Shop for Plans

Shop for your own coverage

Plans through your employer

Learn about the medical, dental, pharmacy, behavioral, and voluntary benefits your employer may offer.

Learn

Living or working abroad?

Von Hippel-Lindau Disease (PDQ®): Genetics - Health Professional Information [NCI]

Introduction

Von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) is an autosomal dominant disease that can predispose individuals to multiple neoplasms. Germline pathogenic variants in the VHLgene predispose individuals to specific types of benign tumors, malignant tumors, and cysts in many organ systems. These tumors and cysts include central nervous system hemangioblastomas; retinal hemangioblastomas; clear cell renal cell carcinomas and renal cysts; pheochromocytomas, cysts, cystadenomas, and neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas; endolymphatic sac tumors; and cystadenomas of the epididymis (males) and of the broad ligament (females).[

References:

- Choyke PL, Glenn GM, Walther MM, et al.: von Hippel-Lindau disease: genetic, clinical, and imaging features. Radiology 194 (3): 629-42, 1995.

- Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, et al.: von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet 361 (9374): 2059-67, 2003.

- Pithukpakorn M, Glenn G: von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Community Oncology 1 (4): 232-43, 2004.

- Glenn GM, Daniel LN, Choyke P, et al.: Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease: distinct phenotypes suggest more than one mutant allele at the VHL locus. Hum Genet 87 (2): 207-10, 1991.

- Wolters WPG, Dreijerink KMA, Giles RH, et al.: Multidisciplinary integrated care pathway for von Hippel-Lindau disease. Cancer 128 (15): 2871-2879, 2022.

- Jonasch E, Song Y, Freimark J, et al.: Epidemiology and Economic Burden of von Hippel-Lindau Disease-Associated Renal Cell Carcinoma in the United States. Clin Genitourin Cancer 21 (2): 238-247, 2023.

Genetics

VHLGene

The VHLgene is a tumor suppressor gene located on the short arm of chromosome 3 at cytoband 3p25-26.[

Prevalence and rare founder effects

The incidence of VHL is estimated to be between 1 case per 27,000 and 1 case per 43,000 live births in the general population.[

Penetrance of pathogenic variants

VHL pathogenic variants are highly penetrant, with manifestations found in nearly 100% of carriers by age 65 years.[

Risk factors for VHL

Each offspring of an individual with VHL has a 50% chance of inheriting the VHL pathogenic variant allele from their affected parent. For more information, see the

Genotype-phenotype correlations

Specific alterations in the VHL gene may help predict an individual's risk of developing renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and other VHL-associated tumors. Classifying genotypes into different risk groups has been a goal to better inform screening for VHL disease manifestations. There have been efforts to subdivide patients based on familial variants. For example, in 1991, researchers classified VHL cases into two different types: type 1 VHL (VHL without pheochromocytomas [PHEOs]) and type 2 VHL (VHL with PHEOs).[

In recent years, there have been exceptions to these VHL classifications, suggesting that screening for all disease manifestations is warranted in all individuals with VHL.[

De novo pathogenic variants and mosaicism

In some cases, an individual can be diagnosed with VHL, even when this disease is not present in other family members. This scenario can occur when an affected individual has a de novo (new) pathogenic variant in the VHL gene. Patients who were diagnosed with VHL and have no family history of VHL comprise about 23% of VHL kindreds.[

Depending on the embryogenesis stage at which the new variant occurs, there may be different somatic cell lineages carrying the variant. This influences the extent of mosaicism seen in the cell lineages. Mosaicism occurs when two or more cell lines in an individual differ by genotype. These differing cell lines all arise from the same zygote.[

Allelic disorder

VHL-associated polycythemia (also known as familial erythrocytosis type 2 or Chuvash polycythemia) is a rare, autosomal recessive blood disorder caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous pathogenic variants in VHL in which affected individuals develop abnormally high numbers of red blood cells (polycythemia). The affected individuals have biallelic pathogenic variants in the VHL gene. It had been originally thought that the typical VHL syndromic tumors do not occur in these affected individuals.[

Other Genetic Alterations

In sporadic RCC, mutational inactivation of the VHL gene is the most frequent molecular event. In addition to VHL inactivation, sporadic clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC) tumors harbor frequent variants in other genes, including PBRM1, SETD2, and BAP1.[

References:

- Latif F, Tory K, Gnarra J, et al.: Identification of the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Science 260 (5112): 1317-20, 1993.

- Knudson AG, Strong LC: Mutation and cancer: neuroblastoma and pheochromocytoma. Am J Hum Genet 24 (5): 514-32, 1972.

- Knudson AG: Genetics of human cancer. Annu Rev Genet 20: 231-51, 1986.

- Maher ER, Iselius L, Yates JR, et al.: Von Hippel-Lindau disease: a genetic study. J Med Genet 28 (7): 443-7, 1991.

- Binderup ML, Galanakis M, Budtz-Jørgensen E, et al.: Prevalence, birth incidence, and penetrance of von Hippel-Lindau disease (vHL) in Denmark. Eur J Hum Genet 25 (3): 301-307, 2017.

- Evans DG, Howard E, Giblin C, et al.: Birth incidence and prevalence of tumor-prone syndromes: estimates from a UK family genetic register service. Am J Med Genet A 152A (2): 327-32, 2010.

- Neumann HP, Wiestler OD: Clustering of features of von Hippel-Lindau syndrome: evidence for a complex genetic locus. Lancet 337 (8749): 1052-4, 1991.

- Poulsen ML, Budtz-Jørgensen E, Bisgaard ML: Surveillance in von Hippel-Lindau disease (vHL). Clin Genet 77 (1): 49-59, 2010.

- Zhang K, Qiu J, Yang W, et al.: Clinical characteristics and risk factors for survival in affected offspring of von Hippel-Lindau disease patients. J Med Genet 59 (10): 951-956, 2022.

- Reich M, Jaegle S, Neumann-Haefelin E, et al.: Genotype-phenotype correlation in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Acta Ophthalmol 99 (8): e1492-e1500, 2021.

- Salama Y, Albanyan S, Szybowska M, et al.: Comprehensive characterization of a Canadian cohort of von Hippel-Lindau disease patients. Clin Genet 96 (5): 461-467, 2019.

- Brauch H, Kishida T, Glavac D, et al.: Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease with pheochromocytoma in the Black Forest region of Germany: evidence for a founder effect. Hum Genet 95 (5): 551-6, 1995.

- Hoffman MA, Ohh M, Yang H, et al.: von Hippel-Lindau protein mutants linked to type 2C VHL disease preserve the ability to downregulate HIF. Hum Mol Genet 10 (10): 1019-27, 2001.

- Sgambati MT, Stolle C, Choyke PL, et al.: Mosaicism in von Hippel-Lindau disease: lessons from kindreds with germline mutations identified in offspring with mosaic parents. Am J Hum Genet 66 (1): 84-91, 2000.

- Austin KD, Hall JG: Nontraditional inheritance. Pediatr Clin North Am 39 (2): 335-48, 1992.

- Ang SO, Chen H, Hirota K, et al.: Disruption of oxygen homeostasis underlies congenital Chuvash polycythemia. Nat Genet 32 (4): 614-21, 2002.

- Pastore YD, Jelinek J, Ang S, et al.: Mutations in the VHL gene in sporadic apparently congenital polycythemia. Blood 101 (4): 1591-5, 2003.

- Cario H, Schwarz K, Jorch N, et al.: Mutations in the von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) tumor suppressor gene and VHL-haplotype analysis in patients with presumable congenital erythrocytosis. Haematologica 90 (1): 19-24, 2005.

- Popova T, Hebert L, Jacquemin V, et al.: Germline BAP1 mutations predispose to renal cell carcinomas. Am J Hum Genet 92 (6): 974-80, 2013.

- Farley MN, Schmidt LS, Mester JL, et al.: A novel germline mutation in BAP1 predisposes to familial clear-cell renal cell carcinoma. Mol Cancer Res 11 (9): 1061-71, 2013.

- Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network: Comprehensive molecular characterization of clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Nature 499 (7456): 43-9, 2013.

- Benusiglio PR, Couvé S, Gilbert-Dussardier B, et al.: A germline mutation in PBRM1 predisposes to renal cell carcinoma. J Med Genet 52 (6): 426-30, 2015.

Molecular Biology

The VHLtumor suppressor gene encodes two proteins: a 213 amino acid protein (pVHL30) and a 154 amino acid protein, which is the product of internal translation.[

HIF1-Alpha and HIF2-Alpha

pVHL regulates protein levels of HIF1-alpha and HIF2-alpha in the cell by acting as a substrate recognition site for HIF as part of an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex.[

Hypoxia inactivates prolyl hydroxylases, leading to lack of HIF hydroxylation. Nonhydroxylated HIF1-alpha and HIF2-alpha are not bound to the VHL protein complex for ubiquitination, and therefore, accumulate. The resulting constitutively high levels of HIF1-alpha and HIF2-alpha drive increased transcription of a variety of genes, including growth and angiogenic factors, enzymes of the intermediary metabolism, and genes promoting stemness-like cellular phenotypes.[

HIF1-alpha and HIF2-alpha possess distinct and partially contrasting functional characteristics. In the context of renal cell carcinoma (RCC), it appears that the EPAS1 gene, also known as HIF2A, acts as an oncogene, and HIF1A acts as a tumor suppressor gene. HIF2-alpha may preferentially upregulate Myc activity, whereas HIF1-alpha may inhibit Myc activity.[

Numerous studies using xenografted or transgenic animal models have shown that inactivation of HIF2-alpha by pVHL is necessary and sufficient for tumor suppression by the pVHL proteins. HIF2-alpha is now an established therapeutic target for von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL)-related malignancies.[

Microtubule Regulation and Cilia Centrosome Control

Emerging data point to the importance of pVHL-mediated control of the primary cilium and the cilia centrosome cycle. The nonmotile primary cilium acts as a mechanosensor, regulates cell signaling, and controls cellular entry into mitosis.[

Cell Cycle Control

pVHL reintroduction induces cell cycle arrest and p27 upregulation after serum withdrawal in VHL-null cell lines.[

Extracellular Matrix Control

Functional pVHL is needed for appropriate assembly of an extracellular fibronectin matrix.[

Regulation of Oncogenic Autophagy

In clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), oncogenic autophagy dependent on microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 alpha and beta (LC3A and LC3B) is stimulated by activity of the transient receptor potential melastatin 3 (TRPM3) channel through multiple complementary mechanisms. The VHL tumor suppressor represses this oncogenic autophagy in a coordinated manner through the activity of miR-204, which is expressed from intron 6 of the gene encoding TRPM3. TRPM3 represents an actionable target for ccRCC treatment.[

Animal Models of VHL

Vhl-knockout mice die in utero. Heterozygous Vhl mice develop vascular liver lesions reminiscent of hemangioblastomas.[

References:

- Iliopoulos O, Ohh M, Kaelin WG: pVHL19 is a biologically active product of the von Hippel-Lindau gene arising from internal translation initiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 (20): 11661-6, 1998.

- Pause A, Lee S, Lonergan KM, et al.: The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene is required for cell cycle exit upon serum withdrawal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95 (3): 993-8, 1998.

- Kurban G, Hudon V, Duplan E, et al.: Characterization of a von Hippel Lindau pathway involved in extracellular matrix remodeling, cell invasion, and angiogenesis. Cancer Res 66 (3): 1313-9, 2006.

- Thoma CR, Toso A, Gutbrodt KL, et al.: VHL loss causes spindle misorientation and chromosome instability. Nat Cell Biol 11 (8): 994-1001, 2009.

- Maxwell PH, Wiesener MS, Chang GW, et al.: The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 399 (6733): 271-5, 1999.

- Ivan M, Kondo K, Yang H, et al.: HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science 292 (5516): 464-8, 2001.

- Jaakkola P, Mole DR, Tian YM, et al.: Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 292 (5516): 468-72, 2001.

- Keith B, Johnson RS, Simon MC: HIF1α and HIF2α: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat Rev Cancer 12 (1): 9-22, 2012.

- Gordan JD, Bertout JA, Hu CJ, et al.: HIF-2alpha promotes hypoxic cell proliferation by enhancing c-myc transcriptional activity. Cancer Cell 11 (4): 335-47, 2007.

- Koh MY, Lemos R, Liu X, et al.: The hypoxia-associated factor switches cells from HIF-1α- to HIF-2α-dependent signaling promoting stem cell characteristics, aggressive tumor growth and invasion. Cancer Res 71 (11): 4015-27, 2011.

- Koh MY, Darnay BG, Powis G: Hypoxia-associated factor, a novel E3-ubiquitin ligase, binds and ubiquitinates hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha, leading to its oxygen-independent degradation. Mol Cell Biol 28 (23): 7081-95, 2008.

- Monzon FA, Alvarez K, Peterson L, et al.: Chromosome 14q loss defines a molecular subtype of clear-cell renal cell carcinoma associated with poor prognosis. Mod Pathol 24 (11): 1470-9, 2011.

- Kondo K, Klco J, Nakamura E, et al.: Inhibition of HIF is necessary for tumor suppression by the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Cancer Cell 1 (3): 237-46, 2002.

- Kondo K, Kim WY, Lechpammer M, et al.: Inhibition of HIF2alpha is sufficient to suppress pVHL-defective tumor growth. PLoS Biol 1 (3): E83, 2003.

- Zimmer M, Doucette D, Siddiqui N, et al.: Inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor is sufficient for growth suppression of VHL-/- tumors. Mol Cancer Res 2 (2): 89-95, 2004.

- Zimmer M, Ebert BL, Neil C, et al.: Small-molecule inhibitors of HIF-2a translation link its 5'UTR iron-responsive element to oxygen sensing. Mol Cell 32 (6): 838-48, 2008.

- Metelo AM, Noonan HR, Li X, et al.: Pharmacological HIF2α inhibition improves VHL disease-associated phenotypes in zebrafish model. J Clin Invest 125 (5): 1987-97, 2015.

- Scheuermann TH, Li Q, Ma HW, et al.: Allosteric inhibition of hypoxia inducible factor-2 with small molecules. Nat Chem Biol 9 (4): 271-6, 2013.

- Pan J, Snell W: The primary cilium: keeper of the key to cell division. Cell 129 (7): 1255-7, 2007.

- Simons M, Walz G: Polycystic kidney disease: cell division without a c(l)ue? Kidney Int 70 (5): 854-64, 2006.

- Thoma CR, Frew IJ, Hoerner CR, et al.: pVHL and GSK3beta are components of a primary cilium-maintenance signalling network. Nat Cell Biol 9 (5): 588-95, 2007.

- Hergovich A, Lisztwan J, Barry R, et al.: Regulation of microtubule stability by the von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor protein pVHL. Nat Cell Biol 5 (1): 64-70, 2003.

- Hergovich A, Lisztwan J, Thoma CR, et al.: Priming-dependent phosphorylation and regulation of the tumor suppressor pVHL by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Mol Cell Biol 26 (15): 5784-96, 2006.

- Roe JS, Kim HR, Hwang IY, et al.: von Hippel-Lindau protein promotes Skp2 destabilization on DNA damage. Oncogene 30 (28): 3127-38, 2011.

- Kim J, Jonasch E, Alexander A, et al.: Cytoplasmic sequestration of p27 via AKT phosphorylation in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 15 (1): 81-90, 2009.

- Roe JS, Youn HD: The positive regulation of p53 by the tumor suppressor VHL. Cell Cycle 5 (18): 2054-6, 2006.

- Roe JS, Kim H, Lee SM, et al.: p53 stabilization and transactivation by a von Hippel-Lindau protein. Mol Cell 22 (3): 395-405, 2006.

- Ohh M, Yauch RL, Lonergan KM, et al.: The von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor protein is required for proper assembly of an extracellular fibronectin matrix. Mol Cell 1 (7): 959-68, 1998.

- Lolkema MP, Gervais ML, Snijckers CM, et al.: Tumor suppression by the von Hippel-Lindau protein requires phosphorylation of the acidic domain. J Biol Chem 280 (23): 22205-11, 2005.

- Hall DP, Cost NG, Hegde S, et al.: TRPM3 and miR-204 establish a regulatory circuit that controls oncogenic autophagy in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell 26 (5): 738-53, 2014.

- Mikhaylova O, Stratton Y, Hall D, et al.: VHL-regulated MiR-204 suppresses tumor growth through inhibition of LC3B-mediated autophagy in renal clear cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell 21 (4): 532-46, 2012.

- Haase VH, Glickman JN, Socolovsky M, et al.: Vascular tumors in livers with targeted inactivation of the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98 (4): 1583-8, 2001.

- Frew IJ, Thoma CR, Georgiev S, et al.: pVHL and PTEN tumour suppressor proteins cooperatively suppress kidney cyst formation. EMBO J 27 (12): 1747-57, 2008.

- Hickey MM, Lam JC, Bezman NA, et al.: von Hippel-Lindau mutation in mice recapitulates Chuvash polycythemia via hypoxia-inducible factor-2alpha signaling and splenic erythropoiesis. J Clin Invest 117 (12): 3879-89, 2007.

- Varela I, Tarpey P, Raine K, et al.: Exome sequencing identifies frequent mutation of the SWI/SNF complex gene PBRM1 in renal carcinoma. Nature 469 (7331): 539-42, 2011.

- Dalgliesh GL, Furge K, Greenman C, et al.: Systematic sequencing of renal carcinoma reveals inactivation of histone modifying genes. Nature 463 (7279): 360-3, 2010.

- Peña-Llopis S, Vega-Rubín-de-Celis S, Liao A, et al.: BAP1 loss defines a new class of renal cell carcinoma. Nat Genet 44 (7): 751-9, 2012.

Clinical Manifestations

Age Ranges and Cumulative Risk of Different Syndrome-Related Neoplasms

The age of onset for von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) varies both between different families and between members of the same family. This fact informs the guidelines for starting age and frequency of presymptomatic surveillance examinations. Of all VHL manifestations, retinal hemangioblastomas and pheochromocytomas (PHEOs) have the youngest age of onset; hence, targeted screening is recommended in children younger than 10 years. At least one study has demonstrated that the incidence of new lesions varies depending on patient age, the underlying pathogenic variant, and the organ involved.[

| Neoplasm | Mean Age (Range) in y | Cumulative Risk (%) |

|---|---|---|

| PHEO = pheochromocytoma | ||

| a Adapted from Choyke et al.[ |

||

| b Limited data are available for cystadenomas of the broad/round ligament and epididymis. | ||

| Renal cell carcinoma | 37 (16–67) | 24–45 |

| PHEO | 30 (5–58) | 10–20 |

| Pancreatic tumor or cyst | 36 (5–70) | 35–70 |

| Retinal hemangioblastoma | 25 (1–67) | 25–60 |

| Cerebellar hemangioblastoma | 33 (9–78) | 44–72 |

| Brainstem hemangioblastoma | 32 (12–46) | 10–25 |

| Spinal cord hemangioblastoma | 33 (12–66) | 13–50 |

| Endolymphatic sac tumor | 22 (12–50) | 10 |

For more information, see the

References:

- Binderup ML, Budtz-Jørgensen E, Bisgaard ML: Risk of new tumors in von Hippel-Lindau patients depends on age and genotype. Genet Med 18 (1): 89-97, 2016.

- Choyke PL, Glenn GM, Walther MM, et al.: von Hippel-Lindau disease: genetic, clinical, and imaging features. Radiology 194 (3): 629-42, 1995.

- Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, et al.: von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet 361 (9374): 2059-67, 2003.

Tissue Manifestations

Renal Manifestations

More than 55% of individuals with von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) only develop multiple renal cell cysts. VHL-associated renal cell carcinomas (RCCs) are characteristically multifocal and bilateral. These RCCs present as masses with both cystic and solid characteristics.[

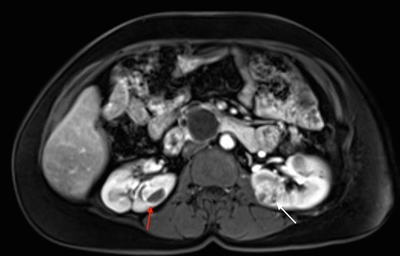

Figure 1. von Hippel-Lindau disease–associated renal cell cancers are characteristically multifocal and bilateral and present as combined cystic and solid masses. The red arrow shows a lesion with a solid and cystic component, and the white arrow shows a predominantly solid lesion.

Tumors larger than 3 cm may increase in grade as they grow, and metastasis may occur.[

Retinal Hemangioblastomas

Retinal manifestations, which were first reported more than a century ago, were one of the first recognized VHL features. Retinal hemangioblastomas (also known as capillary retinal angiomas) are one of the most common manifestations of VHL and are present in more than 50% of patients.[

Retinal hemangioblastomas occur most frequently in the periphery of the retina. They can also occur in other locations like the optic nerve, which is a more difficult area to treat. Retinal hemangioblastomas are bright orange spherical tumors that are supplied by a tortuous vascular supply. Nearly 50% of patients have bilateral retinal hemangioblastomas.[

Longitudinal studies help explain the natural history of these tumors. If left untreated, retinal hemangioblastomas can be a major source of morbidity in patients with VHL. Approximately 8% of patients [

Cerebellar and Spinal Hemangioblastomas

Hemangioblastomas are the most common disease manifestation in patients with VHL, affecting more than 70% of individuals. A prospective study assessed the natural history of hemangioblastomas.[

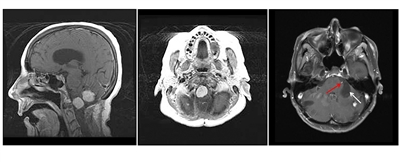

Figure 2. Hemangioblastomas are the most common disease manifestation in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. The left panel shows a sagittal view of brainstem and cerebellar lesions. The middle panel shows an axial view of a brainstem lesion. The right panel shows a cerebellar lesion (red arrow) with a dominant cystic component (white arrow).

Figure 3. Hemangioblastomas are the most common disease manifestation in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Multiple spinal cord hemangioblastomas are shown.

Pheochromocytomas and Paragangliomas

The rate of pheochromocytoma (PHEO) formation in the VHL patient population is 25% to 30%.[

PGLs are rare in VHL patients but can occur in the head and neck or in the abdomen.[

The mean age at diagnosis of VHL-related PHEOs and PGLs is approximately 30 years.[

Pancreatic Manifestations

Patients with VHL may develop multiple serous cystadenomas, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), and simple pancreatic cysts.[

Pancreatic cysts and cystadenomas are not malignant, but pancreatic NETs possess malignant characteristics.[

Endolymphatic Sac Tumors (ELSTs)

ELSTs are adenomatous tumors arising from the endolymphatic duct or sac within the posterior part of the petrous bone.[

ELSTs are an important cause of morbidity in VHL patients. ELSTs evident on imaging are associated with a variety of symptoms, including hearing loss (95% of patients), tinnitus (92%), vestibular symptoms (such as vertigo or disequilibrium) (62%), aural fullness (29%), and facial paresis (8%).[

Hearing loss related to ELSTs is typically irreversible; serial imaging to enable early detection of ELSTs in asymptomatic patients and resection of radiologically evident lesions are important components in the management of VHL patients.[

Broad/Round Ligament Papillary Cystadenomas

Tumors of the broad ligament can occur in females with VHL and are known as papillary cystadenomas. These tumors are extremely rare, and fewer than 20 have been reported in the literature.[

Epididymal Cystadenomas

Fluid-filled epididymal cysts, or spermatoceles, are very common in adult men. In VHL, the epididymis can contain more complex cystic neoplasms known as papillary cystadenomas, which are rare in the general population. More than one-third of all cases of epididymal cystadenomas reported in the literature and most cases of bilateral cystadenomas have been reported in patients with VHL.[

In a small series, histological analysis did not reveal features typically associated with malignancy, such as mitotic figures, nuclear pleomorphism, and necrosis. Lesions were strongly positive for CK7 and negative for RCC. Carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) was positive in all tumors. PAX8 was positive in most cases. These features were reminiscent of clear cell papillary RCC, a relatively benign form of RCC without known metastatic potential.[

References:

- Choyke PL, Glenn GM, Walther MM, et al.: The natural history of renal lesions in von Hippel-Lindau disease: a serial CT study in 28 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 159 (6): 1229-34, 1992.

- Poston CD, Jaffe GS, Lubensky IA, et al.: Characterization of the renal pathology of a familial form of renal cell carcinoma associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease: clinical and molecular genetic implications. J Urol 153 (1): 22-6, 1995.

- Walther MM, Choyke PL, Glenn G, et al.: Renal cancer in families with hereditary renal cancer: prospective analysis of a tumor size threshold for renal parenchymal sparing surgery. J Urol 161 (5): 1475-9, 1999.

- Walther MM, Lubensky IA, Venzon D, et al.: Prevalence of microscopic lesions in grossly normal renal parenchyma from patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease, sporadic renal cell carcinoma and no renal disease: clinical implications. J Urol 154 (6): 2010-4; discussion 2014-5, 1995.

- Chew EY: Ocular manifestations of von Hippel-Lindau disease: clinical and genetic investigations. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 103: 495-511, 2005.

- Choyke PL, Glenn GM, Walther MM, et al.: von Hippel-Lindau disease: genetic, clinical, and imaging features. Radiology 194 (3): 629-42, 1995.

- Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, et al.: von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet 361 (9374): 2059-67, 2003.

- Dollfus H, Massin P, Taupin P, et al.: Retinal hemangioblastoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease: a clinical and molecular study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 43 (9): 3067-74, 2002.

- Wong WT, Agrón E, Coleman HR, et al.: Clinical characterization of retinal capillary hemangioblastomas in a large population of patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Ophthalmology 115 (1): 181-8, 2008.

- Binderup MLM, Stendell AS, Galanakis M, et al.: Retinal hemangioblastoma: prevalence, incidence and frequency of underlying von Hippel-Lindau disease. Br J Ophthalmol 102 (7): 942-947, 2018.

- Kreusel KM, Bechrakis NE, Krause L, et al.: Retinal angiomatosis in von Hippel-Lindau disease: a longitudinal ophthalmologic study. Ophthalmology 113 (8): 1418-24, 2006.

- Schmidt D, Neumann HP: Retinal vascular hamartoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Arch Ophthalmol 113 (9): 1163-7, 1995.

- Wittström E, Nordling M, Andréasson S: Genotype-phenotype correlations, and retinal function and structure in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Ophthalmic Genet 35 (2): 91-106, 2014.

- Reich M, Jaegle S, Neumann-Haefelin E, et al.: Genotype-phenotype correlation in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Acta Ophthalmol 99 (8): e1492-e1500, 2021.

- Toy BC, Agrón E, Nigam D, et al.: Longitudinal analysis of retinal hemangioblastomatosis and visual function in ocular von Hippel-Lindau disease. Ophthalmology 119 (12): 2622-30, 2012.

- Huntoon K, Wu T, Elder JB, et al.: Biological and clinical impact of hemangioblastoma-associated peritumoral cysts in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg 124 (4): 971-6, 2016.

- Kanno H, Kuratsu J, Nishikawa R, et al.: Clinical features of patients bearing central nervous system hemangioblastoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 155 (1): 1-7, 2013.

- Lonser RR, Butman JA, Huntoon K, et al.: Prospective natural history study of central nervous system hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg 120 (5): 1055-62, 2014.

- Walther MM, Reiter R, Keiser HR, et al.: Clinical and genetic characterization of pheochromocytoma in von Hippel-Lindau families: comparison with sporadic pheochromocytoma gives insight into natural history of pheochromocytoma. J Urol 162 (3 Pt 1): 659-64, 1999.

- Aufforth RD, Ramakant P, Sadowski SM, et al.: Pheochromocytoma Screening Initiation and Frequency in von Hippel-Lindau Syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100 (12): 4498-504, 2015.

- Welander J, Söderkvist P, Gimm O: Genetics and clinical characteristics of hereditary pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas. Endocr Relat Cancer 18 (6): R253-76, 2011.

- Eisenhofer G, Walther MM, Huynh TT, et al.: Pheochromocytomas in von Hippel-Lindau syndrome and multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 display distinct biochemical and clinical phenotypes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86 (5): 1999-2008, 2001.

- Zbar B, Kishida T, Chen F, et al.: Germline mutations in the Von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) gene in families from North America, Europe, and Japan. Hum Mutat 8 (4): 348-57, 1996.

- Chen F, Slife L, Kishida T, et al.: Genotype-phenotype correlation in von Hippel-Lindau disease: identification of a mutation associated with VHL type 2A. J Med Genet 33 (8): 716-7, 1996.

- Friedrich CA: Genotype-phenotype correlation in von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 10 (7): 763-7, 2001.

- Eisenhofer G, Vocke CD, Elkahloun A, et al.: Genetic screening for von Hippel-Lindau gene mutations in non-syndromic pheochromocytoma: low prevalence and false-positives or misdiagnosis indicate a need for caution. Horm Metab Res 44 (5): 343-8, 2012.

- Shuch B, Ricketts CJ, Metwalli AR, et al.: The genetic basis of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: implications for management. Urology 83 (6): 1225-32, 2014.

- Eisenhofer G, Timmers HJ, Lenders JW, et al.: Age at diagnosis of pheochromocytoma differs according to catecholamine phenotype and tumor location. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96 (2): 375-84, 2011.

- Charlesworth M, Verbeke CS, Falk GA, et al.: Pancreatic lesions in von Hippel-Lindau disease? A systematic review and meta-synthesis of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg 16 (7): 1422-8, 2012.

- Libutti SK, Choyke PL, Bartlett DL, et al.: Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors associated with von Hippel Lindau disease: diagnostic and management recommendations. Surgery 124 (6): 1153-9, 1998.

- Blansfield JA, Choyke L, Morita SY, et al.: Clinical, genetic and radiographic analysis of 108 patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) manifested by pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PNETs). Surgery 142 (6): 814-8; discussion 818.e1-2, 2007.

- Manski TJ, Heffner DK, Glenn GM, et al.: Endolymphatic sac tumors. A source of morbid hearing loss in von Hippel-Lindau disease. JAMA 277 (18): 1461-6, 1997.

- Choo D, Shotland L, Mastroianni M, et al.: Endolymphatic sac tumors in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg 100 (3): 480-7, 2004.

- Megerian CA, Haynes DS, Poe DS, et al.: Hearing preservation surgery for small endolymphatic sac tumors in patients with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Otol Neurotol 23 (3): 378-87, 2002.

- Kim HJ, Butman JA, Brewer C, et al.: Tumors of the endolymphatic sac in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease: implications for their natural history, diagnosis, and treatment. J Neurosurg 102 (3): 503-12, 2005.

- Lonser RR, Kim HJ, Butman JA, et al.: Tumors of the endolymphatic sac in von Hippel-Lindau disease. N Engl J Med 350 (24): 2481-6, 2004.

- Nogales FF, Goyenaga P, Preda O, et al.: An analysis of five clear cell papillary cystadenomas of mesosalpinx and broad ligament: four associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease and one aggressive sporadic type. Histopathology 60 (5): 748-57, 2012.

- Cox R, Vang R, Epstein JI: Papillary cystadenoma of the epididymis and broad ligament: morphologic and immunohistochemical overlap with clear cell papillary renal cell carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol 38 (5): 713-8, 2014.

- Brady A, Nayar A, Cross P, et al.: A detailed immunohistochemical analysis of 2 cases of papillary cystadenoma of the broad ligament: an extremely rare neoplasm characteristic of patients with von hippel-lindau disease. Int J Gynecol Pathol 31 (2): 133-40, 2012.

- Odrzywolski KJ, Mukhopadhyay S: Papillary cystadenoma of the epididymis. Arch Pathol Lab Med 134 (4): 630-3, 2010.

- Uppuluri S, Bhatt S, Tang P, et al.: Clear cell papillary cystadenoma with sonographic and histopathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med 25 (11): 1451-3, 2006.

- Vijayvargiya M, Jain D, Mathur SR, et al.: Papillary cystadenoma of the epididymis associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease diagnosed on fine needle aspiration cytology. Cytopathology 25 (4): 279-81, 2014.

Genetic Risk Assessment for von Hippel-Lindau Disease (VHL)

The primary risk factor for VHL (or any hereditary forms of renal cancer) is an affected family member. Risk assessment should also consider gender and age for specific VHL-related neoplasms. For example, pheochromocytomas (PHEOs) may develop in early childhood,[

Each child of an individual with VHL has a 50% chance of inheriting the VHLvariant allele from the affected parent.

Clinical Diagnosis of VHL

Diagnosis of VHL is frequently based on clinical criteria. If there is family history of VHL, a previously unevaluated family member can be clinically diagnosed with VHL if this person presents with one or more VHL-related tumors (e.g., CNS/retinal hemangioblastomas, PHEOs, ccRCCs, or endolymphatic sac tumors). If a patient does not have a family history of VHL, he/she must meet one of the following criteria: (1) two or more CNS hemangioblastomas, or (2) one CNS hemangioblastoma and either (a) a visceral tumor or (b) an endolymphatic sac tumor. For more information about VHL diagnostic details, see

In 1998, all germline pathogenic variants identified in a cohort of 93 VHL families were reported. Since then, VHL diagnosis has been based on a combination of the following: (1) identifying clinical VHL-associated manifestations, and (2) conducting genetic testing for VHL pathogenic variants identified within families. This diagnostic strategy can differ for individual family members.

| Family History of VHL | Genetic Testing | Scenarios for Clinical Diagnosis | Requirements for Clinical Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNS = central nervous system; ccRCC = clear cell renal cell carcinoma; PHEO = pheochromocytoma. | |||

| Adapted and updated from Glenn et al.[ |

|||

| With a family history of VHL | Test DNA for the sameVHLpathogenic variant as previously identified in an affected biological relative(s) | When theVHLpathogenic variant in a biological relative is unknown | At least one of the following is required for clinical diagnosis: |

| - Epididymal or broad ligament cystadenoma | |||

| - CNS hemangioblastoma | |||

| - Multifocal ccRCC | |||

| - PHEO | |||

| - Retinal hemangioblastoma | |||

| - Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor | |||

| - Pancreatic cysts and/or cystadenoma | |||

| - Endolymphatic sac tumor | |||

| Without a family history of VHL | Genetic test results may be negative if theVHLpathogenic variant occurred postzygotically (e.g.,VHLmosaicism) | When theVHLpathogenic variant is unknown or germline negative, but there are clinical signs of VHL | At least one of the following is required for clinical diagnosis: |

| - CNS hemangioblastoma | |||

| - Retinal hemangioblastoma | |||

| If only one of the above is present, then one of the following is also required for a clinical diagnosis: | |||

| - ccRCC | |||

| - PHEO | |||

| - Pancreatic cysts and/or cystadenoma | |||

| - Endolymphatic sac tumor | |||

| - Epididymal or broad ligament cystadenoma | |||

Genetic Testing in VHL

It is recommended that at-risk family members be informed that genetic testing for VHL is available. A family member with a clinical diagnosis of VHL, or one who is showing signs/symptoms of VHL, is generally offered genetic testing first. Germline pathogenic variants in VHL are detected in more than 99% of families affected by VHL. Approximately one-third of these families have either a partial or complete deletion of the VHL gene.[

Sequence analysis of all three exons detects single nucleotide variants in the VHLgene (~72% of all pathogenic variants).[

Genetic counseling is provided before genetic testing. Such counseling includes a discussion of the medical, economic, and psychosocial implications for the patient and his/her blood relatives. After genetic counseling occurs, the patient may choose to proceed with genetic testing, after providing informed consent. Additional genetic counseling is given when results are reported to the patient. When a VHL pathogenic variant is identified in a family, biological relatives who test negative for this variant are not carriers of the trait (i.e., they are true negatives) and are not predisposed to VHL manifestations. Moreover, the children of true-negative family members are also not at risk of developing VHL. Clinical testing throughout their lifetimes is, therefore, unnecessary.[

Genetic Diagnosis in VHL

A germline pathogenic variant in the VHL gene is considered a genetic diagnosis.

This finding predisposes an individual to clinical VHL and confers a 50% risk for offspring to inherit the VHL pathogenic variant. Approximately 400 unique pathogenic variants in the VHL gene have been associated with clinical VHL, and their presence verifies the disease-causing capability of the variant. The diagnostic genetic evaluation in a previously untested family generally begins with a clinically diagnosed individual. If a VHL pathogenic variant is identified, that specific pathogenic variant becomes the DNA marker for which other biological relatives are tested. Some individuals may meet VHL clinical criteria for diagnosis but do not test positive for a VHL pathogenic variant. When these individuals also do not have family history of VHL, a de novo pathogenic variant or mosaicism may be present. The latter may be detected by performing genetic testing on other bodily tissues, such as skin fibroblasts or exfoliated buccal cells. For more information, see the

References:

- Choyke PL, Glenn GM, Walther MM, et al.: von Hippel-Lindau disease: genetic, clinical, and imaging features. Radiology 194 (3): 629-42, 1995.

- Maher ER, Yates JR, Harries R, et al.: Clinical features and natural history of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Q J Med 77 (283): 1151-63, 1990.

- Lonser RR, Glenn GM, Walther M, et al.: von Hippel-Lindau disease. Lancet 361 (9374): 2059-67, 2003.

- Pithukpakorn M, Glenn G: von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Community Oncology 1 (4): 232-43, 2004.

- Glenn GM, Daniel LN, Choyke P, et al.: Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease: distinct phenotypes suggest more than one mutant allele at the VHL locus. Hum Genet 87 (2): 207-10, 1991.

- Vocke CD, Ricketts CJ, Schmidt LS, et al.: Comprehensive characterization of Alu-mediated breakpoints in germline VHL gene deletions and rearrangements in patients from 71 VHL families. Hum Mutat 42 (5): 520-529, 2021.

- Stolle C, Glenn G, Zbar B, et al.: Improved detection of germline mutations in the von Hippel-Lindau disease tumor suppressor gene. Hum Mutat 12 (6): 417-23, 1998.

- Coppin L, Grutzmacher C, Crépin M, et al.: VHL mosaicism can be detected by clinical next-generation sequencing and is not restricted to patients with a mild phenotype. Eur J Hum Genet 22 (9): 1149-52, 2014.

Screening for Early Detection of VHL Manifestations

Screening guidelines have been suggested for various manifestations of VHL. In general, these recommendations are based on expert opinion and consensus, but most of these recommendations are not evidence-based. Several VHL screening and surveillance guidelines are available.[

| Examination/Test | Condition Screened For |

|---|---|

| CNS = central nervous system; IAC = internal auditory canal; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging. | |

| a Adapted from VHL Alliance.[ |

|

| b Age-appropriate history and physical examination includes the following: neurological examination, auditory/vestibuloneural questioning and testing, visual symptoms, catecholamine-excess symptom assessment (headaches, palpitations, diaphoresis, hyperactivity, anxiety, polyuria, and abdominal pain). | |

| History and physical examinationb | All conditions listed in this table |

| Dilated, in-person eye examination with ophthalmoscopy | Retinal hemangioblastoma |

| Blood pressure and pulse measurements, plasma free metanephrines or fractionated 24-hour urinary free metanephrines test | Pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma |

| MRI of brain and total spine with and without contrast | CNS hemangioblastoma |

| MRI of abdomen with and without contrast | Renal cell carcinoma, pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor/cyst |

| Audiological exam, MRI of IAC | Endolymphatic sac tumor |

Level of evidence: 5

Screening for PHEOs

PHEOs can be detected early when key tests like catecholamine/metanephrine levels and cross-sectional abdominal imaging are done. Most small (≤1 cm) PHEOs can have undetectable levels of catecholamines/metanephrines, and thus, these levels can increase with PHEO tumor progression.[

Biochemical testing for PHEOs

Biochemical testing is critical when evaluating individuals with VHL, since metabolite levels can often be elevated in the absence of anatomic imaging findings. Assessment begins in childhood, with some guidelines recommending initiation at age 5 years (

Imaging for PHEOs

Cross-sectional imaging is initiated early in the second decade of life to evaluate the kidneys, adrenal glands, and pancreas. Both magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) scans have excellent performance characteristics for detecting PHEOs, with a sensitivity greater than 90%.[

Screening for Endolymphatic Sac Tumors (ELSTs)

ELSTs can often cause permanent audiovestibular dysfunction. Early identification and treatment of these tumors may decrease morbidity significantly. ELST screening typically includes clinical assessment, audiogram, and imaging. The VHL Alliance's expert consensus guideline on screening recommendations for ELSTs is based on available evidence.[

References:

- Wolters WPG, Dreijerink KMA, Giles RH, et al.: Multidisciplinary integrated care pathway for von Hippel-Lindau disease. Cancer 128 (15): 2871-2879, 2022.

- Binderup MLM, Smerdel M, Borgwadt L, et al.: von Hippel-Lindau disease: Updated guideline for diagnosis and surveillance. Eur J Med Genet 65 (8): 104538, 2022.

- VHL Alliance: VHLA Suggested Active Surveillance Guidelines. Boston, MA: VHL Alliance, 2020.

Available online . Last accessed October 22, 2024. - Daniels AB, Tirosh A, Huntoon K, et al.: Guidelines for surveillance of patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease: Consensus statement of the International VHL Surveillance Guidelines Consortium and VHL Alliance. Cancer 129 (19): 2927-2940, 2023.

- Sanford T, Gomella PT, Siddiqui R, et al.: Long term outcomes for patients with von Hippel-Lindau and Pheochromocytoma: defining the role of active surveillance. Urol Oncol 39 (2): 134.e1-134.e8, 2021.

- Neary NM, King KS, Pacak K: Drugs and pheochromocytoma--don't be fooled by every elevated metanephrine. N Engl J Med 364 (23): 2268-70, 2011.

- Shuch B, Ricketts CJ, Metwalli AR, et al.: The genetic basis of pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: implications for management. Urology 83 (6): 1225-32, 2014.

- Čtvrtlík F, Koranda P, Schovánek J, et al.: Current diagnostic imaging of pheochromocytomas and implications for therapeutic strategy. Exp Ther Med 15 (4): 3151-3160, 2018.

- Ilias I, Pacak K: Current approaches and recommended algorithm for the diagnostic localization of pheochromocytoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89 (2): 479-91, 2004.

- Ilias I, Meristoudis G: Functional Imaging of Paragangliomas with an Emphasis on Von Hippel-Lindau-Associated Disease: A Mini Review. J Kidney Cancer VHL 4 (3): 30-36, 2017.

- Mehta GU, Kim HJ, Gidley PW, et al.: Endolymphatic Sac Tumor Screening and Diagnosis in von Hippel-Lindau Disease: A Consensus Statement. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base 83 (Suppl 2): e225-e231, 2022.

- Poulsen ML, Gimsing S, Kosteljanetz M, et al.: von Hippel-Lindau disease: surveillance strategy for endolymphatic sac tumors. Genet Med 13 (12): 1032-41, 2011.

- Butman JA, Nduom E, Kim HJ, et al.: Imaging detection of endolymphatic sac tumor-associated hydrops. J Neurosurg 119 (2): 406-11, 2013.

Management of Disease Manifestations

Management of Renal Tumors

Surgical interventions for renal tumors

The management of von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) has changed significantly as clinicians have learned how to balance the risk of cancer spread while minimizing renal morbidity. Some initial surgical series performed bilateral radical nephrectomies for renal tumors followed by renal transplant.[

Patients with VHL can have dozens of renal tumors. Therefore, resection of all evident renal disease may not be feasible. To minimize the morbidity of multiple surgical procedures, loss of kidney function, and the risk of distant progression, a method to balance overtreatment and undertreatment was sought. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) evaluated a specific tumor-size threshold to trigger surgical intervention. An evaluation of 52 patients with VHL or hereditary papillary renal carcinoma who were treated when their largest solid renal lesion reached 3 cm demonstrated no evidence of distant metastases or the need for renal replacement therapy after a median follow-up period of 60 months.[

Many patients with VHL develop new RCCs on an ongoing basis and may require further intervention. Adhesions and perinephric scarring make subsequent surgical procedures more challenging. While a radical nephrectomy could be considered, NSS remains the preferred approach, when feasible. While there may be a higher incidence of complications, repeat and salvage NSS can enable patients to maintain excellent renal function and provide promising oncological outcomes at the time of intermediate follow-up.[

Level of evidence: 3di

Ablative techniques for renal tumors

Thermal ablative techniques apply extreme heat or cold to a mass to destroy it. Cryoablation (CA) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) were introduced in the late 1990s to manage small renal masses.[

Thermal ablation may play an increasing role as salvage therapy for individuals with a high risk of morbidity from surgery. CA was evaluated as a salvage therapy in 14 patients to avoid the morbidity associated with repeated NSS. Results showed minimal change in renal function after treatment with CA. There was suspicion of recurrence in only 4 of 33 tumors (12.1%) after a median follow-up period of 37 months.[

In summary, the clinical applications of ablative techniques are not clearly defined in VHL, and surgery remains the most-studied intervention. The available clinical evidence suggests that ablative approaches are only recommended for small (≤3 cm), solid-enhancing renal masses in older patients with high operative risk—especially those facing salvage renal surgery because of a high complication rate. Young age, tumors larger than 4 cm, hilar tumors, and cystic lesions are relative contraindications for thermal ablation.[

Level of evidence: 3di

Management of Pheochromocytomas (PHEOs)

Surveillance of PHEOs

PHEOs can be a significant source of morbidity in patients with VHL because excess catecholamines can cause significant cardiovascular effects.[

Surgical interventions for PHEOs

Surgical resection is an important tool for managing PHEOs in individuals with VHL. It is important that all patients have detailed endocrine evaluations and preoperative alpha-blockades before surgical resection of PHEOs. Medications are often initiated and carefully titrated prior to surgery to prevent potentially life-threatening cardiovascular complications. For more information, see the

PHEOs in patients with VHL may be managed differently than in individuals with sporadic PHEOs or other hereditary cancer syndromes. Since PHEOs are multifocal and bilateral in individuals with VHL nearly 50% of the time, many patients have undergone bilateral adrenalectomy and have required lifelong steroid replacement.[

The possibility of partial adrenalectomy leaving residual cancer behind is a concern in patients with a malignant PHEO. However, in the VHL population, the malignancy rate of PHEOs is low (<5%).[

In a total adrenalectomy, the adrenal vein is usually divided early to limit catecholamine release during gland mobilization. However, in a partial adrenalectomy, dividing the adrenal vein can lead to venous congestion and gland compromise.[

Both open resection and laparoscopic surgical approaches are safe, but if feasible, laparoscopic removal of adrenal tissue is preferred.[

Management of Pancreatic Manifestations

VHL-related tumors, such as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), may be identified during incidental imaging or lifelong surveillance protocols.[

Workup and imaging for pancreatic manifestations

Pancreatic cysts are benign and rarely require intervention. Pancreatic cysts in VHL do not show enhancement on imaging and do not have malignant potential, regardless of size. Diffuse cystic disease of the pancreas rarely affects endocrine function. Infrequently, cystic replacement of the normal pancreas can lead to a loss of exocrine function. When bloating, cramping, diarrhea, or abdominal pain occurs with fatty meals, enzymatic studies on the stool could be employed to determine if exocrine supplementation is indicated. Solid or mixed pancreatic lesions require specialized evaluation and treatment because they may be cystadenomas or pancreatic NETs. Most pancreatic NETs are nonfunctional, but laboratory evaluation with biochemical markers, such as chromogranin A, could be considered during the workup or follow-up. Imaging evaluation with a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are both excellent modalities to characterize pancreatic lesions. Gallium Ga 68-DOTATATE positron emission tomography (PET)/CT has also been used to detect VHL-associated tumors.[

Surveillance of pancreatic manifestations

Serous cystadenomas do not have malignant potential and can be safely observed. Local obstruction of the bile duct or the pancreatic duct occur rarely with these lesions. Solid pancreatic NETs have a low metastatic potential. If they are localized, small, and asymptomatic, they can be safely observed without concerns. The duration and modality for pancreatic imaging is center-dependent, but general principles include performing imaging every 1 to 2 years with the same examination method to allow meaningful comparisons. Pancreatic lesions with slow doubling times, sizes less than 3 cm, and a lack of exon 3 pathogenic variants have the most favorable outcomes.[

Surgical interventions for pancreatic manifestations

Pancreatic cysts rarely need surgical intervention except when they exert a mass effect. Aspiration or decortication can be considered in these rare cases. Indications for surgery on pancreatic NETs can vary, but intervention is offered to lower the risk of dissemination. A review of the natural history of pancreatic NETs shows that these tumors may demonstrate nonlinear growth characteristics.[

Positive lymph nodes should be removed if they are found during surgery. Surgery is still considered for individuals with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic NETs if significant debulking can be offered. Additionally, metastatic liver lesions can often be treated with local ablative techniques or resection in select patients with VHL.

Management of Retinal Hemangioblastomas

Interventions for retinal hemangioblastomas

Treatment of retinal hemangioblastomas includes laser treatment, photodynamic therapy, and vitrectomy. Efforts have also been made to use either local or systemic therapy.

Laser photocoagulation

Laser photocoagulation is used extensively to treat retinal hemangioblastomas in patients with VHL. A retrospective review of 304 treated retinal hemangioblastomas in 100 eyes showed that laser photocoagulation had a control rate greater than 90% and was most effective in smaller lesions up to 1 disk diameter.[

Vitrectomy and retinectomy

Twenty-one patients with severe retinal detachment achieved varying degrees of visual preservation when treated with pars plana vitrectomy with posterior hyaloid detachment, epiretinal membrane dissection, and silicone oil/gas injection with retinectomy or photocoagulation/cryotherapy to remove the retinal hemangioblastoma.[

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy reduced macular edema in a case series of two patients with bilateral retinal hemangioblastomas.[

Intravitreal treatment

Intravitreal treatment with bevacizumab resulted in stabilization of retinal capillary hemangioblastomas for over 2 years in one case report [

Proton therapy

In a case study in which proton therapy was used on eight eyes (in eight patients), macular edema was resolved in seven of eight patients. All treated eyes had vision preserved after a median follow-up period of 84 months.[

Management of Central Nervous System (CNS) Hemangioblastomas

Surveillance of CNS hemangioblastomas

Many small lesions are found incidentally with screening, and patients may remain asymptomatic for a long time. In a study with a short-term follow-up period, 35.5% to 51% of CNS hemangioblastomas remained stable.[

In a National Institutes of Health series, researchers noted that patterns of growth for CNS hemangioblastomas can vary, with saltatory growth patterns occurring most often (72%).[

Another small series (n = 52) aimed to evaluate growth rates of CNS hemangioblastomas under surveillance. Researchers found that symptomatic presentation was the only independent predictor of growth.[

Surgical interventions for CNS hemangioblastomas

Surgical resection of cerebellar or spinal hemangioblastomas has been the standard treatment approach. While surgical resection of tumors is generally performed before the onset of neurological symptoms,[

Radiation therapy for CNS hemangioblastomas

Because patients may have multiple tumors and require several surgical procedures, external beam radiation therapy has emerged as an alternative when surgical resection is not feasible. Stereotactic radiosurgery is a commonly used approach for hemangioblastoma treatment.[

Management of Endolymphatic Sac Tumors (ELSTs)

There are limited data on the management of ELSTs, consisting largely of case series detailing surgical management of sporadic and VHL-associated tumors. Because audiovestibular compromise is not dependent on tumor size and can occur with small tumors, early intervention is generally preferred. Early intervention may also minimize the risk of invasion into surrounding structures and increase the probability of complete resection. A meta-analysis assessed outcomes from 82 studies that treated 252 tumors.[

VHL-Specific Systemic Therapy for Localized Disease

Patients with VHL often require multiple local treatments for their disease manifestations. Recurrent surgical intervention contributes to morbidity and can often cause irreversible damage to affected organs. Permanent loss of function can occur in the following organs:

- Visual impairment (retina).

- Chronic kidney disease (kidney).

- Adrenal insufficiency (adrenal glands).

- Diabetes and pancreatic exocrine deficiency (pancreas).

- Neurological complications such as motor or sensory deficits (brain and spine).

Researchers have sought a systemic therapy that can reduce or eliminate the need for local interventions. Understanding the biology of VHL has led to the development of targeted therapies that interfere with the downstream signaling cascade associated with tumorigenesis.[

Initial research on tanespimycin (17-AAG) therapy highlighted that some patients may not prefer intravenous administration of medication. The modest toxicity and poor tolerability associated with 17-AAG may deter healthy patients (with other surgical options) from using this treatment.[

While anti-VEGF therapy is administered systemically for most VHL-associated neoplasms, in VHL-associated retinal tumors, it can be delivered directly into the eye. Intravitreally-administered pegaptanib (an anti-VEGF therapy) was evaluated in five patients with VHL-associated retinal hemangioblastomas.[

Research targeting downstream consequences of HIF upregulation (due to inactivation of the VHL gene) have had only modest success. Hence, recent efforts have focused on targeting direct consequences of VHL loss. Multiple studies have demonstrated that multiple HIF molecules differentially regulate tumorigenesis, with HIF2 being the most critical mediator.[

VHL Management During Pregnancy

Two studies have examined the effect of pregnancy on hemangioblastoma progression in patients with VHL.[

References:

- Goldfarb DA, Neumann HP, Penn I, et al.: Results of renal transplantation in patients with renal cell carcinoma and von Hippel-Lindau disease. Transplantation 64 (12): 1726-9, 1997.

- Fetner CD, Barilla DE, Scott T, et al.: Bilateral renal cell carcinoma in von Hippel-Lindau syndrome: treatment with staged bilateral nephrectomy and hemodialysis. J Urol 117 (4): 534-6, 1977.

- Antony MB, Rompré-Brodeur A, Chaurasia A, et al.: Outcomes of and indications for renal transplantation in patients with von Hippel Lindau disease. Urol Oncol 41 (12): 487.e1-487.e6, 2023.

- Pearson JC, Weiss J, Tanagho EA: A plea for conservation of kidney in renal adenocarcinoma associated with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Urol 124 (6): 910-2, 1980.

- Loughlin KR, Gittes RF: Urological management of patients with von Hippel-Lindau's disease. J Urol 136 (4): 789-91, 1986.

- Steinbach F, Novick AC, Zincke H, et al.: Treatment of renal cell carcinoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease: a multicenter study. J Urol 153 (6): 1812-6, 1995.

- Walther MM, Thompson N, Linehan W: Enucleation procedures in patients with multiple hereditary renal tumors. World J Urol 13 (4): 248-50, 1995.

- Walther MM, Choyke PL, Glenn G, et al.: Renal cancer in families with hereditary renal cancer: prospective analysis of a tumor size threshold for renal parenchymal sparing surgery. J Urol 161 (5): 1475-9, 1999.

- Duffey BG, Choyke PL, Glenn G, et al.: The relationship between renal tumor size and metastases in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Urol 172 (1): 63-5, 2004.

- Peng X, Chen J, Wang J, et al.: Natural history of renal tumours in von Hippel-Lindau disease: a large retrospective study of Chinese patients. J Med Genet 56 (6): 380-387, 2019.

- Zhang J, Pan JH, Dong BJ, et al.: Active surveillance of renal masses in von Hippel-Lindau disease: growth rates and clinical outcome over a median follow-up period of 56 months. Fam Cancer 11 (2): 209-14, 2012.

- Jilg CA, Neumann HP, Gläsker S, et al.: Growth kinetics in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Urol Int 88 (1): 71-8, 2012.

- Neumann HP, Bender BU, Berger DP, et al.: Prevalence, morphology and biology of renal cell carcinoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease compared to sporadic renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 160 (4): 1248-54, 1998.

- Fadahunsi AT, Sanford T, Linehan WM, et al.: Feasibility and outcomes of partial nephrectomy for resection of at least 20 tumors in a single renal unit. J Urol 185 (1): 49-53, 2011.

- Choyke PL, Pavlovich CP, Daryanani KD, et al.: Intraoperative ultrasound during renal parenchymal sparing surgery for hereditary renal cancers: a 10-year experience. J Urol 165 (2): 397-400, 2001.

- Bratslavsky G, Liu JJ, Johnson AD, et al.: Salvage partial nephrectomy for hereditary renal cancer: feasibility and outcomes. J Urol 179 (1): 67-70, 2008.

- Johnson A, Sudarshan S, Liu J, et al.: Feasibility and outcomes of repeat partial nephrectomy. J Urol 180 (1): 89-93; discussion 93, 2008.

- Shuch B, Linehan WM, Bratslavsky G: Repeat partial nephrectomy: surgical, functional and oncological outcomes. Curr Opin Urol 21 (5): 368-75, 2011.

- Gill IS, Novick AC, Soble JJ, et al.: Laparoscopic renal cryoablation: initial clinical series. Urology 52 (4): 543-51, 1998.

- McGovern FJ, Wood BJ, Goldberg SN, et al.: Radio frequency ablation of renal cell carcinoma via image guided needle electrodes. J Urol 161 (2): 599-600, 1999.

- Campbell SC, Novick AC, Belldegrun A, et al.: Guideline for management of the clinical T1 renal mass. J Urol 182 (4): 1271-9, 2009.

- Walther MC, Shawker TH, Libutti SK, et al.: A phase 2 study of radio frequency interstitial tissue ablation of localized renal tumors. J Urol 163 (5): 1424-7, 2000.

- Shingleton WB, Sewell PE: Percutaneous renal cryoablation of renal tumors in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Urol 167 (3): 1268-70, 2002.

- Park BK, Kim CK: Percutaneous radio frequency ablation of renal tumors in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease: preliminary results. J Urol 183 (5): 1703-7, 2010.

- Chan VW, Lenton J, Smith J, et al.: Multimodal image-guided ablation on management of renal cancer in Von-Hippel-Lindau syndrome patients from 2004 to 2021 at a specialist centre: A longitudinal observational study. Eur J Surg Oncol 48 (3): 672-679, 2022.

- Joly D, Méjean A, Corréas JM, et al.: Progress in nephron sparing therapy for renal cell carcinoma and von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Urol 185 (6): 2056-60, 2011.

- Yang B, Autorino R, Remer EM, et al.: Probe ablation as salvage therapy for renal tumors in von Hippel-Lindau patients: the Cleveland Clinic experience with 3 years follow-up. Urol Oncol 31 (5): 686-92, 2013.

- Nguyen CT, Lane BR, Kaouk JH, et al.: Surgical salvage of renal cell carcinoma recurrence after thermal ablative therapy. J Urol 180 (1): 104-9; discussion 109, 2008.

- Karam JA, Wood CG, Compton ZR, et al.: Salvage surgery after energy ablation for renal masses. BJU Int 115 (1): 74-80, 2015.

- Kowalczyk KJ, Hooper HB, Linehan WM, et al.: Partial nephrectomy after previous radio frequency ablation: the National Cancer Institute experience. J Urol 182 (5): 2158-63, 2009.

- Shuch B, Singer EA, Bratslavsky G: The surgical approach to multifocal renal cancers: hereditary syndromes, ipsilateral multifocality, and bilateral tumors. Urol Clin North Am 39 (2): 133-48, v, 2012.

- Dominguez-Escrig JL, Sahadevan K, Johnson P: Cryoablation for small renal masses. Adv Urol : 479495, 2008.

- Aron M, Gill IS: Minimally invasive nephron-sparing surgery (MINSS) for renal tumours. Part II: probe ablative therapy. Eur Urol 51 (2): 348-57, 2007.

- Sanford T, Gomella PT, Siddiqui R, et al.: Long term outcomes for patients with von Hippel-Lindau and Pheochromocytoma: defining the role of active surveillance. Urol Oncol 39 (2): 134.e1-134.e8, 2021.

- Benhammou JN, Boris RS, Pacak K, et al.: Functional and oncologic outcomes of partial adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma in patients with von Hippel-Lindau syndrome after at least 5 years of followup. J Urol 184 (5): 1855-9, 2010.

- Baghai M, Thompson GB, Young WF, et al.: Pheochromocytomas and paragangliomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease: a role for laparoscopic and cortical-sparing surgery. Arch Surg 137 (6): 682-8; discussion 688-9, 2002.

- Brauckhoff M, Gimm O, Thanh PN, et al.: Critical size of residual adrenal tissue and recovery from impaired early postoperative adrenocortical function after subtotal bilateral adrenalectomy. Surgery 134 (6): 1020-7; discussion 1027-8, 2003.

- Walther MM, Keiser HR, Choyke PL, et al.: Management of hereditary pheochromocytoma in von Hippel-Lindau kindreds with partial adrenalectomy. J Urol 161 (2): 395-8, 1999.

- Fallon SC, Feig D, Lopez ME, et al.: The utility of cortical-sparing adrenalectomy in pheochromocytomas associated with genetic syndromes. J Pediatr Surg 48 (6): 1422-5, 2013.

- Roukounakis N, Dimas S, Kafetzis I, et al.: Is preservation of the adrenal vein mandatory in laparoscopic adrenal-sparing surgery? JSLS 11 (2): 215-8, 2007 Apr-Jun.

- Timmers HJ, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Mannelli M, et al.: Clinical aspects of SDHx-related pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Endocr Relat Cancer 16 (2): 391-400, 2009.

- Vargas HI, Kavoussi LR, Bartlett DL, et al.: Laparoscopic adrenalectomy: a new standard of care. Urology 49 (5): 673-8, 1997.

- Perrier ND, Kennamer DL, Bao R, et al.: Posterior retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy: preferred technique for removal of benign tumors and isolated metastases. Ann Surg 248 (4): 666-74, 2008.

- Dickson PV, Jimenez C, Chisholm GB, et al.: Posterior retroperitoneoscopic adrenalectomy: a contemporary American experience. J Am Coll Surg 212 (4): 659-65; discussion 665-7, 2011.

- Binderup ML, Bisgaard ML, Harbud V, et al.: Von Hippel-Lindau disease (vHL). National clinical guideline for diagnosis and surveillance in Denmark. 3rd edition. Dan Med J 60 (12): B4763, 2013.

- Kruizinga RC, Sluiter WJ, de Vries EG, et al.: Calculating optimal surveillance for detection of von Hippel-Lindau-related manifestations. Endocr Relat Cancer 21 (1): 63-71, 2014.

- Keutgen XM, Hammel P, Choyke PL, et al.: Evaluation and management of pancreatic lesions in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 13 (9): 537-49, 2016.

- Shell J, Tirosh A, Millo C, et al.: The utility of 68Gallium-DOTATATE PET/CT in the detection of von Hippel-Lindau disease associated tumors. Eur J Radiol 112: 130-135, 2019.

- Sadowski SM, Weisbrod AB, Ellis R, et al.: Prospective evaluation of the clinical utility of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose PET CT scanning in patients with von hippel-lindau-associated pancreatic lesions. J Am Coll Surg 218 (5): 997-1003, 2014.

- Blansfield JA, Choyke L, Morita SY, et al.: Clinical, genetic and radiographic analysis of 108 patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) manifested by pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PNETs). Surgery 142 (6): 814-8; discussion 818.e1-2, 2007.

- Tirosh A, Sadowski SM, Linehan WM, et al.: Association of VHL Genotype With Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor Phenotype in Patients With von Hippel-Lindau Disease. JAMA Oncol 4 (1): 124-126, 2018.

- Weisbrod AB, Kitano M, Thomas F, et al.: Assessment of tumor growth in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors in von Hippel Lindau syndrome. J Am Coll Surg 218 (2): 163-9, 2014.

- Libutti SK, Choyke PL, Bartlett DL, et al.: Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors associated with von Hippel Lindau disease: diagnostic and management recommendations. Surgery 124 (6): 1153-9, 1998.

- Krivosic V, Kamami-Levy C, Jacob J, et al.: Laser photocoagulation for peripheral retinal capillary hemangioblastoma in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Ophthalmol Retina 1 (1): 59-67, 2017.

Also available online . Last accessed October 22, 2024. - Gaudric A, Krivosic V, Duguid G, et al.: Vitreoretinal surgery for severe retinal capillary hemangiomas in von hippel-lindau disease. Ophthalmology 118 (1): 142-9, 2011.

- Krzystolik K, Stopa M, Kuprjanowicz L, et al.: PARS PLANA VITRECTOMY IN ADVANCED CASES OF VON HIPPEL-LINDAU EYE DISEASE. Retina 36 (2): 325-34, 2016.

- Papastefanou VP, Pilli S, Stinghe A, et al.: Photodynamic therapy for retinal capillary hemangioma. Eye (Lond) 27 (3): 438-42, 2013.

- Sachdeva R, Dadgostar H, Kaiser PK, et al.: Verteporfin photodynamic therapy of six eyes with retinal capillary haemangioma. Acta Ophthalmol 88 (8): e334-40, 2010.

- Ach T, Thiemeyer D, Hoeh AE, et al.: Intravitreal bevacizumab for retinal capillary haemangioma: longterm results. Acta Ophthalmol 88 (4): e137-8, 2010.

- Slim E, Antoun J, Kourie HR, et al.: Intravitreal bevacizumab for retinal capillary hemangioblastoma: A case series and literature review. Can J Ophthalmol 49 (5): 450-7, 2014.

- Wong WT, Liang KJ, Hammel K, et al.: Intravitreal ranibizumab therapy for retinal capillary hemangioblastoma related to von Hippel-Lindau disease. Ophthalmology 115 (11): 1957-64, 2008.

- von Buelow M, Pape S, Hoerauf H: Systemic bevacizumab treatment of a juxtapapillary retinal haemangioma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 85 (1): 114-6, 2007.

- Wackernagel W, Lackner EM, Pilz S, et al.: von Hippel-Lindau disease: treatment of retinal haemangioblastomas by targeted therapy with systemic bevacizumab. Acta Ophthalmol 88 (7): e271-2, 2010.

- Knickelbein JE, Jacobs-El N, Wong WT, et al.: Systemic Sunitinib Malate Treatment for Advanced Juxtapapillary Retinal Hemangioblastomas Associated with von Hippel-Lindau Disease. Ophthalmol Retina 1 (3): 181-187, 2017 May-Jun.

- Seibel I, Cordini D, Hager A, et al.: Long-term results after proton beam therapy for retinal papillary capillary hemangioma. Am J Ophthalmol 158 (2): 381-6, 2014.

- Byun J, Yoo HJ, Kim JH, et al.: Growth rate and fate of untreated hemangioblastomas: clinical assessment of the experience of a single institution. J Neurooncol 144 (1): 147-154, 2019.

- Lonser RR, Butman JA, Huntoon K, et al.: Prospective natural history study of central nervous system hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg 120 (5): 1055-62, 2014.

- Harati A, Satopää J, Mahler L, et al.: Early microsurgical treatment for spinal hemangioblastomas improves outcome in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Surg Neurol Int 3: 6, 2012.

- Asthagiri AR, Mehta GU, Butman JA, et al.: Long-term stability after multilevel cervical laminectomy for spinal cord tumor resection in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg Spine 14 (4): 444-52, 2011.

- Das JM, Kesavapisharady K, Sadasivam S, et al.: Microsurgical Treatment of Sporadic and von Hippel-Lindau Disease Associated Spinal Hemangioblastomas: A Single-Institution Experience. Asian Spine J 11 (4): 548-555, 2017.

- Kano H, Shuto T, Iwai Y, et al.: Stereotactic radiosurgery for intracranial hemangioblastomas: a retrospective international outcome study. J Neurosurg 122 (6): 1469-78, 2015.

- Asthagiri AR, Mehta GU, Zach L, et al.: Prospective evaluation of radiosurgery for hemangioblastomas in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Neuro Oncol 12 (1): 80-6, 2010.

- Liebenow B, Tatter A, Dezarn WA, et al.: Gamma Knife Stereotactic Radiosurgery favorably changes the clinical course of hemangioblastoma growth in von Hippel-Lindau and sporadic patients. J Neurooncol 142 (3): 471-478, 2019.

- Tang JD, Grady AJ, Nickel CJ, et al.: Systematic Review of Endolymphatic Sac Tumor Treatment and Outcomes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 168 (3): 282-290, 2023.

- Linehan WM, Pinto PA, Bratslavsky G, et al.: Hereditary kidney cancer: unique opportunity for disease-based therapy. Cancer 115 (10 Suppl): 2252-61, 2009.

- Shuch B: HIF2 Inhibition for von-Hippel Lindau Associated Kidney Cancer: Will Urology Lead or Follow? Urol Oncol 39 (5): 277-280, 2021.

- Jonasch E, McCutcheon IE, Waguespack SG, et al.: Pilot trial of sunitinib therapy in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. Ann Oncol 22 (12): 2661-6, 2011.

- Roma A, Maruzzo M, Basso U, et al.: First-Line sunitinib in patients with renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease: clinical outcome and patterns of radiological response. Fam Cancer 14 (2): 309-16, 2015.

- Stamatakis L, Shuch B, Singer EA, et al.: Phase II trial of vandetanib in Von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 31 (15 Suppl): 4584, 2013.

Also available online . Last accessed October 22, 2024. - Jonasch E, McCutcheon IE, Gombos DS, et al.: Pazopanib in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease: a single-arm, single-centre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 19 (10): 1351-1359, 2018.

- Dahr SS, Cusick M, Rodriguez-Coleman H, et al.: Intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor therapy with pegaptanib for advanced von Hippel-Lindau disease of the retina. Retina 27 (2): 150-8, 2007.

- Kondo K, Kim WY, Lechpammer M, et al.: Inhibition of HIF2alpha is sufficient to suppress pVHL-defective tumor growth. PLoS Biol 1 (3): E83, 2003.

- Courtney KD, Infante JR, Lam ET, et al.: Phase I Dose-Escalation Trial of PT2385, a First-in-Class Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-2α Antagonist in Patients With Previously Treated Advanced Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 36 (9): 867-874, 2018.

- Jonasch E, Donskov F, Iliopoulos O, et al.: Belzutifan for Renal Cell Carcinoma in von Hippel-Lindau Disease. N Engl J Med 385 (22): 2036-2046, 2021.

- Frantzen C, Kruizinga RC, van Asselt SJ, et al.: Pregnancy-related hemangioblastoma progression and complications in von Hippel-Lindau disease. Neurology 79 (8): 793-6, 2012.

- Ye DY, Bakhtian KD, Asthagiri AR, et al.: Effect of pregnancy on hemangioblastoma development and progression in von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Neurosurg 117 (5): 818-24, 2012.

Prognosis

Historically, patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) had poor survival when compared with the general population, because of the morbidity and mortality of the various disease manifestations and the resultant management.[

In the past, metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) has caused about one-third of deaths in patients with VHL and, in some reports, it was the leading cause of death in VHL patients.[

Morbidity and mortality in VHL vary and are influenced by the individual and the family's VHL phenotype (e.g., type 1, 2A, 2B, or 2C). For more information, see the

References:

- Maher ER, Yates JR, Harries R, et al.: Clinical features and natural history of von Hippel-Lindau disease. Q J Med 77 (283): 1151-63, 1990.

- Binderup ML, Jensen AM, Budtz-Jørgensen E, et al.: Survival and causes of death in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Med Genet 54 (1): 11-18, 2017.

- Wang JY, Peng SH, Li T, et al.: Risk factors for survival in patients with von Hippel-Lindau disease. J Med Genet 55 (5): 322-328, 2018.

- Lamiell JM, Salazar FG, Hsia YE: von Hippel-Lindau disease affecting 43 members of a single kindred. Medicine (Baltimore) 68 (1): 1-29, 1989.

- Horton WA, Wong V, Eldridge R: Von Hippel-Lindau disease: clinical and pathological manifestations in nine families with 50 affected members. Arch Intern Med 136 (7): 769-77, 1976.

- Neumann HP: Basic criteria for clinical diagnosis and genetic counselling in von Hippel-Lindau syndrome. Vasa 16 (3): 220-6, 1987.

Future Directions

Currently, the renal manifestations of von Hippel-Lindau disease (VHL) are generally managed surgically or with thermal ablation. There is a clear need for better management strategies and development of targeted systemic therapy. These will include defining the molecular biology and genetics of kidney cancer formation, which may lead to the development of effective prevention or early intervention therapies. In addition, the evolving understanding of the molecular biology of established kidney cancers may provide opportunities to phenotypically normalize the cancer by modulating residual VHLgene function, identifying new targets for treatment, and discovering synthetic lethal strategies that can effectively eradicate renal cell carcinoma.

Latest Updates to This Summary (10 / 23 / 2024)

The PDQ cancer information summaries are reviewed regularly and updated as new information becomes available. This section describes the latest changes made to this summary as of the date above.

Added

Revised

Added

This summary is written and maintained by the

About This PDQ Summary

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary for health professionals provides comprehensive, peer-reviewed, evidence-based information about the genetics of von Hippel-Lindau disease. It is intended as a resource to inform and assist clinicians in the care of their patients. It does not provide formal guidelines or recommendations for making health care decisions.

Reviewers and Updates

This summary is reviewed regularly and updated as necessary by the

Board members review recently published articles each month to determine whether an article should:

- be discussed at a meeting,

- be cited with text, or

- replace or update an existing article that is already cited.

Changes to the summaries are made through a consensus process in which Board members evaluate the strength of the evidence in the published articles and determine how the article should be included in the summary.

The lead reviewers for Von Hippel-Lindau Disease are:

- Alexandra Perez Lebensohn, MS, CGC (National Cancer Institute)

- Brian Matthew Shuch, MD (UCLA Health)

- Ramaprasad Srinivasan, MD, PhD (National Cancer Institute)

Any comments or questions about the summary content should be submitted to Cancer.gov through the NCI website's

Levels of Evidence

Some of the reference citations in this summary are accompanied by a level-of-evidence designation. These designations are intended to help readers assess the strength of the evidence supporting the use of specific interventions or approaches. The PDQ Cancer Genetics Editorial Board uses a

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. Although the content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text, it cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless it is presented in its entirety and is regularly updated. However, an author would be permitted to write a sentence such as "NCI's PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks succinctly: [include excerpt from the summary]."

The preferred citation for this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Cancer Genetics Editorial Board. PDQ Von Hippel-Lindau Disease. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at:

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use within the PDQ summaries only. Permission to use images outside the context of PDQ information must be obtained from the owner(s) and cannot be granted by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the illustrations in this summary, along with many other cancer-related images, is available in

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used as a basis for insurance reimbursement determinations. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our

Last Revised: 2024-10-23

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Ignite Healthwise, LLC, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the

Healthwise, Healthwise for every health decision, and the Healthwise logo are trademarks of Ignite Healthwise, LLC.

Page Footer

I want to...

Audiences

Secure Member Sites