care are distinct from goals related to treatment of disease with remittive or curative intent; these goals reflect the interests of patients and families after they have accepted that disease-directed treatments will not accomplish their intended goals, and they seek "the profound human needs for meaning, comfort, and direction."[

47 ] From that perspective, goals of care are similar to the attributes that define agood death , as discussed earlier.

Another perspective is that there is a continuum of goals and that the purpose of conversations about goals of care is to help patients identify alternatives for achieving their goals. A structured literature review and a qualitative analysis of palliative care consultations about goals of care support this perspective, as summarized below:

- One study analyzed relevant publications to establish a categorization of goals of care for patients with life-limiting illnesses.[

47 ] The authors proposed six comprehensive goals: be cured; live longer; improve or maintain function, QOL, and independence; be comfortable; achieve life goals; and provide support for family or caregiver. - Another study reported a qualitative analysis of prognostic communication in palliative care consultations.[

48 ] The investigators noted that palliative care physicians used a tactic of excluding certain goals of care to encourage patients to think about alternative goals. This tactic suggests that treatment-related goals are often replaced by more personal goals once disease-directed treatment is not advisable.

At present, there are no data on the positive or negative influence of discussions about goals of care on EOL outcomes of patients with advanced cancer.

Religious and Spiritual Beliefs and Values of Patients

Patient religiosity and the provision of spiritual care consistent with a patient's preference have been correlated with EOL outcomes. A series of reports from CwC [

In analyses adjusted for demographic differences, higher levels of positive religious coping were significantly related to the receipt of mechanical ventilation, compared with low levels of religious coping (11.3% vs. 3.6%) and intensive life-prolonging care during the last week of life (13.6% vs. 4.2%).[

Patient-Oncologist EOL Discussions

Recall of EOL discussions

Recall of EOL discussions influences the EOL health care decisions and outcomes of patients with advanced cancer. A total of 123 of 332 patients (37%) enrolled in CwC answered affirmatively when asked, "Have you and your doctors discussed any particular wishes you have about the care you would want to receive if you were dying?"[

A subsequent analysis reported on the treatment preferences of 325 patients who died while enrolled in CwC.[

The Nature of the Decision

Decision to receive cancer-directed therapy

Patients with advanced cancer frequently receive multiple regimens of chemotherapy over the course of their treatment. Whether the decision involves first-line or second-line treatment for advanced disease may influence the decision-making process. One group of investigators conducted 117 semistructured interviews of 102 women with advanced breast cancer who were receiving first-line (n = 70) or second-line (n = 47) palliative chemotherapy.[

Decision to limit treatment

Most deaths resulting from advanced cancer are preceded by decisions to limit treatment. Given the prevalence, importance, and challenges of these decisions, however, there is relatively little information about how patient preferences are considered during decision making.

Using researchers embedded in health care teams, one group of investigators characterized the deliberations about limiting potentially life-prolonging treatments for 76 hospitalized patients with incurable cancer.[

References:

- A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA 274 (20): 1591-8, 1995 Nov 22-29.

- Haidet P, Hamel MB, Davis RB, et al.: Outcomes, preferences for resuscitation, and physician-patient communication among patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Am J Med 105 (3): 222-9, 1998.

- Weeks JC, Cook EF, O'Day SJ, et al.: Relationship between cancer patients' predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA 279 (21): 1709-14, 1998.

- Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al.: Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 300 (14): 1665-73, 2008.

- Chen AB, Cronin A, Weeks JC, et al.: Palliative radiation therapy practice in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: a Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS) Study. J Clin Oncol 31 (5): 558-64, 2013.

- Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Fletcher RH, et al.: Understanding cancer treatment and outcomes: the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol 22 (15): 2992-6, 2004.

- American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures 2025. American Cancer Society, 2025.

Available online . Last accessed January 16, 2025. - Elkin EB, Kim SH, Casper ES, et al.: Desire for information and involvement in treatment decisions: elderly cancer patients' preferences and their physicians' perceptions. J Clin Oncol 25 (33): 5275-80, 2007.

- Gagnon B, Mayo NE, Hanley J, et al.: Pattern of care at the end of life: does age make a difference in what happens to women with breast cancer? J Clin Oncol 22 (17): 3458-65, 2004.

- Parr JD, Zhang B, Nilsson ME, et al.: The influence of age on the likelihood of receiving end-of-life care consistent with patient treatment preferences. J Palliat Med 13 (6): 719-26, 2010.

- Fletcher K, Prigerson HG, Paulk E, et al.: Gender differences in the evolution of illness understanding among patients with advanced cancer. J Support Oncol 11 (3): 126-32, 2013.

- Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Paulk E, et al.: Racial differences in predictors of intensive end-of-life care in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 27 (33): 5559-64, 2009.

- Mack JW, Paulk ME, Viswanath K, et al.: Racial disparities in the outcomes of communication on medical care received near death. Arch Intern Med 170 (17): 1533-40, 2010.

- Smith AK, Davis RB, Krakauer EL: Differences in the quality of the patient-physician relationship among terminally ill African-American and white patients: impact on advance care planning and treatment preferences. J Gen Intern Med 22 (11): 1579-82, 2007.

- Smith AK, Earle CC, McCarthy EP: Racial and ethnic differences in end-of-life care in fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries with advanced cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc 57 (1): 153-8, 2009.

- Haas JS, Earle CC, Orav JE, et al.: Lower use of hospice by cancer patients who live in minority versus white areas. J Gen Intern Med 22 (3): 396-9, 2007.

- Mullins MA, Ruterbusch JJ, Clarke P, et al.: Trends and racial disparities in aggressive end-of-life care for a national sample of women with ovarian cancer. Cancer 127 (13): 2229-2237, 2021.

- Singh S, Molina E, Perraillon M, et al.: Post-Acute Care Outcomes of Cancer Patients <65 Reveal Disparities in Care Near the End of Life. J Palliat Med 26 (8): 1081-1089, 2023.

- Mack JW, Chen K, Boscoe FP, et al.: Underuse of hospice care by Medicaid-insured patients with stage IV lung cancer in New York and California. J Clin Oncol 31 (20): 2569-79, 2013.

- Sharma RK, Dy SM: Documentation of information and care planning for patients with advanced cancer: associations with patient characteristics and utilization of hospital care. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 28 (8): 543-9, 2011.

- McCarthy EP, Burns RB, Ngo-Metzger Q, et al.: Hospice use among Medicare managed care and fee-for-service patients dying with cancer. JAMA 289 (17): 2238-45, 2003.

- Gray TF, Plotke R, Heuer L, et al.: Perceptions of prognosis and end-of-life care outcomes in patients with advanced lung and gastrointestinal cancer. Palliat Med 37 (5): 740-748, 2023.

- Craft PS, Burns CM, Smith WT, et al.: Knowledge of treatment intent among patients with advanced cancer: a longitudinal study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 14 (5): 417-25, 2005.

- Enzinger AC, Uno H, McCleary N, et al.: Effectiveness of a Multimedia Educational Intervention to Improve Understanding of the Risks and Benefits of Palliative Chemotherapy in Patients With Advanced Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol 6 (8): 1265-1270, 2020.

- Yun YH, Kwon YC, Lee MK, et al.: Experiences and attitudes of patients with terminal cancer and their family caregivers toward the disclosure of terminal illness. J Clin Oncol 28 (11): 1950-7, 2010.

- Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, et al.: End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol 28 (7): 1203-8, 2010.

- Loh KP, Seplaki CL, Sanapala C, et al.: Association of Prognostic Understanding With Health Care Use Among Older Adults With Advanced Cancer: A Secondary Analysis of a Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open 5 (2): e220018, 2022.

- Pardon K, Deschepper R, Vander Stichele R, et al.: Are patients' preferences for information and participation in medical decision-making being met? Interview study with lung cancer patients. Palliat Med 25 (1): 62-70, 2011.

- Gattellari M, Ward JE: Measuring men's preferences for involvement in medical care: getting the question right. J Eval Clin Pract 11 (3): 237-46, 2005.

- Hawkins NA, Ditto PH, Danks JH, et al.: Micromanaging death: process preferences, values, and goals in end-of-life medical decision making. Gerontologist 45 (1): 107-17, 2005.

- Kubi B, Istl AC, Lee KT, et al.: Advance Care Planning in Cancer: Patient Preferences for Personnel and Timing. JCO Oncol Pract 16 (9): e875-e883, 2020.

- Fried TR, Bradley EH, O'Leary J: Prognosis communication in serious illness: perceptions of older patients, caregivers, and clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc 51 (10): 1398-403, 2003.

- Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, et al.: Communicating with realism and hope: incurable cancer patients' views on the disclosure of prognosis. J Clin Oncol 23 (6): 1278-88, 2005.

- Hagerty RG, Butow PN, Ellis PM, et al.: Communicating prognosis in cancer care: a systematic review of the literature. Ann Oncol 16 (7): 1005-53, 2005.

- Degner LF, Sloan JA: Decision making during serious illness: what role do patients really want to play? J Clin Epidemiol 45 (9): 941-50, 1992.

- Grunfeld EA, Maher EJ, Browne S, et al.: Advanced breast cancer patients' perceptions of decision making for palliative chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 24 (7): 1090-8, 2006.

- Bruera E, Sweeney C, Calder K, et al.: Patient preferences versus physician perceptions of treatment decisions in cancer care. J Clin Oncol 19 (11): 2883-5, 2001.

- Kiely BE, Stockler MR, Tattersall MH: Thinking and talking about life expectancy in incurable cancer. Semin Oncol 38 (3): 380-5, 2011.

- Koedoot CG, de Haan RJ, Stiggelbout AM, et al.: Palliative chemotherapy or best supportive care? A prospective study explaining patients' treatment preference and choice. Br J Cancer 89 (12): 2219-26, 2003.

- Harrington SE, Smith TJ: The role of chemotherapy at the end of life: "when is enough, enough?". JAMA 299 (22): 2667-78, 2008.

- Epstein RM, Peters E: Beyond information: exploring patients' preferences. JAMA 302 (2): 195-7, 2009.

- Blinman P, King M, Norman R, et al.: Preferences for cancer treatments: an overview of methods and applications in oncology. Ann Oncol 23 (5): 1104-10, 2012.

- Koedoot CG, Oort FJ, de Haan RJ, et al.: The content and amount of information given by medical oncologists when telling patients with advanced cancer what their treatment options are. palliative chemotherapy and watchful-waiting. Eur J Cancer 40 (2): 225-35, 2004.

- Stiggelbout AM, de Haes JC, Kiebert GM, et al.: Tradeoffs between quality and quantity of life: development of the QQ Questionnaire for Cancer Patient Attitudes. Med Decis Making 16 (2): 184-92, 1996 Apr-Jun.

- Voogt E, van der Heide A, Rietjens JA, et al.: Attitudes of patients with incurable cancer toward medical treatment in the last phase of life. J Clin Oncol 23 (9): 2012-9, 2005.

- Meropol NJ, Egleston BL, Buzaglo JS, et al.: Cancer patient preferences for quality and length of life. Cancer 113 (12): 3459-66, 2008.

- Kaldjian LC, Curtis AE, Shinkunas LA, et al.: Goals of care toward the end of life: a structured literature review. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 25 (6): 501-11, 2008 Dec-2009 Jan.

- Norton SA, Metzger M, DeLuca J, et al.: Palliative care communication: linking patients' prognoses, values, and goals of care. Res Nurs Health 36 (6): 582-90, 2013.

- Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, et al.: Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA 301 (11): 1140-7, 2009.

- Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al.: Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol 28 (3): 445-52, 2010.

- Maciejewski PK, Phelps AC, Kacel EL, et al.: Religious coping and behavioral disengagement: opposing influences on advance care planning and receipt of intensive care near death. Psychooncology 21 (7): 714-23, 2012.

- Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, et al.: Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. J Sci Study Relig 37 (4): 710-24, 1998.

- Keating NL, Beth Landrum M, Arora NK, et al.: Cancer patients' roles in treatment decisions: do characteristics of the decision influence roles? J Clin Oncol 28 (28): 4364-70, 2010.

- Winkler EC, Reiter-Theil S, Lange-Riess D, et al.: Patient involvement in decisions to limit treatment: the crucial role of agreement between physician and patient. J Clin Oncol 27 (13): 2225-30, 2009.

Potential Barriers to Planning the Transition to End-of-Life Care

The preferences of patients with advanced cancer should, in large part, determine the care they receive. However, evidence suggests that patients lack sufficient opportunity to develop informed preferences and, as a result, may seek care that is potentially inconsistent with their personal values and goals. For more information, see the

This section identifies potential barriers that may prevent a patient with advanced cancer and his or her oncologist from discussing prognosis, goals, options, and preferences.[

Potential barriers include the following:

- Patients' interpretations of prognostic information.

- Lack of agreement between patients and oncologists.

- Oncologists' communication behaviors.

- Oncologists' misconceptions about the harm of end-of-life (EOL) discussions.

- Oncologists' attitudes and preferences.

- Reimbursement for chemotherapy and practice economics.

- Uncertainty about options other than disease-directed treatments.

Patients' Interpretations of Prognostic Information

A consistent finding over the last two decades is that patients with advanced cancer are typically overly optimistic about their life expectancies or the potential for cure with cancer-directed therapies.

- In a study of 1,193 patients in the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) Consortium, a significant majority of patients with advanced lung or colorectal cancer did not understand that treatment was not curative. Sixty-nine percent of patients did not understand that chemotherapy was unlikely to cure their cancers.[

2 ] Patients who were not White, were diagnosed with colorectal cancer, or reported satisfaction with physician communication were more likely to report inaccurate understanding of treatment intent. - Similarly, 64% of patients with incurable lung cancer who received radiation therapy did not understand that it was not likely to cure their cancers. Older and non-White patients were more likely to misunderstand; surrogates of patients were more likely to understand.[

3 ]

There are many potential barriers to a more accurate understanding of prognosis, including poor communication by oncology clinicians. However, patients also interpret information for reasons unrelated to the quality of communication. The perspectives of patients with advanced cancer who enroll in phase I clinical trials or surrogate decision makers for patients in intensive care units (ICUs) provide some insights into why advanced cancer patients might misinterpret prognostic information.

- Patients' optimistic expectations of benefit from phase I trials were associated with a better quality of life, stronger religious faith, optimism, poorer numeracy (ability to understand a statistical estimate of treatment outcome), and monetary risk seeking. They were unrelated to age, gender, educational level, or functional status.[

4 ] - In a study of 163 patients enrolled in a phase I trial, most were aware of hospice (81%) or palliative care (84%), but few considered either choice seriously (hospice, 10%; palliative care, 7%). Seventy-five percent of patients reported the most important influence was awareness that their cancer was growing; 63% of them stated the knowledge that the phase I drug killed cancer cells was the most important factor in their decision to enroll.[

5 ] - In a study of 80 surrogate decision makers recruited from the families of ICU patients, most were fairly accurate in their interpretations of quantitative information and less ambiguous qualitative estimates by ICU physicians. However, several potentially relevant sources of prognostic misunderstanding included the need to express optimism, the belief that the patients' fortitude would lead to better-than-predicted outcomes, and a disbelief that physicians can predict accurately.[

6 ]

Lack of Agreement Between Patients and Oncologists

Multiple conversations between patients with advanced cancer and their oncologists should lead to an understanding about prognoses, goals, preferences, options, and the decision-making process. However, evidence suggests that patients and oncologists frequently do not reach the same conclusions about these issues. How this lack of agreement affects the transition to EOL care is not certain. However, disagreement with or misperceptions about goals of treatment, for example, are unlikely to contribute positively to the timely planning for the transition to EOL care.

Understanding of prognosis

One group of investigators analyzed the prognostic estimates of 917 adults with metastatic colorectal or lung cancer who were enrolled in the Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT) and their physicians.[

- Patients were more optimistic than physicians.

- Physician estimates were more calibrated with the observed survival than were patient estimates.

- Patients who were more optimistic than their oncologists were more likely to prefer life-extending treatments.

The poor concordance between patients and oncology clinicians has been observed in a diverse range of patients, including patients with acute myeloid leukemia [

Discordance about life expectancy between patients with advanced cancer and their oncologists may be explained by poor communication or factors independent of oncologists' prognostic estimates. One group of researchers attempted to clarify the source of prognostic discordance by surveying 236 patients with advanced cancer who participated in a randomized clinical trial of a communication intervention.[

As expected, most patient-oncologist dyads were discordant (161 of 236 ratings [68%]; 95% confidence interval [CI], 62%–75%). Almost all discordant patients expressed a more-optimistic prognosis than their oncologists (155 of 161 patients [96%]).[

Goals of treatment

Patients and oncologists frequently do not share an understanding of the goals of cancer treatment. One group of researchers reported that in 25% of the advanced-cancer patient–physician dyads surveyed, the patient thought the goal of care was to cure disease when it was not.[

A study of 206 cancer patients and their 11 oncologists sought to identify how well the oncologists understood their patients' goals of care, defined as preference for quality of life versus preference for length of life.[

Topics recalled from consultation

Researchers reported that patients and oncologists frequently recalled different components of communication and decision making from discussions of phase I trials.[

Patient preference for decision-making role

Oncology clinicians frequently do not correctly identify patient preferences for decision-making roles. Results from a few Illustrative studies are summarized below.

- In a study of older patients with metastatic colorectal cancer, 52% preferred a passive role. However, oncologists correctly identified patient preferences only 41% of the time.[

14 ] - Palliative care physicians correctly identified the decision-making preference of patients with advanced cancer in a palliative care clinic only 38% of the time.[

15 ]

Assessment of patient performance status

Physicians evaluate patient performance status (PS) in determining prognosis and in making treatment decisions. Investigators compared the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group PS reported by physicians and 1,636 patients who had advanced lung or colorectal cancers.[

Patient preference for cardiopulmonary resuscitation

The initial phase of SUPPORT demonstrated that only 47% of physicians knew when their patients wanted to avoid cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).[

Oncologist Communication Behaviors

This section summarizes the evidence that identifies deficits in the communication behaviors of oncologists treating patients who have advanced cancer. This evidence strongly suggests that doctor-patient communication frequently does not fully support informed or shared decision making. This information will allow oncology clinicians to reflect on their communication habits and consider modifying impediments to the timely planning for the transition to EOL care.

Observational studies of patient-oncologist communication

Investigators reported a study of audiotaped consultations between one of nine oncologists and each of 118 patients with advanced cancer.[

- Most oncologists disclosed the noncurative intent of chemotherapy in advanced cancer, but few discussed alternatives to chemotherapy. In 74.6% of encounters, patients were told the cancer was incurable. However, patients were presented with information about life expectancy in only 57.6% of encounters and were given information about treatment alternatives in only 44.6% of encounters.

- Oncologists rarely checked patient understanding, asking about patient understanding of the disclosed information and decision-making process in only 10% of encounters.

- Essential elements of shared decision making were frequently missing. The participating oncologists frequently acknowledged the uncertainty of treatment benefit (72.9%), discussed trade-offs in receiving treatment (60.2%), and elicited patient perspectives about treatment (69.5%). However, only 29.7% of patients were offered a choice, and in only 10.2% of the encounters did the oncologist assess the patient's comprehension.

Additional deficits in oncologist communication behaviors include the following:

- Oncologists frequently use ambiguous or falsely reassuring language, such as inappropriately optimistic statements. One group of researchers analyzed audiotapes of encounters between oncologists and patients in which the oncologists had provided a likelihood of cure using current treatments.[

21 ] The audiotapes were selected according to the degree of prognostic agreement and then coded to determine factors that predict agreement. Oncologists were more likely to make optimistic statements, but pessimistic statements were more likely to increase the degree of prognostic agreement. The authors concluded that the best communication strategy may include acknowledging that the tendency to be optimistic may interfere with patient understanding of prognosis and striving to provide honest information as warranted by the prognosis. - Oncologists frequently do not discuss the anticipated survival benefit of chemotherapy in advanced cancer. One group of investigators demonstrated that in 26 of 37 analyzed consultations, the oncologist did not provide the patient with information about the potential survival gain of palliative (i.e., noncurative) chemotherapy.[

22 ]

Oncologist self-reported practices in prognostic communication

There is evidence that physicians' attitudes toward prognostic communication influence patients' prognostic awareness. In an analysis of physician surveys from the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) Consortium,[

Another study reported that 65% of physicians surveyed discussed prognosis immediately with asymptomatic patients who had advanced cancer and anticipated life expectancies of 4 to 6 months.[

Oncologists' Misconceptions About the Harm of EOL Discussions

Oncologists cite several reasons for their reluctance to engage in EOL discussions. However, several studies have provided evidence that many of the concerns—e.g., causing psychological harm or destroying hope—are not valid.[

- A multisite, prospective, longitudinal cohort study reported that discussions about EOL care were not psychologically harmful. Patients with advanced cancer who answered affirmatively to the question, "Have you and your doctors discussed any particular wishes you have about the care you would want to receive if you were dying?" did not have a higher rate of generalized anxiety disorder or major depressive disorder than did patients who did not recall such discussions (3.3% vs. 1.4% and 8.3% vs. 5.8%, respectively).[

27 ] In addition, recall of such discussions was not related to levels of worry. - Another study found that patient anxiety caused by disclosure of information and decision making was transient or may have improved psychological adjustment. The amount of information disclosed by oncologists did not predict levels of patient anxiety.[

20 ] However, greater encouragement of the patient to participate in decision making was independently associated with higher anxiety levels immediately after the consultation and 2 weeks later.In another study, men with advanced cancer who estimated a lower likelihood of survival at 6 months had increased levels of anxiety and depression.[

28 ] However, men who reported having a full discussion about prognosis with their oncologist had less depression and similar levels of anxiety. Thus, discussions about prognosis moderated the relationships with anxiety and depression and may have facilitated long-term psychological adjustment. - A study found that explicit disclosure about prognosis and reassurance about nonabandonment were helpful to patients. Researchers studied how patients with breast cancer and healthy women reacted to two levels of prognostic disclosure and reassurance portrayed in four different video vignettes.[

29 ] Explicitness and reassurance decreased uncertainty and anxiety. The authors cautioned that the nature of the findings is experimental.

Oncologist Attitudes and Preferences

Studies strongly suggest that oncologists' attitudes and preferences influence their communication and decision-making behaviors in a manner that might change patients' EOL decisions.

One study found that hospital staff attributed variations in aggressiveness of care near the EOL to physician characteristics, including physician beliefs, attitudes, and socialization within the practice of medicine.[

Oncologist preferences for noncurative treatments

Oncology clinicians influence patients' understanding of treatment preferences. Dutch researchers surveyed medical oncologists about their preferences for palliative (noncurative) chemotherapy or observation using case vignettes.[

Oncologists and shared decision making

In surveys, oncologists are broadly supportive of the concept of shared decision making. However, empirical research demonstrates that oncologists' communication behaviors frequently do not support shared decision making.

One group of investigators interviewed Australian cancer specialists about their inclusion of patients in decision making and identified several factors that influence patient involvement.[

- Stage of disease.

- Availability of treatment options.

- Risks to the patient.

In addition, public perception of the disease and whether there was a clear best treatment option were relevant. Cancer specialists were more likely to include patients in decision making when the disease stage was advanced and treatment options were less certain. Patient characteristics that decreased doctors' efforts to involve the patient included:

- Increased anxiety.

- Older age.

- Female gender.

- A Mediterranean or Central or Eastern European background.

- A busy professional life.

The doctors were aware of patient preferences for involvement but felt most patients deferred to their expertise. Furthermore, few physicians had a validated approach to determine patient preferences.

Oncologist attitudes toward EOL care

Attitudes toward EOL care may also influence the communication and decision-making behaviors of oncologists. In a qualitative study of 18 academic oncologists who were asked to reflect on recent patient deaths, one group of researchers reported that oncologists who viewed EOL care as an important part of their job reported increased job satisfaction.[

- Feeling that the patient was being deprived of hope.

- Concerns that the family would blame the doctor.

- Concerns that the patient would lose control.

- Concerns that there was inadequate time to discuss the recommendation.

Reimbursement for Chemotherapy and Practice Economics

Before 2003, reimbursement for chemotherapy greatly exceeded acquisition costs for medical oncologists. Although the profit margin for chemotherapy has decreased, the treatment remains a significant source of oncologists' income. Researchers demonstrated that physicians' decisions to prescribe chemotherapy for patients with advanced cancer was not affected by reimbursement rates, but more costly regimens were more likely with higher rates of reimbursement.[

- Urologists who acquired ownership in intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) increased their utilization of IMRT (from 13.1% to 32.3%), compared with urologists who did not own IMRT services (from 14.3% to 15.6%).[

38 ] The rate at National Comprehensive Cancer Network cancer centers was unchanged at 8%. - Oncologists who practice in a fee-for-service setting or those who are paid a salary with productivity incentives are more likely to report that their income increases with higher orders of chemotherapy or growth factors.[

39 ]

Uncertainty About Options Other Than Disease-Directed Treatments

A final barrier to planning the transition to EOL care may be confusing language when patients begin to ponder forgoing resuscitation and other life-prolonging interventions. On the basis of their experiences or understanding, oncology clinicians, patients, and families assign different—and often valid—meanings to terms such as supportive or palliative. A 2013 systematic review of the literature found widespread inconsistencies in the definitions of supportive care, palliative care, and hospice.[

For term definitions and a discussion of clearly communicating the purpose of each level of care for patients with advanced cancer, see the

References:

- Quill TE, Holloway RG: Evidence, preferences, recommendations--finding the right balance in patient care. N Engl J Med 366 (18): 1653-5, 2012.

- Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al.: Patients' expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med 367 (17): 1616-25, 2012.

- Chen AB, Cronin A, Weeks JC, et al.: Expectations about the effectiveness of radiation therapy among patients with incurable lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 31 (21): 2730-5, 2013.

- Weinfurt KP, Castel LD, Li Y, et al.: The correlation between patient characteristics and expectations of benefit from Phase I clinical trials. Cancer 98 (1): 166-75, 2003.

- Agrawal M, Grady C, Fairclough DL, et al.: Patients' decision-making process regarding participation in phase I oncology research. J Clin Oncol 24 (27): 4479-84, 2006.

- Zier LS, Sottile PD, Hong SY, et al.: Surrogate decision makers' interpretation of prognostic information: a mixed-methods study. Ann Intern Med 156 (5): 360-6, 2012.

- Weeks JC, Cook EF, O'Day SJ, et al.: Relationship between cancer patients' predictions of prognosis and their treatment preferences. JAMA 279 (21): 1709-14, 1998.

- Sekeres MA, Stone RM, Zahrieh D, et al.: Decision-making and quality of life in older adults with acute myeloid leukemia or advanced myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia 18 (4): 809-16, 2004.

- Lee SJ, Fairclough D, Antin JH, et al.: Discrepancies between patient and physician estimates for the success of stem cell transplantation. JAMA 285 (8): 1034-8, 2001.

- Gramling R, Fiscella K, Xing G, et al.: Determinants of Patient-Oncologist Prognostic Discordance in Advanced Cancer. JAMA Oncol 2 (11): 1421-1426, 2016.

- Lennes IT, Temel JS, Hoedt C, et al.: Predictors of newly diagnosed cancer patients' understanding of the goals of their care at initiation of chemotherapy. Cancer 119 (3): 691-9, 2013.

- Douglas SL, Daly BJ, Lipson AR, et al.: Association between strong patient-oncologist agreement regarding goals of care and aggressive care at end-of-life for patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer 28 (11): 5139-5146, 2020.

- Jenkins V, Solis-Trapala I, Langridge C, et al.: What oncologists believe they said and what patients believe they heard: an analysis of phase I trial discussions. J Clin Oncol 29 (1): 61-8, 2011.

- Elkin EB, Kim SH, Casper ES, et al.: Desire for information and involvement in treatment decisions: elderly cancer patients' preferences and their physicians' perceptions. J Clin Oncol 25 (33): 5275-80, 2007.

- Bruera E, Sweeney C, Calder K, et al.: Patient preferences versus physician perceptions of treatment decisions in cancer care. J Clin Oncol 19 (11): 2883-5, 2001.

- Schnadig ID, Fromme EK, Loprinzi CL, et al.: Patient-physician disagreement regarding performance status is associated with worse survivorship in patients with advanced cancer. Cancer 113 (8): 2205-14, 2008.

- A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. JAMA 274 (20): 1591-8, 1995 Nov 22-29.

- Haidet P, Hamel MB, Davis RB, et al.: Outcomes, preferences for resuscitation, and physician-patient communication among patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. Am J Med 105 (3): 222-9, 1998.

- Downey L, Au DH, Curtis JR, et al.: Life-sustaining treatment preferences: matches and mismatches between patients' preferences and clinicians' perceptions. J Pain Symptom Manage 46 (1): 9-19, 2013.

- Gattellari M, Voigt KJ, Butow PN, et al.: When the treatment goal is not cure: are cancer patients equipped to make informed decisions? J Clin Oncol 20 (2): 503-13, 2002.

- Robinson TM, Alexander SC, Hays M, et al.: Patient-oncologist communication in advanced cancer: predictors of patient perception of prognosis. Support Care Cancer 16 (9): 1049-57, 2008.

- Audrey S, Abel J, Blazeby JM, et al.: What oncologists tell patients about survival benefits of palliative chemotherapy and implications for informed consent: qualitative study. BMJ 337: a752, 2008.

- Liu PH, Landrum MB, Weeks JC, et al.: Physicians' propensity to discuss prognosis is associated with patients' awareness of prognosis for metastatic cancers. J Palliat Med 17 (6): 673-82, 2014.

- Daugherty CK, Hlubocky FJ: What are terminally ill cancer patients told about their expected deaths? A study of cancer physicians' self-reports of prognosis disclosure. J Clin Oncol 26 (36): 5988-93, 2008.

- Keating NL, Landrum MB, Rogers SO, et al.: Physician factors associated with discussions about end-of-life care. Cancer 116 (4): 998-1006, 2010.

- Cohen MG, Althouse AD, Arnold RM, et al.: Is Advance Care Planning Associated With Decreased Hope in Advanced Cancer? JCO Oncol Pract 17 (2): e248-e256, 2021.

- Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al.: Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 300 (14): 1665-73, 2008.

- Cripe LD, Rawl SM, Schmidt KK, et al.: Discussions of life expectancy moderate relationships between prognosis and anxiety or depression in men with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med 15 (1): 99-105, 2012.

- van Vliet LM, van der Wall E, Plum NM, et al.: Explicit prognostic information and reassurance about nonabandonment when entering palliative breast cancer care: findings from a scripted video-vignette study. J Clin Oncol 31 (26): 3242-9, 2013.

- Larochelle MR, Rodriguez KL, Arnold RM, et al.: Hospital staff attributions of the causes of physician variation in end-of-life treatment intensity. Palliat Med 23 (5): 460-70, 2009.

- Ubel PA, Angott AM, Zikmund-Fisher BJ: Physicians recommend different treatments for patients than they would choose for themselves. Arch Intern Med 171 (7): 630-4, 2011.

- Koedoot CG, De Haes JC, Heisterkamp SH, et al.: Palliative chemotherapy or watchful waiting? A vignettes study among oncologists. J Clin Oncol 20 (17): 3658-64, 2002.

- Kozminski MA, Neumann PJ, Nadler ES, et al.: How long and how well: oncologists' attitudes toward the relative value of life-prolonging v. quality of life-enhancing treatments. Med Decis Making 31 (3): 380-5, 2011 May-Jun.

- Shepherd HL, Butow PN, Tattersall MH: Factors which motivate cancer doctors to involve their patients in reaching treatment decisions. Patient Educ Couns 84 (2): 229-35, 2011.

- Jackson VA, Mack J, Matsuyama R, et al.: A qualitative study of oncologists' approaches to end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 11 (6): 893-906, 2008.

- Otani H, Morita T, Esaki T, et al.: Burden on oncologists when communicating the discontinuation of anticancer treatment. Jpn J Clin Oncol 41 (8): 999-1006, 2011.